Art by way of Paris-Luttes

From ‘Freedom: Anarchist Weekly’, May 25, 1974, London, UK

A whole era in the history of anarchism came to an end with the death of Lilian Wolfe, for she was the last active link with the movement which was shattered by the experience of the First World War and the Russian Revolution.

Lilian Gertrude Woolf (as her surname was originally spelt) was born at her father’s shop in Edgware Road, London, on 22nd December 1875. Her father was Albert Lewis Woolf, a jeweller from Liverpool of Jewish origin and conservative views; from him she got her solidity of character. Her mother was Lucy Helen Jones, an actress from Birmingham whom she later described as “a very frustrated woman”; from her she got her independence of thought and action. Lilian and her three brothers and two sisters were brought up in a conventional, comfortable middle-class way until she was thirteen years old, when their mother deserted the family to join an operatic company touring the world.

Lilian had virtually no formal education, being taught by governesses and briefly attending the Regent Street Polytechnic before she began to make her own living as telegraphist. For twenty years she worked at the Central Telegraph Office in London, where she “hated every minute of it”, but where she nevertheless made many friends who “had a good influence over my choice of literature and culture generally”. Eventually she became a socialist and a suffragist, joining the Civil Service Socialist Society and also the Women’s Freedom League (this was a small body which broke away from the large Women’s Social and Political Union in 1907 because of the autocracy of the Pankhursts, and which was led by the equally militant but more democratic Mrs Despard). Her experience in these two organizations gradually brought about her disillusionment with both orthodox socialism and orthodox suffragism, and convinced her of the futility of conventional political action. At the same time she became a vegetarian and joined the health food movement.

By 1914 Lilian had evolved into anarcho-syndicalism, and with some friends began looking for a way to spread libertarian ideas more widely among working people. This was how she began a libertarian career which continued for the next sixty years, falling roughly into three phases.

FIRST PHASE

1914 – 1916

The first and most intense phase of this astonishing career lasted for less than three years. Back in 1907 the Freedom Press, which had published the monthly anarchist paper FREEDOM since 1886, had, for a time, also published a weekly syndicalist paper called the VOICE OF LABOUR. The new group was introduced by Mabel Hope, an anarchist feminist who was a frequent contributor to FREEDOM, to Thomas Keell, the editor, printer and publisher of FREEDOM and manager of the Freedom Press, and they all decided it was worth repeating the experiment. The new VOICE OF LABOUR began publication on May Day, 1914. (At first it was a weekly, but it became a monthly when the First World War began in August 1914.) The editor was Fred Dunn, but most of the work was done by Lilian.

This was a difficult time for the anarchist movement which, like the wider socialist movement, was split over the war issue. For a few months FREEDOM tried to remain an open forum, accepting articles and letters from both sides; it was not until the end of 1914 that Keell finally broke with the pro-war minority, led by Kropotkin, and decided to make FREEDOM a definitely anti-war paper. The VOICE OF LABOUR, on the other hand, was uncompromisingly anti-war from the start, and Lilian was one of the most active of the anti-war majority in the anarchist movement.

She was one of the members of the new Freedom Group, which was formed at the beginning of 1915 to run both papers. She was one of the founders of Marsh House, the anarchist commune which opened in Mecklenburgh Street, London, in February 1915. She was one of the signatories of the International Anarchist Manifesto on the War, which was issued also in February 1915. And she was one of the delegates at the national conference held at Stockport in April 1915, which unanimously opposed the war and unanimously supported Keell’s actions in holding FREEDOM to an anti-war position, despite a bitter attack from some of the older comrades.

The struggle against the war became more critical as conscription approached. Back in November 1914 the VOICE OF LABOUR had already attacked both the campaign for conscription and the purely verbal campaign against it: “’Wordy denunciation and protest is not enough; physical resistance must be our business.” Lilian was one of the founders of the Anti-Conscription League, which was formed in May 1915 when the new Coalition Government began to move towards conscription, and which called on workers to refuse call-up. The real crisis began with the passing of the Military Service Act in January 1916. FREEDOM and the VOICE OF LABOUR both printed appeals for more than conscientious objection, and also began printing reports of the experiences of anarchists who got into trouble with the authorities. It was not long before these included those mainly responsible for producing the two papers.

In April 1916 the VOICE OF LABOUR printed a front-page article called “Defying the Act”, written by “one of those outlawed on the Scottish hills”, claiming that “a number of comrades from all parts of Great Britain have banded themselves together in the Highlands, the better to resist the working of the Military Service Act”. Lilian later recalled being in bed with influenza at Marsh House when the group met to discuss the article, “and me, of all people, dissuading them from cutting out part of it, which a few thought a bit too much”. In May the VOICE OF LABOUR reported the arrest of most of the outlaws, and there is no evidence that there were more than a few people involved for more than a few weeks. But the idea was dangerous, and in the meantime 10,000 copies of a leaflet reprinting the article article had been produced by Keell and distributed by Lilian. Some were posted to Malatesta, who was living in exile in London and was not surprisingly; under police surveillance, and when they were intercepted the authorities decided to take the opportunity to attack the two leading troublemakers. The Freedom office in Ossulton Street was raided on 5 May, and Keell and Lilian were arrested.

They were tried at Clerkenwell Magistrates Court on 24 June under the Defence of the Realm Act for conduct “prejudicial to recruiting and discipline”. Keell pleaded not guilty and made a vigorous defence; Lilian pleaded guilty, remarking that “there seemed little to say, as her whole crime appeared to be that of telling the truth”. Keell was fined £ 100 with, the alternative of 3 months in prison, Lilian £ 25 or 2 months. Both refused to pay and were imprisoned. By that time they had become companions and Lilian was pregnant, so she was kept in the hospital at Holloway Prison. She was treated well enough (except by the chaplain who pretended to believe that she was German and threatened her with deportation), but she became worried about the possible effects on the child, and paid her fine two weeks before she was due for release.

The Freedom office was raided three more times before the end of the war, but somehow FREEDOM managed to continue publication. The VOICE OF LABOUR, however, was forced to cease publication after August 1916, and Marsh House had to close. Most of the militant men were in prison or hiding, and Lilian felt she could fake no further direct, part in the struggle; she moved into a more peaceful stage of her career.

SECOND PHASE

1917 – 1943

Lilian had resigned from the Post Office before going into prison,, and on her release she was cared for for a time by rich comrades. When her child was old enough to be looked after, she began to make her living again. For more than 25 years she managed health food shops, first in London and then in Gloucestershire. From the proceeds she and Tom were able to live and to bring up their son and also to keep FREEDOM going for several years during the decline of the anarchist movement after the First World War and the Russian Revolution.

During the 1920s she spent most of her time living at the long-established Whiteway Colony in Gloucestershire and keeping a shop in the neighbouring town of Stroud. Tom still spent some time in London, struggling to keep FREEDOM alive. But in 1927 the paper was finally forced to cease publication and in 1928 he moved permanently to Whiteway, continuing to produce occasional issues of a Freedom Bulletin until 1932 and also to distribute books and pamphlets. Whiteway was important to them both, as a model of the society of the future as well as a happy refuge from the unhappy society of the present. Each individual or family had its own home, but met in common rooms, and all members had a voice in running the whole community on a free and equal basis. Both Lilian and Tom were at various times Colony Secretary. Even here, though, the political struggle continued. Sharp differences between libertarian and Marxist elements emerged at the meetings. In the old days decisions had been made on the Quaker pattern, but voting became accepted in due course, and the libertarian way of life tended to fall into the background.

A separate Freedom was produced monthly from 1930 by a rival group, which included some of those who had opposed Tom during the war; but it too ceased publication in 1936. At that point Vernon Richards began SPAIN AND THE WORLD as a new monthly anarchist paper taking up the tradition of the old FREEDOM, and Lilian and Tom gave it their full support. It was published by Tom until his death in June 1938, and after that Lilian continued to help, coming to London to work in the office at weekends. The Spanish Civil War ended and the Second World War began, and the paper changed its name to Revolt! and then to War Commentary. Once more it was a difficult time for the anarchist movement. In 1943, at the age of 68, Lilian gave up her shop in Stroud; but, far from retiring, she now began the third and possibly most important phase of her libertarian career.

THIRD PHASE

1943 – 1974

For more than 25 years Lilian Wolfe was the basis of the administration of the Freedom Press at its various premises — Belsize Road, Red Lion Street, Maxwell Road , and Whitechapel High Street. She was that person on which every organisation depends — the completely reliable worker who runs the office, opening and closing the shop, answering the telephone and the post, doing the accounts and keeping people in touch, and generally keeping things going. She was an indefatigable correspondent, keeping in personal contact with the thousands of people who read the paper – which changed its name back to FREEDOM in 1945 – and with many other old anarchists and new ones all over the world. She was normally the first contact new recruits made with the formal anarchist movement when they wrote to the Freedom Press or visited the Freedom Bookshop; hers was the bold handwriting in blue ink or the unobtrusive presence in the office which became such a familiar feature of British anarchism after the war.

Lilian’s name hardly ever appeared in print — “I am no writer,” she said — but she played a more important part than many comrades whose names were always in the paper. Although she remained above all the administrator of the movement, she was no cipher. She signed one of the many protests against Herbert Read’s acceptance of a knighthood in 1953, and when the nuclear disarmament movement emerged she became an enthusiastic supporter. She was to be seen on every Aldermaston march from 1958 onwards, and she similarly attended several of the Committee of 100 sit-downs between 1961 and 1964; she was once more arrested and fined, and her only concession to age was that this time she paid up.

Lilian was perhaps best known for her incredibly Spartan way of life — as described by Vernon Richards in his memoir (11 May). She not only managed to live on her meagre pension and frugal savings, but she actually managed to put some money aside. This she carefully distributed to libertarian papers, to political prisoners, and to other deserving causes. The amounts were not large, but they were regular and, considering their source, remarkable.

In 1962 Lilian had to move to Cheltenham for family reasons, and it seemed that she might retire at last. But she was soon back in the office, working in London during the week and returning to Cheltenham for the weekend, a pattern she maintained for another twelve years. On the occasion of her ninetieth birthday FREEDOM printed a tribute to her work by Vernon Richards, and hundreds of members of the anarchist movement subscribed to give her a holiday in the United States, where she travelled in 1966 and met many old friends.

In 1969 personal differences at the Freedom Press led to Lilian’s departure from the office where she had served so long, but she expressed no bitterness and still did not give up her work for the libertarian movement. During the last five years of her life she continued to commute weekly between Cheltenham and London, working now at the offices of the War Resisters International and the National Council for Civil Liberties. Although she became increasingly deaf and frail, she kept her eyesight and her stamina, and week by week went on doing such essential but (to most people) tedious jobs as collecting press cuttings and stuffing envelopes. Typically she still asked for no reward or recognition, being quite surprised when the women’s liberation paper Shrew printed a long interview with her in August 1972.

Lilian never ceased her wide correspondence, and exerted a personal influence to the end. Near the very end she took pleasure in distributing the collection of books and other material accumulated by Tom Keell to various libraries and to a few individual comrades. Characteristically she delivered her donations in person, and thought nothing of visiting the Centre International de Recherches sur I’Anarchisme in Lausanne or the International Institute for Social History in Amsterdam. In September 1973 she was the oldest person present at the London meeting commemorating the centenary of the birth of Rudolf Rocker, and was suitably saluted by the large audience.

Predictably Lilian continued to work until only a month before the end, and did not finally take to her bed until the day before her death, when a series of strokes destroyed a body worn out by nearly a century of hard labour. On 28 April she died, as she wished, at her son’s home in Cheltenham. A notice appeared in the Guardian on 30 April, reporting her deaths “working usefully to the end… much missed by her family, comrades and friends”. Her funeral at Cheltenham Crematorium on 3 May was attended by a few of these; tributes were given by a member of the Whiteway Colony, Vernon Richards, Tony Smythe, and Lilian’s grandson, Richard Wolfe.

As Vernon Richards said in his memoir, “her long life was all of a piece”. As he said in his tribute in 1965, “Popular history is unfair in that it analyses and notes what the writers write and say, but overlooks what the inarticulate (that is, the non-writers) actually do and contribute to a movement.” If popular, or unpopular, history ever wants to describe the anarchist movement of the twentieth century, it will have to take account of Lilian Wolfe. Few comrades have lived so long, and few will live longer in our memory. Sleep well, Lilian — you have earned it.

N.W.

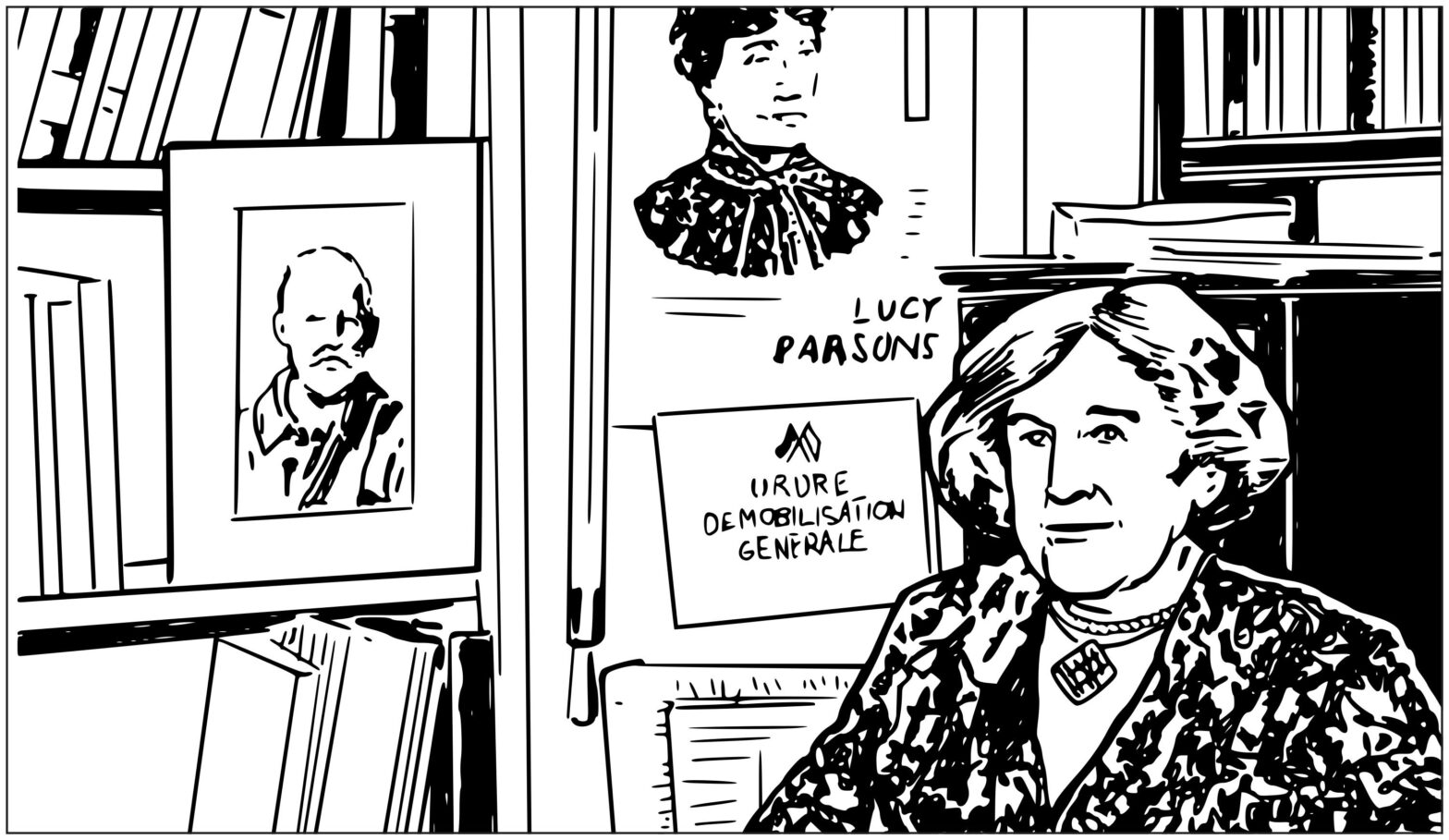

Marie Louise Berneri and Lilian Wolfe with War Commentary distro

Also

Walter, Nicolas, 1934-2000, from anok+peace

Still worth fighting: Nicolas Walter remembered, by Natasha Walter (2024)

Lilian Wolfe (1875-1974), de Paris Luttes (2022)

Anarchism and the First World War, by Matthew S. Adams (2019)

She [Lilian Wolfe] Lived Her Politics, by Sheila Rowbotham (1975)

Witness for the Prosecution, by Colin Ward (1974)

Lilian Wolfe – Lifetime Resistance, by Sandy Martin (1972)

Lilian Wolfe: On Her 90th Birthday, by Vernon Richards (1965)

The Avalanche, by Clara Cole (1947)

Rudolf Rocker and the Anarchist Stance on the War, by André Prudhommeaux (1946)

Ten Years a Soldier, from War Commentary (1944)

The Issues in the Present War, by Marcus Graham (1943)

Manifesto of the Anarchist Federation on War (1943)

The Yankee Peril, by Marie Louise Berneri (1943)

Manifesto of the Anarchist Federation of Britain (1939)

Tribunals and Political Objectors, by Albert Meltzer and Vernon Richards (1940)

The Black Spectre of War, by Emma Goldman (1938)

Anti-War Manifesto, by the Anarchist International (1915)

Between Ourselves, by Emidio Recchioni (1915)

The Last War, by George Barrett (1915)

Have the Leopards Changed Their Spots?, by Thomas H. Keell (1914)

Correspondence on Kropotkin’s Letter to Professor Steffen, by Fred W. Dunn (1914)

Anti-Militarism: Was It Properly Understood?, by Errico Malatesta (1914)

The Conscripts Strike, by Louise Michel (1881)

If We Must Fight, Let’s Fight for the Most Glorious Nation, Insubordination

Black Flag Anarchist Review Vol. 4 No. 3, World War or Class War (Autumn 2024)

Anti-Militarism section of the Kate Sharpley Library website