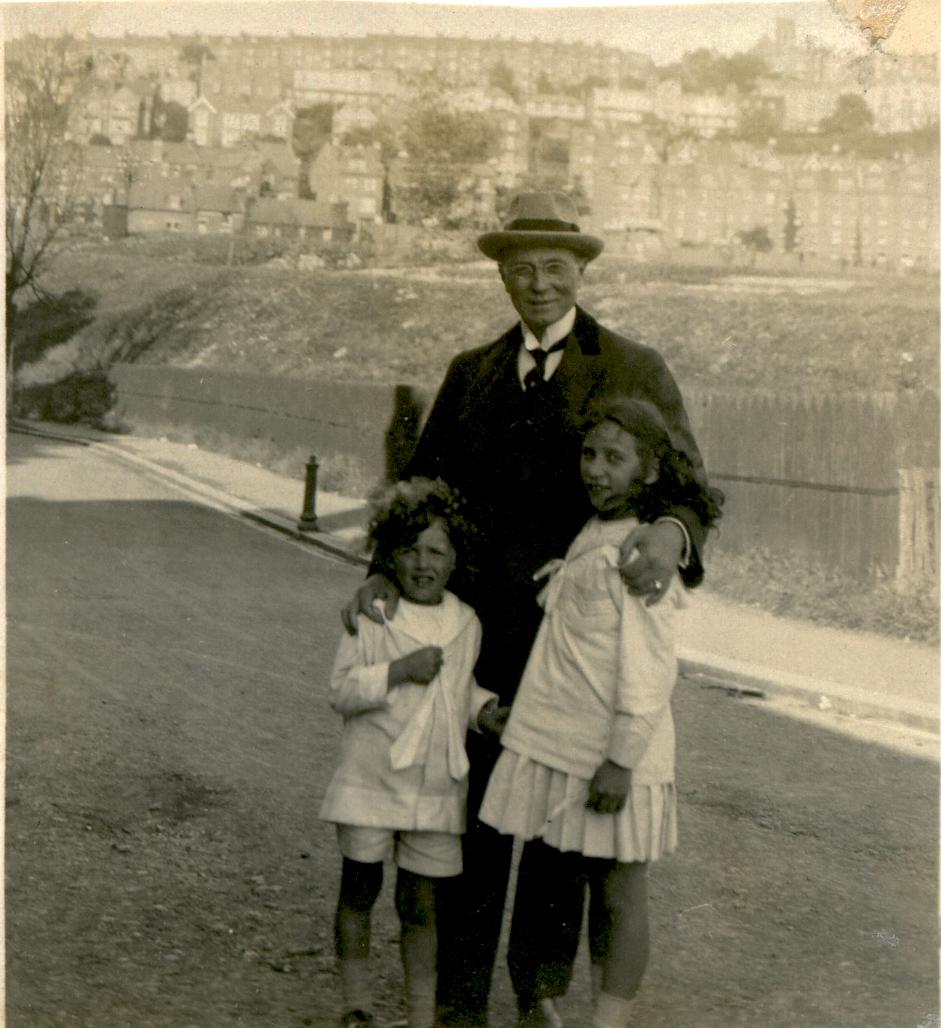

Emidio Recchioni with his children, Vernon Richards (Vero) and Vera

Between Ourselves

Where We Have Failed and How We Might Succeed

From ‘Freedom: A Journal of Anarchist Communism’, September 1915, London, UK

The war which still rages, devastating the world, is teaching many a lesson of which we Anarchists ought to take advantage in carrying on our struggle against Privilege.

When this orgy of carnage began, the Anarchists, in contrast with the well-to-do classes who feigned a holy horror of the war which had been provoked by themselves, did not exhibit or feel any surprise, having always considered war a normal condition in a society based on economic and political antagonism. What they rather felt was disappointment (of short duration, however) on seeing how easily the masses were persuaded to answer the call to arms made by the various Governments. Anarchists had in fact been dreaming that their propaganda of so many years must have taught the working classes not to place themselves in the hands of the State, at least to the extent of being pushed into a war against one another.

Of course, the Anarchists were far from believing that the workers were ready to make a revolution; but they thought they would have made such a stand as to impress upon the responsible powers that they were playing a dangerous game. It was not so. It sufficed for the rulers, in co-operation with an unscrupulous Press and a few renegade revolutionists, to proclaim that the war was necessary to save the soil of the various “Fatherlands” from invasion or to safeguard the rights and principles of nationality, civilisation, etc., to arouse the old patriotic prejudices and, above all, the reverence for the State, stifling other sentiments such as working-class solidarity; and the masses allowed themselves still as ever a flock of sheep-to be led, with scarcely a protest, to the horrible slaughter.

But after the first disappointment we had to acknowledge that the responsibility for the recrudescence of such prejudices among the workers rested with the forward parties, which had failed, in spite of fifty years of propaganda, to forge a weapon with which to combat the deleterious influence of the reactionary elements of society. Consider, for instance, the tactics of the Socialists in Germany, England, France, and Italy — all over Europe, in fact — and you cannot help thinking that they are responsible for the lack of resistance on the part of the working classes when the various Governments ordered mobilisation. For over fifty years the official Socialist parties had taught the workers that to bring about the revolution which should change the present society into the one dreamt of by all sections of Socialists (Anarchists included) it was necessary first to get hold of the public powers by Parliamentary means, which, of course, meant collaboration with the classes and political powers which they claim to intend to overthrow. What could be expected from ironbound organisations formed merely for the purpose of obtaining seats in Parliament, which implies the surrender of free initiative to political representatives, which, in time, turns the people into a collection of automatons by checking their spirit of revolt?

It has been said that in Germany the people threw in their lot with the Government because they believed in the news that the “barbarian Russian” had invaded the Fatherland. Granted that was so, and that it formed an excuse for participation in the war, it still does not justify the tactics which had fostered the patriotic spirit instead of changing that spirit into the sentiment of international solidarity. In fact, the majority of the German Social Democracy has for years preached, and, continues to preach, that the destiny of the German working class is bound up with the development of German industry.

Anarchists have pointed out all this since they severed connection with the Socialists. As a matter of fact, it was on account of the authoritarian tactics of the Socialists that Anarchists have taken an opposite path, pointing out that mechanical conceptions of discipline would create a spirit of submission and passivity, and sap the source of action among the workers.

In spite of the opposition of the Socialist parties which expelled the “mad” Anarchists from their congresses, and in spite of persecution by the Governments, Anarchists tried to spread their ideal amongst the people by individual or collective action. But their efforts were isolated and not followed by any important work of co-ordination among the people. For years, indeed, we seemed to disdain contact with the masses: we preached our ideal of their redemption, but failed to lead their daily life, to take an interest in their immediate economic claims, though such contact with them would have enabled us to permeate them with our ideals. In fact, Syndicalism should be the rock on which we should build Anarchism. If Syndicalism has not yet come up to our expectations, it is just because we have failed to vivify it with our idealism. Instead, we left this work of permeation to the Socialists, and the Socialists transformed the workers into a flock of electors.

We Anarchists have called ourselves atheists, but what have we done to uproot religious sentiments among the peasantry? We have called ourselves anti-militarists and anti-Parliamentarians, but what have we done anti-militaristic or anti-Parliamentarian in all these years, with the exception of a few manifestoes and pamphlets? We are against the State, and the State continues to control everything — the shaping, in the schools, of the minds of the young into a condition of submission and respect for the very institutions (property, law, police, army, and magistracy) which we intend to overthrow. We have spoken and written continually more for the initiated than for the masses, and have wasted in philosophic and scientific disquisitions, which nobody understands, time which we should have devoted to carrying our voice and our action amongst the industrial workers and the peasantry, in order, to uproot the prejudices on which the ruling classes worked and on which they reckoned when they declared war — a declaration which consequently found us unprepared and powerless.

And now, in France the Anarchists have either taken part openly in the “sacred union” of all parties to defend the “patrie” and the Republican institutions, or have retired into a corner, saying they are powerless to do anything — not even an individual deed of revolt.

In Italy, for nine months the Anarchists had declared themselves against the war, and two or three weekly papers wrote, and wrote again, against militarism, patriotism, nationalism, etc. Our comrades also took part in some public meetings against the war, but for lack of organisation were unable to prevent it. Yet years ago the Anarchists were tearing up the rails to prevent trains taking soldiers to the Abyssinian campaign.

But what is the use of complaining now that the mischief is done, or, rather, now that we have failed to do any mischief? Well, my remarks, especially those concerning my own comrades (which, of course, concern my humble self, too) are intended to draw attention to the errors of the past in order to avoid them in our future action.

We cannot give up our aspirations towards freedom; we cannot forget our love for those who have suffered under the tyranny of privilege — although at times, in this grey hour of discomfort there may come a fleeting thought of the vanity of our efforts; we cannot renounce the ideal of justice which nurtured us in our younger days; nor can we abandon our brothers who, under the spell of old and inherited prejudices, are fighting in a cause which is not theirs. While the storm lasts we must see to our weapons in preparation for the fight which is truly ours.

I will not prophesy what will happen after the war, nor how it will end; but if I cannot say who will be the winners, I can easily point out the losers — the people. They will lose not only in the sense of the lives sacrificed to the militaristic Moloch, and from the material misery which will follow the tragic event, but also — and above all — from the added prestige which in all countries the State will have gained; and our task will be harder than ever.

We must, therefore, unite all our efforts in forming the new consciousness of the masses, not neglecting any means which may lead to success without going contrary to our revolutionary method. If it is found necessary to co-operate with other sections of the revolutionists, we must do it without perpetually being afraid of being inconsistent.

From all parts come signs which indicate that even the very Socialists who were for war, voting the war credits and collaborating with their Governments, are coming to their senses. From Russia, Poland, Bulgaria, Roumania, and Servia come voices of the possibility of peace and of adherence to the old principles of international solidarity. The German Social Democratic Party of Austria has just issued a manifesto to the working classes expressing the “hope, growing from day to day, to see the war over,” and ” the members of the International, purified by experience, using all their power in the service of peace.” But what is more impressive than all is the repentance of some of the best-known leaders of German Social Democracy, on whom there seems to have dawned a new light. The same thing is. occurring in France.

This scission is being accentuated every day, and a great division in the Socialist parties of Europe, as well as in the working-class organisations, is inevitable. On the one side there will be those who will advocate the continuation of the “sacred union” with the Liberal and Democratic parties and with the State. There will be a Radical party of reform in Germany, and so in France, and in Italy especially, where to this new party there will join Republicans, Reformist Socialists, and some Syndicalists. On the other hand, there will be those who will. continue to fight Capitalism on the old basis of the lutte de classe, or” class-consciousness”; but as their Parliamentary and legal action has proved a failure now more than ever, they will (together with the trade organisations, which will in all countries turn to revolutionary Syndicalism, if we act quickly), if they are really bona fide, change towards direct action their line in their struggle, that is, towards the Anarchist method, the very method they have for many years opposed.

Well, if the Socialists who have at heart the interests of the working classes, recognising at last the fallacy of the old method, will abandon Parliamentary action, and will approach us, we Anarchists must in our turn lean towards them, and join hands in all those agitations which create a spirit of revolt amongst the working classes. Many occasions suitable for combined action will occur to readers of this article. Why, for instance, should we not unite in agitations for conquering freedom of speech and public meeting, and liberty of the Press, which are not yet our heritage? It is easy to foretell, for instance, that after the war many things that have been promised by the Governments to lure the people to war will remain dead letters. Then the expenditure made by the Governments will cause such a state of utter misery among the workers as to give rise to reflections which have never yet occurred to them. Then, too, the war, while it will have made large fortunes for those engaged in “high finance,” will have created a new class — small capitalists (manufacturers, merchants, and shopkeepers) ruined and reduced to proletarians. In co-operation with the Socialists just mentioned, can we not explain to these sufferers from the war the interest they have in collaborating with us to change the present form of society?

Would not an agitation against armaments have a chance of success when, the war fever having subsided, the working classes come to see that they have fought for abstractions and interests which are not theirs? There is, indeed, something quite definite which we might do in this direction. In Italy, it is rumoured that a Steel Trust press is to be formed to check, with its influence, the anti-militaristic and anti-armament propaganda from the revolutionary parties which one may foresee as soon as the war is over. Why should we not try to start a movement all over Europe in conjunction with the Socialists and Syndicalists, to propagate among the workers’ organisations the idea of boycotting the manufacture of armaments and munitions?

We could set on foot these and many other agitations, the idea of which, now briefly formulated, I leave to comrades to develop. But if it should not be possible to come to an understanding with the Socialists and Syndicalists, and the latter should choose to collaborate with the State and the Liberal and Democratic parties, as they do now under the spell of patriotic and nationalistic ideology, the Anarchists must by all means do the work themselves, and save the proletariat and workers’ organisations from such renegades. In doing so, and studying between ourselves the various points to which I have alluded, we shall be able to take advantage of the opportunity which will very soon present itself of reconstituting on a libertarian basis the Working-Class International.

E. Recchioni

Also

The story of ‘King Bomba’ – Emidio Recchioni (1864-1934), by Stuart Christie (2012)