“Sir George Williams University stands condemned” (Montreal, February 11, 1969)

By M.Gouldhawke (Métis-Cree)

Originally published November 2019, revised and edited up to June 2024

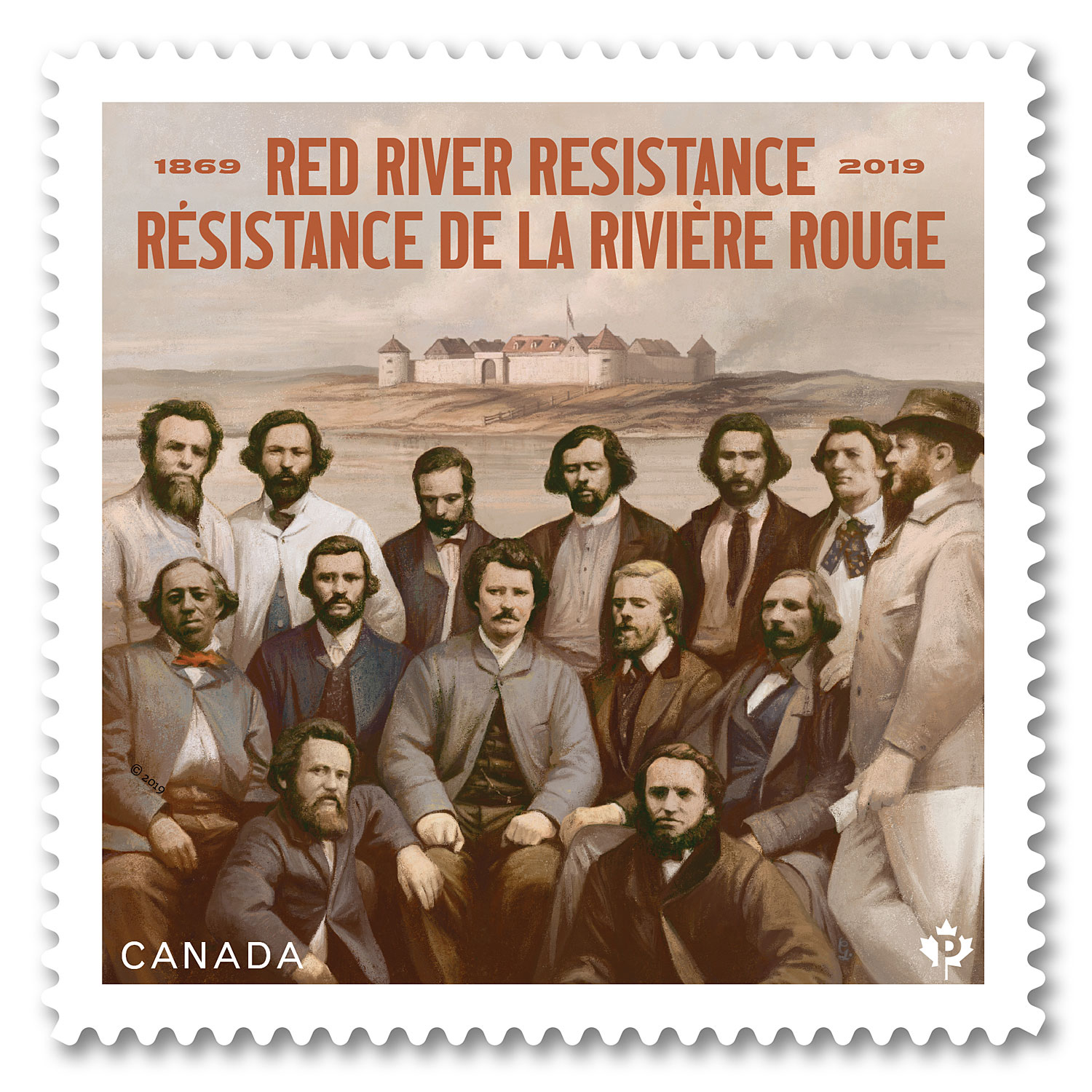

2019 marked the 50th anniversary of the occupation of Sir George Williams University in Montreal in 1969 by Black and Caribbean students who were protesting racist treatment by professors at the institution, as well as the 150th anniversary of the Métis Nation’s re-occupation of Fort Garry at Red River (Winnipeg) in 1869.

Two perhaps seemingly unrelated events, but both providing examples of resistance to Canadian imperialism, as the events in Montreal spilled over into the Black Power Movement of 1970 in Trinidad and Tobago which targeted Canadian banks in that country, while the Métis Nation in 1869 had been resisting Canada’s arbitrary purchase of their territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company and the attempt by Canada to impose its political and economic system on the Métis without their consent.

Saskatchewan Métis writer and community organizer Howard Adams wrote in 1988 that the action taken by Black students in occupying Sir George Williams University in 1969 was the first to seriously put Canada’s institutional racism to the test.

Remember/Resist/Redraw #18: The Sir George Williams Protest

Remember/Resist/Redraw #18: The Sir George Williams Protest

Another Métis organizer, Harry Daniels, was inspired in 1969 by Chicago Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton’s speaking engagement at the University of Saskatchewan in Regina. Daniels reportedly met with Hampton at the time and then took part in a Regina vigil held in memory of the Black Panther leader the week after he was killed by Chicago police.

Important to any discussion of Métis and Black solidarity (and Native and Black solidarity generally) is also the fact that these cannot be understood as mutually exclusive identities, since many of our relatives are in fact both.

Black Power in Trinidad and Tobago against Canadian imperialism (a shot from the documentary film Ninth Floor)

“When I came to Canada [from Barbados], I did not view myself as an immigrant,” recalled former student organizer Anne Cools (who later became a Conservative politician) in the 2015 documentary film “Ninth Floor,” which depicts the 1969 Montreal events and their connection to the Black Power movement in Trinidad and Tobago.

“I thought of myself as moving from one part of the British Empire to another,” Cools explained.

One of the Métis militants who resisted Canadian encroachment at Red River in 1869 was Maxime Lépine. In the early 1960s, Lépine’s great-grandson Howard Adams was a student at the University of California-Berkeley and attended a speech by Malcolm X. The speech was incredibly inspiring according to Adams and prompted him to reconnect with his own Métis culture by contacting his uncle Mederic McDougall, the family member he remembered as being most proud of Métis resistance history. In fact, McDougall was a socialist and a co-founder of the Saskatchewan Métis Society in the 1930s (as well as the grandson of Maxime Lépine.)

Howard Adams went on to be involved in the initial stages of the university occupation movement at Berkeley in the ’60s and then moved back to Saskatchewan after completing his degree. Back home in Métis territory Adams became a teacher, writer, and a prominent community organizer in the cross-Canada Red Power movement of the ’60s and ’70s.

Colonial commemorative stamp attempting to recuperate the Red River Resistance of 1869-70, released in 2019 for the 150th anniversary

Colonial commemorative stamp attempting to recuperate the Red River Resistance of 1869-70, released in 2019 for the 150th anniversary

Adams continued to be influenced by the theory and practice of Black resistance as the years went on. In his two main books, “Prison of Grass” (1975) and “A Tortured People” (1995), and in various articles he wrote, Adams frequently quoted and referenced radical Black, Caribbean and African writers such as Frantz Fanon, Oliver C. Cox, James Boggs, Kwame Nkrumah, E. Franklin Frazier, Chinweizu Ibekwe, Walter Rodney, Amiri Baraka, and Amilcar Cabral.

A major part of Adams’ contribution to radical Indigenous theory in Canada was his insistence on the inter-relatedness of imperialism, colonialism, racism and capitalism, and this can be seen as indebted in large part to his study of radical Black, Caribbean and African thinkers and organizers.

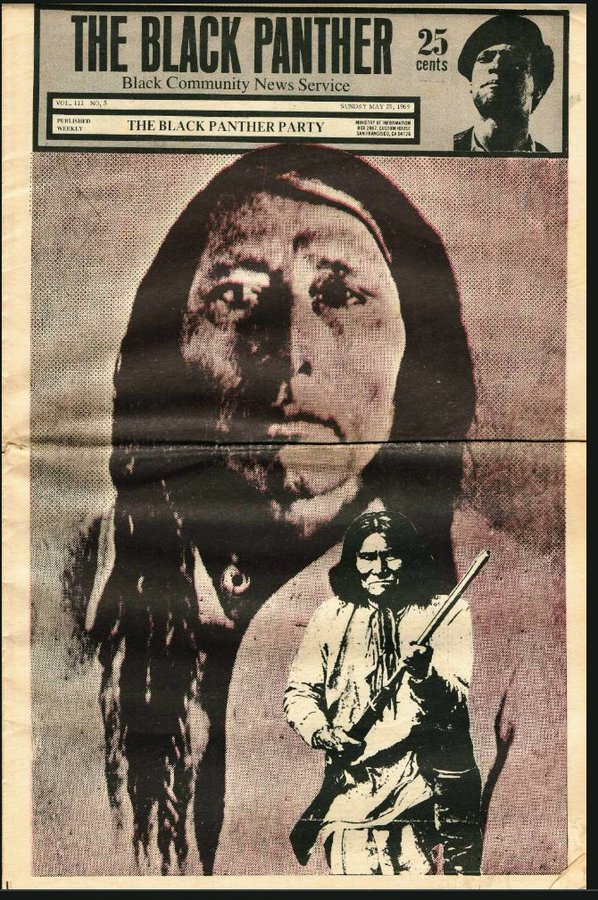

Cree chief Poundmaker and Apache leader Geronimo on the cover of the Black Panther Party newspaper out of the San Francisco Bay Area in 1969. Poundmaker’s people were part of the Northwest Resistance of 1885, which also involved the Métis

Howard Adams was not the only Métis connection to the ’60s and ’70s Black Power movement. In 1969, Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton made a speech at the University of Regina in Saskatchewan and had a meeting with Métis leader Harry Daniels, just three weeks before Hampton was killed by Chicago police.

“The Indians may have a different name but they are still fighting the same problems of fascism, imperialism, capitalism and exploitation,” said Hampton during his speech in Regina, according to the Leader Post newspaper.

“He talked about the way police treat Indigenous people in Canada,” recalled event attendee Barry Lipton.

On December 12, 1969, more than 100 people, including Harry Daniels, held a torchlight march in downtown Regina, in memory of Fred Hampton, killed the week before, and 19-year-old Nick Mjazyk, who had been shot and killed by Regina police on December 8.

The connections between Native and Black resistance movements in the ’60s and ’70s also went beyond the Métis, who are just one particular Indigenous people.

Black activists like Dick Gregory joined the Coast Salish “fish-in” struggle in the Pacific Northwest in the mid-1960s.

Comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory (center) joined by Edith and Janet McCloud (left)

November 20, 1969, saw the start of the re-occupation of Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay Area by the Indians of All Tribes, making 2019 also the 50th anniversary of that historic moment in the Red Power movement.

The Bay Area had been the birthplace of the Black Panther Party, and member Assata Shakur visited the Alcatraz occupiers in 1970, later commenting on her time there in her autobiographical book “Assata”.

“I will never forget the quiet confidence as they went about their lives calmly, even though they were under the constant threat of invasion by the FBI and US military,” Shakur wrote.

“They had many of the same problems we had: education, organising the people to struggle and raising consciousness,” Shakur pointed out. “They damn sure had the same enemy, and they were doing as bad as we were, if not worse.”

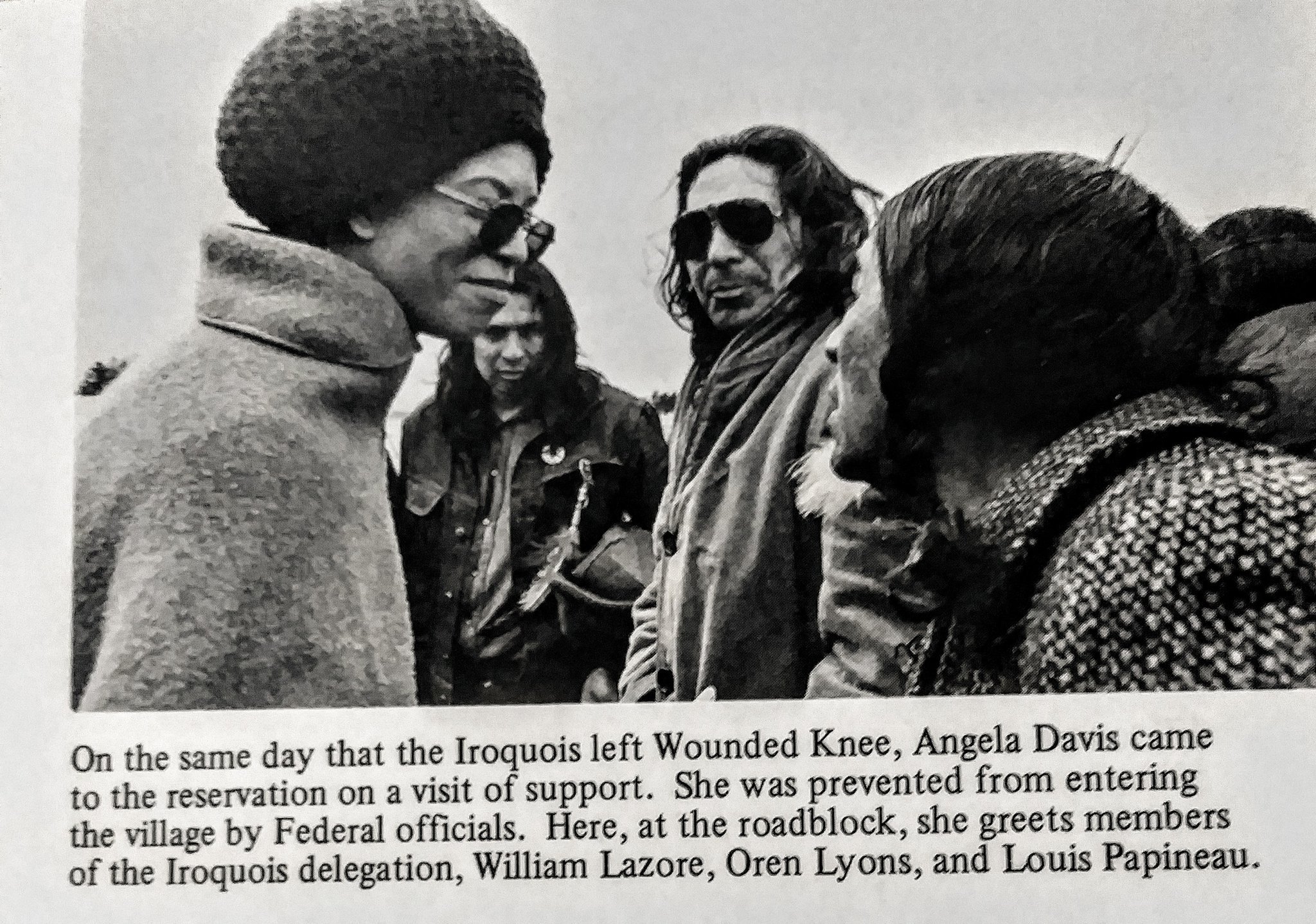

In 1973, Angela Davis, an associate of the Black Panthers and an organizer in her own right, visited the Lakota people’s re-occupation of Wounded Knee at the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota.

George Manuel Sr. (Secwepemc) and Marie Smallface-Marule (Blackfoot), two prominent Indigenous leaders in the National Indian Brotherhood in Canada, visited Tanzania in the 1970s and were influenced by Julius Nyerere’s philosophy of African socialism.

Other Native writers and organizers in Canada at the time, like Waubageshig Harvey McCue and the Native Alliance for Red Power (NARP) studied and made reference to Frantz Fanon’s writings, and in the case of NARP, the Black Panthers as well.

Institutional Racism

Howard Adams at Indian Culture Days at the University of California-Davis, 1980 (Photo: Hartmut Lutz)

An excerpt from Howard Adams’ article in the book of collected texts, ‘Racial Oppression in Canada’, 1988

by Howard Adams (Métis)

The study of institutional racism is a relatively new approach to the analysis of colonization in western societies. The emphasis of racial studies by social scientists has focused on the pathologies of Indigenous minorities, and possible solutions for their adjustment to the white middle-class society. However, from another perspective, it is possible to analyze institutional racism of white supremacy societies.

Institutional racism includes an ideology of one group proclaiming racial superiority over another group that is subordinated in the society. The differential access to power, privilege, and prestige by the dominant group, as well as the structure of economic, political, and educational inequality, are basic features of institutional racism. It is laws, customs, regulations, and practices that are racist, regardless of the personalities in power. Individuals living in a white supremacy society are often unaware of their discrimination. This lack of awareness makes their prejudiced behaviour less amenable to reform.

Institutional racism is a subtle and disguised process operating in established and respected bureaucracies of the society. These common offices, i.e. manpower, immigration, etc., contain structural factors of racism which are largely invisible and oblique, but nevertheless result in unjust treatment of Native people. The essence and ethos of bureaucratic organization in western societies is white superiority. Since racism pervades the policies and regulations of some institutions at the time of their creation, they will persist throughout the lifetime of such institutions. The Indian Affairs Bureau exemplifies an institution that prestructures and predetermines Native people’s participatory relationship. Racial minority members who are powerless and outsiders have no alternative but conformity and submission to the operating norms of the institution. Even if certain discriminatory policies are modified, i.e. changing college admission criteria for minorities, inequalities in other parts of the institution will sustain racism, i.e. low quality of ghetto schools. Once racialist policies have been institutionalized, the role of the prejudiced person is either of little importance or plays a minor role because the operating bureaucratic policies and regulations function naturally in discriminating against Native persons. In other words, a white person acting in his/her official capacity is also victimized by the racism of the institution.

Institutional racism is a system of policies and regulations that perpetuates inequality by the state. It is interrelated and reinforced across organizational and bureaucratic sectors. The consequences are the primary indicators of institutional racism. For instance, in Saskatchewan the prison population is comprised of approximately 50% Native males and nearly 90% Native females. Yet, Indians and Halfbreeds constitute only 8% of the total population. A white supremacy society is not maintained exclusively by prejudicial attitudes of individuals, such as judges, policemen, and teachers, but by the institutionalization of inequality. It can operate independently of individual prejudice. On the other hand, it is possible for institutional racism to be reduced to personal attitudes because white officials eventually surrender to the doctrine of the institution, thus responding to coloured persons in a prejudicial manner.

Yet there remains an ambiguity between personal and institutional racism because of the uncertainty of the boundaries. It is not always easy to state whether discrimination is strictly personal bigotry or the consequences of institutional racism. Prejudice may be both subjective and objective at the same time. It is subjective when a response demonstrates the personal prejudices of an individual and objective when the response shows the institutionalized acts of inequality located in the hierarchies of bureaucracy. The manifestations of inequality will vary along such lines as the degree of emotional intensity, extent of effect on the minority groups and the degree of visibility of the discriminatory act at the time. Institutional racism is less difficult to prove than personal prejudice, because the former can be measured in objective terms, such as ghetto schools, minority slums, infant mortality rates, school drop-outs of minorities, etc. Another instrument of measurement of institutional racism is “credentialism,” meaning degrees in medicine, law, teaching, etc.

One of the early establishments of institutional racism in Canada was the church, particularly the Roman Catholic church which initiated vigorous efforts to “civilize the heathen savages”. This was the forerunner to a succession of similar state institutions that served the interests of a white supremacy society. These racial institutions continued to develop over a period of many decades.

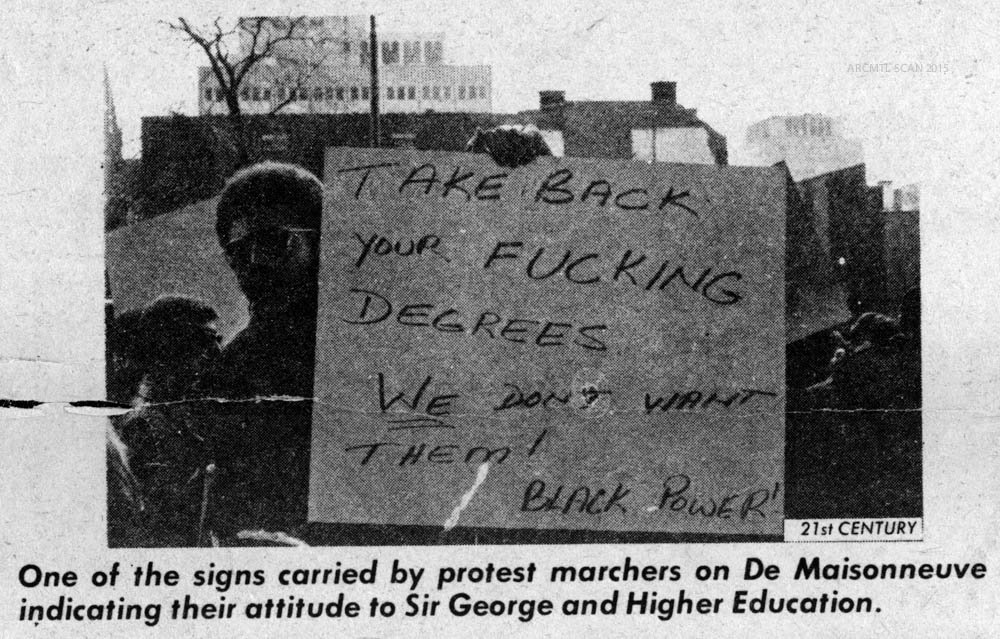

Canadian society specifically had never been put to a serious test regarding its institutional racism until 1969 when the Black students at Sir George Williams University occupied the computer centre. Analyzing the situation two years later, one of the students concluded that the problem “…is to be found in the racist nature of the country and all its institutions” (Forsythe, 1971: 114). Since almost all the students involved in this experience were Blacks from the West Indies, it became a racist confrontation. In their struggle with Canadian law, the Black students soon realized that they were dealing with a racist court in its judicial capacity as an oppressive mechanism. In referring to the Canadian government and political figures, Forsythe states that “the same racist tendency to prejudge on the basis of colour was evident here…” (Forsythe: 132). Forsythe further claimed that “it should be stated… that this type of reaction is hardly sufficient to offset the stark realization by the minority of black people that Canada is indeed racist” (Forsythe: 139).

Howard Adams at a sociology & anthropology conference in Banff in 1969, speaking on Canadian racism

“Just one word about the business of racism in Canada, I have said this many times before, and I think it is because I see the institutions of Canada so deeply entrenched and so effective in the socialization process of the Canadians.

The Canadians are the most arrogant and the most self-righteous people in the world. They are the people who are always so willing to offer their services to the United Nations for the troubled spots of the world, to go and solve the racial conflict or any kind or turmoil between groups of people – not recognizing that they themselves are the most racist-minded people in the whole world.

And I might say that in the parts of the world that I have traveled in – they have not been that extensive but have been reasonably extensive – I have found that the people know Canadians are racists. We are the only people who really don’t know. We are fooling ourselves into believing this. No, we are just kidding ourselves, wanting to give ourselves a very nice feeling about the fact that all the racism is in the terrible part of the United States, in the southern part, and in Africa.”

Also

How the Sir George Williams protest changed the conversation about racism in Canada (CBC)

Regina’s radical university students hosted the Black Panthers in 1969

“’70: Remembering a Revolution” in Trinidad and Tobago

I Grew Up With My Métis Roots. I Dug Deep To Find My Black Ancestry, by Larissa Crawford

To shape the future, look to past Black Canadian activism, by Bee Quammie