[Note that the content of this article includes graphic descriptions of violence against Indigenous persons and racist terminology. -Ed.]

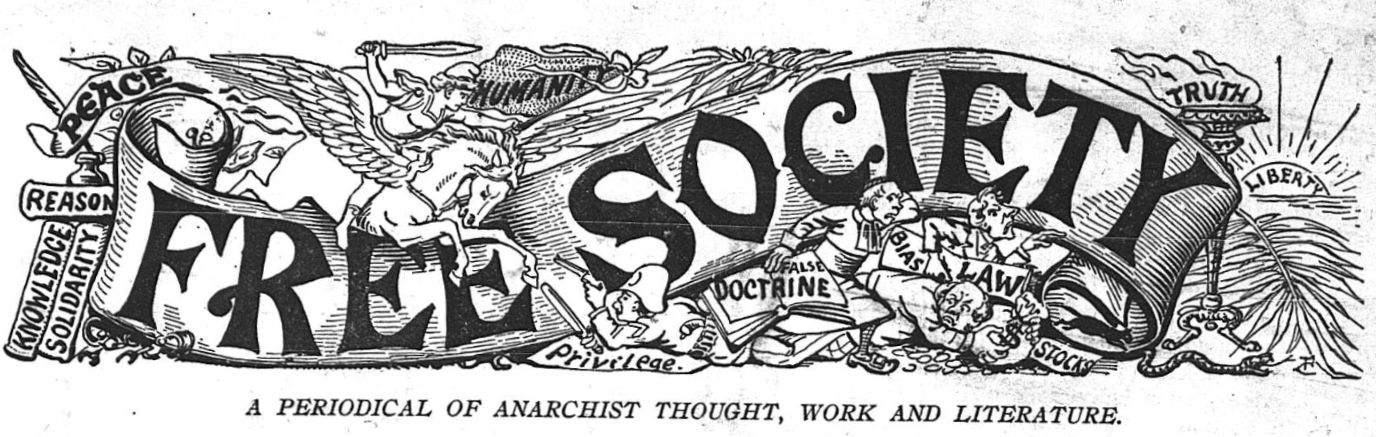

From ‘Free Society: A Periodical of Anarchist Thought, Work, and Literature’, March 9, 1902, Chicago

Is civilization the result of a particular fashion in clothing, and style of wearing hair? It has been stated that the late order of the interior department, forbidding Indians to wear long hair, blankets, paint the face, have dances, feasts, etc., was made in the interest of civilization. The recent discussions in congress with regard to the savagery and atrocity charged against United States soldiers in the Philippines, did not, as far as I know, touch upon soldiers’ apparel. Will any one imagine these soldiers were robed in blankets? Or that their deeds were any less revolting because the perpetrators were clad in the regulation murder garb of the nation?

Until the United States government shall cease the manufacture of special brands of costumes for its professional destroyers of human life, until it shall cease to engage in bloody, murderous warfare, this meddlesome and invasive interference with the national habits of dress, and social customs of another people, must be regarded by all persons of integrity as purely an affectation on the part of government.

While endeavoring apparently to put the aboriginal people in duress for the avowed purpose of civilizing them, this government is engaged in manufacturing savages thru military processes, by hundreds of thousands, and these of a most malignant and fiendish type. Ample testimony in support of this position is furnished by any war — by all wars. I will cite only one instance, which occurred during the late Indian troubles, to illustrate this principle. It is given in a letter printed in the New York Tribune, 1878, and reproduced in 1880 in appendix to “A Century of Dishonor” by Mrs. H. H. Jackson. Extracts from this letter here follow:

In June, 1864, Governor Evans, of Colorado, sent out a circular to the Indians of the Plains, inviting all friendly Indians to come into the neighborhood of the forts, and be protected by the United States troops. Hostilities and depredations had been committed by some bands of Indians, and the government was about to make war upon them….

“Friendly Arapahoes and Cheyennes belonging on the Arkansas River will go to Major Colby, United States agent of Fort Lyon, who will give them provisions and show them a place of safety.”

In consequence of this proclamation of the governor, a band of Cheyennes, several hundred in number, came in and settled down near Fort Lyon. After a time they were requested to remove to Sand Creek, about forty miles from Fort Lyon, when they were still guaranteed “perfect safety” and the protection of government. Rations of food were issued to them from time to time.

On November 27, Col. J. M. Chivington, a member of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Denver, and colonel of the First Colorado Cavalry, led his regiment by a forced march to Fort Lyon, induced some of the United troops to join him, and fell upon this camp of friendly Indians at daybreak.

The chief, White Antelope, always known as friendly to the whites, came running toward the soldiers, holding up his hands and crying, “Stop! Stop!” in English. When he saw there was no mistake, that it was a deliberate attack, he folded his arms and waited till he was shot down. The United States flag was floating over the lodge of Black Kettle, the head chief of the tribe; below it was tied also a small white flag as an additional security — a precaution Black Kettle had been advised by U.S. State officers to take if he met troops on the plains.

In Major Wincoop’s testimony, given before the committee appointed by congress to investigate this massacre, is the following passage: “Women and children were killed and scalped, children at their mothers’ breasts, and all the bodies mutilated in the most horrible manner….. The dead bodies of females profaned in such a manner that the recital is sickening. Col. Chivington all the time inciting his troops to their diabolical outrages.”

Another man testified to what he saw on November 30, three days after the battle, as follows: “I saw a man dismount from his horse and cut the ear from the body of a dead Indian, and the scalp from the head of another…. I saw several of the Third Regiment cut off fingers to get rings off them. I saw Major Layre scalp a dead Indian.”…

Robert Bent testifies: “I saw one squaw lying on the bank, whose leg had been broken. A soldier came up to her with a drawn sabre. She raised her arm to protect herself; he struck, breaking her arm. She rolled over and raised her other arm; he struck, breaking that, and then left her without killing her. I saw one squaw cut open, and an unborn child lying by her side.”

When this Colorado regiment of demons returned to Denver they were greeted with an ovation. The Denver News said: “All acquitted themselves well. Colorado soldiers have again covered themselves with glory”; and at a theatrical performance given in the city, these scalps taken from Indians were held up and exhibited to the audience, which applauded rapturously.

After listening, day after day, to such testimonies as these I have quoted, and others so much worse that I may not write and The Tribune could not print the words needful to tell them, the committee reported: “It is difficult to believe that beings in the form of men, and disgracing the uniform of United States soldiers and officers, could commit or countenance the commission of such acts of cruelty and barbarity.”

And of Col, Chivington: “He deliberately planned and executed a foul and dastardly massacre, which would have disgraced the veriest savage among those who were the victims of his cruelty.”

Emily G. Taylor

Chicago, Ill.

Also

Our New Medicine Man, by Emily G. Taylor (1902)

Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native, by Patrick Wolfe (2006)

Civilization vs Solidarity: Louise Michel and the Kanaks, by Carolyn J. Eichner (2017)

Race in a Godless World, by Nathan Alexander (2019)

Unknowable: Against an Indigenous Anarchist Theory, by Klee Benally, Ya’iishjááshch’ilí (2021)

Untenable History, by Carolyn Nakamura (2022)

May Day and Colonialism, by K. C. Sinclair (2025)

Sand Creek Massacre, from the National Park Service

Philippine–American War, from Wikipedia