Originally published in the book Black Seed: Not on Any Map (2021)

By Mike Gouldhawke (Métis-Cree, family from Treaty 6 territory)

When I think of the potential and the reality of Indigenous anti-politics, I imagine a line that runs from the Métis and Cree resistance of 1885 to the Haudenosaunee land reclamation movement that kicked off again in the 1950s and still continues today in 2021, at 1492 Land Back Lane on Six Nations of the Grand River territory.

Different times, conditions, territories and peoples, but also a connection that was made in 1965 when Haudenosaunee and Kanien’kehá:ka Chief Rastewensereronthah reached out to Métis socialist Malcolm Norris, asking him to republish in his Saskatchewan-based Native newspaper an article on the illegitimacy of the Canadian and British states written by Karoniaktajeh (Louis Hall). Different times, places and peoples, but a common struggle, sometimes successful, to kick colonial cops out of our communities.

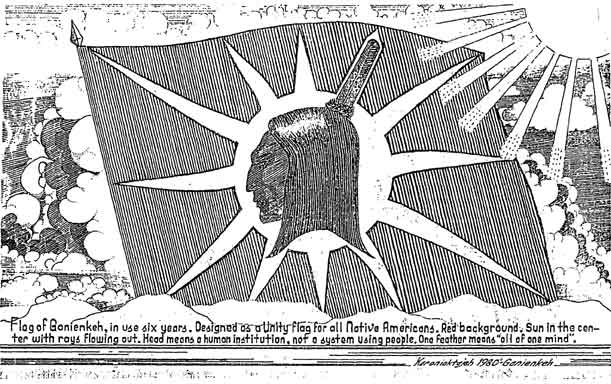

Karoniaktajeh, the designer of what’s now often called the Warrior Flag, described it as having been “designed for all Indian nations”. As representing “equality for all Indian Nations.”

Since the so-called 1990 Oka Crisis and its many solidarity blockades, the Unity Flag is now seen coast to coast, from the west with an August 2020 Wet’suwet’en railway blockade in solidarity with 1492 Land Back Lane, to the east with the Mi’kmaq fishing struggle continuing into 2021, often alongside each nation’s own flags.

For my part, I was inspired by the cross-country blockades of 2020 in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en struggle against a natural gas pipeline. The Listuguj Mi’gmaq community on the east coast, for instance, held a solidarity rail blockade for 25 days. At the Kanien’kehá:ka / Haudenosaunee community of Tyendinaga, two solidarity camps did not go quietly when Ontario Provincial Police raided and trains started running again, as burning blockades were set up at two locations along the line.

In solidarity with Tyendinaga, the Kanehsatà:ke community blocked the highway that runs through their reserve and Gitxsan people back west blocked first a railway line, then a highway, after cops arrested hereditary chiefs at the railway, eventually forcing the cops to release the hereditary chiefs.

I remember visiting in the 2000s what felt like territory the Haudenosaunee had at least partially liberated, during a heightened period of struggle in multiple communities, namely Kanehsatà:ke, Tyendinaga, and Six Nations of the Grand River. I remember hearing elders and other community members explain their sharp perspectives on their people’s struggle.

To me, these land reclamations and direct actions are part of an anti-politics of visiting, of shared social space in the face of outside forces of divide and conquer. The strength of Haudenosaunee communities, in the face of everything arrayed against them, was impossible to miss.

Of course, Canada’s conquest remains forever incomplete, as continuous cross-country Indigenous resistance reminds us. Ultimately the struggle is about our lands, waters, the air we breathe, and all our social relations that depend on them. Not just human relations, but relationality itself.

I remember the friendships I made, as a Métis and Cree person, with Haudenosaunee people, some of whom moved out west and not all of whom are still with us in physical form, but definitely are still here in our memories and in spirit.

I think of the Secwepemc and Anishinaabe resistance to the cops in 1995. I remember Dacajeweiah (Splitting the Sky) of the Haudenosaunee and Kanien’kehá:ka speaking at events and benefits for Secwepemc prisoners of war a few years later. Of him speaking about having been a prisoner himself in Attica during the uprising of 1971. This was my introduction to the history of Indigenous resistance.

For our peoples, the cops and prison guards are a roadblock along the way to freedom and restoring relations, but also an occupying army serving the settler colonial state. Cops and screws serve politics, the institutionalized separation of decision and action and of people and property. The institutionalized form of politics, the State, serves itself, when not busy providing services for other colonizers and capitalists, and protecting their precious property.

When I think of Indigenous resistance to this kind of domination, I remember a story, written by my own Swampy Cree ancestor James Settee in the 1880s, of a battle between brothers, where the younger brother, the anti-authoritarian Rabbit beats the powerful and power-hungry older brother, the North Wind.

The younger brother Rabbit, after his victory, says “I mean to be good and kind to all.”

“It will so follow, I will have enemies but they will never conquer me,” says Rabbit. “I will stand to the end of time.”

Settee, in writing this, was retelling a story he had heard when he was young, in 1823, told to a gathering in his father’s community by an elder, in what’s now called northern Manitoba.

At the end of the tale of the battle, the elder who retells it says there is a moral lesson to the story, but who’s to say what it is? Another elder joins in and says, “I can only say what I think of this story.”

“There is to be a great revolution in the world,” says the elder. A war, where the North will try to subdue everyone else, but the South will resist and the “Rabbit Kingdom” will join forces with them and defeat the North. The whole community cheers.

To me, the very structure of Settee’s story, the way the community collectively retold and re-interpreted it, reflects an anti-political sensibility, itself echoing the anti-political struggle of Rabbit and the South against the domination and greed of their older brother, the North Wind. Not just a story from the past but also a lesson for the future.

I’m reminded of reading the specifics of the Cree worldview, as redescribed by Cree elders in a survey by Cree/Dane-zaa writer and musician Art Napoleon.

The values and principles “most consistently identified were tapahtîmisowin, a form of humility roughly implying, ‘to never think higher of yourself than others,’ and kihciyimitowin, ‘an ultimate, sacred-like respectful thought for one another.’”

I think of miyo-wîcêhtowin, the intentional cultivation of good relations, in contrast to the tolerance of harmful ways of relating to each other. I think of sihtoskâtowin, supporting each other and pulling together to strengthen each other.

I think of the importance to the elders of tâpwêwin, truthfulness, as redescribed by Cree writer Harold Cardinal. And I wonder what place there could be in our culture for tolerance of politics, the separation of the people from decision making and the art of deceptive persuasion by the politician.

Plains Cree participation in the militant 1885 resistance was only possible because band chiefs did not have authority over matters of war, those being the responsibility of the war chief and warrior societies, which the band chief could only advise against, but not overrule.

As Kainai Nation (Blood Tribe / Blackfoot Confederacy) writer Marie Smallface-Marule explained in 1984, with the Prairies tribes, “there has always been a strong tradition of decision-making by consensus rather than by individuals in authority.”

“Under this principle,” Smallface-Marule further detailed, “all members of the community had to be involved in decision-making.”

All of this is to say that when I think of Indigenous anti-politics, I don’t think of an ideal of perfection to achieve in some distant future, but I do think of Indigenous direct action past and present, and the social network from which it grows. A social network not built on hierarchy but on relations of humility, respect and mutual aid.

Sources

Karoniaktajeh, The Indian Claims Commission is illegal, unjust and criminal (1965)

James Settee, An Indian camp at the mouth of Nelson River Hudson’s Bay, first published in Papers of the 8th Algonquian Conference (1977), republished in kisiskâciwan (2018)

Art Napoleon, Key terms and concepts for exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin, the Cree worldview (2014)

Harold Cardinal and Walter Hildebrandt, Treaty Elders of Saskatchewan: Our Dream Is That Our Peoples Will One Day Be Clearly Recognized as Nations (2000)

Marie Smallface-Marule, Traditional Indian Government: Of the People, by the People, for the People (1984)

Also

Oka Crisis: The legacy of the warrior flag (CBC, 2020)

Gitxsan Land Defenders’ Legal Fund

1492 Land Back Lane Legal Fund

1492 Land Back Lane official twitter account

Protect the Tract: Haldimand Tract Moratorium

Audio interview with Wade Crawford from Six Nations of the Grand River (2010)

The One-and-a-Half Men: The Story of Jim Brady and Malcolm Norris