Published in the book, ‘Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Scientific Basis as Defined by Some of Its Apostles’, by Albert Parsons, published by Lucy E. Parsons in 1887

Under the deep shadow of that awful tragedy, enacted on the eleventh day of November [1887], many shameful deeds passed almost unnoticed; the gloom, so dense that the close of the century will scarcely see it lightened, veiled the blackness of injustices that would have appalled the hearts of the people if thrown up against the light of freedom in brighter days. Now, it is well that they be brought forth for investigation; the judgment of the people must be given on proceedings done in the name of “law and order,” in this so-called free country.

It will be remembered that in the extras of Friday Nov. 11th a casual notice of the arrest of Mrs. [Lucy E.] Parsons “for persistent disobedience of orders,” and that of a lady friend for haranguing the people” was given. The officers were reported as being “very courteous and gentle,” and the ladies “were given arm-chairs in the registry office merely to keep them away from the crowd and prevent trouble.”

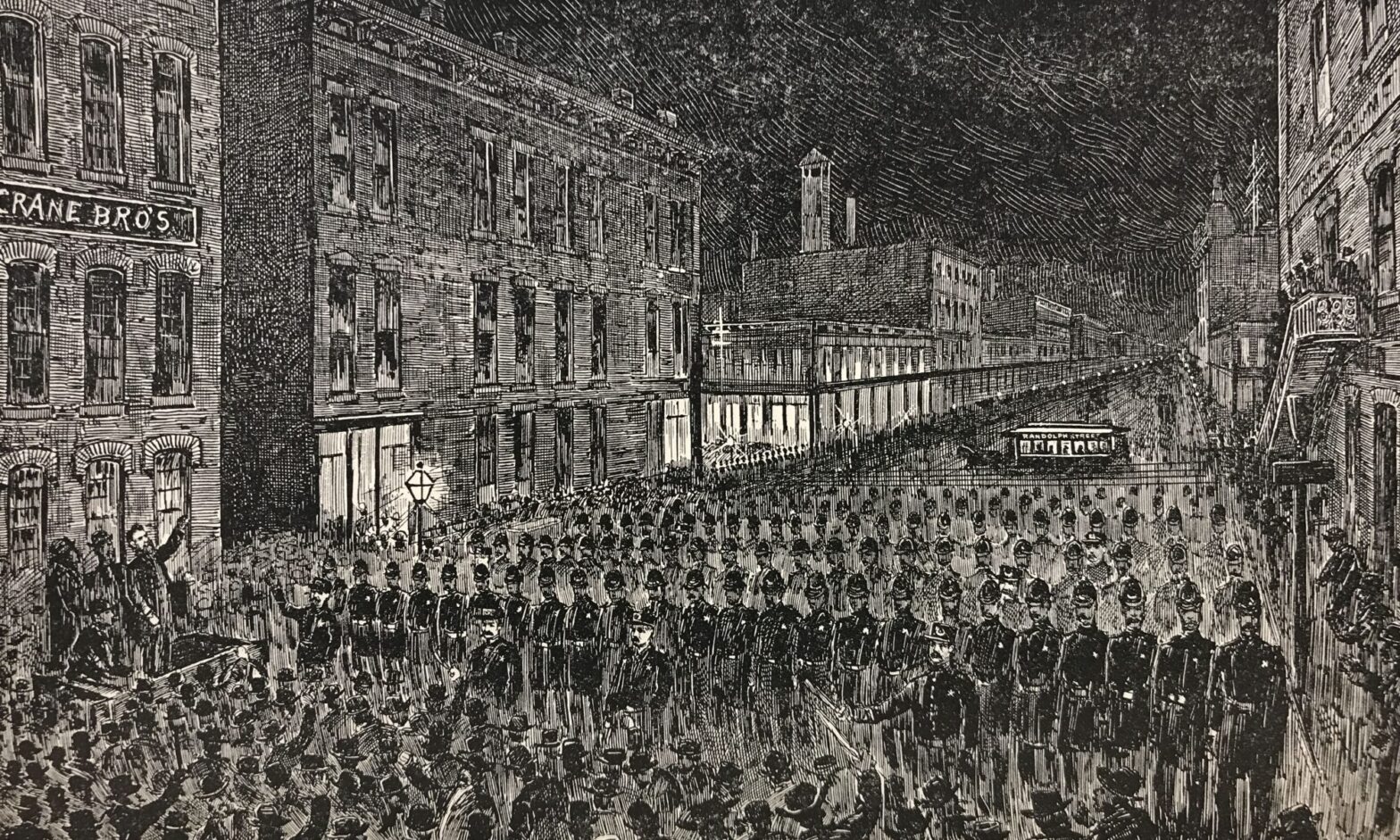

This is the true story: On Thursday evening after Governor Oglesby’s tardy decision had been given, Mrs. Parsons accompanied by Mr. Holmes and myself, went to the jail to plead for a last sad interview. She was denied an entrance, but was told by the deputy-sheriff in charge that she would be admitted at half-past eight the following morning. At that time she, with her children and myself was promptly as near to the gates as the police would permit. Every street for two blocks away leading towards the jail was crossed by a rope and guarded by a line of police armed with Winchester rifles. At the first corner Mrs. Parsons quietly made known her errand. The lieutenant said she could not get in there, but that she should pass on to the next corner, and the officer there would perhaps let her through.

She did so with the same result. Another captain told her she must get an order from the sheriff; on inquiring where he could be found, she was told to go on to another corner where a message might be sent to him. At this corner no one knew anything about it and again we were sent on; and so, for more than an hour we were urged along in a veritable game of “Pussy wants a corner” that would have been ridiculous had it not been so tragical. Sometimes it was a deputy sheriff who was to be found at a certain corner, sometimes it was the peculiarity of location that promised an entrance beyond the death-line; but it was always “not this corner but some other corner.” Not once did an officer say, “you positively cannot see your husband. You are forbidden to enter his prison and bid him farewell,” but always offered the inducement that if she passed quietly along, at some indefinite point she would be admitted.

Meanwhile the precious moments were flying; sweet little Lulu’s face was blue with cold, and her beautiful eyes were swimming with tears. Manly little Albert, too, was shivering in the raw atmosphere, as he patiently followed his grief stricken mother from one warlike street to another.

Then Mrs. Parsons besought the officers only to take the children in for their father’s last blessing and farewell; for one last interview that his memory might never be effaced from their young and impressible minds; one last look that the image of that noble father might dwell forever in their heart of hearts; one moment in which to listen to the last dear words that his loving and prophetic soul might dictate to the darling children left to live after him. In vain. The one humble prayer the brave woman ever voiced to the authorities in power, was denied her. They heeded her not except to hurry her along.

The last sad moments of her dear one’s life were wasting so steadily, so relentlessly. Who can picture her agony? Who can wonder at her desperate protest against the “regulations of the law” which were killing her husband and forbidding her approach. She determinedly crossed the death line and told them “to kill her as they were murdering her husband.” No, they were not so merciful. They dragged her outside, inveigled her around to a (quieter corner, with the promise of “seeing about it,” and there ordered her, her two children and myself into a patrol wagon awaiting us. What had the innocent children done?

Pleaded dumbly with soft, tearful eyes for their father. What was my crime? Faithfulness to a sorrowing sister.

Once when some one asked me if I could not “prevail on that woman to keep quiet and go home,” I had answered :

“I have no such influence over her and would not exert it if I had. Do you wonder that she is nearly distracted with grief at being driven from pillar to post like this, when in one short hour her husband will be dead? She has not seen him for five days, and now they deny her the sacred right of a last good bye; why the worst despotisms in Europe are not so bad as that.”

At this a burly brutal-looking detective in citizen’s clothes said:

“See here young woman! You shut up or we will send you off in the wagon!”

“Must I not even say this much, in a free country?” I asked in surprise.

“No, you can’t,” he growled, with a fierce frown.

And this, I suppose, constituted “my harangue to the people on the streets.”

And so, into the patrol we were hustled, a heart-broken wife and mother, two innocent tearful children, and the one friend near her. The “polite” officers did not perhaps go out of their way to be brutal or rough, but were about as “courteous” as so many wooden men moving about like machines. Far from being given arm chairs in a comfortable office, we were locked up in dark, dirty stone cells — Mrs. Parsons and her children in one, myself in another.

And there — shame be it to America that I have it to relate! There we were stripped to the skin and searched! Even the children, crying with fright, were undressed and carefully searched.

No excuse could be offered that we were ignorant foreigners and did not understand the laws of the country, and that the safety of American institutions depended on our being totally unarmed; for the blood of revolutionary forefathers coursed in our veins, while the matron and officers who gave the order (if there be any merit in being born in one country rather than another) had not been here long enough to speak our language correctly.

The woman ran her fingers through my hair, through the hems of my skirts, the gathers of my undergarments, even to my stockings; I asked her “what she expected to find.”

“I don’t know,” she simpered, “this is my duty.”

She clanged the doors behind her finally and we were left alone. We could hear each other’s voices but could not see one another. And in those gloomy, underground cells we passed those terrible, anxious hours of Friday, Nov. 11, 1887.

God knows her lot would have been bitter enough in her own comfortable home, with loving, sympathizing friends at her side to support her in that awful time. But who dare dwell upon the reality — the picture of that devoted wife in such a place at such an hour?

At a few minutes past twelve the matron came, and said coldly “It is all over,” and left us.

Not a soul came and asked the bereaved women if they could help her to even a cup of cold water. And I, the one friend near her, could only sit shivering with my face pressed to the cruel iron bars, listening to her low, despairing moans, as helpless as herself.

Every friend who called to inquire after our whereabouts and welfare was sent away without any information and we were not told that anyone had been to see us.

Mr. Holmes came as early as he received word that we had been arrested, and was not only denied any information, but was roughly ordered away and threatened with arrest himself “if he hung around there.”

At three o’clock Capt. Schaack came down and asked how long we had been there, hypocritically expressed sorrow that we had been locked up, and opened our prison doors. They had done their worst and Mrs. Parsons was permitted to go to her desolated home.

And thus it was that while organized authority was judicially murdering the husband and strangling “the voice of the people,” the wife and children were locked up in a dungeon, that no unpleasant scene might mar the smoothness of the proceedings. Where is there a parallel in history? Only in the state where dying men are forbidden to speak a few last words can such a scene be possible.

Lizzie M. Holmes

Also

Lizzie M. Holmes (also known as Swank) texts at the Anarchist Library

[Incomplete] works by Lizzie M. Holmes [also known as Swank]

Lucy E. Parsons texts at The Anarchist Library

Black Flag Anarchist Review, Vol.3, No.2, Summer 2023 (featuring ‘Anarchy in the USA’)

A Martyr, from The Alarm (1885)

“Timid” Capital, by Lizzie M. Swank (1886)

Abolition of Government, by Lizzie M. Swank (1886)

Law vs Liberty, by Albert Parsons (1887)

Life of Albert R. Parsons, by Lucy E. Parsons (1889)

A Reminiscence of Charlie James, by Honoré J. Jaxon (1911)

The Haymarket Martyrs, by Lucy E. Parsons (1926)

Anarchists and the Wild West, by Franklin Rosemont (1986)

Autobiographies of the Haymarket martyrs

The Haymarket Tragedy, by Paul Avrich

Haymarket Scrapbook, edited by Franklin Rosemont and David Roediger