From ‘War Commentary: For Anarchism’, Mid-March & April 1942, London, UK

To civilised people today the position of the Jews is intolerable. In increasing numbers of countries the centuries’ plague of the ghetto and the pogrom is reviving. Against the mediaeval curse of anti-semitism, on the one hand, and the inevitable Jewish reaction to its own nationalism on the other, there must be some method of struggle.

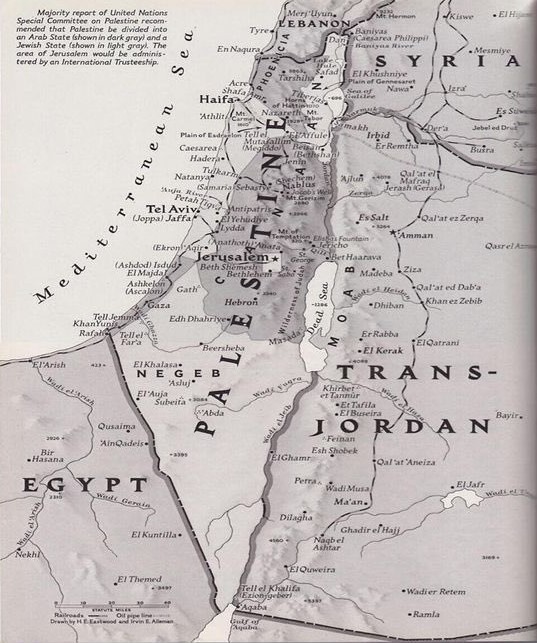

What is the method advocated by liberals and the left today? In the main it is agreed: the re-establishment of religious and racial tolerance in all countries, on the one hand; and the establishment of the Zionist aim — a Jewish National Home — in Palestine, on the other.

It is perhaps necessary to give first the background of Zionism, and the reasons why Zionism came into conflict with the Arabs in Palestine.

The first modern exponent of Zionism was Theodore Herzl. Moved by growing anti-semitic feeling in France and in his native Austria, and later by the feeling of sympathy with the persecuted Russian Jews felt by all sections, Herzl evolved his plan of a Jewish State. His idea was that the Jews could form a small nation somewhere in the world, and so end the national distinctions pervading amongst the Jews themselves.

It is sometimes said by Zionists today that Palestine was the end-all and be-all of Jewish hope and aspirations for centuries. This is not so. True, the Jewish religion has centred around the idea of “the Promised Land” which the Jews would re-enter but it was thought that only Messianic times would see the “Chosen people” arrive in Jerusalem. In short, the rabbinical idea of the “New Jerusalem ” was pretty much the same as the Christian. (The prayer concluding “Next year — in Jerusalem!”, for instance, has always been and still is used by Jews in Jerusalem, too). Only the portents announced in the Talmud could herald the return of the Jews to the “Promised Land,” and in fact the Jewish religion thought of Palestine as a spiritual, not a material, concept.

Prior to Herzl, hardly anyone ever dreamt of an actual return of the Jews to Palestine, and when Herzl’s plan was published, its fiercest opponents were the rabbis, it being contrary to all their teaching. They cast doubts on Herzl’s orthodoxy, helped by the fact that, like so many Austrian Jews, his father was a convert to Christianity and Herzl had been brought up as a Christian, returning to Judaism later in life. (It was asked contemptuously if Herzl considered himself King David!)

In addition to incurring the opposition of religious Judaism, Zionism was frowned on or ignored by the rich and powerful Jews, who naturally had no wish to see the status quo upset.

Herzl’s scheme might have appealed to the homeless, hungry and persecuted Jews of Russia. But a vague promised land had nothing on a definite Promised Land — America! Like the rest of Europe’s downtrodden they looked to the symbol of liberty that to Europe’s millions was represented by the United States. The acute labour shortage following the Civil War gave rise to a demand for labour — for immigrants — and the immigrants came in their thousands; Jews from the pogrom countries with the thousands of Italians, Irish, Latvians, Armenians, Poles, Czechs and the rest.

It rather seemed at first as if Herzl was to enjoy only the support of a handful of Jewish intellectuals and a number of influential anti-Semites (many of whom strongly advocated the acceding by the French Government of a plot of land in Africa for the settlement of the Jews — willy-nilly). At first the Zionists listened to the schemes of settlement in Africa, but under the influence of Herzl turned down all such promises. The choice was finally made — Palestine only. In this Herzl made a tactical move. He gave his movement a solid basis, by gaining religious Jewish support. While for long the orthodox opposition on the grounds that re-settlement in Palestine prior to the Messiah’s belated arrival was contrary to teachings, the rabbis were shrewd enough to realise that their shibboleths were crumbling, not against persecution but against tolerance. America, the “melting pot” of all nations, was assimilating its Jewish citizens too.

The same process was at work in South Africa, in Britain, in France, in Germany. Jews were losing their identity as Jews. Most of them were unable to believe in the God of their fathers (any more than their Gentile neighbours) they were forgetting the old codes and taboos. A “religious revival” was the Gentile reaction to 19th century agnosticism. This in turn passed to Fascism. With the Jews it was similar. The rabbis looked to a mystical nationalism, such as Herzl was advocating.

It cannot be said that the majority of Jews who pioneered Zionism in Palestine were orthodox Jews. Other than the Polish and Russian Jews, there were few orthodox Jews left. Palestine since has not been a home for orthodoxy. A modern Palestine Jew would not at all bother about a pork dinner in the shadow of the Wailing Wall. But orthodoxy has gathered more strength; and while it has not produced its goal — a Jewish religion and race separated from all others — it has helped to produce a separatist feeling amongst nationalist Jews that may (with or without the religious stimulus ) have far-reaching effects. In all this the whole outlook of Zionism was and is essentially reactionary and of a fascist nature. Prior to this aping Hitler’s anti-semitism, the Revisionists (right wing Zionist extremists ) did indeed look on Mussolini as an inspired statesman.

On the other hand, it is unquestionable that side by side with the pipe-dreams of a Messianic Jewish community in the Near East, and the nationalist aspirations of others, there existed a number of Jews who, with no sympathy with their abandoned religion, hoped Zionism might be a symbol of regeneration. It may not be altogether possible for Gentile readers to appreciate how bitterly they detested the racketeering elements who figured so prominently in the early days of South Africa. The entirely unscrupulous Rand financiers were too often Jews. A product of the inferiority complex engendered by separatism, and of the city, the gambling mob that disgraced itself was unquestionably regarded by large numbers of decent Jews as “the type of Jew who causes anti-semitism.” To get away from this city bred type they did hope for a national regeneration on the land. “To get back to the land” — ” regeneration on the soil” — it is the usual mystical nonsense that has a great appeal to people who themselves have not experienced the narrowness of life in an agricultural community, but so far as it was a reaction it was progressive.

The above gives a clear picture of the whole tenor of Jewry prior to the 1914 war.(Note 1)

The Balfour Declaration gave the Jews the right to a National Home in Palestine. While promising the Arabs and other subject peoples of the decaying Ottoman Empire full liberty in the post war world (added to the specious promises made by Lawrence and others) the idea of a Jewish State in Palestine was given life (which to the majority of people, including most Jews, was as fanciful a project as the establishment of an Eireann state in Ireland, with the old Gaelic language — or, since this too happened after the war — as if Sweden suddenly went Viking).

Why was the declaration made? It must have been realised that the Arabs, when free of Turkish rule, would not voluntarily submit to any other foreign domination. But, since it was decided that this strategically important country must be in the jurisdiction of the British Empire (to safeguard the route to India and the Orient), some plan had to be evolved of colonising the country in part. Evidently the British Government was influenced by the Zionist minority in agreeing to the idea of a Jewish Home in Palestine. The only alternative (in fact) was to settle emigrants generally, as in South Africa and Australia. But British emigrants were few (as colonial experience had shown): and it may well be that European emigrants were simply not trusted. Already in Canada and Australia the door was barred to the “teeming millions” of European immigration.(Note 2) In Palestine, too: none but the “reliable.”

The British Government was assured of Jewish reliability. While the Arabs could not be trusted from an Imperial standpoint (they would, like the Egyptians, raise awkward questions about autonomy) the war had proved that the Jewish community would respond to a patriotic demand. The majority of British Jews were viewed with suspicion at the commencement of the war of 1914. The fact that a majority of them were foreign born, and the anti-immigration agitation of the ’00s had been mostly anti-semitic rather than anti-foreign, was an incentive to the suspicion against them. Looting of shops bearing German names soon spread to looting of shops bearing Jewish — even Russian (then Allied ) names! The Jews had, however, not been provoked; had supported the war like the other communities.

Prominent in recruiting campaigns was the Chief Rabbi (Austrian born, and therefore an “enemy alien.” The German Chief Rabbi was also an “enemy alien” being Russian born!). Jews were volunteering and being drafted into the army. But even more there had to be considered the tradition of the upper class Jews, which naturally had more influence on the Government. The Disraeli tradition persisted in Lord Reading, there were the Rothschild and Sassoon dynasties, men such as Lord Burnham (founder of The Daily Telegraph) the circle of Edward VII, the Montefore family and others — the existence of whom assured the British Government of two things:

(1) that the leaders of British Jewry could be trusted to influence the remainder into supporting any Imperial designs in Palestine, and in regulating the European Jewish immigrants into that country along the same road. (Foremost among the “safe men” chosen for the regulation of Palestine was, of course, Lord Reading; the prominent bourgeois statesman whose administration in Palestine, as in India, combined “reconciliation” with implicit obedience to Imperialist dictates).

(2) that since the position of Jews in most countries was, following the changes made by the war, favourable, (and the Versailles Treaty was to last a thousand years!) only a minority of Jews from the ever-decreasing pogrom countries, plus a few Zionist idealists, plus some British Jews seeking administrative positions, would enter Palestine.

Hence immigration was intended to be controlled, regulated and shepherded into a steady colonising trickle that would act as a safeguard against anti-imperialist designs of the Arabs; would colonise the country; would build a European community able to commercialise the assets of the country and at the same time guard against foreign aggression towards the oil-fields of the Middle East, and the route to India.

At first Arab objection as such to the “Jewish National Home” did not arise, There was some Moslem rioting in Jerusalem in connection with the alleged “Holy Places” — but in Jerusalem, the “City of Peace” there has always been rioting over that! Trouble began first when the colonial enterprise became profitable, owing to the cupidity of both Jewish capitalists and Arab landowners.

Jewish capitalists from America were interested in the commercial proposition. They were building new industries and new towns. Tel-Aviv, for instance, rose from nothing to a new Chicago; farms appeared on what was once desert; Jerusalem, from being a sleepy Turkish provincial town where the different Christian priests quarrelled over their rights, became a hive of twentieth century industry. The Dead Sea became a live centre for tourists. In short, Palestine was being developed in the same way as South Africa had been, only in a much more rapid process. Unfortunately, contrary to the opinions of idealists who had hoped to pioneer an agricultural socialism, the same faults and methods of colonisation appeared in Palestine as in South Africa. (It is sometimes argued, of course, that capitalists coming into a country and colonising it develop the land “and make work for the natives,” an even more ironical statement than the old anti-socialist story that “the capitalist puts up the capital without which the worker could not work; hence the worker lives on the capitalist, not vice versa!”)

As for the Arab landowners, they were no less culpable than the Jewish capitalists. They sold their land at high prices to the investors, stretching the price to the highest conceivable limit because of the need for land, knowing full well what the sale of land would mean to their own peasants. Having forced the peasants off the land which they had sold at high prices to the Jewish investors, they told the peasants that the Jews had stolen the land, and carried a political agitation on to win back the land — in order to sell it again.

By virtue of their ties with Mohammedanism, the Arab landowners were able to influence the British Government. They were politically identical with the “Muslim League” minority in India, representing as it does the landowning and financial clique, and not the Arab peasants.

However, in saying that the Arab landowners took advantage of the Jewish influx to sell their land at high prices, and force down the standard of life of the peasant, this does not mean that it was not the case that the Arab peasant was forced off his land. The Jewish capitalist, and (playing a double game) the Arab landowner, were responsible. But because nationalist feeling is what it is, the Arab peasant thought of only the Jewish capitalist — and hence all Jews — as responsible. This explains the whole feeling of the Arab peasant. Led by a corrupt gang under the Grand Mufti, he could only see the whole thing as a national feud — Arab versus Jew.

In the same way, the average Jewish immigrant was not able to appreciate any reason for the disturbances that arose with intensity each year, culminating in the struggles of the late thirties. He came from Roumania, or Poland, or Hungary, where it was not unexpected for a sudden pogrom against the Jews. Escaping from his country, he arrived In Palestine, hoping to form a nation of his own. On arriving in Palestine, he found the Arabs incensed at the arrival of Jewish immigrants, hostile to the outlying settlements, unfriendly, and finally openly taking to arms. What could he think, except that the pogrom spirit had followed him across Europe to the “Promised Land”? What alternative could he see except the continuance of the national feud?

In short the Jewish immigrant was brought over on a short term policy of the Jewish capitalist: and the capitalist was aided by the Arab landowners to force out the Arab peasant.

The policy pursued in Palestine, therefore, could only lead to disaster. The Arab peasants were forced off the land, and saw relief only in the national feud. There was a section that saw relief in assistance from the Axis powers, “since they too were against the Jews”(Quite obviously this was nonsense; European anti-semitism would speed up Jewish immigration into Palestine rather than the reverse. The Axis was interested in fostering its agents amongst this section because of the very tactical nature of Palestine in the Mediterranean, rather than from any motives of ideology). There were also the wealthy Arabs who looked forward to a scheme of division, in which their own future would be assured, by the scarcity of land and hence Its high market value. (This scheme, roughly resembling the “Pakistan” of some of Mr. Jinnah’s followers in India, but in a much smaller country, would have allowed so many cantons on the Swiss model to Jews, and so many to Arabs). The whole civil war that blazed up in Palestine was in the, last analysis vain; because the nationalist leaders would not in any case have looked for sole independence, but merely an end of the system of colonisation being pursued.

On the Jewish side, the persecutions breaking out again in Europe had brought a large-scale immigration to Palestine. For a long time Hitler permitted the Zionist organisation to exist, and it enjoyed the unenviable position of being the only non-Nazi political organisation in Germany tolerated by the State. The leaders of Jewish communities, particularly in America, accentuated the efforts to get Jewish families out of Germany, especially into Palestine. The British Government which had never foreseen such a move, was reluctant to permit this, particularly since it did not wish to disturb the situation In Palestine any more. The whole effect of the Palestine experiment so far as the victims of Hitlerism were concerned was to raise a false chimera of hope before them, of allaying anti-Nazi feeling which would have broken out in Germany itself on this issue had not the Jewish homelessness been· explained away by “but the Jews have somewhere to go — it’s the British Government that prevents it,” and most of all it encouraged the Governments that wished to have an excuse not to admit immigrants themselves, but to express their desire for the refugees to enter somewhere– in particular, the American Government.

Can the Zionist Experiment be Pursued Further?

It does not seem as if abandonment of Zionism is anyone’s war aims. The British Government no doubt intends to continue as before, allowing a trickle of immigration, not to disturb its present basis. Hitler too wants a Ghetto State — a Jewish “Pale of Settlement,” but apparently in the worst areas of Poland. Palestine itself is no doubt regarded by the Nazis as a vital link which they would colonise themselves, In short, a Nazi victory in the war would mean the re-colonisation of Palestine, and the position in a few years’ time would be similar to today. An oppressed Arab population would be still struggling for independence.

A British victory no doubt means the status quo in Palestine. But we have the usual claims on the Government, and policy may be influenced in one or the other direction. Ever since the war began the Revisionists, and later most Zionists, have been clamouring for a “Jewish Army” in Palestine, with its own flag, its own divisions, its own commanders, on a level with other Allied nations. In vain has the Government explained that there is no Jewish State, that Jews are citizens of other States, consequently Jews can only be soldiers of the armies of the Allied Governments and not of their own non-existent Government. There Is no pressing demand by Jews in the ranks to have their own Army, why therefore create one? Yet the demand persists, especially from American Jews (Dr. Abba Silver is at the moment in England on this very mission). The answer is obvious. They want a Jewish Army based on Palestine as the thin edge of the wedge for a Jewish State based on Palestine.

Why should this demand be so popular amongst American Jews? They have no disabilities in America; there is no urgent need for an exodus of Jewish refugees from New York; the problems of European anti-semitism do not affect them. It must be admitted that American Jews thinking of the creation of a State in Palestine have no intention of taking its citizenship themselves. They want to see the State, but with citizens strictly limited to those from Europe. They cannot see that actually they themselves are preparing the ground for American anti-semitic laws.

For essentially the whole prospect of Zionism for the Jews is as unsatisfactory as it is for the Arabs. The exclusion of the latter from their homes is equally balanced by the exclusion of the former. The gainer In each case is the coloniser and the landlord; and the loser both the immigrant worker and the native peasant.

The kind of Zionism envisaged before the war meant essentially co-operation with Hitler and other anti-semitic rulers. The kind of Zionism envisaged for after the war means that it is considered that anti-semitism will still prevail in the countries from which the settlers are emigrating.

The solution of Jewish miseries in the world today does not therefore lie in Zionism (nationalism); it lies in the fight against anti-semitism, and hence the fight against nationalism.

In the last analysis, the solution to the whole problem of Jewish homelessness and persecution, lies in the solution to the problem, of the workers everywhere: i.e., the building of a world freed from nationalism and States.

But it may be asked, can this particular problem wait? No problem can wait. A desirable conclusion may have to wait, but the means of action must be taken now.

In Palestine

It is clearly difficult and nearly impossible for the anti-Zionist Jew in Palestine itself to take action. He not only incurs the hostility of the majority of other Jews, but cannot allay the suspicion of the majority of Arabs. But an anti-Zionist minority, and a class-conscious Arab minority too, can grow, and from the nucleus of a minority of revolutionary Jews and Arabs can grow a movement with the main principles:

(a) the abandonment of the Zionist State experiment on the one hand, and of an Arabic kingdom on the other;

(b) anti-imperialism, opposition to external capitalism and internal landlordism;

(c) disregard for the religious scruples causing barrier amongst the people;

(d) the struggle for an independent workers’ country, to take its place amongst other independent workers’ countries of the new world, on the same principles of revolutionary libertarian socialism (and with absolute disregard for race).

I do not say such a minority with such a programme is an immediate likelihood, but it is towards the creation of such a minority that the policy of revolutionary workers elsewhere must be. It would not matter whether such a movement were inaugurated solely by Jews or solely by Arabs; the point is that such a movement can arise to take in all of whatever nationality. It is by aiming at such a movement, and not by supporting any propositions which may come from interested parties during this war, that the revolutionary workers may know they are not being misled by false nationalist divisions once again.

On the question of Arab Independence: it may be that Arab revolutionaries would feel themselves bound to a movement of Arab independence, similar to Indian and Moroccan revolutionaries. We agree, it may sometimes be necessary to go part of the way with colonial bourgeois nationalists; but our aim in all cases is to expose the leaders of the colonial peoples, and point the way to their own emancipation. The support of any independence movement should not therefore prejudice the main object, that of a movement of all the toilers.

In the Rest of the World

This may well point to a course of action for the Jews of Palestine, but it will be argued that the Jews in the pogrom countries will be left without hope, except with the hope of far-off revolution. In the first place, this is an improvement, for even the hope of a revolution and a free system of society in the future is more practicable than the hope of a peaceful national state, when one views the position of all other small states, in far less strategic positions.

Moreover the course of revolution can be pursued, but as the “Struma” tragedy shows, the Governments of the world have no intention of letting immigration be pursued. It may be that Herschel Grynspan, before the war, had a clearer notion than many of the worthies who washed their hands of him, as to how the pogrom governments should be fought. It was better to have struck at Vom Rath than to have committed suicide, at least; and while perhaps it did not accomplish much — had not Grynspan been denounced so readily by those who wished to show they had nothing to do with it — the example might have been contagious.

We do not have to go into details to show that fascism can be fought from within. It goes equally to show that anti-semitism is a product of capitalist and nationalist society, and that it can be equally fought with the system by the revolutionary workers; that in fact, a government cannot impose it without the aid of the masses (as witness Holland, Denmark and Norway, countries where the virus of anti-semitism had never infected the masses, and where the Nazis have been unable to carry through the Nuremberg laws).

Countering nationalism with nationalism does not solve a national problem, The revolutionary class struggle does. Anti-semitism will finally be smashed by the revolutionary class struggle, if pursued logically. And the logical course of the class struggle is not to confuse anti-semitism with anti-Zionism. The former is reactionary, but the latter is one of the means of fighting the former.

A.M.

Notes

- The interested reader will find profitable study in many of the novels of Israel Zangwill (“The King of Schnorrers?” “Children of the Ghetto” etc.) whose pen has made a truly Dickensian survey.

- The U.S.A., when padlocking the doors to the European immigration that evolved it, gave the reason in its notorious declaration that all persons entering the U.S.A. (even on a visit) are compelled to make — one effectively ruling out anarchists, radicals, — even democrats!

Also

Palestine and Socialist Policy, by Reginald Reynolds (1938)

Reg. Reynolds Answers Emma Goldman on Palestine (1938)

Anarchist Tactic for Palestine, by Albert Meltzer (1939)

The “Advantages” of British Imperialism, by Reginald Reynolds (1939)

Tribunals and Political Objectors, by Vernon Richards and Albert Meltzer (1940)

Conspiracy on Palestine, by Reginald Reynolds (1941)

National Independence, by Albert Meltzer (1942)

Zionism, from War Commentary (1944)

Fine Day For The Race, by Albert Meltzer (1947)

Malaya, by Albert Meltzer (1948)

Palestine, by Albert Meltzer (1948)

Middle East Notes: Civil War, from Freedom (1948)

Should We Defend Democratic Rights?, by Albert Meltzer (1951)

Wounded Knee: The Longest War 1890-1973, from Black Flag (1974)

Review of ‘Open Road’, by Cienfuegos Press Anarchist Review (1977)

Alternatives to Suicide, by Albert Meltzer (1981)

Into the Green, from Black Flag (1989)

Solidarity from Anti-Authoritarians, by Leonard Peltier (1991)

The Start of Black Flag, by Albert Meltzer (1996)

Anarchism: Arguments For and Against, by Albert Meltzer (1996)

Farewell Albert, by Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin (1996)

Albert Meltzer, anarchist, by Stuart Christie (1996)

Albert Meltzer texts at the Anarchist Library

Texts by or about Albert Meltzer at the Kate Sharpley Library

Texts by or about Albert Meltzer at Libcom

One reply on “Palestine and the Jews – Albert Meltzer (1942)”

[…] Palestine and the Jews – Albert Meltzer (1942) […]