Malcolm Norris hanging nets, ca. 1934 (Glenbow Collection)

Speech made on July 4, 1962 by Malcolm Norris at a ceremony in Batoche marking the 100th anniversary of The Royal Regiment of Canada.

The Riel Rebellion: causes, casualties, aftermath.

Acknowledgement to the Chair and dignitaries present. (CHAIRMAN Ethel Brant Monture, internationally known author, lecturer and historian. A great-great granddaughter of Chief Joseph Brant of the Six Nations.)

I am indeed greatly honored in being privileged to speak to you on this auspicious occasion, as a member of the Metis people of Saskatchewan.

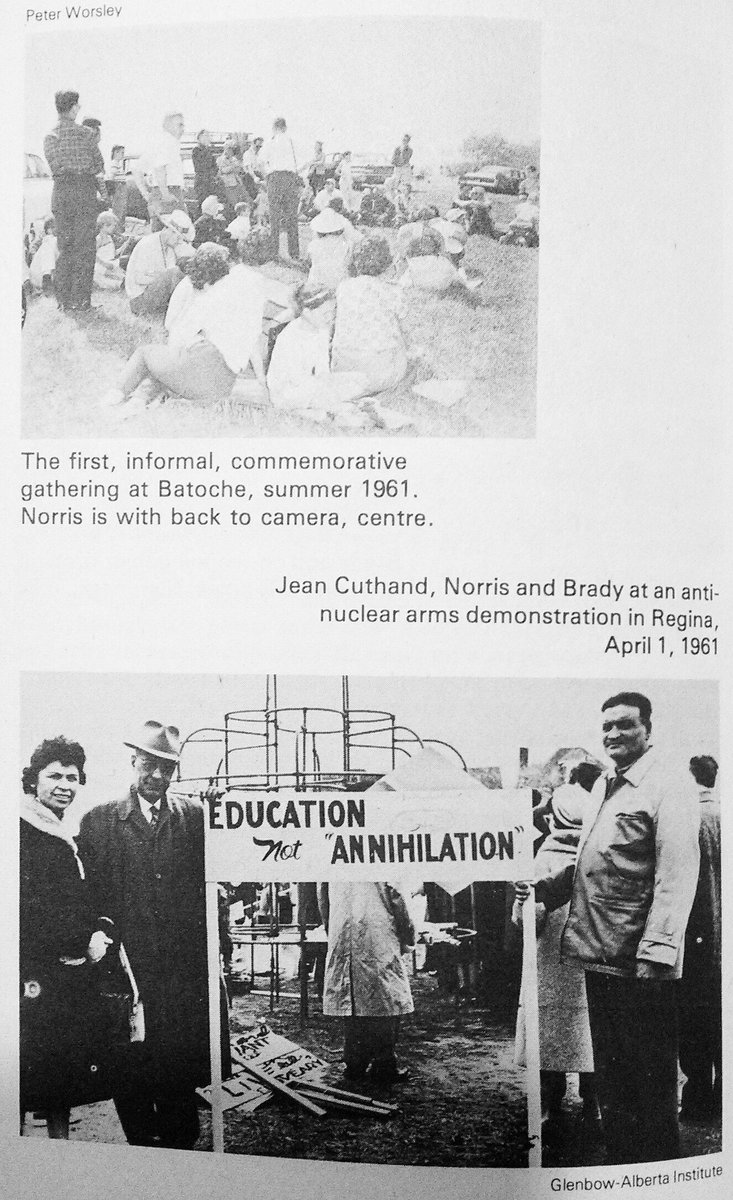

We are gathered here today on the 100th anniversary of The Royal Regiment of Canada to pay tribute and honor all those who fell in the Northwest Rebellion of 1885.

Few, if any, places on the Canadian prairies are of greater historic significance than the site upon which we are assembled today, Batoche. This is the site of the final military encounter of the uprising of the Metis people in 1885. It was a struggle of brave men on both sides.

Madam Chairman, as a representative of the Metis people, I feel we do take exception to this term “rebellion,” in the sense of rebelling against the Crown. It is unfortunate that early historians have recorded the Metis struggle for justice in this light. It is even more unfortunate that in our schools the facts of the Northwest uprising were distorted. A basic factor in the uprising was hunger, due to the disappearance of the buffalo. The threads of history are woven into the very fabric of our Canadian nationhood. I suggest you read Saskatchewan: The History of a Province by T.W. Wright, the chapter “Grievances, Guns and Gallows.”

It is only in recent years that some historians have delved into historical records and documents for that period between the years 1857 to 1885 to get at the facts.

Among those who gave their lives in those troublesome days was David Louis Riel. Riel is now regarded by many as a great Canadian patriot. As a young man of 24 years, he led the Metis and other settlers of the Red River Valley in a successful struggle for the establishment of democratic parliamentary government.

In the comparatively isolated and small Red River settlement, Riel carried on a similar battle for freedom as waged by Mackenzie and Papineau in eastern Canada in the year 1837. For these activities he was persecuted and hounded and forced into hiding (even while he was the elected parliamentary representative and the member for the Manitoba riding of Provencher) and so went into exile.

Madam Chairman, I quote from the Montreal Gazette of April 24, 1885, page 8, Column 1.

“The rebels in Manitoba had fought under Riel in 1870, for constitutional government, and today that province enjoys it and they might thank Riel for that. Riel is now fighting in the Northwest for responsible government, for the people there have no political rights and were risking their lives to get them.”

It was in the year 1870 that Riel’s former proposals for a Bill of Rights were finally incorporated under federal legislation as “The Manitoba Act.”

Another great patriot, an outstanding leader of the Metis people, is Gabriel Dumont, the great buffalo hunter. His earthly remains are interred in this very cemetery beside which we stand this afternoon. He lies here among his old neighbors, and Metis and Sioux friends who gave their lives for the “Metis cause.” May we here today hope his spirit continues.

Colonel Steele of the North West Mounted Police wrote of Gabriel as follows: “One might travel the plains from one end to the other and never hear an unkind word of Gabriel Dumont.”

When in trouble, the Metis cry was always for Gabriel. While he was admittedly illiterate, he did have a clear idea of his rights and those of his people and their needs. He had no fear, though respected the power of authority. He was a man of action. As he himself is reported to have said, “You cannot make an omelet without breaking a few eggs.”

Now may I ask, “What was the Metis cause?” Time will not permit of a lengthy dissertation; suffice to say that on this very site the prime minister of Canada, The Right Honorable John Diefenbaker, said on June 29, 1961 — just one year ago — “They (the Metis) tried to have wrongs rectified and there was injustice in the western land.”

Through their Indian mothers, the Metis possessed Indian title to their lands. Their attachment to their lands and their willingness to defend them, were of a piece with the patriotism which has inspired people everywhere to defend their homes and possessions.

There was a deplorable lack of political insight on the part of the aging Sir John A. Macdonald and the government of his day. No less than 80 petitions and other submissions were made by the Metis people, to his government between the years 1878 and 1884. Try as they would, the Metis could not get titles to their lands, while the government alienated large blocks of lands to speculators.

During this period, another great Canadian, Wilfrid Laurier (later to become prime minister of Canada), said: “Had I been born on the banks of the Saskatchewan, I myself would have shouldered a musket to fight against the neglect of governments and the shameless greed of speculation.”

With respect to land speculators, the Edmonton Bulletin of June 15, 1885 had this to say:

“That Lieutenant Governor Edgar Dewdney was not without blame in causing the Rising. He misrepresented the government to the people of the Northwest and misrepresented the people to the government. Moreover, he was a speculator in the territory he was governing.”

This, my friends, is but a partial answer to the question. “What was the Metis cause?”

I would now like to mention something about the brave men on both sides of the struggle, still referred to as the Northwest Rebellion.

History records that Major General Frederick Middleton, on March 23, 1885 was ordered by the prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, to Winnipeg. He asked for 2,000 men. Before the Rising was over, the total number of Canadians engaged (apart from the 500 Mounted Police) was 7,982 men, including transport, medical and other corps.

At the Fish Creek battle on April 24, 1885, General Middleton’s forces numbered 925 men, armed with four cannon, and at that time the latest type weapons.

Gabriel Dumont is mentioned as having 54 poorly-armed Metis — 47 men occupied rifle pits in the main ravine, whilst Dumont with 6 companions were stationed in an adjoining coulee. Casualties reported are — 10 killed and 40 wounded for Middleton’s forces and 3 killed and 2 wounded for Dumont.

“Les Anglais,” as the Metis termed the Canadian troops, were severely checked at this engagement. General Middleton retired from his position. He then waited for some three weeks for reinforcements before moving on to Batoche.

When you visit Fish Creek a few miles west of here, you will find a Historic Site cairn with these words inscribed upon a bronze metal plate:

“When General Middleton was moving to capture Batoche, his forces were attacked on the 24th of April by the half-breeds under Gabriel Dumont from concealed rifle pits near the mouth of Fish Creek. The rebels were defeated and driven from the field.”

In view of what history records, this inscription on a national monument is regarded by the Metis people of western Canada as a falsification, deliberate or otherwise.

I am happy to state, however, that consideration is being given by appropriate authorities to change the wording of this inscription on a national monument to conform to historical fact. For this, the Metis people shall be most grateful.

To you, The Royal Regiment of Canada, on behalf of the Metis people of Saskatchewan, we extend our warm welcome. May you come to love the valley of the Saskatchewan, as our people have over the years.

In conclusion, Madam Chairman, may I say that throughout the world today there are tens of millions of people who hold to a passionate desire for social justice and the right to lead decent human lives. Because of this struggle, Canada today is a great nation, but it is necessary for me to remind you that the conditions of my people and the Indians of Canada is a blot on our country. If Canada is to continue to make progress in the years ahead, it is necessary for the Canadian people and their governments to remove this blot.

To achieve peace is perhaps man’s greatest problem today. For all those who reject global suicide and related international adventures alike, the struggle against the cold war in favor of a genuine peace is the most important issue of our day.

May we hope that the accord between the Metis and Indian people and other Canadians displayed here today may spread throughout a world which must surely become one world or no world at all.

I thank you.

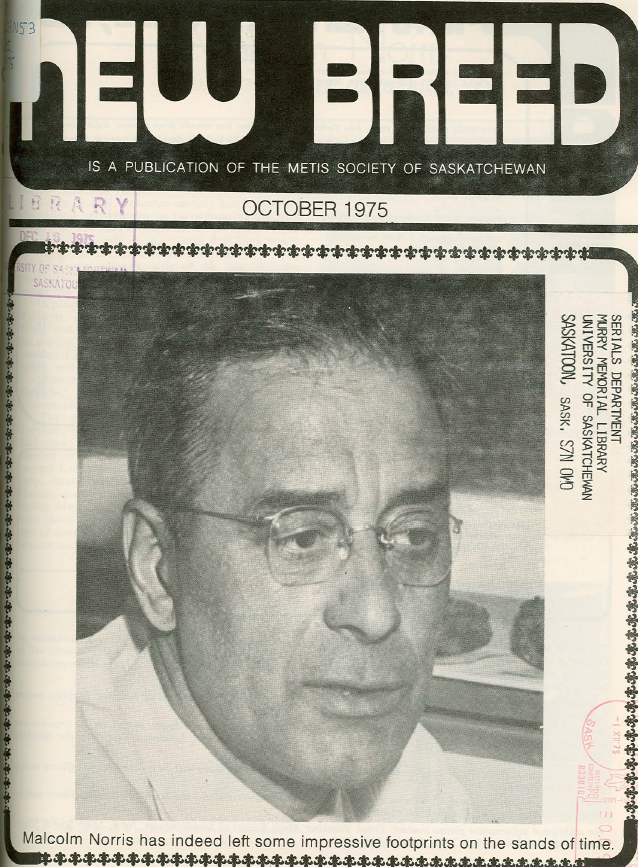

Malcolm F. Norris

July 4, 1962

(TRANSCRIBER: JOANNE GREENWOOD, SOURCE: SASK. SOUND ARCHIVES PROGRAMME)

“The Canadian Confederation is, therefore, as regards Manitoba and the North-West, a deceit.”

– Louis Riel, 1874 (Manitoba Free Press)

Also

An Appeal for Justice, by Louis Riel (1885)

A Martyr, from The Alarm (1885)

Maria Campbell’s speech to the Native Peoples Caravan in Toronto (1974)

The Form of the Struggle For Liberation, by Howard Adams (1975)

The Indian Claims Commission is illegal, unjust and criminal, by Karoniaktajeh (1965)

Overshadowed National Liberation Wars, by Howard Adams (1992)

Liberation from “That Vicious System”: Jim Brady’s 20th Century Métis Cooperatives and Colonial State Responses, by Molly Swain (2018)

A Condensed History of Canada’s Colonial Cops, by M.Gouldhawke (2020)