From ‘War Commentary: For Anarchism’, Mid-August 1942, London, UK

The word ‘proletarian’ derives from the Latin proletarius, which meant literally one of the lowest order of freeman whose only use to the Roman state was to beget offspring (proles) to serve in its legions. When the word appears, somewhat rarely, in seventeenth century English literature, it retains the same general reference to the poorest classes and is used frequently in a derogatory sense to mean common or vulgar, as in Butler’s Hudibras — ‘Low proletarian tything-men’.

In the nineteenth century, with the appearance of working class revolutionary movements, the word came to have what we can regard as its more or less exact modern meaning, i.e., the wage earners of all degrees and all kinds whether industrial or agricultural. Later there arose a restricted and inexact application to the industrial wage earners, the workers in the large aggregations of capitalist industry. This is the sense in which it seems to be used most frequently nowadays, so that when we hear a Marxist talking of the proletariat, we understand the word in this narrow definition. For the purposes of this article, I shall use this inexact but general sense.

It is a prevalent theory among various schools of Marxists that the revolution can only be achieved through the agency of the industrial proletariat, whose advanced social consciousness makes them alone fitted to lead the revolting workers. Whether Marx himself actually stated this, has been the subject of considerable discussion among his followers. And it is indeed difficult to find any explicit statement among his involved and circumlocutory periods. But it does seem probable that he held some such theory, for he maintained that the revolution would come via the concentration of capital, which would result in the erection of vast amalgamated monopoly organisations of industry, whose increasing oppression of the workers would eventually provoke them to revolt. This conclusion is stated somewhat vaguely towards the end of Volume 1 of Das Kapital:

‘Along with the constantly diminishing number of the magnates of capital, who usurp and monopolise all advantages of this process of transformation, grows the mass of misery, oppression, slavery, degradation, exploitation; but with this too grows the revolt of the working class, a class always increasing in numbers, and disciplined, united, organised by the very mechanism of the process of capitalist production itself. The monopoly of capital becomes a fetter upon the mode of production, which has sprung up and flourished along with, and under it. Centralisation of the means of production and socialisation of labour at last reach a point where they become incompatible with their capitalist integument. This integument is burst asunder. The knell of private property sounds. The expropriators are expropriated.’

Such statements as this, together with Marx’s various declarations that each country must go through an industrial phase before the revolution is achieved, and his verbal participation in nationalist wars on the side of the more highly industrialised countries (on the ground that they had progressed further towards the revolution), make it appear probable that he would have agreed to a theory that the revolution must be led by the industrial workers.

Over against this must be put the fact that towards the end of his life Marx wavered over the question of the necessity for a high degree of industrialisation before the revolution can be achieved. The publication of a translation of Das Kapital in St. Petersburg pleased him so much that he began to look favourably on Russia, then the greatest European peasant country. He does not seem to have reached any definite conclusions about Russia, but there is extant a letter written to a Russian girl, Vera Zasulich, in which he said, very evasively, that his statement in Das Kapital that each country must pass through a state of intensive industrial capitalism referred only to those countries whose economic structures had been built on ‘private property, based on individual labour’. Russia, whose traditional peasant economy was based on primitive communism, might pass to a revolutionary society without having to undergo a period of capitalism. This is an embarrassing document for those who would justify, on a Marxist basis, the establishment of an industrial neo-capitalism in Russia as a prelude to the ‘communist’ society. But it is perhaps unfair to introduce Marx when we discuss the opinions of Marxists. For Marx himself stated, ‘All I know is that I myself am not a Marxist’. And he certainly seems at one time or another to have denied every theory that has been attributed to him. It would seem as if his well-known malicious humour led him to turn his doctrines into a maze of ambiguities and contradictions in which his future followers would blunder to the most ridiculous conclusions.

Whether or not Marx did assert it, the fact remains that Marxists have, for the most part, maintained this Messianic role for the industrial proletariat, and have, in practice, neglected peasants and farm workers generally, as well as other workers not employed in the large industrial aggregations. We will leave aside the question of whether the communists really mean the proletariat, when they mention them as a leading class, or whether this Protean word has yet another meaning, and must be taken as applying to the scurf of shyster lawyers, eccentric deans, popularising scientists, minor scholars, lesser trade union officials and party bureaucrats who form the leading junta of the party organisation. Instead we will give some attention to the nature of the industrial proletariat, particularly as it exists in industrial countries.

Here I would disclaim any desire to create a mythical monster called ‘a proletarian’. Too many revolutionaries carry about a sort of ventriloquial dummy which they call ‘a worker’ and which bears as little resemblance to any individual worker as the unicorn does to any creature in nature. In the words of Edward Bernstein ‘We have to take working men as they are. And they are neither so universally paupers as was set out in the Communist Manifesto, nor so free from prejudices and weakness as their courtiers wish to make us believe’ . . . General statements about workers are as inexact as most generalisations. Usually they approach no nearer to the truth than the Unicorn to his zoological prototype, the rhinoceros.

Workers are first and foremost individuals, men with their own personalities and characteristics. It is in this sense, as individuals rather than as classes, that they are of interest to anarchists. The anarchist teaching appeals to the man rather than the mass. But men do become classes and masses when and insofar as they undergo a common reaction to common circumstances. And if we are to end classes, if we are to break up masses into individuals acting in the co-operation of free men, we must at least form some general idea, as exact as possible, of the common attributes of the proletariat.

For the last hundred years the English industrial workers have been subjected to a progressive conditioning administered by the most capable ruling class in history. By a clever application of a series of minor concessions the activities of the workers were turned away from the revolutionary trends of the 1830’s to the reformism of the New Model Trade Unions. Workers’ organisations were, by the corruption of their leaders, turned into instruments for assisting class rule, until, to-day, the trades unions have been incorporated in the totalitarian state machine and the leaders of the party built on the workers’ efforts and cash, act the most brutal parts in a reactionary government. By means of universal state education, the press, the radio, the cinema, the workers have been doped into an ignorance of social truths and a general mental unawareness far greater than that of their illiterate ancestors of Owen’s day.

By the granting, in easy stages and over a number of years, of universal suffrage, the workers have been encouraged in the illusion of political equality, the illusion that the possession of the vote gives them a say in the government of the country. The Jacob’s ladder of social and economic advancement has been hung continually before them, manifested in a graded caste system among workers. Every worker can become a foreman if he is sufficiently servile. Every clerk can become a manager if he is sufficiently officious and unscrupulous. In their higher-paid ranks, skilled craftsmen, foremen, engine-drivers, etc., the workers tend to become dovetailed into the petty-bourgeoisie, imitating their manner of life and acquiring their social prejudices. A very high proportion of the proletariat has been completely demoralised by these golden apples of capitalism, and is devoid of any revolutionary consciousness. Not the least appalling result of this corruption of the workers of Britain is the fact that they have lost any real sense of self-respect, any desire to develop their personalities for something better than the social and economic scrum of would-be go-getters.

While it would be ridiculous to contend that capitalism has given out its prizes to a majority of the workers, many have benefited from the exploitation of the empire, and their good fortune has given a hope to many more of their fellows. But they should keep no illusion of continued good fortune. Capitalism will not, cannot continue to offer such baits to the proletariat. English capitalism, if it survives, will have a poor time after the war. Then the English workers will begin to experience something nearer the life of their Indian comrades, on whose misery their comparative (if slight) well being has been based. As the contradictions of capitalism drive it to act for its own eventual destruction, it will turn the screw ever more and more severely on the proletariat. Only then, I am convinced, can we hope to see a revolutionary consciousness among the English proletariat.

This revolutionary consciousness, as I noted in a recent issue of ‘War Commentary’ is to be found more in countries with small industries and large peasant populations than in countries preponderantly industrial. In such countries men have not been subjected to the intensive conditioning imposed by efficient capitalism. The state, though perhaps more ruthless in theory, is in practice, less efficient and subtle in its oppression. The workers have not been subjected to the demoralisation of bourgeois standards, of social and economic advancement. For them there have been no Jacob’s ladders, no golden apples of the Hesperides. Having escaped the regimentation of great factories, of universal state education, of the giant press, they have retained their natural perceptions, their human individuality and integrity, of which the workers of Britain have lost so much. In these countries the revolution has not retreated through the ineptitude of corrupt political parties which gulled the workers into giving their support to a fatal programme of reformism and appeasement.

Quite apart from the demoralisation induced from the policy of rulers, it seems that there is an inner, fundamental demoralisation in the factory system itself, with its usual accompaniment of a life divorced from any close or lasting contact with rural life. It takes considerable strength to withstand the spiritually destructive elements in a mass life, a life of regimentation and uniformity, of division of labour carried down to the absurdities of the Ford and Bedaux systems. Such a system is in itself a prime cause of the intellectual sterility which falls like a blight over the lives of the great majority of the urban proletariat.

In this connection it is significant to note that among the workers of Britain the most emotionally live, culturally sensitive and socially conscious, are those whose circumstances of work and life bring them in some close contact with nature, or provide some form of work that allows a certain individual initiative or creativeness. Thus the miners, most of whom still live in fairly close contact with rural surroundings, are the most militant of the British workers.

It is obvious that under a society based on freedom a system of production that in itself results in mental or emotional slavery cannot be allowed to survive. In an anarchist society there will no longer be any place for men to waste their lives in the monotonous performance of a single function. Life will become many sided. Men will no longer be industrial or agricultural workers, urban or country dwellers. The barriers between town, and country, between factory and farm, between manual and intellectual work must be broken down, and men’s experience of life must be as complete and varied as nature will allow. No class of workers can lead such a society. The industrial proletariat, as such, must be eliminated along with the bourgeoisie and every other class of the old state society. The individuals who comprise it will be able to reintegrate themselves in freedom into the whole men of the new society of anarchy. In the words of Kropotkin, ‘We maintain that the ideal of society — that is, the state towards which society is already marching is a society of integrated, combined labour. A society where each individual is a producer of both manual and intellectual work; where each able-bodied human being is a worker, and where each worker works both in the field and the industrial workshops.’

As a class the proletariat has no future. When economic exploitation dies, the class of the exploited will die. Life and the future belong to no class, but to mankind.

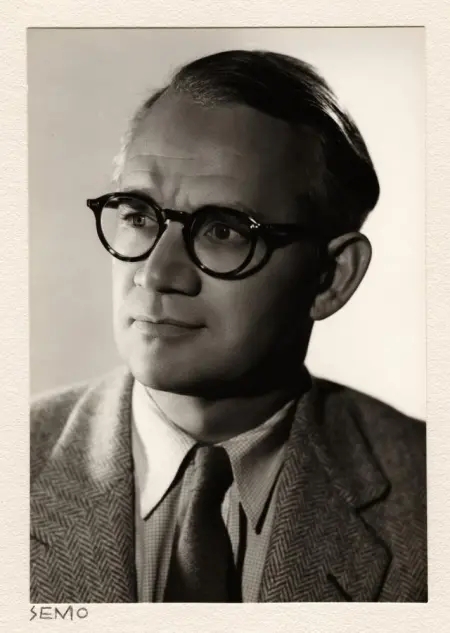

Commemorative marker for George Woodcock on McCleery Street, Vancouver (Coast Salish Territory). A bookcase-style monument to Woodcock also exists at the University of British Columbia where he taught

Also

Karl Marx’s Capital, by Carlo Cafiero (1879)

Karl Marx, from Le Révolté (1883)

Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume I, by Karl Marx (1867/1887)

Letter from Marx to Editor of the Otecestvenniye Zapisky (1877)

Letter from Vera Zasulich to Marx (1881)

Marx’s reply to Zasulich (1881)

Plea for Anarchy, by Albert Parsons (1886)

The Conquest of Bread, by Peter Kropotkin (1892)

Manufacturing Psychology, from Industrial Worker (1910)

The Sea-Serpent, by Tekahionwake (1911)

Fields, Factories and Workshops, by Peter Kropotkin (1912)

The Tyranny of the Clock, by George Woodcock (1944)

Time is Life, by Vernon Richards (1962)

The Reproduction of Daily Life, by Fredy Perlman (1969)

Capitalism, the Final Stage of Exploitation, by Lee Carter (1970)

Gabriel Dumont, by George Woodcock (1975)

A Critique of Syndicalist Methods, by Alfredo M. Bonanno (1975)

Marxism from a Native Perspective, by John Mohawk (1981)

Robotization: A Second Industrial Revolution, by John Mohawk (1983)

How We See It, by the Vancouver Five (1983)

Marxism and Native Americans, by Howard Adams (1984)

A Question of Class, by Alfredo M. Bonanno (1988)

From Riot to Insurrection, by Alfredo M. Bonanno & Jean Weir (1988)

George Woodcock, by BC BookLook (2016)

Head Hits Concrete, by M.Gouldhawke (2021)

The Social Interest and its influence on Capital, by M.Gouldhawke (2022)

The Labour-Power Theory of Capital, by M.Gouldhawke (2022)

What is the Proletariat?, by Zoe Baker (2024)

George Woodcock texts at the Anarchist Library