“The Individualist” sleeping on the job during the unemployed workers sit-down strike and occupation of the Post Office in downtown Vancouver, BC (1938)

by M.Gouldhawke (Métis-Cree), 2002

Red Riots of the Great Depression

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 was the beginning of the Great Depression and the effects were felt worldwide.

On October 17th of 1929, Vancouver’s unemployed raided a city relief office. On December 18th, hundreds of unemployed marched through Vancouver’s streets. The “snake march” became a popular way for demonstrators to tie up traffic and avoid police charges [as in a physical rush on the march by cops, not criminal charges].

Jobless people from across Canada flocked to Vancouver for its warm climate and in hopes of finding work. The popular saying was that “Vancouver is the only place in Canada where you can starve to death before you freeze to death.”

By December of 1930 long bread lines were common in the city, and hobo jungles and shanty towns started to spring up. By the summer of 1931 there were 42,000 jobless in British Columbia (BC). In September of that year, 237 relief camps were created outside the city, where men were forced to do road work. The men called them “slave camps.”

Women were encouraged to marry men rather than look for work, but many refused. Some women also took to “riding the rods,” hopping freight trains to travel and search for work. In February of 1935, thousands of women were active in trying to pressure the government to open and run free birth-control clinics.

In March of 1930, a group of hungry and homeless people armed themselves with iron bars and smashed the windows of the Woodwards building, looting the store for food. It became common to see people eating out of the garbage.

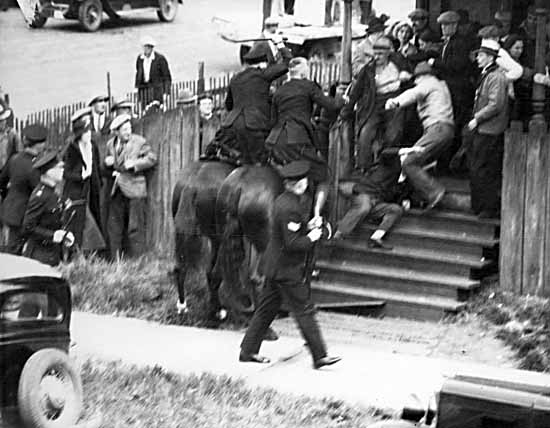

The first “Red Riot” of the Depression took place on August 1st of 1931, at the corner of Dunsmuir and Hamilton. The battle began when mounted police charged an “unpermitted” march led by a red flag. The marchers responded to the police attack by tearing up the pavement and ripping pickets from fences to use as weapons. The police claimed that citizens had also thrown rocks at them from houses.

20 police officers were injured, five ending up in the hospital, and eight demonstrators were arrested for rioting, including a 14 year old girl who had attacked a mounted policeman. Five homes were damaged as police chased fleeing demonstrators into nearby houses.

Police repression of the unemployed only led to an increase in anger, frustration, and agitation.

Hunger March of 1932

On March 3rd of 1932, 4,000 unemployed workers, squatters, and hobos marched through the city to protest the policy of cutting single men off relief if they refused to go to work camps. City council declined to meet with them and police on foot and horseback charged the group with clubs. The marchers used their flag and banner poles as lances, fighting back and defending themselves, sending two police officers to the hospital

Jobless on the Offensive

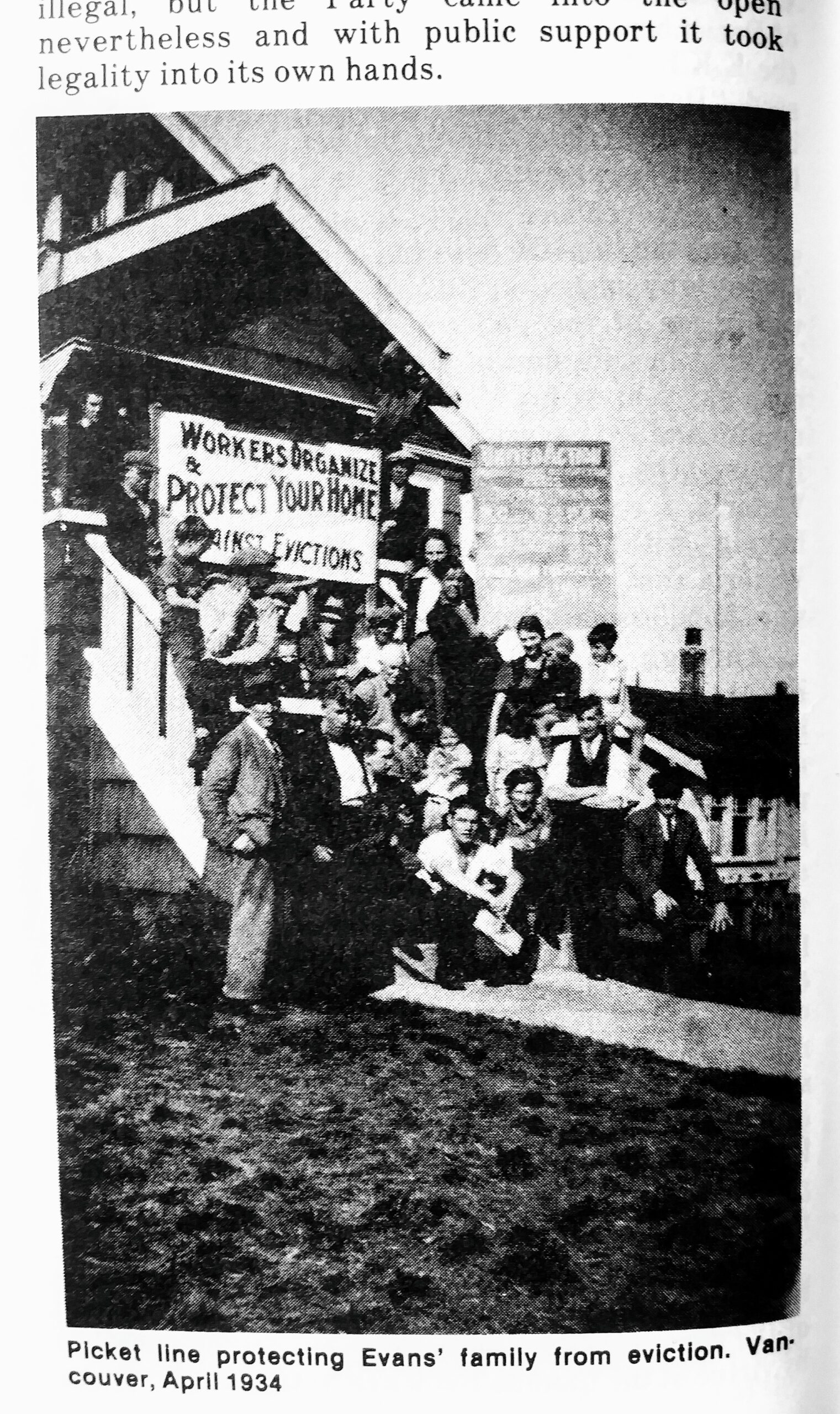

Unrest continued to grow through 1933 and 1934, as the Depression dragged on.

150 jobless men raided the Unemployment Relief Office in 1933, overturned registration files, tore out telephone connections, and fled the scene before police could arrive.

In March, 250 jobless and homeless men trashed a downtown shelter they had been staying in, and rioters smashed and looted the Men’s Institute at 1035 Hamilton Street.

Later, 19 men were caught after a mass dine-and-dash at a fancy downtown cafe and spent a month in jail for their actions.

On May 4th, 1934, the unemployed staged a large demonstration at city hall.

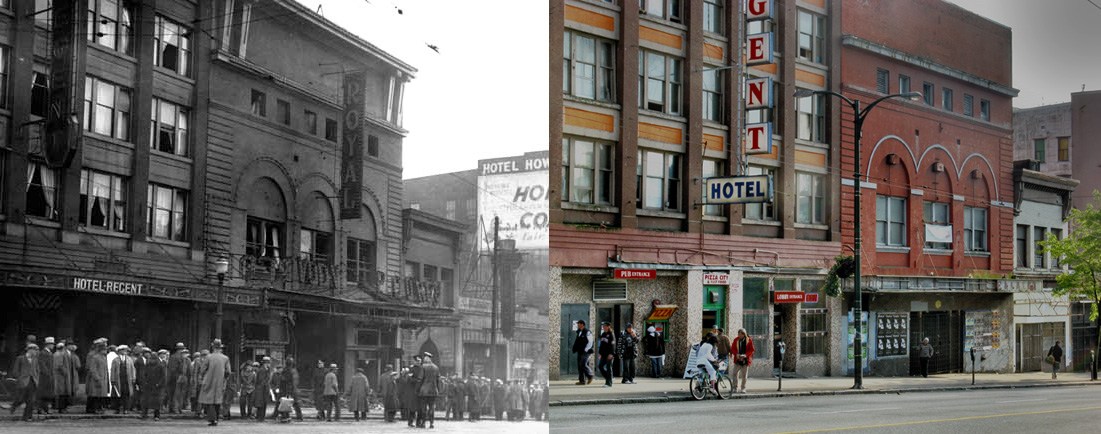

Bombing of the Royal Theatre

On the morning of March 20th, 1933, the Royal Theatre at 142 East Hastings was torn apart by a bomb. The Lobby and ticket office were destroyed and the explosion smashed the windows of other buildings on the block. One man was slightly injured and the manager of the theatre, W.P. Nichols, was jolted from bed as he slept in his suite directly above the theatre.

Nichols informed police that the Workers Unity League had met in the theatre the night before to celebrate the anniversary of the Paris Commune. Stink bombs had been used to scare away customers several months prior. The theatre had also been involved in a labour dispute a year before and a projectionists car had been bombed then. Despite this, the police decided that the explosion was not a result of labour unrest but simply a matter of a personal grudge.

Sometime after 12 noon on March 20th, street car operators found a coconut with a fuse and a skull-and-crossbones painted on it’s side, which they turned over to police.

A mass eviction of families on relief was carried out the same day.

Hudson’s Bay Store Occupation

The communist Workers Unity League established the Relief Camp Workers Union and called a strike on April 4th, 1935. The workers were outraged at the conditions in relief camps, and resented their isolation. On April 23rd, 1,000 strikers marched downtown and invaded the Hudson’s Bay Company store on Granville Street. Police claim that infiltrators had tipped them off to the strikers’ plans, and when they entered the store to remove the strikers, a battle broke out. Strikers fought back against the police and trashed the store, causing an estimated 5,000 dollars damage. The workers then marched from the store to Victory Square and attempted to flip over a police car into the street. The mayor appeared and read the Riot Act to the men who screamed at and denounced him. The demonstrators left the square singing “The Internationale” in defiance.

Later that night, police raided various strike headquarters and seized banners, posters, and newsletters. Crowds gathered at Carrall and Hastings Street once the word got out, and then smashed windows and clashed with the police. The next day, at a public meeting on the Cambie Street grounds, a call for a General Strike was made. It never materialized, but workers did participate in demonstrations and a one hour work-stoppage the next afternoon.

A month later, on May 18th, 1935, the relief camp workers tried to force their way into the Woodwards building and managed to briefly occupy the museum on the top floor of the public library until they were promised temporary relief.

May Day

During the depression May Day demonstrations grew in size and strength and peaked in 1935, as 35,000 people marched as part of the International Workers’ Day.

On-To-Ottawa Trek and Regina Riot

Thousands of BC workers traveled to Vancouver to demand jobs, the right to vote, and the right to organize. After the Vancouver mayor read them the Riot Act, the decision was made to take their demands to Ottawa. Almost 1,000 striking workers climbed atop freight trains on June 3rd and 4th, 1935. Local supporters fed them at each stop and hundreds joined them on their journey.

The Trek ended in Regina when the government stopped all eastbound freight movement. On July 1st, the trekkers held a rally to gain support in market square in Regina. Police hiding in furniture moving vans jumped out and attacked the crowd. Fighting lasted for hours, with local residents joining the strikers and throwing material from windows and rooftops at the police. The strikers overturned cars and built barricades in the streets. One police officer was killed and many bystanders and demonstrators were severely beaten in the street battle that was later called “the Regina Riot”.

Police Riot at Ballantyne Pier

On June 18th, 1935, 5,000 longshoreman marched along with the Women’s Auxillary down Alexander Street. They had been on strike since June 4th, when their employers declared collective agreement at an end and locked them out. Their mission was to talk to the scabs and to set up a picket line. Armed police had denied them this right previously. Police claim that they had stepped up infiltration efforts after the Hudson’s Bay Store incident, and that an undercover officer tipped them off to the strikers plans.

From behind boxcars, a battalion of police were hiding, and as the strikers approached the police fired rounds into the crowd. Tear gas was used and mounted policemen rode through the middle of the march swinging their clubs. Police chased fleeing workers throughout the neighbourhood, firing tear gas into homes and first-aid stations. Many workers were shot and beaten. At times, workers were able to fight back and defend themselves. The Vancouver Sun reported that nine policemen were in the hospital after the riot.

Spanish Civil War and Canadian Volunteers

In 1936, the Spanish Civil War broke out in response to a fascist military uprising. An anarchist revolution was made in much of eastern Spain. The industries of cities like Barcelona were collectivised, and many uprisings in the rural areas created agricultural and peasant communes. 1,448 volunteers from across Canada signed up for the communist-sponsored Mackenzie-Papineau International Brigade, to go and fight the fascists in Spain, despite official Canadian sanctions against doing so. The IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) in Canada recruited for the Spanish anarchist militias of the CNT (National Federation Of Labour) and FAI (Iberian Anarchist Federation). On February 11th, 1939, 31 veterans returned home to Vancouver. The fascists won the war, but anarchism in Spain survived.

Post Office Occupation

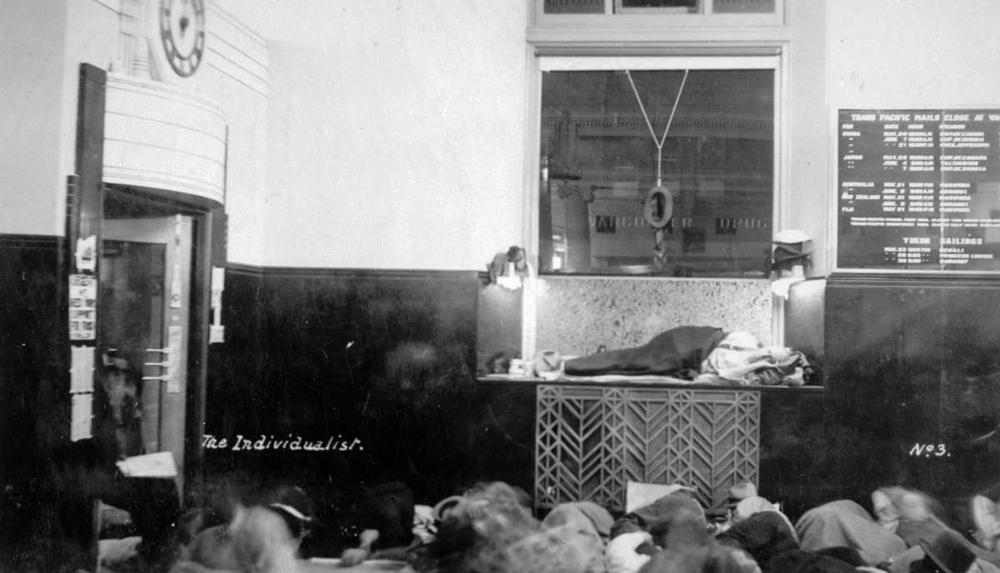

When relief camps closed in 1937, thousands of hungry, homeless, and unemployed single men landed in Vancouver. To publicize the need for relief, work, and decent wages, homeless and unemployed men occupied three city buildings on May 20th, 1938. The old Post Office at 701 W. Hastings street, the Vancouver Art Gallery and the Hotel Georgia were all targeted. After ten days, 600 dollars was accepted to vacate the Hotel Georgia. Over 1,200 men occupied the Post Office for one month. The Art Gallery was also occupied for one month. The occupations began with a large snake march consisting of four divisions. Three of the divisions entered the buildings, while another marched around the city aimlessly as a diversion for the police.

Police arrived at the Post Office a month later with an eviction notice, tear gas, billy clubs, and wire whips at 6:30 in the morning on June 18th. The eviction of the Post Office, called “Bloody Sunday,” saw 100 injured, 38 hospitalized, and 23 arrested. Trapped in a narrow corridor, they could not escape the clubs and whips of the police as they attempted to leave the building. Upon smelling tear gas, the men occupying the art gallery evacuated and rushed down to the Post Office to see what was happening.

The men were chased by police and ran east down Hastings and Cordova Streets, throwing rocks to defend themselves and breaking the windows of Woodwards and other businesses. Five policemen were injured in the street fighting. Total damage was estimated at 30,000 dollars.

Later that afternoon, 15,000 gathered at the Powell Street grounds to protest against police violence while 2,000 marched from Oppenheimer Park to the police station, smashed windows, and screamed for the release of those imprisoned. Another 2,000 protested in Victoria. All groups demanded the resignation of Premier Pattullo. A defense campaign freed most of the prisoners, but some remained in jail. The public protest forced the governments of BC and Canada to participate in an emergency relief scheme, the first welfare program implemented by these governments.

Escape and Riot at the Girls Industrial School

During the depression, crime rates soared. Industrial schools were designed as detention centres for “juvenile delinquents”. 84.5% percent of the girls arrested and sentenced to time at the industrial school were convicted for sexual relations. The usual sentence was two years, and girls were “trained” in domestic work. Not all of the girls were complacent, and in 1938, a mass escape was organized. In 1939, the girls rioted and it took 13 police to stop it.

Province Strike

In 1945, the Southam-owned “Province” newspaper tried to drop national standards for printers. Typographical unions in Winnipeg, Hamilton, Ottawa, Edmonton, and Vancouver joined in a wildcat strike against Southam in June of 1945. The strike was lost in the east, but in Vancouver, The Province could not publish for six weeks, until scabs from across Canada got the paper out from behind picket lines. Southam applied for and received an injunction and launched a 250,000 dollar lawsuit against the union. In response the union called for a boycott of the paper. Striking printers burned copies of The Province in the street. In some towns across BC, the circulation of the paper dropped to zero. Province sales plummeted, and the company eventually conceded to the union in 1948. The 40 month strike cost The Province its position as number one paper in BC. Subscribers refused to return to such an anti-union paper after the strike was over, and the paper lost money for the next seven years.

Earlier Radical History in Vancouver

The city of Vancouver is located on Squamish, Tsleil-Waututh, and Musqueam (Sto:lo) land.

Prior to European invasion there were many Musqueam/Sto:lo, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh towns and villages in the lower mainland area. The Musqueam town in what is now South Vancouver had a population of around 1,200 people. A village in Stanley Park was home to about 400 people. Throughout Vancouver there were many other small hamlets. The Sto:lo name for the west end of downtown around Georgia and Denman is Chelxwaelch. The east side, around the Clark and Hastings area is called Leglequi.

The first small pox epidemic reached the Coast Salish peoples in 1790. It had travelled north from Mexico and killed about two thirds of the population. For the next hundred years the Coast Salish peoples would be subjected to many more epidemics, most of them purposely spread by European settlers, including numerous outbreaks of influenza and measles. The gold rush of 1858 saw the first great influx of European settlers into Coast Salish / Sto:lo territory, and also the first reserves. Indigenous title to the land was ignored and the land was exploited, but not without resistance. In 1862, the new chief commissioner of land and works, Joseph Trutch, reduced reservation size by 92 percent, which sparked many protests.

Between 1884 and 1951, the traditional potlatch ceremony was banned by the colonial government. The potlatch was seen as a threat to attempts of assimilation. Potlatch ceremonies were large inter-community gatherings where wealth, hereditary rights, and property were redistributed through exchange of gifts. Coast Salish / Sto:lo people continued to have potlatches in secret. In 1888, a law was passed that made it illegal for Coast Salish / Sto:lo people to sell the fish they caught.

In 1907, Chief Capilano was charged with “inciting Indians to revolt” after he reported of his visit with King Edward VII of England.

In 1908, many Coast Salish / Sto:lo children were forced to attend Christian residential schools. They would stay for nine months of the year, spending half the time in class and the other half doing manual labour. Girls and boys were segregated and forced to do work according to European and patriarchal gender roles. Girls and boys were not allowed to speak to each other even if they were siblings. They were also prohibited from speaking their own languages or performing traditional dances. Many children defied these rules, associating with the opposite gender and running into the fields of tall grass in order to speak to each other in their Native languages. There were also attempts by the children to burn down the dormitories and schools.

The Streets of Vancouver

From 1873-1910, chained prisoners were a daily sight in downtown Vancouver, as they were put to work clearing and building roads under the watchful eye of a guard armed with a shotgun.

On December 31st of 1897, the chain gang went on strike, refusing to continue work, and were hauled back to jail and put on a water and bread diet. The prisoners held out for three days.

Most of the streets were named after wealthy property owners.

The Great Fire of 1886

1886 was the year of the Great Fire in which almost all of Vancouver burned to the ground. Land clearing fires on the Canadian Pacific Railway property quickly spread out of control, killing many and leaving 2,500 people homeless. A new city hall was built on Powell Street, but when it was finished the city claimed that it had no money to pay the builder. He decided to refuse them entry until he was paid and the city was quick to concede and pay him in full.

Early Class Warfare

The first Vancouver craft unions formed in 1887. Two years later, in 1889, class warfare erupted in Vancouver during a longshore strike as workers rebelled against uncertain employment on the docks and clashed with Canadian Pacific Railway special police. The strike forced Mayor David Oppenheimer into a compromise agreement with the workers.

The Fishermen’s Union formed in 1900. Indigenous men and women of the Fishermen’s Union were active in the 1900 strike and fought alongside white and Japanese workers.

In 1900 and 1901, Frank Rogers, a union organizer and socialist, led striking Vancouver fishermen on marches throughout the city. The workers faced-off against the militia and police, and Rogers was arrested during the strike of 1901.

In 1903, the United Brotherhood of Railway Employees (UBRE), a militant union that organized by industry, regardless of occupational and racial lines and in opposition to the craft unions, kicked off a strike when ticket clerks were fired by the company for union organizing on February 27th. Seamen, longshore men, transport workers, and Japanese labourers all walked off the job in sympathy strikes. The CPR recognized the threat posed by militant industrial unionism and class solidarity, and hired spies, undercover agents, strikebreakers and special police. Three days after the strike began Frank Rogers was shot and killed by CPR special police. His funeral was attended by every union in the city and more than 800 workers marched in the procession. The CPR payed for the special police murderer’s lawyer, and he was not convicted.

“Frank Rogers death was not only proof of the existence of class struggle, but also a reminder of which side had initiated the conflict.” – Jeremy Mouat

Vancouver’s First Socialist Organizations

The Vancouver local of the American-based Socialist Labour Party (SLP) formed in 1898 alongside the Socialist Trades and Labour Alliance (STLA). The STLA grew as a radical union alternative and made propaganda against the “business unionism” of the American Federation of Labour (AFL) and the Vancouver Trades and Labour Council (VTLC). The actions of the STLA led to a split in the Vancouver SLP and the formation of the United Socialist Labour Party (USLP). The USLP built a Socialist Hall on Main Street and was active in the fishermen strikes of 1900 and 1901.

In 1901, the USLP formed the Socialist Party of British Columbia and published the Western Clarion newspaper. In 1904, the Socialist Party of Canada was established, with a headquarters in Vancouver.

Settlers / Workers

The Vancouver chapter of the Knights of Labour formed in 1886. The Knights Of Labour was a militant industrial union, but was also a white-supremacist organization that was active in the Asiatic Exclusion League, boycotts of Asian businesses, and the race riots of 1887 and 1907.

In 1889, the Vancouver Trades and Labour Council (VTLC) was formed, as a more conservative and education-based organization that was also active in Asian exclusion and oppression. The VTLC constructed the Vancouver Labour Temple.

The British Columbia Federation of Labour (BCFL) did not form until 1910.

The Struggle of Asian Immigrants

The Chinese Benevolent Association (CBA) formed in 1899, in order to assist destitute Chinese workers. The CBA lobbied for relief during the Depression of the 1930’s and opened soup kitchens. More than 175 unemployed Chinese residents would starve to death in the 1930’s. The Chinese Workers Protective Association (CWPA) was also created during the Depression. Asian workers were generally paid two thirds to half the wages of white workers.

White-supremacists in Vancouver oppressed and excluded the Asian working class, and during economic depressions in 1887 and 1907, led anti-Asian riots in Chinatown. During the riot of 1887 more than 90 Chinese resident’s homes were burned down. Residents in Japantown in 1907, upon hearing of the racist attacks, armed themselves with clubs and knives.

Japanese residents threw rocks from rooftops at the white mob and managed to drive them back.

Japanese residents then armed themselves with guns and patrolled Japantown the next day, forbidding entry to outsiders.

The following day all Japanese and Chinese workers went on strike. Rumors spread of armed insurrection and the white population panicked and bought up weapons. The strike lasted for three days. The city police cordoned off Chinatown and Japantown for a week in an effort to keep things under control.

In the months following the riot Chinese and Japanese workers continued to organize their own unions and defense organizations in the city.

In July of 1917, Chinese shingle workers went on strike for shorter work hours and better conditions. Since 70% of the workforce in the industry was Chinese, most shingle factories in Vancouver were forced to close.

In 1919, the Chinese Shingle Workers Union (CSWU) was created and offices were set up in Chinatown. They engaged in a month-long strike against pay reductions and won.

The Japanese Camp and Mill Workers Union (JCMWU) was created in 1920, as a militant socialist organization, and also the first Japanese union to join the Trades and Labour Congress of Canada in 1927.

The Chinese Canadian Fisheries Worker’s Association (CCFWA) formed in 1978.

Industrial Workers of The World

The Industrial Workers Of The World (IWW) is an anti-capitalist union that has fought for revolution using direct action, and has a particularly strong history in Vancouver. Two miners from British Columbia, John Riordan and James Baker, attended the founding convention of the IWW in Chicago on June 27th, 1905. The IWW was formed by militant workers, anarcho-syndicalists, socialists, and communists who saw the need to organize “One Big Union”. The IWW set itself apart from the American Federation of Labour by organizing workers by industry rather than by craft or occupation. They refused to sign contracts with bosses, and rejected the dues check-off system, by which employers automatically subtracted union dues from paycheques. It was also one of the only unions of the time that organized all workers regardless of gender of ethnic background. One member declared that “all this anti-Japanese talk comes from the employing class.” The IWW strategy is based on direct action as oppossed to electoral politics.

Tsleil-Waututh (Burrard) workers from North Vancouver formed Vancouver Local 526 of the IWW in 1906. Soon nicknamed the “Bows and Arrows”, it was the first union on the Burrard docks. The Lumber Workers Industrial Union Local 45 (LWIU), the Lumber Handlers Local 526, and the Mixed Local 322 had been established by 1907, and had organized hundreds of workers. The Vancouver LWIU won the eight-hour workday for its members, removed tiered-bunks in logging camps, and forced companies to supply bedding. The IWW then went on to organize teamsters, miners, and railway workers. They had organized nine locals in British Columbia by 1913, and led six strikes involving some 10,000 workers. The IWW also organized transient workers, the unemployed, and recent immigrants, many of whom lived in the squatter jungles in the city; people that other unions looked down upon. Many of the founders of the Vancouver IWW had been active militants in the Socialist Trades and Labour Alliance (STLA).

The IWW denounced political action at a 1908 congress, and excluded known Socialist Party members. Along the west coast, and in Vancouver in particular, there was a strong movement among the IWW for regional autonomy and against the General Executive Branch. IWW members in Vancouver were strongly opposed to politics and parties. When the Socialist Party of Canada urged workers to vote for them in the 1909 elections, the IWW pointed out that only 75 of their 5,000 members were even eligible. This was because women, Asians, and non-residents or property owners had no voting rights at the time. IWW members felt that all governments served the ruling class and capitalism, and said that “a wise tailor does not put stitches into rotten cloth.” The Socialist Party of Canada (SPC) denounced the union as “so anarchistic, and therefore reactionary, as to clearly stamp it as an enemy of the peaceful and orderly process of the labour movement towards the overthrow of capital and the ending of wage servitude.”

It was in Vancouver that the nick-name “Wobbly” originated. A local Chinese restaurant keeper supported the union and would extend credit to its members. He pronounced IWW as “I Wobble Wobble”, and it quickly caught on.

The Wobbly Hall was at 112 Abott Street. Other meeting places included 61 West Cordova and 232 East Pender.

By 1912, the IWW boasted 10,000 members in BC.

The IWW fought a “free speech” fight in 1912, against a ban on public meetings, leading to the repression of many of its members, but also a lift on the ban. Vancouver police regularly attacked the Wobblies public meetings, and several riots broke out. Wobblies rented a boat and spoke to crowds off English Bay through a huge megaphone. In February the IWW called for a convergence in Vancouver and threatened a General Strike to oppose the ban on free speech. Wobblies warned that “the worker’s weapon – sabotage” would be put to use. J.S. Biscay declared in public meetings and to the press that “if they want to drown free speech in Vancouver they will have to bury us with it.” Towards the end of the struggle for free speech more than 10,000 people gathered to hear the Wobblies speak at the Powell Street grounds.

Listings for the IWW disappeared from Vancouver directories in 1912 after police and government harassment began in response to the IWW attempts to organize transient, forestry, and railway workers and open advocation of sabotage and class struggle. The IWW was banned in Canada between 1918 and 1919 under a “war measures act” as a seditious group, but members kept the organization alive underground.

Vancouver Wobblies re-opened a general membership branch in January of 2000.

Women’s Telephone Workers Union

The all-women workforce at the Burrard Inlet Telephone company (later called BC Tel and now Telus) went on strike in 1902, winning higher wages and paid sick leave. Previously, the workers had to pay the wages of their replacements when they called in sick. The company did not pay the women during the training period, which could last as long as six months.

The Telephone Workers Union joined the sympathy strike called by the Vancouver Trades and Labour Council during the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike. Of all the unions involved in the strike, the women telephone operators were the last group to return to work. They held out for two weeks after the general strike ended, but eventually returned to work on the company’s terms, which included the loss of their union.

In 1981, the union locked out management at several buildings in Vancouver. The workers ran an efficient and enhanced public service without the bosses. This “good work” strike pressured BC Tel into signing an improved contract with its workers.

Sabotage of the Cambie and Granville Street Bridges

At 4:30 on the morning of April 29th, 1915, two fires broke out simultaneously on the Cambie and Granville Street bridges. The Granville bridge fire was put out but the one on the Cambie bridge raged out of control and caused the collapse of the center span, destroying it. Firefighters determined that the fires had been set intentionally and many people speculated about the possible motives of the arsonists. Newspapers claimed that it was the work of “enemy aliens”, German spies bringing the First World War to Canada. The arsonists were never caught.

A few days later on May 3rd, fires were set on the Granville Street bridge and a woman claimed to have seen three men fleeing from the scene.

Albert “Ginger” Goodwin and the Vancouver 1918 General Strike

Albert Ginger Goodwin was a respected labour organizer and agitator who participated in several militant coal mine strikes on Vancouver Island. As a pacifist, he dodged the First World War draft but was hunted down on July 27th, 1918, and murdered by a special police officer. The working people of British Columbia were outraged and workers in Vancouver marked Goodwin’s funeral on August 2nd, 1918, with Canada’s first General Strike.

Soldiers rioted and attacked the Labour Temple during the strike and injured several people. The next day the soldiers returned to the temple, but workers fought back and drove the mob away.

Vancouver Solidarity with the Winnipeg General Strike

The great Winnipeg General Strike began at 11:00am on May 15th, 1919, and lasted until June 28th, 1919. On June 5th, 1919, Vancouver workers set off solidarity strikes. Street railway men, electrical workers, telephone workers, most civic employees, sugar refiners, metal workers, and coastal shipping workers walked off the job in sympathy with the struggle in Winnipeg. 1,200 street railway men held out until June 30th, while other workers held out until July 3rd, and telephone workers struck up to July 16th, far past the end of the Winnipeg General Strike on June 26th, 1919. Large football matches became a popular pass-time with the strikers.

Sources and books for further reading

Labour, Work and Working People, by SFU’s Labour Initiative, the Pacific Northwest Labour History Association, the Vancouver and District Labour Council and the BC Heritage Trust

Working Lives: Vancouver 1886-1986, published by New Star Books

Fighting for Labour: Four Decades of Work in British Columbia, 1910-1950, published by Sound Heritage

100 Anniversary: Vancouver District Labour Council, 1889-1989, by Adele Perry

Fighting Heritage: Highlights of the 1930s struggle for jobs and militant unionism in British Columbia, edited by Sean Griffin

Plunderbund and Proletariat: A History of the IWW in BC, by Jack Scott

Where the Fraser River Flows: The IWW in BC, by Mark Leier

Work and Wages: The Life and Times of Arthur Evans, by Ben Swankey and Jean Sheils

Opening Doors in Vancouver’s East End, published by Sound Heritage

Indians at Work, by Rolf Knight

Drawn to Change: Graphic Histories of Working-Class Struggle

A Sto:lo – Coast Salish Historical Atlas

A Century of Service: 1886-1986, by the Vancouver Police Department

More info

Preview #12: “Working on the Water, Fighting for the Land: Indigenous Labour on Burrard Inlet”

Working on the Water, Fighting for the Land

Land, Labour and Loss: A Story of Struggle and Survival at the Burrard Inlet

Review: Reading the Riot Act, A Brief History of Riots in Vancouver (2005)

Squatting in Vancouver – A Brief Overview (2002)

A Rent Strike in Vancouver – Anders Corr (1971)

Direct Action Gets the Goods: A Graphic History of the Strike in Canada (2019)