From ‘Native Studies Review’, 1992

This report is the product of a conference on the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples that I attended at Ottawa in May 1992. Delegates were asked for input on matters of research for the Committee. My report includes not only research issues, but ideas and thoughts related to the Constitution, colonization, self-government and the role of Aboriginal women. My input to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples is based partly on my experience as an Aboriginal person from a rural ghetto and partly on my ideas developed as a professor in university Native Studies programs. My report does not take the typical point of view, where Indians and Métis, and their communities, are regarded as the “problem,” that research should focus on attempted solutions to transform them from their ghettos and reserves to a mainstream market system. I believe it is the state, its institutions and structures that are at fault for the oppressive and deprived conditions of Aboriginal people. Canada is similar to all other countries that were conquered and dispossessed by Western European imperialism in the 16th and 17th centuries. It is a quasi-apartheid, colonized nation. Therefore, it is the state, its institutions and structures that should be researched for their oppressive and discriminatory practices and governance over the Indians and Métis. We are critically colonized and subjugated people, and have been for the last 450 years. Our problem is the struggle for liberation.

Throughout the lengthy negotiations on the Constitution, I did not feel that they were relevant or meaningful to the rank and file of Aboriginal people. For these people it was an unknown and unheard-of matter. It involved only a few elite comprador leaders and their organizations; namely, the Native Council of Canada, the Métis National Council, the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada and the Assembly of First Nations. In most cases, constitutional negotiations are ruling-class constructions. This was the case for the Charlottetown Accord.

From my experience in speaking at remote Métis and Indian communities. I learned that these distant people had absolutely no knowledge about the Constitution and the negotiations. Consequently, they had no concern or involvement whatsoever. Hence, the immense discussions on Aboriginals and the Constitution as reported daily to Canadian living rooms was largely a media event. Nevertheless, many Native people were concerned about the issue of self-government. Métis and Indians were brought into the constitutional accord as a result of their political awakening in the civil rights struggles of the 1960s and 1970s. “Since the 1960’s, however, there has been a remarkable awakening. Today Indian (and Métis) culture is seen as vital to community pride and self-reliance… provincial and national organizations are asserting Indian claims to land resources, treaty rights and self-government.” (1) This awakening caused international embarrassment to the governments and politicians. Mass media coverage on the Constitution provided an opportunity for the federal government to improve its so-called human rights concerns for Aboriginal people.

Negotiations on the Constitution also helped to take the focus off the threat of Quebec secession. “Canada’s Aboriginal people are front and centre in the debate over the constitution… [T]heir demands for constitutional recognition, self-government and land claims played a major role in blocking changes that would have allowed Quebec to sign the constitution.” (2) During the constitutional talks, Aboriginal people, including the leaders involved, did not really understand what was transpiring. It was continuous confusion and vagueness, due to the lack of clarity in terminology and concepts such as self-government. It is little wonder that the remote and poorly educated did not know what was being negotiated. To many Indians and Métis constitutional talks were staged media events by the four Aboriginal organizations. There should have been greater participation by the masses. From such exercise, Indigenous ideas and perspectives would have emerged and contributed towards reaching an authentic agreement.

Historically speaking, however, constitutions were primarily creations of Western European countries in the late 18th century that established nation-states to safeguard their capitalist economies. Constitutional colonization is a long process of dispossession of Aboriginal people, their land and resources through a proliferation of treaties, charters, proclamations, acts, etc. They are intentionally designed to serve the interests of the colonizing bourgeoisie at the expense of the oppressed Aboriginals. They represent judicial, parliamentary and bureaucratic authoritarianism over the Indigenous people of that territory. In Canada the Constitution is a product of industrial capitalism and its framers in the early 1800s. The British North America Act of 1867 reflects that structure and intentions. The major reason that the Constitution became an issue for change was because Canada had moved to post-industrial society, and the new global corporate class wanted it brought into line with their current needs.

The Aboriginal elites supported the Charlottetown Accord, claiming that it was a step forward; that their land claims would not be eroded; that they would become one of the three equal orders of the government of Canada. But many Aboriginal people believed that placing Native rights under someone else’s constitution would be a surrender of sovereignty and would terminate all treaties. The Métis, Inuit and Indians would not be handed powers, but instead a list of goals, such as the protection of language, culture and tradition. How they protected these, and what powers they needed to do so, would be worked out later. However, Chief Mercredi, the Assembly of First Nations and its 550 band-council chiefs apparently stood to gain control of five billion dollars from Indian Affairs funding at the expense of treaties and Native rights. (3)

Self-Government

The concept of self-government, as far as I was concerned, was much too vague and manipulative to be used in the Constitution. There were no real specifics that gave it a definitive meaning. Another concept should have been used that would have included political autonomy, but not nationhood. As Aboriginal participants we should view these concepts critically as they have different meanings in different historical periods. During the early 1800s there was a strong movement in Europe towards the development of nation-states, and of course, self-government. It was to the advantage of the leaders of these national movements to establish nation-states, due largely to the progressive nature of imperialism and capitalism at that time. However, today the political and economic scene is a very different one. It is a period of global corporatism in which there is only one superpower influencing and determining many economic and political policies. It may be beneficial to global corporations that internal colonies become sovereign, which at the same time would be seriously disadvantageous to Aboriginal people who occupy them. It is well known that Indian lands contain a vast wealth of many resources. These resources are the crux of constitutional negotiations and the push for Indigenous self-government. We must be cautious. Colonialism today has become technologically perfected and immensely versatile. The metropolis can exploit effectively and rapidly its internal colonies (i.e., reserves and Métis colonies).

I am questioning whether this is a time in history when self-government would be advantageous to Aboriginal people. I am not suggesting that we should postpone the movement towards autonomy. But I am suggesting that we should be most critical and careful in our analysis and negotiations with the government. The state’s track record is all too familiar to Aboriginal people. I believe that it is the most appropriate period in history of Indians and Métis to clearly establish self-determination that institutes possession and control of our land resources, as well as political autonomy.

The British Columbia Sechelt Indian Band form of self-government is a good example of misunderstandings of self-government. Although much praise is given by government officials and the media to this band for achieving self-government, many Indians regard it as a “sell out” in which the Sechelt Indians received very little for surrendering much of the land. This case reveals the problems in understanding self-government. To many people, it is nothing more than the administration of local council matters. The council has no autonomy. Instead there is “constitutional entrenchment of the power of the Province and the role of the Indian agent in managing reserve lands.” Under these conditions, self-government means a loss of land claims, and an entrenchment of colonization. In my assessment, self-government does not constitute any change for Aboriginal people in terms of autonomy or sovereignty. Although it may be given extensive consideration in terms of rhetoric, in the end it is still colonialism.

A group of concerned band members complained that “We got rid of the Indian Act, but took the Indian Agent with us. The Band Council… are good at dealing with everything, but the aboriginal people.” (4)

Self-government as a concept does not serve the goals of Aboriginal people. It is inadequate as a term for constitutional negotiations. Richard Bartlett gives a thorough and explicit interpretation on self-government from different perspectives: legal, historical and with regard to land claims. He states that “Canada assumed jurisdiction upon conquest and settlement and subjugated the aboriginal peoples, land and resources.” The federal and provincial governments relied on their powers as distributed under the Constitution Act of 1867. According to Bartlett, “they conferred exclusive jurisdiction upon the Federal Government in relation to Indians and lands reserved for Indians. The Federal government exercised that authority to subjugate Indian peoples, lands and their resources.” (5) Self-government for the federal government means full power to administer Aboriginal lands and resources.

Although the colonizer refers only to Indians, he makes no distinction between the various groups of Native people. Therefore, Métis and Inuit are included when the colonizer speaks of Indians. It is only the specifics that are different. Frantz Fanon claims that the colonizer leaves the form and appearance of traditional government, but that he empties it of all power and substance. This is quite evident in band councils and Métis community councils. “The Government-in-Council,” notes Bartlett, “may at any time withdraw from a band a right conferred upon the band.” (6) Under self-government, the federal and provincial governments retain control of all resources on the lands of Aboriginal people.

In 1944, the Saskatchewan government set aside 92,000 acres of land at the Green Lake region under the governance of the Department of Municipal Affairs with the view to providing Métis with permanent homes and the opportunity of earning a livelihood. No statuary provisions were made for local Métis government. In fact, the farm was controlled authoritatively by a White overseer. Métis workers did the manual, seasonal and menial jobs. They had absolutely no voice in the administration of this land settlement. In 1989 Premier Grant Devine privatized these farms, animals and machinery and sold all to a businessman in Prince Albert without even consulting the Métis people at Green Lake. Is it any wonder that the Métis people of northern Saskatchewan are disillusioned and suspicious of government in any and all negotiations?

The state, including the government, the police, the courts and the church, uses a variety of methods, depending on current events, to maintain the status quo and control Indigenous people. During the 1960s, when Canada’s Indigenous people began to move in much greater numbers to the urban centres, the Canadian government became increasingly concerned about racial unrest. Until that time, Canada’s Aboriginal population had remained within the precise structures of the state, where they were easily controlled by bureaucratic procedures. The Natives’ considerable exodus from the reserves, however, and their growing sense of nationalism and political consciousness, forced the state to reform its colonial administration, alter its strategies and usher Canada into a period of neocolonialism. To the public, it appeared that the government was steering away from colonial management and guiding the Natives to pseudo-independence. In reality, neocolonialism is strictly a change in how the state controls the colonized; it does not represent a step forward towards true Aboriginal self-determination.

Instead neo-colonialism means the state seeks to control Indigenous people with collaborators from their own group who use more direct and brutal methods with greater suppression. Neo-colonialism, like the earlier forms of oppression, has everything to do with racism, class and the manipulation of resources and money to censor and shape Aboriginal thought. Neo-colonialism, based on this foundation, is merely a more sophisticated form of colonial administration. Rather than bussing Natives to sugar beet fields against their will, the state implemented job training programs and controlled them through funding.

Poorly funded so-called economic development programs designed to develop small business enterprises, such as service stations, trucking and grocery stores, were another outgrowth of Canadian neo-colonialism. In northern Saskatchewan, for example, the government provided loans to Native people who wished to set up small trucking firms to serve the uranium mines. Again, the government’s objective was to secure a steady supply of cheap labour – the idea being that Native workers would be more willing to work for low wages if they were working for a Native. The second objective was to induct a select group of Natives into the petty bourgeois class, imprisoning their consciousness and identity.

The state also used its funding to attack local Native political organizations and obstruct the Natives’ movement for liberation and self-determination. Beginning in 1971, the Secretary of State provided large grants to provincial Native organizations in order to co-opt them. Once autonomous, these organizations and their elected leaders were provided with huge salaries and funding. Besides creating a captive leadership, the state determined what the organization did by the kind of grants it provided. Instead of representing their people politically, as was originally intended, Native organizations gradually took on more and more of the responsibilities and services that the government was supposed to provide. In addition, the service programs merely dealt with the symptoms, not the underlying causes of oppression, poverty and political inequality.

Racism and colonial struggles were the fundamental issues uniting and motivating Native people during the early stages of the civil rights movement. Aboriginal people were struggling to develop a sense of pride in their heritage and nationalism. Part of their identity was firmly rooted in their recognition that economic issues are linked politically to liberations. Sensitized to the politics of unequal class power and privilege, many Native activists promoted a philosophy of self-determination as the key to social and economic liberty. To counter the grass-roots movement of Native radical nationalism, governments at the federal and provincial levels from 1972 onward promoted Native cultural imperialism, based on the traditional and spiritual components of Indigenous culture. Cultural imperialism reinforces a caricatured image of Native culture. Its purpose is to revive primitive folkways, contrived traditionalism and archaic activities and ceremonies; thus steering Native people away from political activities to participate instead in state-funded ceremonies such as “Back to Batoche.” With their substantial financial reserves, the state succeeded in overshadowing and eventually obliterating the Natives’struggle for a progressive political and economic development.

Another successful and efficient strategy the state employed to quash the Natives’ liberation struggle was dividing Canada’s Indigenous population into different tribal and ethnic groups. At the outset of the civil rights movement, Indigenous people worked together as a united force. In response to this formidable challenge, the government scrambled to create friction among its enemies by separating Natives into Non-Status, Métis and Status Indians. The state sought to foster suspicion and jealously by using classifications to justify unequal distributions of funding, programs and land claim settlements. In the Third World this tactic has led to tribal warfare. In Canada, this policy still continues, dividing and subdividing Indigenous people. As late as 1987, the Secretary of State granted $60,000 to stage a referendum in Saskatchewan that led to the official separation of the Metis from non-Status Indians. This is a useless and dangerous exercise that serves only the state’s purpose.

The state’s other strategies included establishing education and training centres in towns and cities that had large Native populations, where they “reached out” to displace Natives in order to socialize them to the capitalistic ethic, emphasize cultural nationalism and stall political activities. Those Aboriginals who received benefits simply developed a greater dependency on the state and their political consciousness became neutralized. Ultimately, the state was only interested in perpetuating Native’s dependency by promoting underdevelopment and economic irresponsibility and by smothering responsible leadership. By forming a petite bourgeois Indigenous class that was closely allied to and dependent on the state, it was able to diffuse the Natives’ protest movement. Likewise, the Aboriginal government employees removed themselves from their Native communities and the liberation struggle and became socialized into a conservative ideology and urban lifestyle. They saw themselves as important state bureaucrats, but in reality they were merely puppets. They took a collective stand against the liberation struggle. The state had succeeded in dividing the Aboriginal people, and maintaining them within the structure of colonization.

The Role of Aboriginal Women

Aboriginal women may not have played a major role in the Charlottetown Accord, but they had a significant impact on the consequences of the overall constitutional negotiations. The family has been very traditional in Aboriginal society. The husband was the provider, protector and decision-maker. Women were the conventional wife, mother and care-taker of children. They helped their husbands with outside tasks when necessary. Since many Aboriginal families were Catholics, they lived in a highly patriarchal system. Men were the dominant decision-makers within the home. However, this power rarely extended beyond the home. Social status in this realm was very limited. Among the colonized, self-esteem is very low and restricted. This colonizing process serves to enslave Native people, chaining them to an inferior rank. As a result, many Indigenous males revolt against those persons closest to them – their family members. It is the result of attempting to preserve one’s ego.

However, Aboriginal women eventually refused to accept this abusive and subservient role, and have now organized to achieve equality with Aboriginal men. The current struggle of the Aboriginal Women’s Unity Coalition against the leadership of the Assembly of First Nations over funding and over the Social Charter is a highly commendable effort. In their protest against the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, the women argued that, “Not only are we the victims of violence at the hands of Aboriginal men, our voice as women is not valued in the male dominated political structures. We have found it necessary to speak out against the violence and the sexism within our community even though it means breaking ranks with the Chiefs.” (7)

The Aboriginal Women’s Unity Coalition of Winnipeg complain about the abuse of power by elected chiefs and councillors that is reflected in bloc voting by families and preferential hiring of relatives of the chief. Problems of abuse of power are traced directly to the chief/council system that has been imposed by the federal Indian Act. These are not fortuitous political situations. They are integral parts of colonization. It is policy with governments that the traditional family arrangement be preserved. But, in making this policy, they keep wives and mothers colonized and subordinated. White male bureaucrats are reluctant to deal with Aboriginal women as leaders and decision makers.

Gail Stacey-Moore, President of the Native Women’s Association of Canada, is justified in seeking the same federal recognition and support given recently to four male-dominated Aboriginal groups. There is a need for a women’s group to have its own voice to fight for retention of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms under self-government. The Women’s Association also argues that “the national and local aboriginal leadership is male-dominated and isn’t sensitive to women’s needs.” (8) Most of the Aboriginal organizations were created or revived as a result of the civil rights struggle in the 1960s, which was guilty of male structure and dominance. They have changed only slightly in the past thirty years. Unless Aboriginal women exert pressure, these outdated organizations will persist. The governments support and fund them. Even if the Women’s Association should cause a disruption or disunity among the Aboriginal population, it is much better that we resolve our internal conflicts and create an authentic democracy now. Attempting to mask from the media our internal conflicts only promotes further inequality, injustice and male domination.

Aboriginal women and their organization were denied a place at the negotiating table. They launched a federal court action demanding a seat at the constitutional talks and as much as $2.5 million – the same support given to four male-dominated Aboriginal groups. The federal court of appeal agreed and ruled that the Native women were wrongly denied a place at the negotiating table. (9) The women claimed that “their exclusion has had a very negative effect.” President Stacey-Moore stated that “the four male national Native organizations… [have] continued to refuse to let the group participate in the continuing talks.” (10) Aboriginal women objected to a clause that would let Aboriginal governments exempt laws from the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

However, in the final outcome, Native women and their organization were excluded from the Charlottetown Accord negotiations. These actions proved that the Canadian corporate power is still dominant and that Indian and Métis women are absolutely subjugated to these colonial and sexist structures. It seems apparent that their liberation will not be achieved through peaceful negotiations at the conference table. Other, more forceful, measures will have to be taken.

Conclusion

The Charlottetown Accord revealed two important consequences for Aboriginal people. First, though temporarily defeated, the women have awakened and emerged as the new power group in our society. There is every likelihood that they will overturn male dominance and supersede them as the new political force. Second, formal Aboriginal organizations were exposed as being irrelevant and meaningless to the Aboriginal population. They have been revealed as being merely puppet and collaborator leaders and organizations. It was clearly shown that they have little or no influence with the people of Indian reserves and Métis colonies. They are totally ineffectual as representatives for the Aboriginal masses. As a result, they are useless and unessential to their colonial masters in Ottawa. The fall-out from the Charlottetown Accord will bring almost immediately new arrangements in political power groupings and different approaches towards self-determination. The governments have lost much of their credibility with the Aboriginal people.

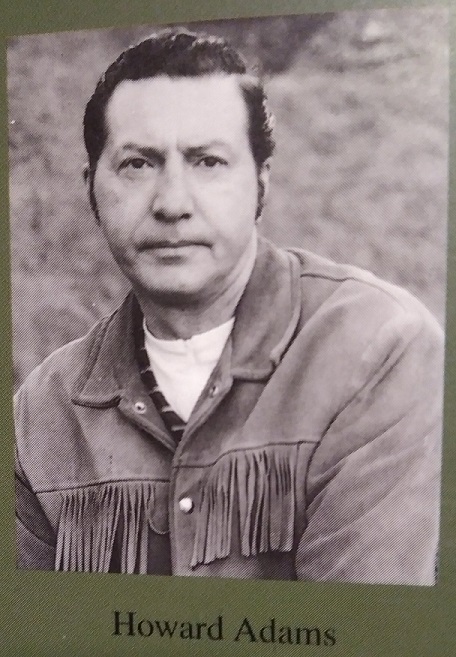

Howard Adams (Métis)

Notes

1 Vancouver Sun , 25 October 1991.

2 Ibid., p. 5.

3 Ibid., p. 8

4 Vancouver Sun, 25 Sept. 1992.

5 R. Bartlett, Aboriginal Peoples and Constitutional Reform (Kingston, Ont.:

Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, Queen’s University, 1986), p. 3.

6 Ibid., p. 13.

7 Canadian Dimensions, March 1992, p. 6.

8 Vancouver Sun, 19 March 1992.

9 Globe and Mail, 19 Sept. 1992.

10 Vancouver Sun, 18 Sept. 1992.

Also

Native Alliance for Red Power – Eight Point Program (1969)

The Native Elite, by Howard Adams (1970)

The Need for a Revolutionary Struggle, by Howard Adams (1972)

The Form of the Struggle For Liberation, by Howard Adams (1975)

‘Marxism and Native Americans’, reviewed by Howard Adams (1984)

No Surrender – Howard Adams on the Oka Crisis (1990)

Overshadowed National Liberation Wars, by Howard Adams (1992)