by M.Gouldhawke (Métis-Cree)

Updated: April 18, 2020 (Originally published December 29, 2019)

From its humble beginnings in social media memes, to its stepping out into the streets as graffiti, and now even gracing the halls of academia, Land Back is truly a slogan whose time has come. A modern solution to a modern problem. How to boil down Indigenous sovereignty and liberation to its basic components. Memes, graffiti and tweets benefit from brevity. But the term Land Back, like everything else, has a certain ancestry.

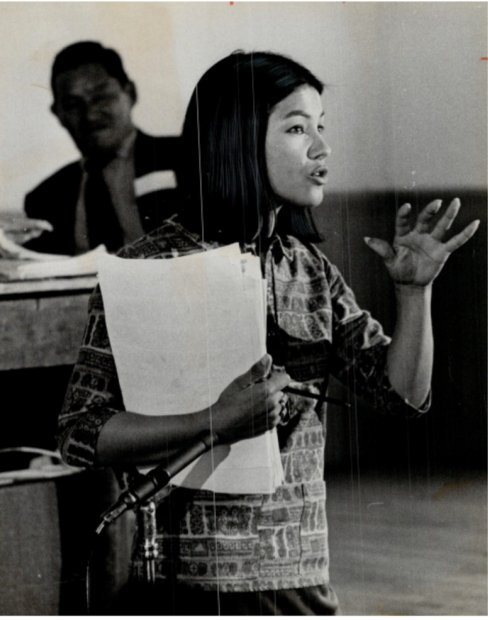

This lineage is to a significant extent matrilineal, since women have often taken prominent roles of leadership in both Indigenous cultures and modern social movements for land reclamation.

Commenting on the women who took the foreground of the 1960s Coast Salish “fish-in” struggle in the Puget Sound area, writer Lee Maracle later explained, “They were traditionalists, so there was nothing unusual about women acting as spokesmen for the group.”

“In fact,” Maracle wrote, “they told me they were having trouble getting the men involved,” a dynamic echoed decades later by the Haudenosaunee/Mohawk women who organized and led land defense actions at Kanehsatake in 1990 and Kanonhstaton in 2006.

Dakota writer Vine Deloria Jr, in his 1974 book, “Behind the Trail of Broken Treaties,” identified the Haudenosaunee Confederacy’s land struggles of the 1950s and the Coast Salish fish-in movement of the early 60s as launching a new kind of tactic, one that would later gain the spotlight at Alcatraz, the Trail of Broken Treaties and Wounded Knee. But he also clarified that this type of action had a history and context. It didn’t spring out of nowhere.

In his book, Deloria gave a brief but important overview of both the legal and extra-legal confrontations between various Indigenous nations and the United States (US) government that led up to the increasingly direct action focused movement of 1950s and 60s.

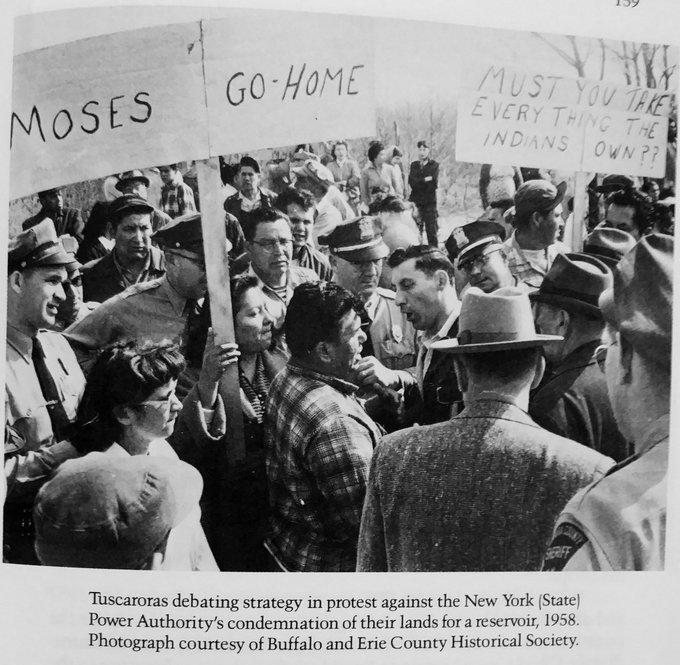

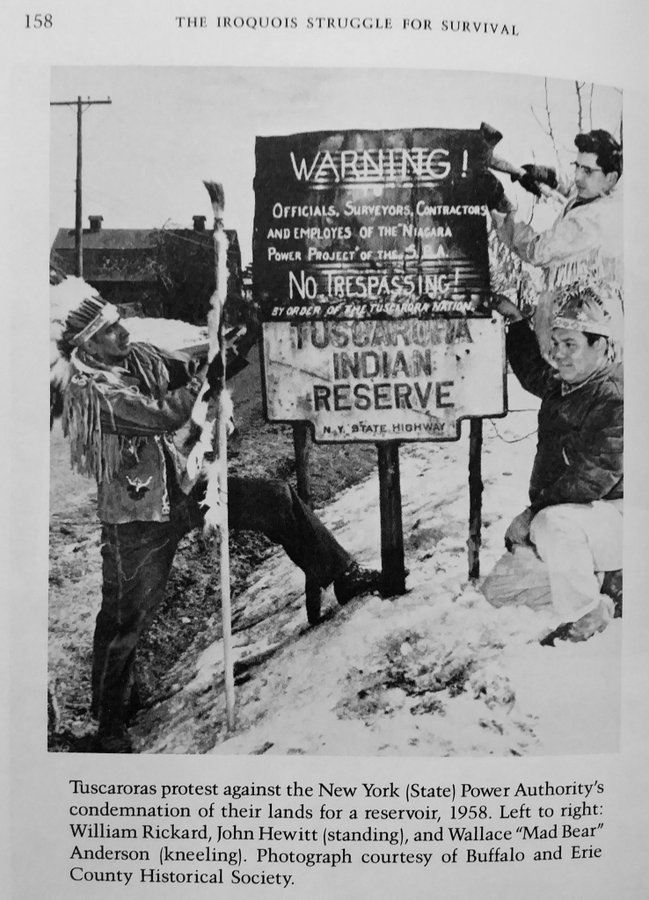

Similarly, Laurence M. Hauptman’s 1986 book, “The Iroquois Struggle for Survival,” documents demonstrations and legal challenges against assimilation and government development projects by various Haudenosaunee communities going back to the 1930s.

“The modern Indian movement for national recognition,” explained Deloria in his book, “has its roots in the tireless resistance of generations of unknown Indians who have refused to melt into the homogeneity of American life and accept American citizenship.”

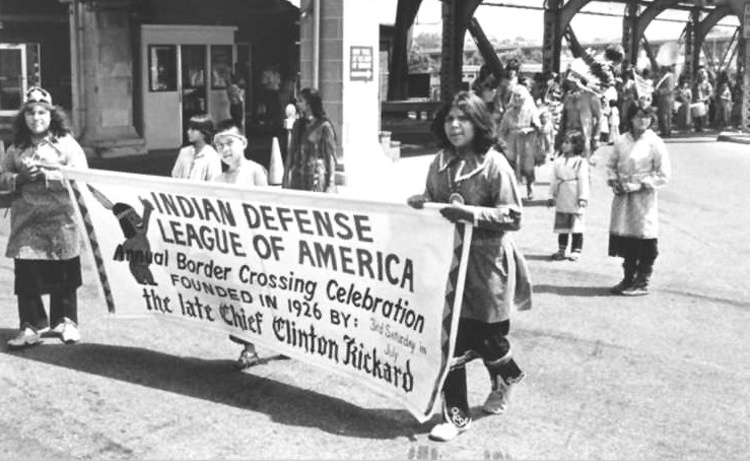

Such a refusal of both American and Canadian citizenship, and the assertion of the right to freedom of movement across colonial borders, has in fact always been an especially characteristic element of the Haudenosaunee struggle, as the Confederacy opposed the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 and began annual demonstrations in 1926 at the Niagara Falls border to uphold the Jay Treaty of 1795, which is supposed to guarantee exactly such freedom of movement for Indigenous peoples.

Throughout the 1950s, people of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy’s Allegany, Tuscarora, Grand River, Akwesasne and Kahnawake reservations in New York State, Ontario and Quebec launched a series of demonstrations, occupations of government buildings, and land re-occupations to defend their territory from government encroachment, including massive settler infrastructure development projects such as dams and reservoirs.

The construction of the Saint Lawrence Seaway as a capitalist commodity transport corridor demanded the expropriation of Mohawk land at Akwesasne and Kahnawake, spurring land defense re-occupations first at Kahnawake and then at Schoharie Creek in New York State, which lasted more than a year, ending in 1958.

In 1959, traditionalists re-occupied the council house at the Six Nations of the Grand River reserve in Ontario, which was then raided again by dozens of Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), having already been raided by the force back in 1924 to install an Indian Act band council.

In 1925, traditionalist Grand River chief Deskaheh (of the Cayuga Nation), while ill during the last days of his life, had stayed with the Rickard family at the neighboring Tuscarora reserve, across the border in New York State, and had encouraged the struggle for freedom of movement across colonial borders.

Chief Clinton Rickard, Chief David Hill Jr. and Sophie Martin formed the Indian Defense League of the Americas around this time and launched the annual border crossing demonstrations at Niagara Falls. Haudenosaunee women in this era were also active in education and fighting against residential schools (Emily C. General), pursuing land defense legal cases (Laura Kellogg, Mary Winder and Delia Waterman), and in creating literature that did not shy away from Indigenous resistance (E. Pauline Johnson).

In 1961, Karen Rickard, Chief Clinton Rickard’s daughter from the Tuscarora reserve, went on to be a founding member of the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC), the group credited with coining the slogan Red Power (a term which only has one more syllable than Land Back, showing times haven’t changed that much really.)

The struggle then shifted to the west coast, to Coast Salish territory in the Puget Sound area of Washington State, where on December 23, 1963, some of the soon-to-be founding members of the Survival of American Indians Association marched on the state capital in Olympia, carrying signs that read “No salmon – No Santa.”

This was followed by a series of fish-in actions around Puget Sound through the 1960s and 70s, attracting the support of Black activists, celebrities, and the Native Alliance for Red Power (NARP) from across the colonial border in Vancouver, British Columbia (BC), as Lee Maracle mentioned in her 1975 book, “Bobbi Lee: Indian Rebel.”

Vine Deloria Jr. made an important point in his 1974 book that the larger tribes in the Puget Sound area who had secured agreements with the State of Washington did not support the grassroots fish-in movement, but that same grassroots movement then “gave the tribal leaders some room to maneuver which they had never had before.”

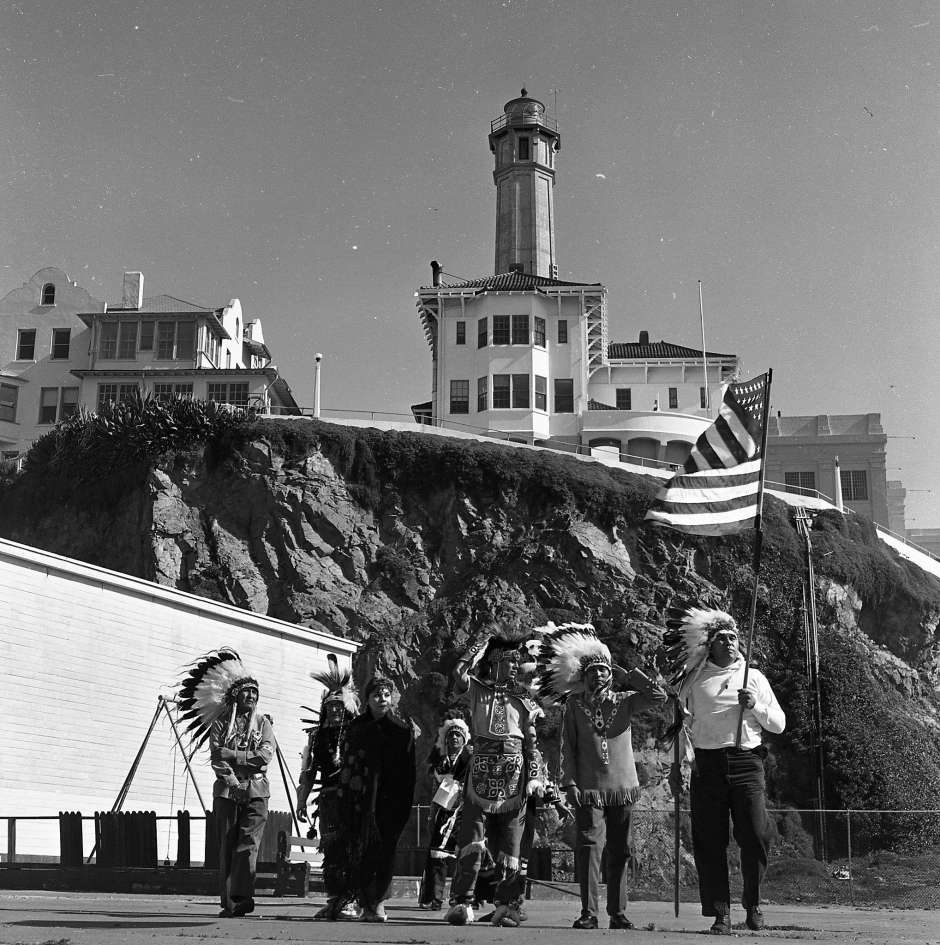

In 1964, a group of Lakota people went to Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay Area, California, and staged a demonstration citing treaty rights to reclaim the land, the same year the first Coast Salish fish-in actions took place at Frank’s Landing further north up the coast in Puget Sound.

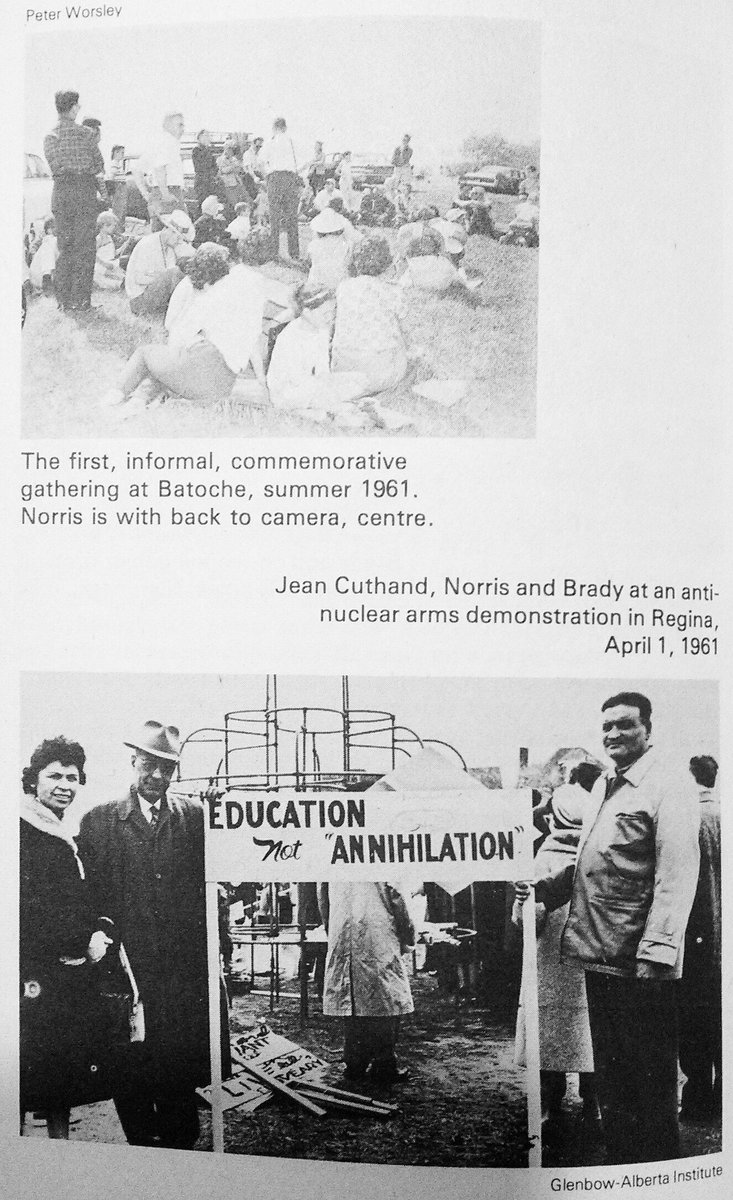

Meanwhile, on the prairies of so-called Canada, Métis socialists Jim Brady, Malcolm Norris and Mederic McDougall had been organizing since the 1930s, and their struggle would then converge with the growing Red Power movement of the 60s. Brady and Norris in fact had helped to establish the Métis Settlements of Alberta in the 30s, still the only designated land base for the Métis people in Canada or the US.

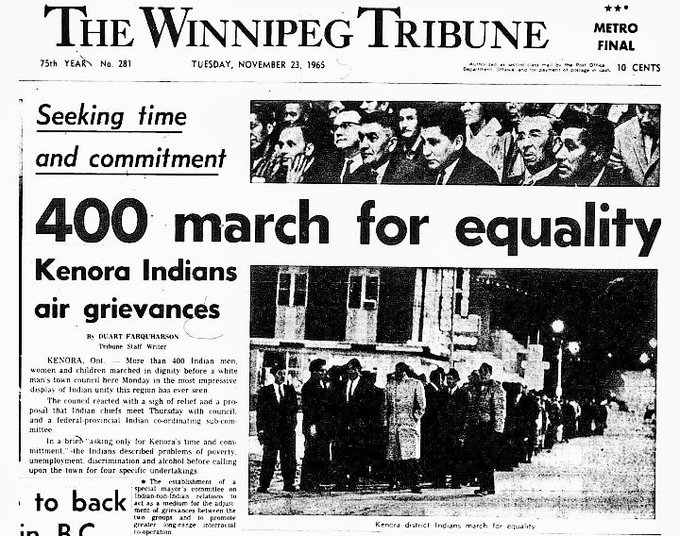

In 1965, Malcolm Norris was inspired to write an article in support of an Anishinaabe mass march in Kenora, Ontario, saying that the “Militant Action” had “done more to dramatize… the Indians’ plight than all the conferences held… in the past three years.”

Brady, Norris and McDougall also directly inspired the next generation of Métis organizers, in particular Maria Campbell and Howard Adams, whose own writing and work would in turn become a huge influence on the wider Red Power movement across Canada. In true Métis fashion, there were also direct family connections between the generations, as Maria Campbell’s father worked with and introduced her to Brady, and McDougall was an uncle of Howard Adams.

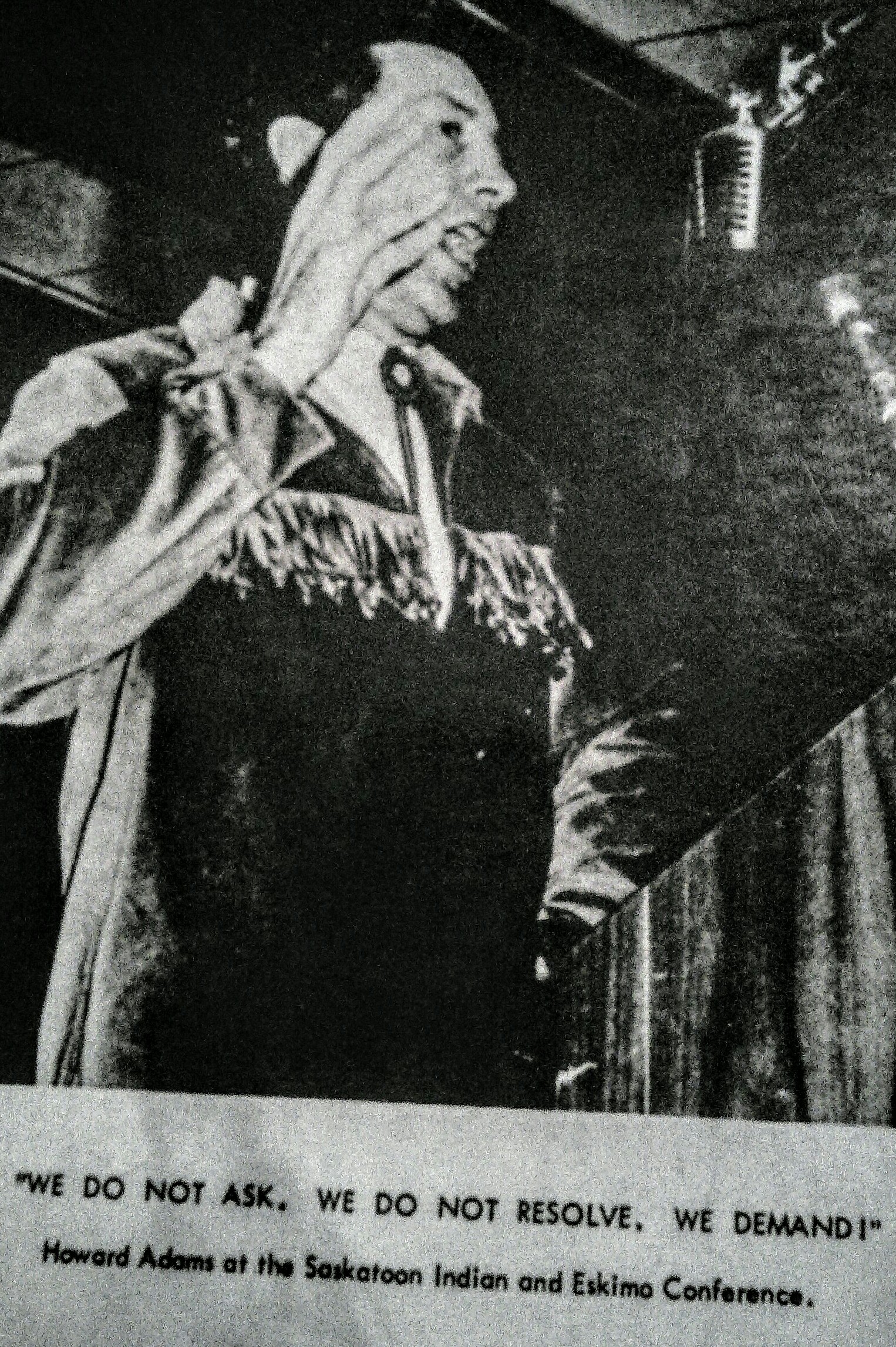

In 1967, Howard Adams told the Regina Leader-Post that “if Red Power means political power in the hands of the Indian, the movement is well under way in Saskatchewan… The movement can’t be held off. People are already talking in terms of demonstrations.”

Also in 1967, Adams chaired a Saskatoon national conference on Indian and Inuit education, which included many Indigenous women as speakers, including Kahn-Tineta Horn, already a prominent Mohawk organizer and speaker from Kahnawake (in Quebec) who spoke against Christianity in education

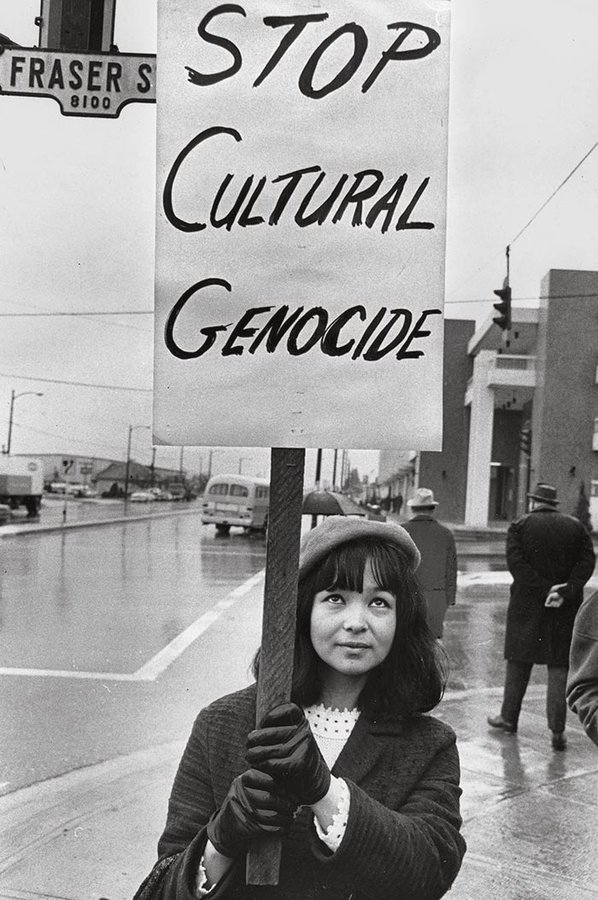

On the west coast, 1967 was the year the Native Alliance for Red Power (NARP) was founded by two Native women in Vancouver, BC. In March of 1968, the group held a demonstration against residential schools outside a school administration conference.

NARP member Lee Maracle recalled later in an interview that Howard Adams made a “tremendously inspiring” speech in 1968 on “our reserve” in North Vancouver, and that priests and nuns failed to discourage people from attending.

“There was a doctor [Adams] that was Métis. My mother’s a Métis,” said Maracle. “He’s a tremendously powerful orator. And then the distinction between writing and speaking and being a doctor and being an orator was gone… Howard was a Marxist who was going against the tide!”

“And that was wonderful,” explained Maracle, “because we all felt that there was something wrong with the Marxism in this country, and Howard defined it as the lie, the great deception, the displacement of Native people…”

In 1968, the American Indian Movement was formed in the American city of Minneapolis at a meeting called by two women and four men, with the name of the group being suggested by Alberta Downwind. Street patrols to monitor police brutality and the Heart of The Earth Survival School and Red School House in the Twin Cities soon followed, run in part by Ojibwe/Anishinaabe women like Vicki Howard, Pat Bellanger and Ona Kingbird.

In December of 1968, Mohawks at Akwesasne in Ontario, including Kahn-Tineta Horn, blocked the International Bridge and border crossing that divides their territory between the colonial states of Canada and the US.

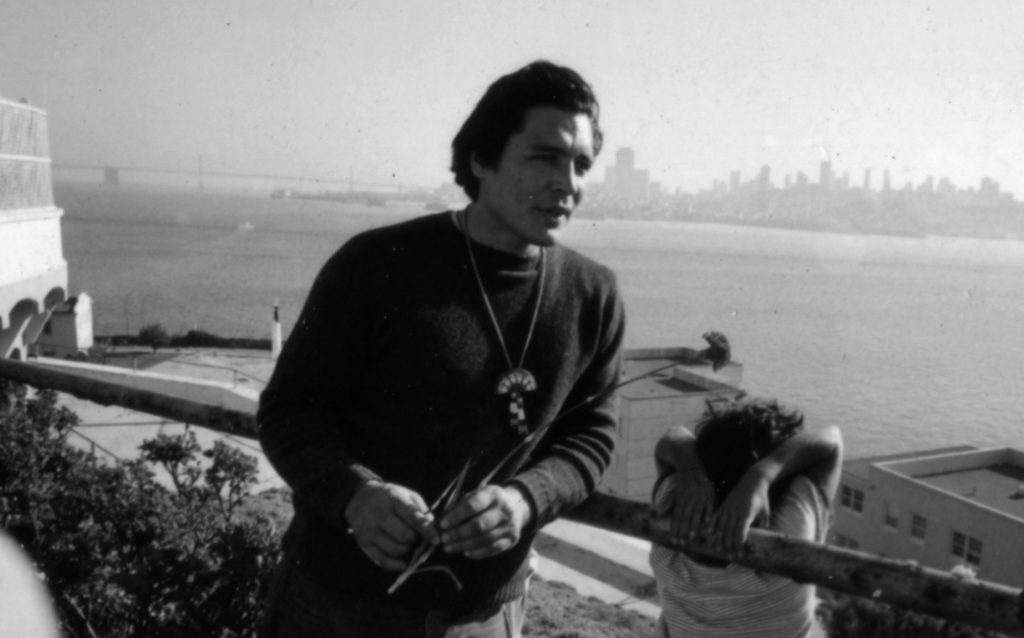

These pre-existing and already interconnected movements, the Haudenosaunee, Coast Salish, National Indian Youth Council and American Indian Movement then converged at the re-occupation of Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1969, widely popularizing the Red Power movement, and inspiring a generation of Indigenous people who had become disconnected from their people and culture.

One of the prominent organizers of the Alcatraz re-occupation was Richard Oakes, a Mohawk from Akwesasne, who had previously been involved in the land re-occupations of Mohawk territory against the construction of the Saint Lawrence Seaway.

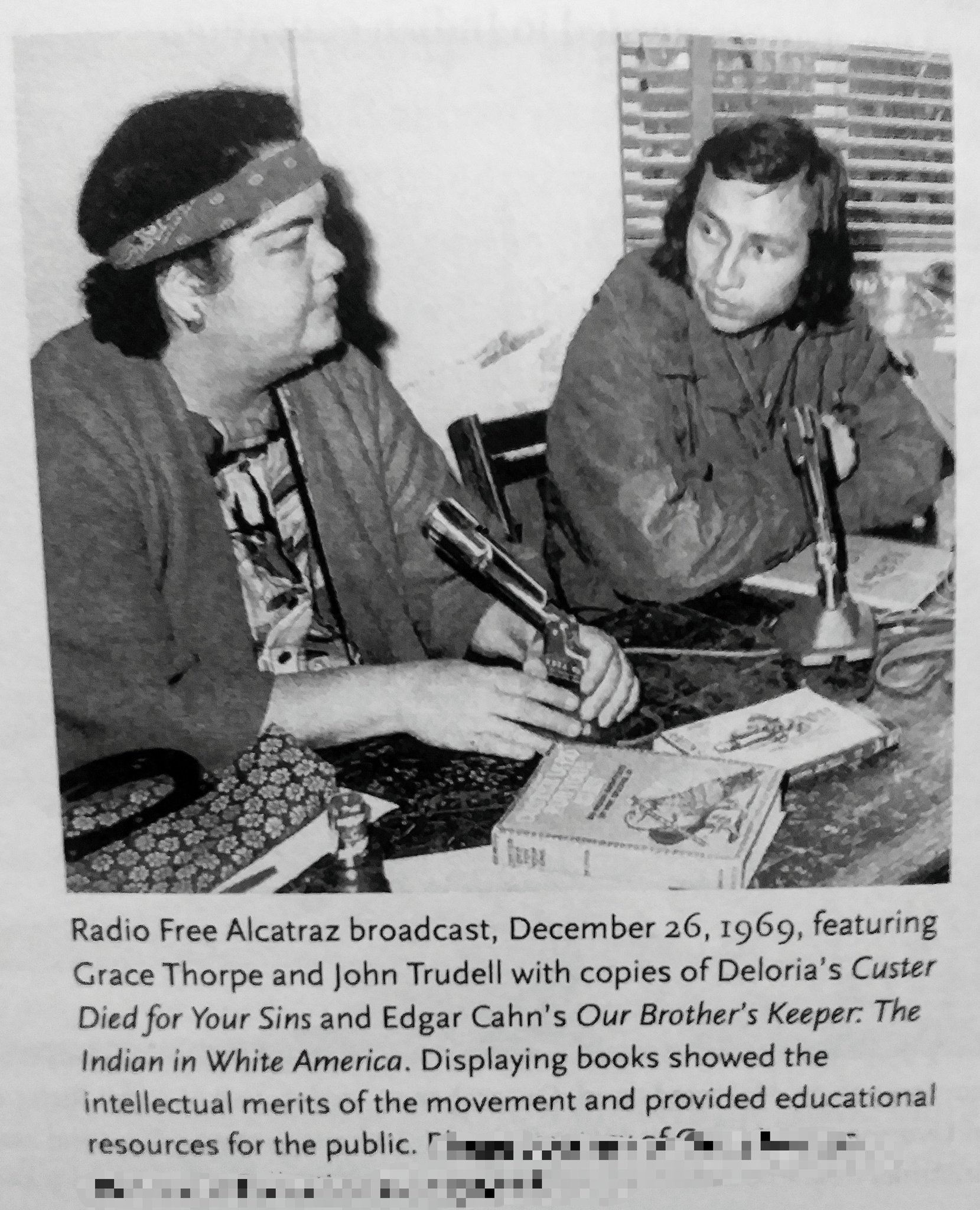

Radio Free Alcatraz began broadcasting a month into the re-occupation on December 22, 1969. Marilyn Maracle from Six Nations of the Grand River in Ontario was there and said, “I would like to see a new way of life, which is a return of the old life style in today’s terms.”

Two influential books were also released in 1969 that reflected and inspired the emerging Native politics of the time period in the US and Canada, Dakota writer Vine Deloria Jr’s “Custer Died for Your Sins,” and Cree leader Harold Cardinal’s “The Unjust Society.”

The Alcatraz re-occupation lasted a year and a half and influenced a new wave of occupations of government buildings and re-occupations of land across California and the US, culminating in the armed reclamation of Wounded Knee in 1973 at the Pine Ridge reservation of the Lakota people.

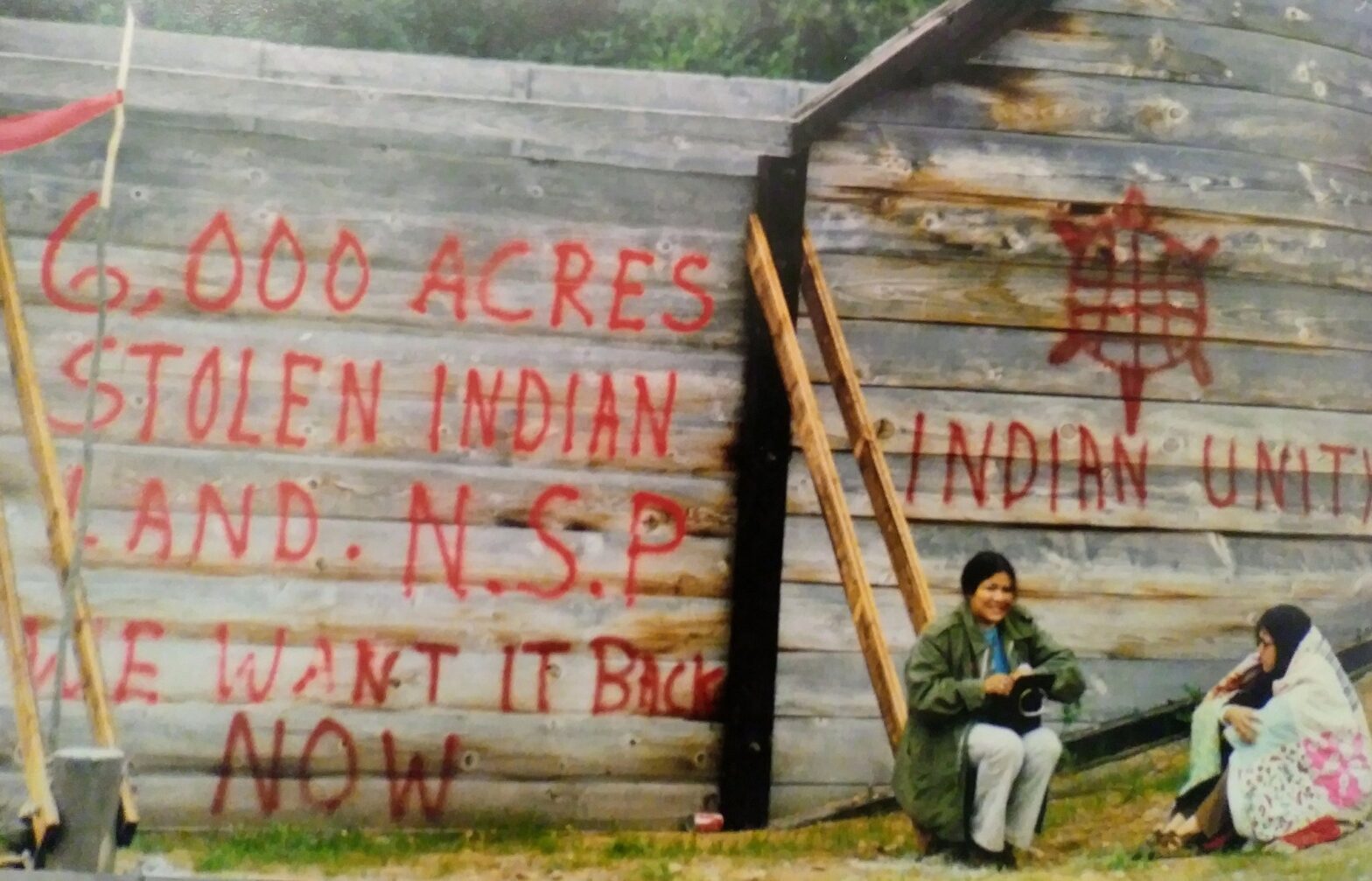

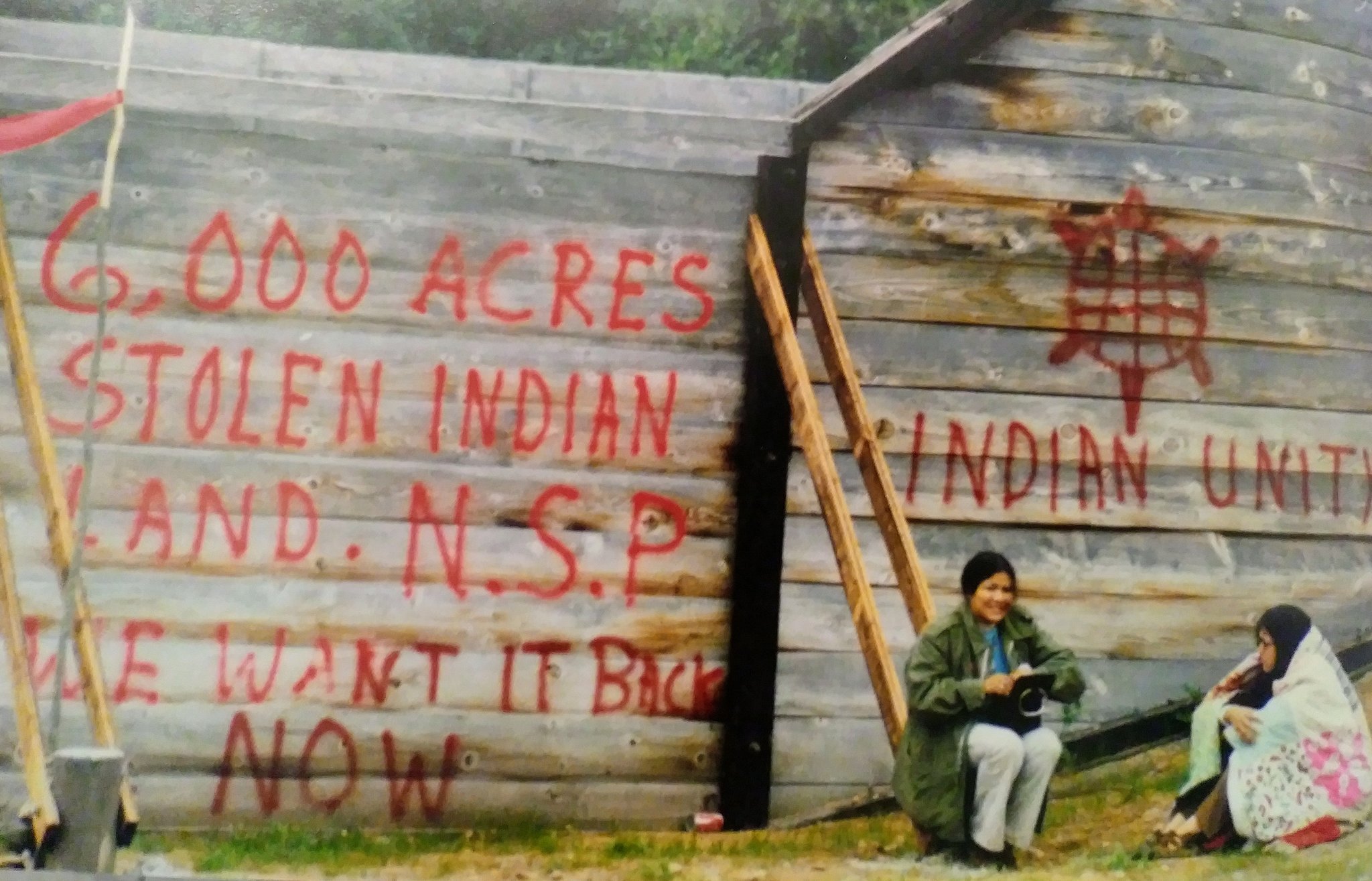

In 1970, members of the Pit River Tribe in northern California took over property claimed by the Pacific Gas and Electric Company that was repeatedly raided by police and re-occupied over the course of a few months. “Land back,” theft of water and poverty were explicitly mentioned by one of the re-occupiers as causes for the re-occupation. Another camp was set up at the “Four Corners” area and also raided by the police.

North of the border, also in 1970, Cree and Dene people took over the Blue Quills residential school in Alberta and converted it into a Native-run elementary and high school, and later a college and university which still runs today. That same year, Métis and Cree people occupied the NewStart education centre in Lac La Biche, Alberta, for 26 days and succeeded in stopping the government’s plan to cut off funding. The centre continues to operate today as “Portage College.”

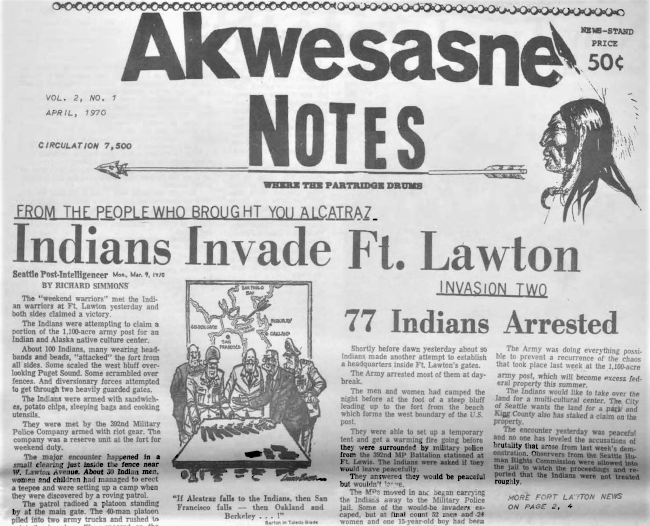

The Coast Salish struggle in the Puget Sound area continued in 1970, as traditionalists re-occupied reserve land in Tacoma and took over the military base of Fort Lawton in Seattle, resulting in dozens of arrests.

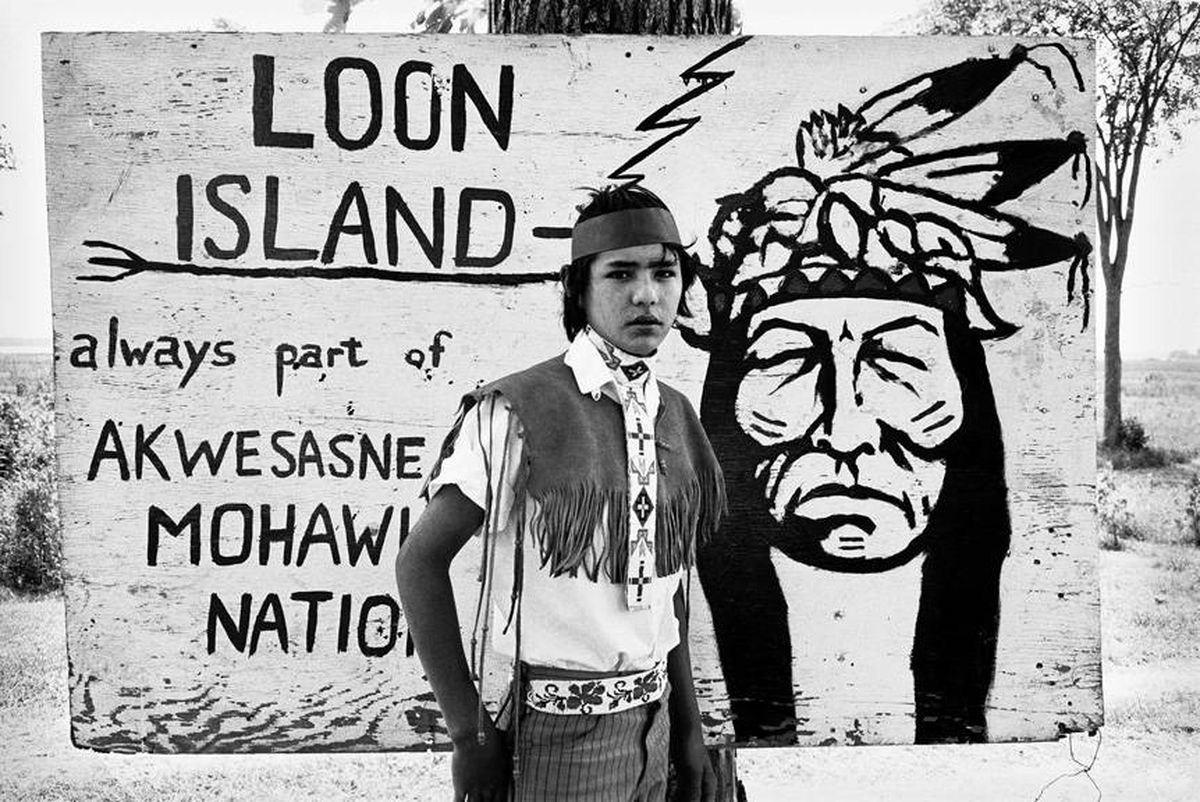

Akwesasne and Kahnawake Mohawks in 1970 reclaimed two islands in the St. Lawrence River, Stanley Island and Loon Island.

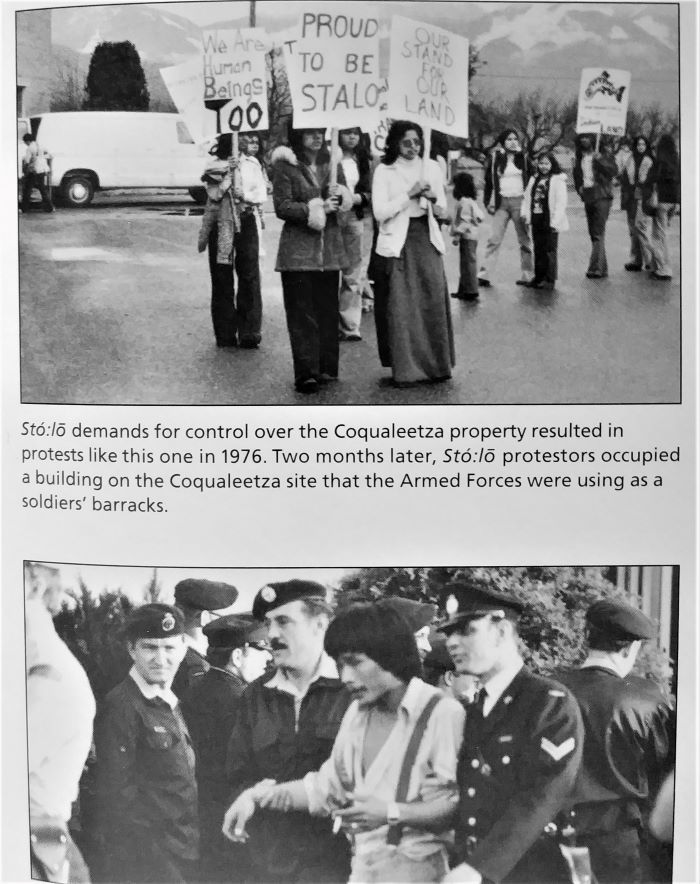

Stó:lō people in BC began a series of occupations in 1970 of the former Coqualeetza Indian Hospital that had been shut down in 1969 (also the site of a former residential school that had closed in 1940). The occupations escalated in 1976, when 26 people were arrested. In 1994, the site was converted into administration offices for the Stó:lō Nation and an “Addition to Reserve” (ATR) process remains underway.

In 1971, Mohawk warriors supported their fellow Haudenosaunee Confederacy members, the Onondaga, in their struggle against the expansion of Highway 81 near Syracuse, New York, occupying a construction site for several weeks and confronting police until compensation was secured for the Onondaga people’s loss of land.

In mid-1971, Dene and Cree people from the Cold Lake, Saddle Lake and Kehewin reserves in Alberta who were opposed to government cuts to reserve education pulled their children out of schools and started an occupation of the Indian Affairs office in Edmonton that lasted for six months, until 1972, when the Minister of Indian Affairs, Jean Chretien, finally agreed the government would provide funding to build a new school.

Métis women in Saskatoon, along with Howard Adams, launched a campaign in 1971 against the Adopt Indian Métis program run by the Saskatchewan government (the NDP at the time) which removed Indigenous children from their homes and families, often to other countries. Nora Cummings, one of those Métis organizers, spoke to the CBC podcast Finding Cleo in 2018 about the history of their struggle against the government’s program of “scooping” Indigenous children.

Métis academic and writer Allyson Stevenson in 2017 wrote an article on the same subject for the Active History site, as well as an article in 2019 detailing the history of the Saskatchewan Indian Women’s Association in the 1970s. Indigenous women in fact have always been making the connection between theft of land, theft of Indigenous children and settler violence against Indigenous women and girls.

In 1973, Kahnawake Mohawk Warriors engaged in a confrontation with the Quebec provincial police after white settlers were evicted from houses on the reserve. Police patrol cars were flipped over and armed women warriors took part in the conflict.

Mohawks re-occupied territory in New York State in 1974, declaring that at Ganienkeh (Land of the Flint) “instead of the people competing with each other, they shall help and cooperate with each other.”

In 1974, grassroots Indigenous people from across Canada organized the Native Peoples Caravan from Vancouver to Ottawa, partly inspired by the Trail of Broken Treaties in thhttps://mgouldhawke.wordpress.com/2019/11/10/when-people-are-calling-you-go-an-indigenous-womans-account-of-te US, but also in the context of armed re-occupations in Canada at Cache Creek and Anicinabe Park earlier that same year. The caravan resulted in an RCMP attack on the crowd outside the parliament buildings, but also the occupation of an abandoned mill building and its temporary conversion into a “Native Peoples Embassy.” Maria Campbell spoke at a demonstration during the Toronto stop of the caravan, saying “There are all sorts of movements happening in Canada — with women, with poor people — but today Native people are leading the struggle.”

The Indigenous resistance movement in Canada would only escalate through the 1980s, 90s and 2000s, with land (and water) reclamations such as those at Oka (Kanehsatake), Ipperwash (Aazhoodena), Gustafsen Lake (Ts’Peten), Burnt Church (Esgenoopetitj) and Caledonia (Kanonhstaton). More recently, Elsipogtog and Unist’ot’en have shown that Land Back, as a movement, isn’t going anywhere.

Because as various BC Native bands said in a letter to the Canadian Minister of the Interior in 1911, “If a person takes possession of something belonging to you, surely you know it, and he knows it, and land is a thing which cannot be taken away and hidden.”

Sources and recommended reading

Behind the Trail of Broken Treaties, by Vine Deloria Jr.

Indians of the Pacific Northwest, by Vine Deloria Jr.

The Iroquois Struggle for Survival, by Laurence M. Hauptman

A Journey to Freedom: Richard Oakes, by Kent Blansett

In Defense of Mohawk Land: Ethnopolitical Conflict in Native North America, by Linda Pertusati

The One-and-a-Half Men: Jim Brady and Malcolm Norris, by Murray Dobbin

Halfbreed, by Maria Campbell

Prison of Grass, by Howard Adams

Bobbi Lee: Indian Rebel, by Lee Maracle

Contemporary Challenges: Conversations with Canadian Native Authors, by Hartmut Lutz

The Occupation of Alcatraz Island: Indian Self-Determination and the Rise of Indian Activism, by Troy R. Johnson

A Stó:lō – Coast Salish Historical Atlas

Land Back: A Yellowhead Institute Red Paper (2019)

Also

Proclamation of the Indians of All Tribes at Alcatraz (1969)

One reply on “Land Back: The matrilineal descent of modern Indigenous land reclamation”

This is a very informative posting that I learned a lot from. Thank you! I belong to an NYC-based grassroots anti-militarism and anti-imperialist organization called Nodutdol for Korean Community Development, and have been studying internally about Asian Settler Colonialism starting this year. We are trying to connect with nearby indigenous communities to learn more and to be part of Land Back movement, as a part of our own struggle against US imperialism, which has impacted our homeland for last 100 years. Anyway, thank you! Let us know if you know of a group we can connect with!