Indigenous insurrection in Australia over death in police custody

By M.Gouldhawke (Métis-Cree)

Wii’nimkiikaa (It Will Be Thundering)*, Issue 2, 2005

Hundreds of residents of the Aboriginal community of Palm Island, Australia, burned down the local police station, court building and the housing barracks of local police officers on November 26, 2004, after a coroner’s report on the police custody death of island resident Mulrunji Doomadgee, a 36-year-old Aboriginal man, was read aloud to a community meeting.

The report indicated that Mulrunji (also known as Cameron) suffered four broken ribs, a ruptured liver and a ruptured portal vein during an arrest for public drunkenness. He died about an hour later in police custody. Witnesses reported seeing him being beaten.

“I believe the same as everybody else on this island – that he was bashed to death in the cell,” declared Mulrunji’s 15-year-old son, Eric.

The local police were forced to hide out in a hospital during the rebellion and then flee the island, while about 80 cops were flown in by an army Chinook helicopter from Townsville and a plane from Cairns. Authorities declared an “emergency situation” under the Public Safety Preservation Act, allowing police to close the airport, take control of resources and buildings and close roads. A local school was seized and classrooms were made into temporary holding cells, offices and police dormitories. Some white contractors, public servants, teachers and other residents were evacuated from the island.

Tensions had been rising in the community since the beginning of the week, when some 200 angry residents marched on the police station. The following day, a police car was assaulted by rock throwers after officers on patrol stopped to take down a road block. The cop that arrested Mulrunji Doomadgee, Senior Sergeant Chris Hurley, left the island the same day, “for his own safety”.

A group of Aboriginal teenagers upped the ante the day following, when they attacked the police station and the officer’s housing barracks, breaking windows and damaging cop cars. The November 26 rebellion was the culmination of these escalating reprisals to police brutality.

The incendiary conflict at Palm Island was also a vivid reminder of the February 15, 2004, street rebellion in the Aboriginal neighborhood of Redfern in Sydney, sparked by the police murder of a 17-year-old Aboriginal youth named Thomas Hickey.

Redfern riot, Sydney, 2004

“It is very much a White, Black issue,” said Palm Island resident Nicky Willis. “The young people of Redfern were full of anger and now the young people here are full of anger.”

“What is going on Palm Island is a genuine reflection of how all Aboriginal people are feeling at this stage across Aboriginal Australia” said Mulrunji ‘s cousin Murrandoo Doomadgee (Yanner?).

In the days following the Palm Island revolt, paramilitary “Tactical Response” police squads carried out raids on homes and arrested 19 men and two women. Young Aboriginal children were made to lie down on the ground at gun-point while masked officers kidnapped and detained their family members. Agnes Wotton, age 65, is facing life imprisonment after being charged with “riotous demolition of a building”. Two young men, both 18 years of age, have already been sentenced to six months in jail after they pled guilty to “breaking and entering” during the riot.

At the first court appearance for 18 of the arrestees in Townsville, on the mainland, a crowd of about 50 supporters disrupted the proceedings, shouting “bullshit” when 40-year-old defendant John Clumppoint’s history was read aloud. The supporters then rallied outside the courthouse, holding placards reading “Police Service: Murderers and Liars”. Strict bail conditions were placed on the defendants, prohibiting them from returning to Palm Island or attending Mulrunji Doomadgee’s funeral.

“All Aboriginal people know the court process is a sham,” said one person. “When you go in there, you have to say ‘yes your honour’ and bow to the judge, who sits many metres above you, looking down on you. So when you go into the courts, Aboriginals think… you’re in an area where you’re not going to win.”

On December 9, about 1,200 people took part in a march against police brutality through Townsville to its police station. Lex Wotton, one of the rebels arrested on Palm Island, publicly disobeyed his bail conditions in order to join the march, drawing cheers and applause from the crowd. Townsville police officers decided against arresting Wotton for the infraction.

Murrandoo Yanner addressed the rally, saying, “Stop the Black on Black violence. If you are going to go to jail, go to jail for something honourable, deck that policeman hurting your brother, burn that police station protecting a murderer.”

Two days later, Mulrunji Doomadgee’s casket was draped with the Aboriginal flag at his funeral on the island, while about 2,000 people marched through the city of Brisbane in solidarity. On December 18, about 50 people demonstrated to demand that the 19 arrested men be allowed to return to Palm Island. A second national day of protest against Aboriginal deaths in police custody was held on February 13, 2005.

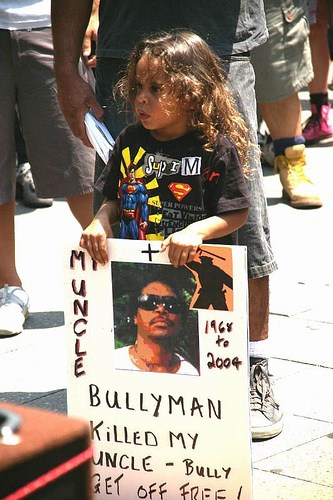

Family member holds sign with photo of Mulrunji Doomadgee

At the end of February, 2005, four consecutive nights of rioting took place in the poor white neighborhood of Macquarie Fields in Sydney, after two youths died in a police chase. By the third and fourth nights of the conflict, Aboriginal and Middle Eastern youths were reportedly heading to Macquarie Fields to join the battle. A few days later, youths in the town of Kempsey, just north of Sydney, were inspired to take on the cops as well.

On March 3 of 2005, the first inquest into Mulrunji Doomadgee’s death was called off due to accusations of bias. In a series of attacks throughout the month of March, Palm Island residents hurled rocks at police residences, vehicles, and the police station. A second inquest of Doomadgee’s killing began as March ended. Police fearing the recent spate of attacks asked for the inquest to be split between Townsville and Palm Island, so that cops and medical professionals could testify on the mainland.

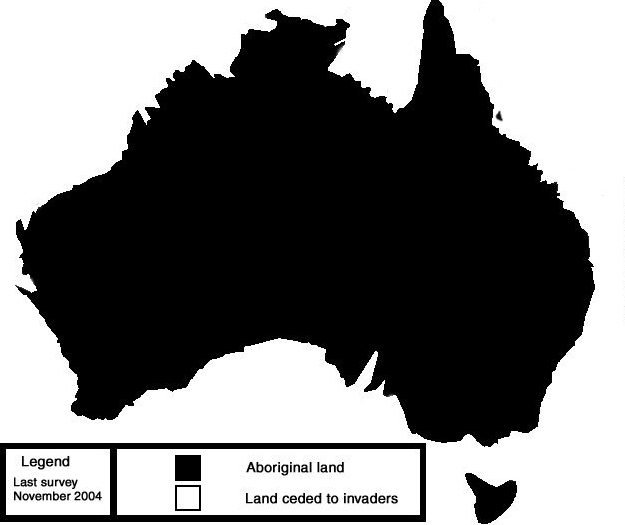

Palm Island is the traditional territory of the Manbarra people. It became a reserve in 1914, and was expanded as a sort of prison colony for Aboriginal peoples from across Australia in 1918, including mothers of mixed-blood children and Aboriginal convicts. No Indigenous person was allowed to leave the Island without the government superintendent’s permission, a nightly curfew was imposed, and all outgoing mail could be censored. Speaking Aboriginal languages was forbidden.

Article sources

Melbourne Indymedia dot org

Redfern riot, 2004

Palm Island insurrection, 2004

2004 Palm Island death in custody (wikipedia)

Blak lives betrayed—Mulrunji Doomadgee (2020)

White Man’s Manslaughter. Black Man’s Murder. White Man’s Riot. Black Man’s Uprising (2016)

“The violent clashes between police and protestors in Kalgoorlie yesterday [2016] followed the charging of a 55-year-old man with manslaughter over the death of a 14-year-old Aboriginal boy, Elijah Doughty.” (See the above linked article)

Publication note

* Wii’nimkiikaa (It Will Be Thundering), was a short-lived but sparky Indigenous resistance print magazine with an international focus (intended only for an Indigenous readership), which was started, edited and designed by an Anishinaabe comrade in 2004.