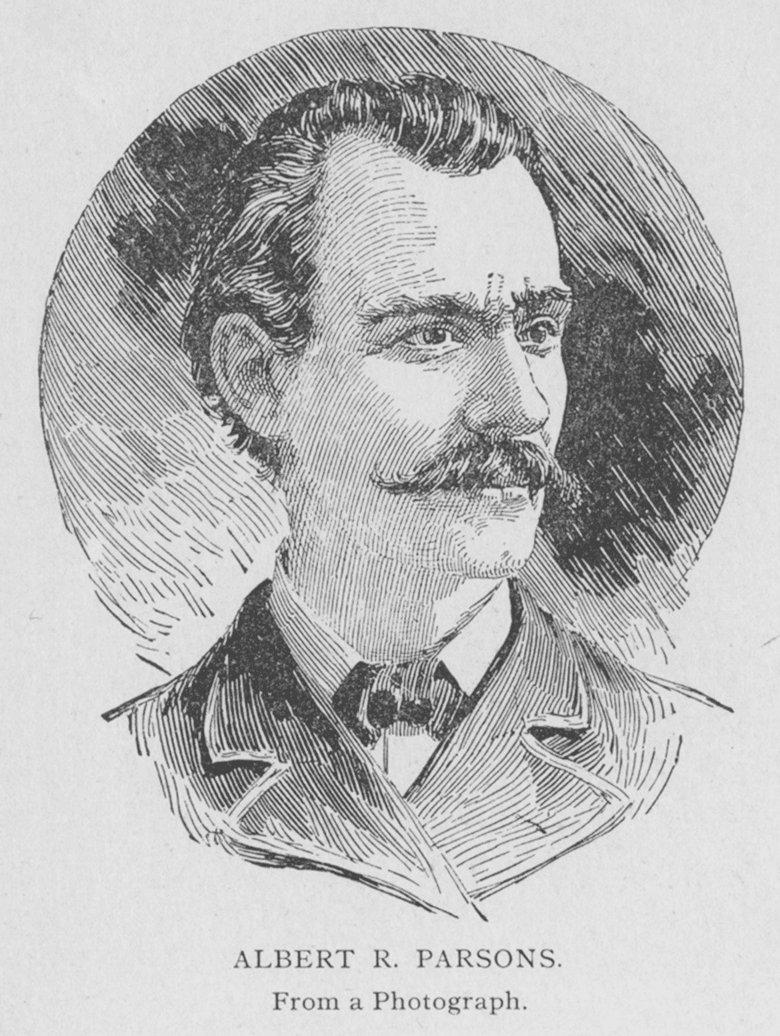

From ‘Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Scientific Basis as Defined by Some of Its Apostles’, by Albert Parsons, published by Lucy E. Parsons in 1887

It will be comprehended by the thoughtful reader, who has perused these pages thus far, that the popular conception of anarchism is a mistaken one. An insane anger against personal tyrants, and a vague desire to destroy and kill, are not the characteristics of the philosophy known as anarchy, as a majority of the people up to this time have been led to believe.

The philosophy of anarchism is included in the one word “Liberty;” yet it is comprehensive enough to include all things else. No barriers whatever to human progression, to thought, or investigation, are placed by anarchism; nothing is considered so true or so certain, that future discoveries may not prove it false; therefore, it has but one infallible, unchangeable motto, “Freedom.” Freedom to discover any truth, freedom to develop, to live naturally and fully. Other schools of thought are composed of crystallized ideas — principles that are caught and impaled between the planks of long platforms, and considered too sacred to be disturbed by a close investigation. In all other “issues” there is always a limit; some imaginary line beyond which the searching mind dare not penetrate, lest some pet idea melt into a myth. Science has been merciless and without reverence, because it is compelled to be: the discoveries and conclusions of one day are exploded by the discoveries and conclusions of the next. But anarchism is the usher of science — the master of ceremonies to all forms of truth. It would remove all barriers between the human being and natural development. From the natural resources of the earth, all artificial restrictions, that the body might be nurtured, and from universal truth, all bars of prejudice and superstition, that the mind may develop harmoniously.

It is then the complete opposite of ideas of force and violence. Force, in invading the rights of individuals, is entirely repudiated; legalized, national force as well as the irresponsible force of the individual. “How then,” perhaps the inquirer, even at this stage, may ask, “do you reconcile your advocacy of a violent revolution with so peaceful a philosophy ?”

That force will be used in the coming change, whether we advocate it or not, is quite evident to students of history; that there is a reconcilable reason for our advising people to be ready for it, is shown in the constant use of force that is necessary to maintain the present so-called “order,” but actual disorder. Every institution which now works injustice to human kind is possible only through the violence or threats of violence that are continually exerted. Well-filled armories and well-drilled regiments are the pillars of class rule, and monopoly rests on the strength of courts and constabulary.

Force (legalized) invades the personal liberty of man, seizes upon the natural elements, and intervenes between man and natural laws; from this exercise of force through governments flows nearly all the misery, poverty, crime and confusion existing in society. So, we perceive, there are actual, material barriers blockading the way. These must be removed. If we could hope they would melt away, or be voted or prayed into nothingness, we would be content to wait and vote and pray. But they are like great frowning rocks towering between us and a land of freedom, while the dark chasms of a hard-fought past yawn behind us. Crumbling they may be with their own weight and the decay of time, but to quietly stand under till they fall is to be buried in the crash. There is something to be done in a case like this — the rocks must be removed. Passivity while slavery is stealing over us is criminal. For the moment we must forget that we are anarchists — when the work is accomplished we may forget we were revolutionists.

And what of the glowing beyond that is so bright that the Grad-grinds say it is a dream? It is no dream, it is the real, stripped of brain-distortions materialized into thrones and scaffolds, mitres and guns. It is nature acting on her own interior laws as in all her other associations. It is a return to first principles; for were not the land, the water, the light all free before governments took shape and form? In this free state we will again forget to think of these things as “property.” It is real, for we, as a race, are growing up to it. The idea of less restriction and more liberty, and a confiding trust that — nature is equal to her work, is permeating all modern thought. From the dark years — not so long by — when it was generally believed that man’s soul was totally depraved and every human impulse bad; when every action, ever thought, and every emotion was controlled and restricted; when the human frame, diseased, was bled, dosed, suffocated and kept as far from nature’s remedies as possible; when the mind was seized upon and distorted before it had time to evolve a natural thought — from those days to these latter years the progress of this idea has been swift and steady. It is becoming more and more apparent that in every way we are “governed best where we are governed least.”

Still unsatisfied perhaps, the inquirer seeks for details, for ways and means, and whys and wherefores. How will we go on like human beings eating and sleeping, working and loving, exchanging and dealing, without government. So used have we become to “organized authority” in every department of life that ordinarily we cannot conceive of the most common-place avocations being carried on without their interference and “protection.” But anarchism is not therefore compelled to outline a complete organization of a free society. To do so with any assumption of authority would be to place another barrier in the way of coming generations. The best thought of to-day may become the useless vagary of to-morrow, and to crystallize it into a creed is to make it an unwieldy obstacle as well. Still we may prophesy and conjecture, and while we believe no great principle is compromised if we say “let the coming freemen take care of themselves,” we may judge from our present knowledge of human characteristics and the action of natural law something of what future societary arrangements will be. “We can judge of the future only by the past.” We can believe it is only necessary to remove the barriers, to abolish the powers that force man into unnatural channels, to recognize no “organized authority,” and believe — that new systems will spring spontaneously from the spirit of the times, and the conditions surrounding the social units — yet we may have logical conceptions of societary arrangements, and the wisdom to give them to inquirers.

We judge from experience that man is a gregarious animal, and instinctively affiliates with his kind — co-operates, unites in groups, works to better advantage, combined with his fellow workmen than when alone. This would point to the formation of co-operative communities, of which our present trades-unions are embryonic patterns. Each branch of industry will no doubt have its own organization, regulations, leaders, etc.; it will institute methods of direct communication with every member of that industrial branch in the world, and establish equitable relations with all other branches. There would probably be conventions of industry which delegates would attend, and where they would transact such business as was necessary, adjourn and from that moment be delegates no longer, but simply members of a group. To remain permanent members of a continuous congress would be to establish a power that is certain sooner or later to be abused.

No great central power, like a congress consisting of men who know nothing, of their constituents’ trades, interests, rights or duties, would be over the various organizations or groups; nor would they employ sheriffs, policemen, courts or jailors to enforce the conclusions arrived at while in session. The members of groups might profit by the knowledge gained through mutual interchange of thought afforded by conventions if they choose, but they will not be compelled to do so by any outside force.

Vested rights, privileges, charters, title deeds, upheld by all the paraphernalia of government — the visible symbol of power — such as prisons, scaffolds and armies will have no existence. There can be no privileges bought or sold, and the transaction kept sacred at the point of the bayonet. Every man will stand on an equal footing with his brother in the race of life, and neither chains of economic thralldom nor mental drags of superstition shall handicap the one to the advantage of the other.

Property will lose a certain attribute which sanctifies it now. The absolute ownership of it — “the right to use or abuse” will be abolished — and possession, use, will be the only title. It will be seen how impossible it would be for one person to “own” a million acres of land, without a title, deed backed by a government ready to protect that title at all hazards, even to the loss of thousands of lives. He could not use the million acres himself, nor could he wrest from its depths the possible resources it contains. The accidental discovery of a coal field or a gas well could not as now make one man enormously rich in a moment, the arbiter and master of several hundred lives, who, robbed of their own rightful inheritance, are entirely dependent on the will of the lucky man. There will be no law, of course, to prevent his hiring men to work for him, but as every man will have an equal chance at mother earth, the probabilities are that they will have too much business of their own to be hired.

The division of labor now developing in the field of production already illustrates the benefits of co-operative efforts, and it is quite evident that future production will be carried on in this line. Communities and groups will form, and in the interests of those concerned will make their regulations. All organization will be voluntary with the sacred right forever reserved to each individual “to think and to rebel.” “But this will create chaos and eternal confusion!” the objector will say. Why should it? It has been seen even under present systems that liberty of action is a great civilizer. One learns by observation that it is not the restraints thrown around the individual by laws and religious creeds, that make him “good.” Often the removal of these very restrictions renders him surprisingly manful and upright, feeling that he is not forced into a path he would tread naturally, if let alone. It was thought not long ago by nearly all, that to destroy the belief in an everlasting hell would be to break the bonds which held in check millions of wicked people ready to plunge into every species of evil, like a torrent raging onward to its own destruction. There is a benighted old journal still existing in these latter days which teaches that “hell and the scaffold are the civilizers of the people.” The dear good old lady with one of the kindest hearts in the world, who said, “If I didn’t believe in the everlasting punishment of eternal fires, I would do all sorts of wicked things, steal, lie, murder, dissipate,” should become its editor.

The belief in a literal place of torment has nearly melted away; an and instead of the direful results predicted, we have a higher and truer standard of manhood and womanhood. People do not care to go to the bad when they find they can as well as not. Individuals are unconscious of their own motives in doing good. While acting out their natures according to their surroundings and conditions, they still believe they are being kept in the right path by some outside power, some restraint thrown around them by church or state. So the objector believes that with the right to rebel and secede sacred to him, he would forever be rebelling and seceding, thereby creating constant confusion and turmoil. Is it probable that he would, merely for the reason that he could do so? Men are to a great extent creatures of habit, and grow to love associations; under reasonably good conditions, he would remain where he commences; and if he did not, who has any natural right to force him into relations distasteful to him? Under the present order of affairs, persons do unite with societies and remain good, disinterested members for life where the right to retire is always conceded. The final outcome, many disciples of anarchism believe will be communism — the common possession of the resources of life and the productions of united labor. No anarchist is compromised by this statement, who does not reason out the future outlook in this way; the many of us who do, are responsible only for our own opinions on the subject.

Many expedients will be tried by which a just return may be awarded the worker for his exertions. The time check or labor certificate, which will be honored at the store-houses hour for hour, will no doubt have its day. But the elaborate and complicated system of bookkeeping this would necessitate, the impossibility of balancing one man’s hour against another’s with accuracy, and the difficulty in determining how much more one man owed to natural resources, conditions, and the studies and achievements of past generations, than did another, would, we believe, prevent this system from obtaining a thorough and permanent establishment. The mutual banking system outlined by W. B. Greene may be in operation in the future free society. Another system, more simple, to the writer appears the most acceptable and likely to prevail, Members of the groups will carry cards, showing their standing in their respective societies, and if honest producers, they will be honored in any other group they may visit, and given whatever is necessary to their welfare and comfort.

But, after all, as we grow more enlightened under this “larger liberty” we will grow to care less and less for that exact distribution of material wealth, which, in our greed-nurtured senses, seems now so impossible to think upon carelessly. The men and women of loftier intellects, in the present, think not so much of the riches to be gained by their efforts as of the good they can do. There is an innate spring of healthy action in every human being who has not been crushed and pinched by poverty and drudgery from before his birth, that impels him onward and upward. He cannot be idle, if he would; it is as natural for him to develop, expand, and use the powers within him when not repressed as it is for the rose to bloom in the sunlight and fling its fragrance on the passing breeze. The grandest works of the past were never performed for the sake of money. Who can measure the worth of a Shakespeare, an Angelo or Beethoven in dollars and cents? Agassiz said “he had no time to make money,” there were higher and better objects in life than that. And so will it be when humanity is once relieved from the pressing fear of starvation, want, and slavery, it will be concerned, less and less, about the ownership of vast accumulations of wealth. Such possessions would be but an annoyance and trouble. When two or three or four hours a day of easy, of healthful labor will produce all the comforts and luxuries one can use, and the opportunity to labor is never denied, people will become indifferent as to who owns the wealth they do not need. Wealth will be below par, and it will be found that men and women will not accept it for pay, or be bribed by it to do what they would not willingly and naturally do without it. Some higher incentive must, and will, supersede the greed for gold. The involuntary aspiration born in man to make the most of one’s self, to be loved and appreciated by one’s fellow-beings, to “make the world better for having lived in it,” will urge him on to nobler deeds than ever the sordid and selfish incentive of material gain has done.

If, in the present chaotic and shameful struggle for existence, when organized society offers a premium on greed, cruelty, and deceit, men can be found who stand aloof and almost alone in their determination to work for good rather than gold, who suffer want and persecution rather than desert principle, who can bravely walk to the scaffold for the good they can do humanity, what may we expect from men when freed from the grinding necessity of selling the better part of themselves for bread? The terrible conditions under which labor is performed, the awful alternative if one does not prostitute talent and morals in the service of mammon; the power acquired with the wealth obtained by ever so unjust means, combine to make the conception of free and voluntary labor almost an impossible one. And yet, there are examples of this principle even now. In a well-bred family each person has certain duties, which are performed cheerfully, and are not measured out and paid for according to some pre-determined standard; when the united members sit down to the well-filled table, they do not scramble to get the most, while the weakest do without, or gather greedily around them more food than they could possibly consume. Each patiently and politely awaits his turn to be served, and leaves what be does not want; he is certain that when again hungry plenty of good food will be provided.

Again, the utter impossibility of awarding to each an exact return for the amount of labor performed will render absolute communism a necessity sooner or later. The land and all it contains, without which labor cannot be exerted, belong to no one man, but to all alike. The inventions and discoveries of the past are the common inheritance of the coming generations; and when a man takes the tree that nature furnished free, and fashions it into a useful article, or a machine perfected and bequeathed to him by many past and succeeding generations, who is to determine what proportion is his and his alone? Primitive man would have been a week fashioning a rude resemblance to the article with his clumsy tools, where the modern worker has occupied an hour. The finished article is of far more real value than the rude one made long ago, and yet the primitive man toiled the longest and hardest. Who can determine with exact justice what is each one’s due?

There must come a time when we will cease trying. The earth is so bountiful, so generous; man’s brain is so active, his hands so restless, that wealth will spring like magic, ready for the use of the world’s inhabitants. We will become as much ashamed to quarrel over its possession as we are now to squabble over the food spread before us on a loaded table.

“But all this,” the objector urges, “is very beautiful in the far-off future, when we become angels. It would not do now to abolish governments and legal restraints; people are not prepared for it.”

This is a question. We have seen, in reading history, that wherever an old-time restriction has been removed the people have not abused their newer liberty. Once it was considered necessary to compel men to save their souls, with the aid of governmental scaffolds, racks and stakes. Until the foundation of the present republic, it was considered absolutely essential that governments should second the efforts of the church in forcing people to attend the means of grace; and yet it is found that the standard of morals among the masses is raised since they are left free to pray as they see fit, or not at all, if they prefer it. It was believed the chattel slaves would not work if the overseer and whip were removed; they are so much more a source of profit now that ex-slave owners would not return to the old system if they could.

So many of the able writers quoted in this book have shown that the unjust institutions which work so much misery and suffering to the masses have their root in governments, and owe their whole existence to the power derived from government, we cannot help but believe that were every law, every title deed, every court, and every police officer or soldier abolished to-morrow with one sweep, the people would be better off than now. The actual, material things that man needs would still exist; his strength and skill would remain and his instinctive social inclinations retain their force. Freed from the systems that made him wretched before, he is not likely to make himself more wretched for lack of them. Much more is contained in the thought that conditions make man what he is, and not the laws and penalties made for his guidance, than is supposed by careless observation. We have laws, jails, courts, armies, guns and armories enough to make saints of us all, if they were the true preventives of crime; but we know they do not prevent crime; that wickedness and depravity exist in spite of them, nay, increase as the struggle between classes grows fiercer, wealth greater and more powerful, and poverty more gaunt and desperate. As an illustration of this truth, notice the statistics of Warden McClaughrey, given before the Union League Club of Chicago, a club consisting of millionaires. He stated that 500,000 criminals in the United States, according to the best obtainable statistics, are under 21 years of age!

What an army of outcasts! Does any one believe that these young persons deserted peaceful and virtuous walks of life, blessed with love, home and friends, voluntarily? Or, were they not crowded to the prison doors by the wretched surroundings the present civilization forces upon them? Prisons the guardians of the people’s morals? The above showing damns forever this idea!

Have we not good reason to believe that the entire abolition of a centralized power, with all its facilities for granting privileges, for protecting monopolies and aiding robbers in stealing the people’s inheritance, would result in great good to humanity, bad as it is become through long ages of injustice?

Oh, Liberty! No wonder the vision of thy realization is too bright to be deemed more than a fleeting dream! The weary toiler who now never thinks of rest, dare not look upon the picture, the sensuous idler scorns it. But how possible after all! Nature has denied us not one element towards its realization — man himself lacks not one faculty towards its appreciation and enjoyment. To know that little children will no more drudge and wither away in factories and mines; that women will not slowly coin their heart’s blood over their needle, while starvation eternally stares in at the door, that strong men will not waste their lives in abject slavery or unwilling vagabondage, and that constant. fear of cold and hunger and homelessness that so petrifies and stupifies the heart and soul will be banished forever; that women will be freed from the black clinging trail of the serpent winding through all ages, the selling of herself for bread or splendor; that genius will, no longer crushed in the narrow, suffering limits of neglect and poverty, rise to heights unknown before — is it not worth working, living and dying for? Ah, no, friends, anarchy is not buried — it is not dead.

Also

To the Workingmen of America, by the International Working Peoples’ Association (1883)

The Indians, from The Alarm (1884)

The Black Flag, from The Alarm (1884)

A Martyr, from The Alarm (1885)

“Timid” Capital, by Lizzie M. Swank (1886)

Abolition of Government, by Lizzie M. Swank (1886)

Plea for Anarchy, by Albert Parsons (1886)

The Famous Speeches of the Eight Chicago Anarchists in Court (1886)

Autobiographies of the Haymarket Martyrs (1886-1889)

Arrest of Mrs. Parsons and Children, by Lizzie M. Holmes (1887)

The Philosophy of Anarchism, by Albert Parsons (1887)

Law vs Liberty, by Albert Parsons (1887)

Before the Storm, by Peter Kropotkin (1888)

Reconstruction in Texas, by Albert Parsons (1889)

Life of Albert R. Parsons, by Lucy E. Parsons (1889)

A Piece of History, by Lucy E. Parsons (1895)

Lucy E. Parsons’ Speeches at the Founding Convention of the Industrial Workers of the World (1905)

A Rebel May Day, from Industrial Worker (1909)

The Trial a Farce, by Lucy E. Parsons (1911)

A Reminiscence of Charlie James, by Honoré J. Jaxon (1911)

The Haymarket Martyrs, by Lucy E. Parsons (1926)

The Haymarket Tragedy, by Paul Avrich (1984)

Black Flag Anarchist Review, featuring ‘Anarchy in the USA’, Summer 2023