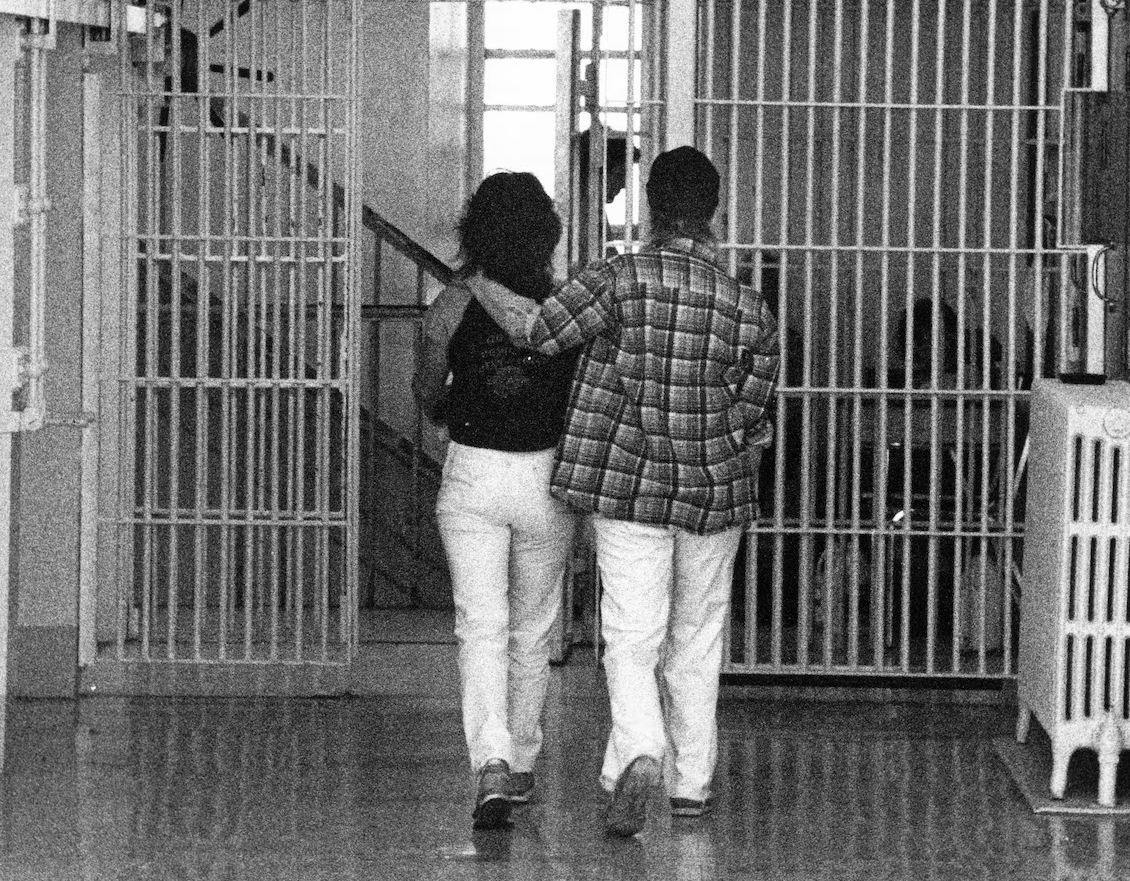

Photo credit: Thomas Szlukovenyi

Text of an undated pamphlet distributed by the Prisoners’ Justice Day Committee. For more information on women in prison check out their website at www.prisonjustice.ca

Three months after Kingston Penitentiary (KP) was first opened for men in 1835, the first three federal women prisoners were led inside its cold grey walls. They were originally held in the infirmary because there was no place else to put them. By 1913, their numbers had increased dramatically and so they were placed in a new building known as the northwest block, still inside KP. By 1934, the first forty federal women prisoners in Canada were transferred into the Prison for Women (P4W).

Almost one hundred and seventy years later, it would be wonderful to exclaim, “how times have changed!” But instead, the somber realization that history is doomed to repeat itself comes to mind. In April 1994, six women were involuntarily transferred from P4W to a segregated range inside the old limestone walls of KP. Echoes from the past. Nine years, and many official condemnations later, there are now four maximum security women’s units inside men’s maximum security prisons across Canada. The maximum security women inside Saskatchewan penitentiary for men are kept in the old men’s psychiatric unit because there is nowhere else to put them. More echoes from the past.

In his 1998-1999 Annual Report, an understatement by someone as officious as the Correctional Investigator for the Correctional Services of Canada (CSC), said, “The Services interim policy decision to involuntarily house maximum security women and women with serious mental health problems in male penitentiaries has gone on too long.” I wondered if he was referring to 1835 when he said, “too long.” He goes on to say in no uncertain terms that “The findings of this office suggest that such a placement is inappropriate for women with a history of physical and sexual abuse and regardless of the accommodations made, it is in fact segregation… I recommend that immediate action be taken to address this totally unacceptable situation.” I regret to inform the reader that as of today, nothing has been done with the exception of plans to build a maximum security section on the women’s prison in Kitchener, a plan whose implementation could take decades if we are to judge it on past performances.

The history of federal women prisoners is riddled with scathing reports and condemnations of their prison, conditions and yet, to my knowledge, the situation for women prisoners in Canada has not changed since P4W was first described as “unfit for bears” by the Archambault Royal Commission, 4 years after the first women were moved from KP in 1934. By 1990, the Task Force on Federally Sentenced women was the 50th federal report to chronicle the inadequacies of prison conditions and programs for women. I became personally aware of the repetitive nature of history in January this year, when I attended a Canadian Human Rights Commission conference to once again document cases of discriminatory treatment of federally sentenced women (FSW) in preparation for a government brief. During this conference, I became aware that the same Commission had condemned the CSC for discriminatory treatment of FSW in a government report in 1981. I ask myself, why does the government continue to waste money on report after report that condemns prison conditions, recommends improvements and then refuses to act upon these recommendations?

I was a federally sentenced prisoner from 1983 until 1990 and will be on parole for the rest of my life. During the latest Human Rights Commission conference, I was asked to testify about my experiences in the prison system. Since I had been out of prison for twelve years, I decided to contact a few women I knew still inside the federal prisons to compare how much prison conditions had changed since I had been released on full parole. I must admit, I wasn’t shocked by their testimony, but my cynicism regarding prison reform became even more grounded in reality than ever before.

In 1983, most women serving life sentences were transferred to P4W as maximum security prisoners to do their time along with medium and minimum security prisoners. As maximum security prisoners, we lived in a population of roughly 100 women who moved about freely from work to their ranges or wings and the yard. There were jobs available for all security levels although they were menial and certainly did not prepare the women for employment on the street, but at that time, it was possible to take university courses or upgrade one’s education in the prison school. Other than AA, I can’t recall any treatment programs for drug and alcohol addiction, and there was one psychologist who specialized in sexual abuse counseling. It might not seem like much, but in the evenings and weekends, we could paint and decorate our cells to reflect our personal identities and could associate in common rooms, play sports in a full size gym, work out in a weightroom, or jog in a fairly large open prison yard. When a maximum security prisoner became a medium security prisoner, not much changed, but there was the possibility of moving to the wing; an area somewhat like a dorm with unlocked cell doors, and windows in each cell.

By the time a prisoner cascaded to minimum, it was possible to get the odd institutional group pass to go swimming at Artillery Park, or even be transferred to the Isabel McNeil House, a minimum security house across the road from P4W. At the minimum, women could work in the community, lived in a house without security fencing, could cook their own meals and generally take on the responsibilities of normal life. Finally a prisoner could apply for day parole at the Elizabeth Fry Detweiler House in Kingston which also served as a place where women could stay while on passes. Although this may sound idyllic to proponents of capital punishment and the concept of prison as retribution, in reality, prison conditions and programs in the 80’s were so inadequate that the overwhelming effect was one of punishment. Unfortunately there is not space in this article to argue why prison programs and facilities are positive and necessary for the reintegration of prisoners but suffice it to say that countless studies have concluded “they are a good thing” for society.

P4W’s final death knell came in 1994 when a murky black and white video that resembled a low-budget pornography film was aired across the country on the evening news showing the male riot squad in full facial masks stripping female prisoners of their clothes with scissors against their will in the segregation cells of P4W. These scenes of degradation had taken place after the prisoners had already been locked in the segregation cells following a confrontation with female guards. Even though most federal women prisoners can recount equally horrific experiences, the public was shocked to learn that these grainy porno scenes were real TV taped directly inside Canada’s modern prison system. The government responded predictably by setting up another Commission headed by Justice Louise Arbour to investigate and then make recommendations into what was officially described in terms that could only serve to downplay the crisis, “An Inquiry into Certain Events at P4W”.

Two weeks after having their clothes cut off by male prison guards, the six women involved were involuntarily transferred to a segregated range in KP, a prison noted for taking the unwanted sex offenders from the other men’s maximum penitentiaries. The women were eventually transferred back to P4W after arguing successfully among other things to the Ontario Court that they had histories of being sexually abused by men and did not feel safe in KP. Many months of testimony and thousands of dollars later, to no one’s surprise, the Commission recommended that P4W be closed and, once again in its characteristically understated way, concluded that “there is, if nothing more, an appearance of oppression in confining women in an institution which will inevitably contain a large number of sexual offenders. This is particularly true of the Regional Treatment Centre (KP). More troublesome, in my opinion, is the fact that the placement of a small group of women in a male prison effectively precludes their interaction with the general population of that institution. If transfer inevitably means segregation, the decision to transfer should take into account the limitations on the permissible use of administrative segregation.”

Despite the Ontario Court General Division, the Arbour Commission and the CSC’s own Correctional Investigator, here we are in June 2002, not 1835, with small groups of women prisoners being confined in virtual segregation within men’s maximum security penitentiaries; namely Springhill Institution in Nova Scotia, the Regional Reception Centre in Quebec, the Saskatchewan Pen. in Prince Albert and the Regional Psychiatric Centre in Saskatoon. These women’s maximum units share strikingly common denominators; each unit has a population ranging from 1 to 12 women who are kept in virtual isolation from the general men’s population; they have either limited or no access to work, recreation or treatment programs. Life in these women’s units bears more of a resemblance to that of special handling units designed for men who have killed guards or other prisoners, than it does to that in a general prison population. Theoretically at least, these women are being held in these units because they are maximum security prisoners, not for special punishment.

The situation in Saskatchewan Penitentiary is typical of life for a woman as a maximum security prisoner. You would be placed in an open-barred cell similar to the kind you see in stereotypical Hollywood films on a small range with 3 or 4 other women. No matter how many layers of paint they apply, nothing can erase the haunting thoughts that plague you, knowing that this used to be the men’s psychiatric unit, and nothing can stop you from contemplating the fact that you share more in common with those first three female prisoners in 1835 than with any women in the 21st century. Every day of your life you wake up to the clanging of the metal doors unlocking, opening up your cell to the same 2 or 3 other women you will share a tiny common space with for many years. There are 5 other ranges just like yours in this unit but you won’t get to associate with the 2 or 3 women there, or with the 500 men who live in the rest of the penitentiary around you. And you pray at night when you hear loud mysterious noises that those 500 men are not in the midst of a riot progressing rapidly towards your unit. Let’s face it, can anyone think of a men’s maximum prison that has not had a major riot? I can’t. And I can’t think of a men’s maximum prison that doesn’t have some sexual predators either openly or covertly prowling its ranges. Considering that you are one of the 80% of all federal women prisoners who have been sexually abused, you are not always comfortable being escorted to and from the few activities available through the men’s areas. But at the same time you feel like you are going to either explode or implode if you have to spend another day in that small space with the same 2 or 3 people. Your meals are even delivered onto the tiny range from the men’s area and you share a shower with the same 2 or 3 women. Inevitably tension builds. And you find small consolation in the words of the Correctional Investigator condemning your situation as “unacceptable and discriminatory” even for prisoners.

Every time there is a crisis within the prison system, the government diverts the anger of society and its need for a resolution into some government commission, inquiry or report. They began in P4W just four years after the prison opened with the Archambault Royal Commission. Since 1968 no less than 13 government studies and private sector reports have reaffirmed that P4W should be closed. In 1978, when Solicitor General Jean-Jacques Blais announced that the prison would be closed within a year, instead, he turned around and built a new 18 foot high concrete wall. Then again in 1990 a federal Task Force recommended the closure of P4W, an occasion which the Solicitor General Pierre Cadieux used to pronounce the imminent construction of 5 new regional prisons for women at a cost of $50 million. Both the wall and the closure of P4W are good examples of how recommendations by commissions, inquiries and reports are invariably transformed into more prisons, more security and more prisoners.

At the latest Human Rights Commission conference, I was surprised to learn that the Canadian Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights applied to prisoners. I think my surprise was based on the incredible gulf that exists between the existence of these rights in theory and their actual application in reality. If I hadn’t experienced firsthand just how vacant the promise of human rights is in prison, I would be the first person to suggest that perhaps all the good intentioned recommendations of the various government commissions could be implemented through legal pressure to have prisoner’s rights upheld. But unfortunately I know all too well, how much of a mirage those prisoner’s rights really are. Ask the women in Saskatchewan Penitentiary about ‘freedom of assembly’ which even the CSC states, “inmates are entitled to reasonable opportunities to assemble peacefully and associate with other inmates within the penitentiary, subject to reasonable limits as are prescribed for protecting the security of the penitentiary or the safety of persons.” Ask any prisoner about freedom of speech. Charges stemming from arguing with guards are systemic. Ask prisoners anywhere about freedom of religion. Unless a prisoner is catholic or protestant, there are few religious or spiritual “leaders” who have access to prisoners to guide people in their traditional ceremonies. Ask prisoners about freedom of the press. When I was released I was sent a box full of magazines, newspaper articles and books that I had never even been notified of being denied. And of course federal prisoners can’t vote. The list of freedoms and rights that is not applicable to prisoners is too vast to expand upon in this article.

So why should we care about what happened to those women in P4W anyway? Prison is the looking glass of society. It reflects what the values and characteristics of our society are. What do we see through the looking glass? We see women who are the most victimized people in our society. They are the poorest, least educated, and most racially discriminated. They have been physically and sexually abused at the hands of their own fathers and mothers, and then deserted by the fathers of their children. Is this just political rhetoric, you say? The numbers paint the picture, I answer. 50% of FSW have a grade 9 or lower education; 40% are illiterate; the majority were unemployed at the time of their crime; even though native people make up 2% of the population, they are 25% of the FSW; 2/3rds are single mothers and 80% have histories of sexual or physical abuse. And even when women do commit violent crimes, 62% are classified as common assault and the majority of those convicted of murder have killed a spouse or partner who they reported as having physically or sexually abused them.

No matter how I look at it, the women in prison are the victims of the inequities, the injustices and discrimination within our society. Without prisons as a social control mechanism, the poor would take back what is rightfully theirs; the rebellious would no longer obey laws they know are unjust; and revolutionaries would win the just war. Execution is the only social control mechanism more effective than prison.

If only I could say the solution was reform and the struggle for prisoner’s rights, but unfortunately the contradictions within the capitalist economic system make these solutions illusory. To pursue prisoner’s rights is somewhat akin to a heat weary traveler in the desert trudging endlessly towards a shimmering mirage over sand dune after sand dune. No matter how close the traveler gets to the oasis mirage, just as it seems within reach, it disappears over the next rise. Is this not what has happened with the closure of P4W? The prisoners were promised better prison conditions. Now we see women in tiny units inside men’s prisons, and the mediums and minimums are living in small regional prisons with few treatment or educational programs. The government claims there are too few women prisoners spread out across the country to make programs cost effective. Yet millions of dollars have been spent on converting ranges in men’s prisons into segregated women’s units.

Despite the seemingly hopeless task of improving prison conditions, we can’t just turn our backs and walk away from the women and men in prison. It’s important to try to help them even if the gains are few and far between. Certainly even what may seem like a small improvement is a big improvement for someone in prison.

So what is the key to solving this contradiction between working for prisoner’s rights, and living within a capitalist economy where prisons are an essential social control mechanism? I believe that Claire Culhane, who died in 1996 after devoting the better part of her life to abolishing prisons while fighting for prisoner’s rights, had found the key to unlock this puzzle. It is found in the simple words she inscribed on the letterhead of her Prisoner’s Rights Group; “We can’t change prisons without changing society. We know that this is a long and dangerous struggle. But the more who are involved in it, the less dangerous, and the more possible it will be.”

Also

Taking Our Lead From Women Prisoners, by Kendra Cowley (2024)

Prisoner Resistance Across the Prairies: 2022-2005, edited by M.Gouldhawke

“Chip away at it”: A year of COVID-era hunger strikes in Canadian prisons, by MJ Adams (2021)

Women Doing Time, by Marius Mason (2019)

Taking the Rap: Women Doing Time for Society’s Crimes, by Ann Hansen (2018)

Passion for Freedom, interview with Jean Weir (2010)

Native Spirituality in Prisons, by M.Gouldhawke (2005)

Direct Action: Memoirs Of An Urban Guerilla, by Ann Hansen (2002)

At home in the house of the Lord, from Open Road (1984)

Against the Corporate State, by Gary Butler (1983)

How We See It, by the Vancouver Five (1983)

Protect the Earth, by the Free the Five Defense Group (1983)