From ‘Freedom: A Journal of Anarchist Communism’, January 1911, London, UK

* Translated for Freedom from “Ernest Cœurderoy: Jours d’Exil,” Vol. I. (Paris: P.-V, Stock, 1910)

The tempest of February had swept away my discouragement; I had been roused by the acclamations of a free people; I breathed at ease in an atmosphere saturated with the tumult of the rising. Far, far from me had I cast the poisoned tunic that depression weaves around the shoulders of the solitary man. Breathlessly had I rushed forth towards the Star of Hope that the Revolution held alight before me. To the end of the world would I have followed that star, eager as the lover who at length beholds the betrothed of his dreams.

I who had heretofore been dumb through timidity, could now, in the clubs, through indignation find words of eloquence. For the man whose emotion is not simulated will always speak well, once the cry of his heart leaps forth to the multitude.

I knew the people; I had followed them in every manifestation of their thoughts, in each act of their life, from their deathbed in the garret to their throne on the barricade. The Revolution had restored my life; she could demand it at any moment; I was ready.

My life had become a continuous delirium, an insatiable craving for action. From that hour, by day and by night, a voice rang ceaselessly in my ears — Forward! forward!

March 17, May 15, June, 1848. Forward! We are far from the days of February. This is the 17th of March, first essay of a timid reaction, first hypocrisy of a bourgeoisie without principle to whom the Republic had temporarily confided its destinies.

Here is the 15th of May, tempest of a day, which carried off the bravest sons of Liberty, those we are accustomed to see the first within the breach. They rose in the morning in the name of the peoples’ solidarity, night will once more see them prostrate, more closely fettered than before, like to the martyred Poland they hungered to restore. All honour to you, Barbès, Blanqui, Laviron, Chancel, Raspail; your example will be followed, but too late, alas! for the Revolution.

Forward! forward! Here come gloomy days. Never since those of Spartacus has history recounted the like, nor ever will she record them save with a pen shrouded in crape and dipped in blood.

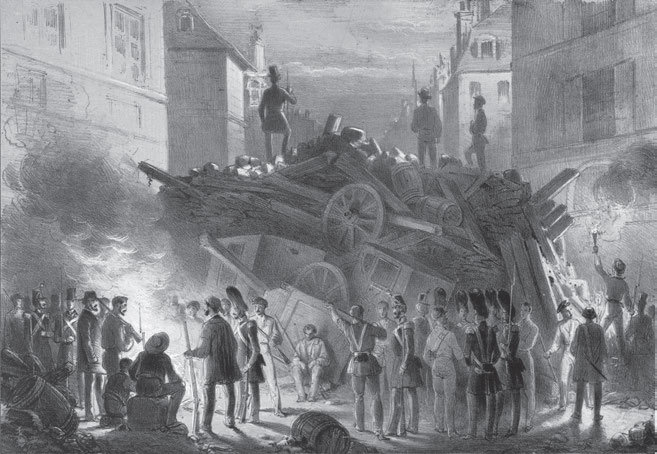

June 23, 24, 25, 1848! Never on the banks of the Seine did the warm sun rise upon more dead; never were the waters of the river crimsoned with so much blood; never were more paving-stones torn from their sandy bed; never did the sister voices of tocsin and cannon convulse the air with so clamorous a roar.

It was not an outbreak among small shopkeepers; it was a revolt of rebel angels, who since then have stirred no more. All that the proletariat of Paris contained of invincible energy, of poetic fervour, fell in those evil days, suffocated under the bourgeois reaction like wheat among tares.

They disdained the expediency of a deceitful Diplomacy, of a frigid Opportunism — these proud children of the people; they rose when called by the voice of Liberty; they halted when called by the voice of Death, which also is that of Liberty. Like their combats, their banner was stainless, their motto replete with courage.

Their banner was red. What other colour could they adopt but that of blood, that stream of life that runs through each organ in man, that not one can monopolise singly without danger of death? What else did they claim, those who do all, but their part in the consummation of the commonwealth — one drop of blood?

Their motto was simple, but wiser in its simplicity than lying systems: “Work or lead!” had they cried. The very essence of Revolution is there; it is only the people who are able to enshrine within a phrase the aspirations of a century. — Work!… that is to say, the abolition of private property, of interest, of every monopoly fatal to labour. — Or Lead!… or war against all these abuses by the swiftest means, that last argument of the oppressed.

With what did bourgeois hypocrisy confront this frank attack? — With three tags sewn together, the Tricolour, the flag of the People, the Aristocrats, and the Bourgeoisie; the standard of labour, idleness, and commerce! As though one could combine robbery with justice, misery with wealth, life with death! The Tricolour, smirched by every dishonour, the rag one saw dragged through Spain, Antwerp, Ancona, Constantine, wherever it could gather up mire! — And then these words: Order, public safety, maintenance of the Government, words still repeated by the walls of Warsaw, the banks of the Saône by Lyons, the echoes of Saint-Mery and Transnonnain — those three words with which every iniquity is upheld.

And while the people to whom work was denied hurled its challenge in the face of the world from the summit of sun-scorched barricades; while avenging bullets, piercing the crowd of functionaries, struck all that shone the most, high-priest and military chief, what were the bourgeois about?

Oh! who shall describe the precautions taken to preserve their savings? Who name their cold sweats, their agonies and sleepless nights? Who shall enumerate their betrayals, their crimes and assassinations? Who will ever know their nocturnal exploits, the number of unarmed men whose brains they scattered against the walls of their sacred churches? Who shall paint their martial demeanour when danger was past? Who repeat their Te Deums and songs of glory? Who recall their denunciations and senseless calumnies? Who delineate the tortures inflicted by their tormentors upon those unhappy ones who lay groaning in the hospitals and prisons?

Tears and disgust choke me…. I who write these lines have seen examining magistrates of a moderate Republic probing like jackals among the bleeding stumps and horrible gunshot wounds. Nor was I in a position to prevent these saturnalias!

Cowardly and degrading cruelty! Horrible filth and carnage! Oh, may that bloated bourgeoisie be for ever accursed; may the site of its shops be sown with salt and sulphur, and may the mercy of its God be light upon its greasy soul!

And yet, there are people still who believe in the revolutionary spirit of a grocer!!

Fools, fools! The carrion crow for ever follows in the wake of brilliant armies, its dismal croak drowns the blast of the bugles. The hyena always quits its den when night mantles the snow-crowned heights, when the sound of arms is silenced, when the glittering sabre returns to its scabbard, when dust once more gathers upon the bronzed gun-barrel, when the horse has broken its bridle, and its lifeless rider sleeps beneath a bush. Always, too, always will the vile bourgeois suck nourishment from the vitals of the worker; always will he exploit his labour and his struggles, his life and his death.

The question between private interests and well-being, parsimony and happiness, labour and exploitation, the Tricolour and the Red Flag — between the Bourgeoisie and the Proletariat — was thus well weighed in June, 1848. For the preservation of humanity, for the salvation of the Revolution and for our own, for the honour of those who died in June, for the sake of our forefathers, of our children, let us leave it there, and no longer seek to unite interests that are eternally incompatible.

The bourgeoisie will die, as it has lived, in final impenitence. It is not sufficiently disinterested to commit suicide; it cannot become so; it will succumb only when strangled by a superior force.

From whence will come that force? A formidable question. Alas! never again will a proletariat arise so desperate, so colossal, so glorious, so strong in principle, so certain of its programme, as that of those days of June, 1848. We need not hope for it; it was its supreme effort, and no agony lasts for five years! All that once was most alive in France now sleeps under the brown sod. We who remain no longer possess that inspiration that exhaled from their virile breasts; we lack such hearts and hands.

With her last sigh revolutionary France bequeathed the solution of the social problem to the nations; she is dead, vanquished in the throes of childbirth. Others must rear the child of her hopes. France died at the Revolution. Her star, which once blazed from the zenith, has sunk to the earth with those of the nations whom age overtook.

Cease to cast eyes of hope towards the West, O People. Ye wise men of Europe who await a new Messiah, it is from the East he will come; for it is in the countries where the sun rises that religions, prophets, and peoples are born.

Revolutionary Socialists, it is childish to dim our eyes weeping for the dead! Leave it to the demagogues to have masses sung for the repose of their souls! Once again I suggest the Cossacks for the salvation of society, for I conceive no Revolution to be possible except during a general war. And Russia alone can force this upon old Europe.

A sacrilege — let my invocation be one!…. My voice for freedom never leant upon any power in heaven or on earth. Am I wrong if, born in this century of our decadence, I dare to tell all that I foresee?

Ernest Cœurderoy – Max Nettlau (1910)

From ‘Freedom: A Journal of Anarchist Communism’, November 1910, London, UK

Ernest Cœurderoy: Œuvres, Tome I., “Jours d’Exil” (Days of Exile), première partie, 1840-81. Paris P. V. Stock, éditeur, 165, rue Saint-Honoré. 3fr. 50c. Tomes II. and III. in preparation.

The literary output of present-day Anarchist writers is so large that it requires some knowledge of the history of Anarchism to understand how extremely small in numbers and isolated Anarchist authors were fifty or sixty years ago, and how welcome the rediscovery of these forgotten forerunners is to those who have enough leisure for historical studies. But scarcity alone cannot create a general interest in an author; if, however, such an early writer turns out to be a hidden mine of bold and generous ideas, expressed with artistic beauty and an unusual depth and energy of feeling, he can well claim anew the attention of modern readers, and from such reasons Cœurderoy’s principal work is now published in a full reprint of the original French text (1854-55), preceded by a biography and the author’s only known portrait.

Cœurderoy’s name, though occurring in Benoit Malon’s books, in the “Bibliographie de l’Anarchie,” and in the literary supplement of the Révolte, is so little known that the question will be raised: why has this author, who brought out six Anarchist publications from 1852 to 1855, been hardly taken notice of by his contemporaries in the “fifties” and why was he ignored by the Anarchist movement beginning in the later “sixties,” which, in unbroken continuation, is the basis and origin of the present movement in all countries?

Cœurderoy, a French political refugee of 1849, had raised his voice against authority under all its forms, including the Republican and Socialist authorities among the proscripts of his time; hence his writings fell under the great ban of all parties, and he had to lead the life of “an exile within exile.” He did not care to attract followers, but he knew that a time would come when his ideas would be appreciated, and I think this time has come. He had to leave one country after the other, from 1849 to 1855, and after this year he disappears even from our notice until the time of his tragical death in 1862. Add to this that what remained of his scattered writings was stored away, and finally burned by his own mother.

The result is that of his six separate publications only about 55 copies in all are known to exist today. They were remembered by a few broader minded Socialists of the “fifties”, who might have recalled their existence to the new generation at the time of the International, but somehow they did not do this. Neither Talandier, nor Herzen, nor Elie Reclus appear to have mentioned Cœurderoy to Bakunin, when he returned from prison and exile. It is true Cœurderoy was near his death then, in 1863, and Bakunin called for living energies, and had no time to spare on literary reminiscences. To some of us, however, who candidly admit that they are not always carried away headlong by revolutionary impulse, and that they can spare time for a good book, these works will be a source of intellectual and artistic pleasure.

Ernest Cœurderoy, the last of an ancient family of Burgundy, born in 1825 in Avallon, and brought up at Tonnerre (Yonne), the son of a doctor of Republican ideas, studied medicine in Paris, and, to finish his studies, became after 1846 house surgeon in several of the largest Paris hospitals, which meant hard work for the young lover of Nature and outdoor sport. Coercive education and the daily contact with the exhausted poor, whose last stage of martyrdom was the hospital, roused his feelings of revolt, but also depressed him terribly.

The revolution of February, 1848, at last gave him new life and hope. He spoke in the clubs, came to the front in the students’ movement (Comité des Ecoles), and was elected to the large committee of some two hundred Democrats and Socialists, who selected the advanced candidates for the Paris elections, and were the centre of resistance against the reactionary forces in power after the June massacre of the proletariat.

Cœurderoy at that time attended the wounded and dying insurgents in the central popular hospital, the Hotel Dieu, and had to defend them against the inquisitive magistrates and police, who hovered round to spy and disturb the last moments of the dying. From this time certainly dates his absolute horror and hatred of the State, Government, and all its tools, and of the bourgeois class who alone profit by the existing system. He became a member of the inner circle of twenty-five, chosen from the large committee mentioned, but soon gave in his resignation, because, in the pledge to defend the Constitution (meaning the Republic against the reactionary attacks) which candidates, nominated by the committees had to sign, the words “by armed force” were cautiously omitted. He was again elected one of the twenty-five, and this time a great task fell to this committee.

Louis Bonaparte, the president, in disregard of the Constitution, sent troops to crush the Roman Republic which Mazzini, one of its triumvirs, and Garibaldi defended. The Montagne, the Parliamentary party led by Ledru Rollin, protested, and the committee of the twenty-five, mostly young Socialists and Radicals, did their best to make this protest take the form of revolutionary action. June 13, 1849, when the crisis took place, was a defeat of the revolutionary forces; from that day Cœurderoy was an outlaw. He escaped to Switzerland, and was, in his absence, sentenced to transportation for life.

For a time he settled in Lausanne, where he practised as a doctor; but early in 1851 he and sixteen other refugees were expelled from Switzerland for boldly claiming the right of asylum, not as charity but as a Republican right. Cœurderoy had also to leave Belgium immediately, and went to London (April, 1851), where he stayed for about two years. His contributions to papers from 1849 to 1851 are remarkable for their absence of party spirit, and the sincere desire of the author to help to make all advanced parties co-operate against Louis Bonaparte, who slowly prepared his dastardly plot to strangle the Republic. This he achieved on December 2, 1861.

From this date the Republican and Socialist leaders and their followers were powerless, and Cœurderoy felt that, in discussing the causes of their discomfiture, he was no longer impairing the chances of a battle which was already lost. He was so naïve as to think that discussion would be welcome, but it never is. He began to write his first book, “De la Révolution dans L’Homme et dans le Societé” (Revolution in Man and in Society), Brussels, 1852 (September), a comparison of the human body and society, showing the continual evolution and transformation of either, arriving at the conclusion that revolution is an inevitable and permanently recurring social phenomenon.

But the follies and pretensions of all the exiled statesmen and leaders of 1848, 1849, 1851, were too much for Cœurderoy’s sense of humour and his intense feeling of the greatness of the cause so poorly served by these small men. He and Octave Vauthier published, in June, 1832, “La Barrière du Combat,” a pamphlet which played havoc with the stern leadership of Ledru Rollin and Louis Blanc, Cabet, and Leroux, Mazzini and others. From that time Cœurderoy was proscribed. He said many things more in the concluding parts of his book, “De la Révolution,” but, besides slander behind his back, ostracism of the most intolerant kind was the only reply made to him. He continued to study and to write, and worked his ideas into the many chapters of personal impressions which form the “Jours d’Exil.”

He left London, where he felt very unhappy, for the glorious sun of Spain, which revived him (1853-54). Thence he travelled to London to have the first part of “Jours d’Exil” published (spring of 1854); back to Spain, where he wrote the letters reprinted as “Trois Lettres au journal L’Homme” (of Jersey), London, 1854 (summer); and in October of that year he published the book, “Hurrah!! on in Révolution par les Cosaques” (Hurrah!! or Revolution by Cossacks).

For his utter despair of the power of the proletariat to recuperate strength after the massacre of June 1848, made him cry for Russian invasion, a universal war, and a general breakdown of Western civilisation; he called upon the Cossacks as brute forces of destruction par excellence, having full confidence that by the action of free and conscious individuals, Anarchists in one word, freedom would arise like a phoenix out of the smouldering ruins of the Old World. He intended to sketch this evolution in a book to be called “Les Braconniers ou la Révolution par l’Individu” (The Poachers, or Revolution by the Individual); these works on social demolition were to be followed by a description of Socialist Reconstruction. The latter two books were never written or were destroyed, in all his manuscripts seem to have been.

Cœurderoy’s health declined in 1854; he went to Italy and spent a winter of frightful suffering in Turin. Revived by beautiful spring days spent at Annecy in Savoy, with its picturesque lake, he married in June, 1855, at Geneva and returned to Annecy. In July he was expelled from Savoy and Piedmont, and it is not known where he passed the years following. His last chapter of “Jours d’Exil,” second part, was written in November, 1855; the book itself (which will form Tomes II. and III, of our reprint) bears the date: London, December, 1855.

In 1859, by a curt letter, Cœurderoy scorned Bonaparte’s amnesty; in 1862 he settled in a small village in the neighbourhood of Geneva, where in October, 1862, he cut his veins and died. Some will say that he had lost, or was then losing, his mental faculties. To me, this remains a problem and a question to be discussed in a larger biography. His great productivity from 1852 to 1855, followed by years of absolute silence, 1856 to 1862, is another problem which I am unable to solve as yet.

What, then, are his principal ideas? Who can condense fifteen hundred pages, sparkling with ideas poetically expressed, into the compass of a few words? It is sufficient to say that he looks at a great variety of subjects taken from Nature, social and political life, history, morals and habits, etc., with the eyes of a sincere Anarchist of the largest mind possible. At his time, Anarchism was freedom one and indivisible, and no economic qualifications, Communist or Individualist, cut it into sections, an exclusiveness which he would not have accepted, he who dreamed of still higher perfection, still loftier flights of freedom.

Was he, then, some might guess, an Individualist? Yes and no. He was as truly a Socialist (Collectivist, I should say, though he would not have excluded Communism) as anybody ever was, but he was also a rebel against each state of things where the individual would not enjoy the fullest freedom in every sense. He aimed at the continuous improvement of all collective arrangements by making them subject to the freedom of the individual as the first condition of their right to exist, which, I take it, we are all aiming at, by freely discussing our ideas.

The “Jours d’Exil,” first part, contains, among others, Cœurderoy’s impressions of Paris in 1848-49, the death of Laviron (who fought for the Romans against the French), the story of the flight to Switzerland with the aid of a smuggler, the refugees’ life at Geneva, spies in political movements, impressions of Alpine scenery and the heroic age of Swiss history, a striking chapter on the execution of Montcharmont, with an examination of the right to judge others, the radical students’ society at Lausanne, etc.

On the contents of Tomes II. and III. of the present edition I may speak another time. Each volume can be read separately.

November 1.

M. N.

Also

Hurrah!!! for Ernest Cœurderoy, at the Libertarian Labyrinth

War is Declared!, by Joseph Déjacque (1859)

A Page in the History of Civilization, by F. Girard (1860)

Anarchy and Communism, by Le Drapeau Noir (1883)

The Eighteenth of March, by Louise Michel (1896)

On the Riot, by Library of Riots (1990)