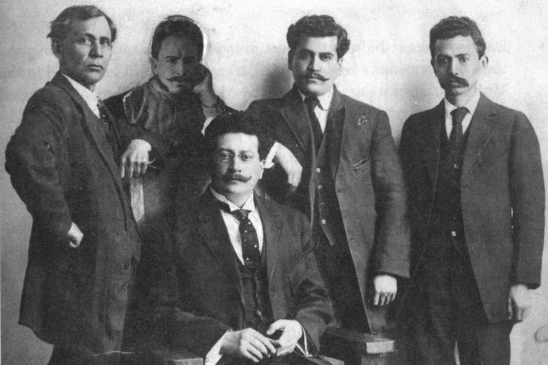

Anselmo Figueroa, Práxedis Guerrero, Ricardo Flores Magón, Enrique Flores Magón, and Librado Rivera (Junta Organizadora del Partido Liberal Mexicano)

From ‘Cienfuegos Press Anarchist Review’, Number 5, 1980, Over the Water, Sanday, Orkney

Of the many comrades and collaborators of Ricardo Flores Magon, Librado Rivera was by far the closest. Their revolutionary partnership lasted twenty years, rivalling that of Durruti and Ascaso, and only ended with Ricardo’s death in Leavenworth Prison, murdered directly or indirectly by the U.S. authorities. Librado was a founding member of the Partido Liberal Mexicano and made a fundamental and major contribution to its anarchist orientation. Despite this, though, Librado has been badly neglected on his own account. This may be in part due to his own natural modesty and reticence, as he always shunned the limelight while remaining at the same time in the forefront of the struggle, preferring to adopt the role of a seemingly ‘simple militant’. He was, in reality, far from this. As a tireless anarchist revolutionary and propagandist he spent more than thirty years fighting, as he would say, ‘in favour of all the oppressed and exploited of the earth’ in order to establish ‘a new society which would have as well as liberty, love and justice for all!’ 1

Librado Rivera was born in the municipality of Rayon, San Luis Potosi state in 1864, the son of a poor landholding farmer. In his early years he attended an open air school held on the nearby ‘La Estancita’ hacienda. The teacher of this school, Jesus Sanaz, was to have a great influence on Librado, as after school pupil and teacher would go on long walks together where Sanaz would explain to the young Librado the reasons for the poverty of the peasants and the need for radical social reform. Later he moved to the municipal school at Rayon. Here Librado proved to be an exceptional pupil, and through the intervention of a local hacienda owner he managed to obtain a scholarship from the state government which enabled him to continue his studies at the Escuela Normal de Maestros in San Luis Potosi, the state capital.

Graduating with honours from the Escuela Normal in 1888, Librado began to teach at the Escuela ‘El Montecillo’ in San Luis Potosi, becoming its director some years later. In 1895 he returned to the Escuela Normal as professor of history and geography. To supplement his wages as a teacher, he became, in his spare time, a private tutor to the children of San Luis Potosi’s most elite families, including those of the local jefe politico. While visiting the homes of the provincial bourgeoisie Librado had ample time to compare their pampered lives of wealth and idleness with the poverty and injustice of the lives of the small landowners and peons. This odious spectacle of the rich living off the labour and suffering of the poor was to haunt Librado throughout the rest of his life. Soon he began to denounce social injustice to his pupils at the Escuela Normal.

“The money I received as salary”, he later wrote, “came from the wretched purses of the people in the form of taxes. My responsibility to the people therefore was greater than my responsibility to the government, because a government cannot be changed overnight by the popular will. Obeying then, this cry from my conscience, I began to fight the dictatorship as much from within my Profession as outside it…” 2

One student he was to influence through this was Antonio I. Villarreal, who later became a fellow member of the PLM’s Organizing junta.

In 1900 Librado became an enthusiastic supporter of the newly formed Liberal movement. The initial aim of this movement, founded through the initiative of Camillo Arriaga, was to combat the growing influence of the catholic church in State affairs despite the Reform laws of 1857; but many of those attracted to the movement were, as Librado himself, bitterly opposed to the Diaz dictatorship, based as it was on slavery, corruption and State expropriation of lands communally owned by villages where the peasants worked them in a form of primitive anarchist-communism.

In February of the following year Librado represented the Club Liberal ‘Benito Juarez’ of Rayon, one of over a hundred such clubs to be formed throughout the country, at the first Congress of Liberal Clubs held in San Luis Potosi. It was at this congress that he first met Ricardo Flores Magon, whose fearless speech openly denouncing the Diaz administration as a den of thieves Librado wholeheartedly endorsed.

Following the Congress Librado continued to teach at the Escuela Normal, whose director he had now become, while actively participating in the running of the Club Liberal ‘Ponciano Arriaga’ of San Luis Potosi as one of its secretaries. Through his contact with the club’s president, Camillo Arriaga, Librado discovered for the first time the works of Bakunin, Kropotkin and other anarchist writers which he read with enthusiasm and passion, borrowing the books (which were at that time not openly available in Mexico) from Arriaga’s extensive library.

Towards the end of 1901 the Club Liberal ‘Pociano Arriaga’, which served as the direction centre for all the Liberal clubs throughout the country, began preparations for a Second Liberal Congress, which was to be held, as the first, in San Luis Potosi. This was to be held despite the dictatorship’s mounting repression against the liberal , which had resulted in the suppression of many clubs and the imprisonment of activists including Ricardo and Jesus Flores Magon and the banning of their opposition newspaper Regeneracion.

This Second Congress though intended to go far beyond the mere anti-clericalism of the first. The proposed agenda, which no doubt Librado helped to draft, included items on the freedom of the press, the freedom of suffrage, the suppression of the jefes politicos and methods for the improvement of the workers’ conditions on the large haciendas. However, the Congress was never to be held. On January 24th, 1902, less than two weeks before the congress was due to Start, a meeting of the Club Liberal ‘Ponciano Arriaga’ was brutally broken up by the police and its members arrested after a disturbance had been provoked by the porfirista congressman and plain clothes policemen.

Librado and Arriaga managed to avoid immediate arrest in the meeting hall by taking refuge in Arriaga’s house, but when this was surrounded by rurales and a detachment of regular soldiers the two were forced to give themselves up. Taken to the state penitentiary, they were accused, together with Juan Sarabia the editor of the club’s newspaper Renecimiento, of ‘obstructing public officials in the exercise of their duties’ and sentenced to one year’s imprisonment without even the formality of a trial.

While in prison Librado, Sarabia and Arriaga, now joined by Antonio Diaz Soto y Gama, continued their work for the Liberal movement by founding the newspaper El Demofilio, which was printed in San Luis Potosi by Arriaga’s cousin. El Demofilio was launched on behalf of “workers who are victims of injustices … the humble and exploited classes” and attacked many aspects of the Diaz dictatorship including the use of forced military conscription, the Leva, as a slave labour system. Librado himself contributed many articles to the newspaper on the social question. This proved to be too much for the dictatorship, and after only four months El Demofilio was forced to close down. Librado and his four comrades were moved into separate cells and held incommunicado for several months. In addition the authorities had the penitentiary surrounded by federales and placed extra guards outside the four liberals’ cells. It was while in prison that Librado was given the nickname El Fakir because of his great powers of concentration. He would sit in the corner of the cell he shared with his three comrades and read, completely oblivious to what was going on around him, much to the annoyance of his cell-mates.

At the end of September 1902 Librado was released from prison, and after spending some time, possibly in San Luis Potosi, made his way to Mexico City, arriving there in March 1903 he immediately joined Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magon and Juan Sarabia, who had been released at the same time as himself, on the editorial staff of El Hijo del Ahuizote, the successor of the banned Regeneracion. Barely one month after his arrival in Mexico City though, the offices of El Hijo del Ahuizote were raided by the police, and Librado, together with Ricardo, Enrique, Sarabia and six other comrades were arrested for “contempt of public officials”. Taken to the infamous Belem prison where they were all held incommunicado for two and a half months, Librado, for some unknown reason, was then released and went into hiding, while the others stayed on in prison until the following October.

Upon their release from prison, the most prominent activists in the anti-Diaz Opposition decided to continue the struggle from exile rather than endure more years of useless reclusion. In early 1904 therefore, Ricardo and Enrique crossed the border into the United States and went to Laredo, Texas, where Librado joined them soon after, together with three other comrades including his former student from San Luis Potosi’s Escuela Normal, Antonio I. Villearreal.

Here Librado found work as a labourer, as did the other exiles, with the intention of raising enough funds to republish Regeneracion. In the middle of the year however, Ricardo was forced, through harassment by Diaz agents, to move to St. Louis, Missouri. Soon he was joined by Librado who now participated fully in the running of Regeneracion. In St. Louis Librado joined Ricardo in attending meetings held by Emma Goldman and also became friendly with a Spanish anarchist, Florencio Bazora. Both these contacts were to make a profound impact on Librado and Ricardo equally, helping a great deal to clarify their anarchism.

On September 18th, 1905 the Junta Organizadora del Partido Liberal Mexicano was formed by the Liberal exiles with Ricardo as president and Librado as the first of the three committeemen (vocal). Less than a month after the founding of the PLM Junta the offices of Regeneracion were raided by Pinkerton detectives who arrested Ricardo, Enrique and Juan Sarabia, and confiscated all the office equipment including the printing presses. Mainly through the sacrifice of all the comrades involved Regeneracion managed to appear again in February 1906, but the following month Ricardo and his two comrades who had been released on bail, were forced to flee to Canada, fearing, not without justification, that the U.S. authorities intended to extradite them to Mexico. Now the editorship was taken up by Librado with the help of Manuel Sarabia (the brother of Juan), Villarreal and the newspaper typesetter Aaron Lopez Manzano.

In September however, the new offices of Regeneracion were raided by the police who this time smashed up the printing pliant. A month later the homes of Librado and Manzano were raided early in the morning by federal police and immigration officers and the two men arrested. Taken secretly to prison Librado was accused by the Diaz dictatorship of “robbery and murder” during the miners strike at Canania, Sonora that had taken place the previous June. After being held incommunicado for some time in St. Louis jail, the two comrades were put on a train for Mexico and deportation. Thanks, however, to a public outcry instigated by two St. Louis newspapers, the St. Louis Post Dispatch and the St. Louis Globe Democrat, started when the plight of Librado’s and Manzano’s families became known, the authorities were forced to abandon their attempt at illegal and clandestine deportation. Instead the two-men were taken off the train at Ironton.

Even here they were held incommunicado in the local jail, the U.S. authorities always willing to do the dirty work of Diaz, obviously hoping that the campaign to free the two men would blow itself out. They were sorely mistaken though. The two newspapers continued relentlessly until the two men were returned to St. Louis. Here they were brought before a federal judge, and at the Public hearing Librado was quickly discharged as the judge, U.S. commissioner James R. Grey, found that the “offences complained of were entirely of a political nature”. Manzano was then released in a similar fashion. This incidentally was the only time that PLM exiles in the U.S were afforded any semblance of so called justice. On his release, Librado intended to resume the publication of Regeneracion, but for unknown reasons this was never realised.

Between his release from prison in November 1906 and the middle of 1907 little or nothing is known of Librado’s activities. These times though were especially hard for the PLM. Ricardo and Villarreal were both on the run after the unsuccessful PLM inspired uprising in Mexico during September/October 1906, and throughout the border states of the U.S. the authorities were relentlessly persecuting PLM members and sympathizers alike. Despite these setbacks Ricardo and Villarreal had made their way to Los Angeles where they began the clandestine publication of Revolucion as a successor to Regeneracion, Librado joining them in June 1907.

In August however, their hiding place was discovered by detectives of the Furlong Agency who were directly employed by Diaz, and they were arrested without warrants and handed over to the U.S. police. Although they were held in Los Angeles county jail they still managed to organize another uprising in Mexico which took place in June/July 1908. For this, at the direct request of the Mexican authorities, all three were held incommunicado for some months. Held in jail for almost two years without trial, they were finally extradited to Arizona in May 1909, where they were sentenced to 18 months imprisonment for “violation of the neutrality laws”.

All three comrades served their sentences together, first in the infamous Yuma jail, and later at the newly built jail at Florence. The conditions in both these jails were appalling, as Villarreal later recalled, and for some of the time Librado was sick. 3

He was also kept in solitary confinement for several days, which was spent in an underground cell in total darkness for requesting a change of employment, as the work he had been given aggravated a lung complaint that he no doubt contracted during his time spent in Mexican jails.

Released in August 1910, the three Junta members returned to Los Angeles where they resumed the publication of Regeneracion where, as Librado wrote later, “…our old ideas of liberty and emancipation in favour of the enslaved and exploited Mexican peons were again expounded…” 4

The new Regeneracion though had gone through a profound change on the very eve of the revolution that it and the PLM had more than any other paved the way for, moving its position from radical liberalism to pure anarchism, appearing as a three page Spanish weekly with a fourth page in English. Librado now devoted himself full time to the production of the newspaper, living and working with his fellow editors, Ricardo, Enrique, Anselmo Figueroa and the British anarchist W.C. Owen, who edited the English section, in the house that served as both editorial offices and home.

In June 1911 however, the offices of Regeneracion were raided by the police and Librado, together with Ricardo, Enrique and Figueroa were arrested on the now familiar charge of “violating the neutrality laws”, and sentenced to another term of 18 months imprisonment which was spent in McNeil Island penitentiary While in prison Librado’s companion Conception died after a long illness, leaving their two children, a boy of 15 and a girl of 11, to be brought up by comrades. In a rare example of compassion the Wilson administration granted him temporary parole to attend the funeral but it was found impossible to raise enough money for his travelling expenses.

On their release in January 1914 Librado and his three comrades returned to Los Angeles where they resumed their work on Regeneracion until it was forced to close down at the end of the year owing to serious financial problems. In the middle of 1915, however, Librado, Ricardo and Enrique together with their families and a few other comrades moved to a small farm they had managed to rent at Edendale, then a rural suburb of Los Angeles. Here all the comrades worked communally on the land. Soon they were able to resume the publication of Regeneracion, the printing being undertaken by Librado himself, working single handedly on an old hand press.

In March 1918, Librado was again arrested, together with Ricardo, this time under the newly founded espionage act for publishing a manifesto addressed to the anarchists and workers of the world in which they were advised to prepare themselves and others for the coming social revolution. Even though this manifesto was published in Spanish, Librado was Sentenced to 15 years imprisonment together with a fine of $15,000 and Ricardo to 20 years and a fine of $20,000. “During the Secret trial,” Librado wrote later, “the conspiracy and intrigue was clear. Judge Bledsoe gave his instruction to the jury with a firm and arrogant tone, saying, ‘the activities of these men have been a constant violation of the law, all laws. They have violated both the law of God and the law of Man.” 5

Both Librado and Ricardo were taken again to McNeil Island to serve their sentences, but in December 1919 Ricardo was transferred to Leavenworth Penitentiary, Kansas owing to his failing health. Some nine months later Librado was transferred to the same prison.

While in prison the plight of both Librado and Ricardo were being well publicised within Mexico. Several protest strikes were held, organised by workers groups including the newly formed anarco-syndicalist C.G.T. (Confederacion General de Trabajadores) and U.S. goods were boycotted in an attempt to force the U.S. authorities to free the two men. The U.S. authorities for their part resisted this as much as they could, saying that Librado and Ricardo were dangerous anarchists and therefore could not be released, or that they showed no ‘repentance’ for their alleged crime. Even the Mexican authorities intervened, no doubt forced to through popular will, and instructed its embassy in Washington to intercede with the U.S. government on behalf of Librado and Ricardo. This came to nothing, but in a letter to an embassy official who wanted to know the reason for his imprisonment, Librado explained his anarchist ideas.

“During the struggle for justice in favour of the oppressed I arrived at this conclusion: – governments, all governments, in whatever form they appear, are always on the side of the strong against the weak. Governments have not been created to protect the lives and interests of the poor but for the rich, who constitute a very small minority, while the great masses of the poor form 99% of the earth’s inhabitants. For this reason I am against such a system of injustice and inequality and search for a new society which would have as well as Liberty, Love and Justice for all…” 6

For Librado the rigours and monotony of prison life were added to by the state of Ricardo’s health. Over a period of two years he witnessed the worsening of his old comrade’s condition and his growing blindness, both aggravated by a total denial of adequate medical attention. In early November 1922, Ricardo was transferred from the cell he occupied adjacent to Librado, to another some distance away. On November 20th, Librado saw him for the last time. Of this, he wrote later: “…that afternoon was the last time that Ricardo and myself met and exchanged words, words that will remain with me in my memory as an eternal farewell to the comrade and dear brother with whom I shared 22 years of constant harassment, threats and imprisonment by the hired ruffians of the capitalists. ..” 7

Two days later, Ricardo was found dead in his cell. Although the ‘official’ cause of death was put down to a heart attack, Librado believed he was murdered. He was even more convinced of this when the Prison authorities dictated to him the text of the telegram that he should send to Ricardo’s companion.

In early 1923 Librado was released from Leavenworth and was promptly deported to Mexico. After spending some time in San Luis Potosi where he refused an invitation from the Partido Reformista “Juan Sarabia” to run for congress, he settled in Villa Cecilia, Tamaulipas (today Ciudad Madero). Here he edited Sagitario, a newspaper founded by the anarchist group Los Hermanos Rojos. Sagitario, which had a wide circulation both in Mexico and abroad, was mainly concerned with spreading anarchist propaganda amongst the petroleum workers of the area. This met with great success, and in November 1924, Librado was able to write “With redoubled strength new ideas are flourishing and new groups are being formed. Anarchist propaganda is becoming more and more abundant in the petrol areas…” 8

In the columns of Sagitario he also exposed some of the myths of the so-called ‘socialist’ regime of Calles, including the farce of land redivision and the persecution and murder of the Yaquis Indians and the theft of their land by government officials. It was ostensibly for this last exposure that Librado was arrested in April 1927 together with two co-workers on Sagitario. Taken to Andonegui penitentiary, Tampico, he was held for over 6 months, during which time he both contributed articles to Sagitario and wrote a so-far unpublished autobiographical piece Frente a las Tiranias.

If the authorities thought that by imprisoning Librado they could silence him they were rudely mistaken: “The intention of the tyrants” he wrote from prison, “is to isolate me from contact with the outside world in order to ‘regenerate’ me. I declare that they have failed. Fourteen years of incarceration has so far not succeeded in doing this. Their instrument of torment has always broken into a thousand pieces on the rock of my inviolate will in… which rests my conviction, pure and simple, of human emancipation.” 9

Finally brought to trial, accused of ‘insulting the President’, ‘making a public apology for anarchism’, and ‘inciting the people to anarchy’, Librado conducted his own defence, demanding an unconditional release and substantiating his charge of murder against the Calles administration. Although sentenced to six months imprisonment, he was released after serving only six weeks, most probably on the direct orders of Calles himself, who no doubt thought that Librado presented a bigger threat to him inside prison than outside.

While Librado was in prison the offices of Sagitario were raided by the police and the presses smashed. Shortly after, the authorities suppressed the paper altogether by banning it from the post. On his release therefore Librado moved to Monterey, Nuevo Leon, and after much effort and sacrifice succeeded in resuming publication of the paper under the new title of Avante, but owing to police harassment only three issues were produced.

Enduring much hardship Librado managed to resume publication of Avante in mid-1928, but in February 1929 he was again arrested and the offices and presses of Avante destroyed by the police. Held in Tampico military prison he was immediately subjected to systematic ill treatment including being beaten brutally with a piece of wire cable by General Eulogio Ortiz, who became outraged by the dauntless spirit of the old man. Later the brave General tried to murder Librado, but he was a bad shot and the bullet went wild. The authorities also threatened to inject him with Bacillus to make him ‘confess’ to complicity in the recent assassination of Obregon, but the threat was never carried out. After being held for two months Librado was freed, and he returned to Monterey where the publication of Avante was resumed yet again. Less than a year later the postal authorities banned Avante from the mail as it claimed that it ‘attacked the government of the republic’. Two days later a force of federal soldiers under the command of Ortiz raided the paper’s offices and destroyed all they found, including a complete edition of Regeneracion.

With Avante killed by the authorities Librado moved to Mexico City, where he lived with Nicholas T. Bernal, whom he had known while in the U.S. In 1931, he began publication of Paso and did much to publicise the plight of school teachers in San Luis Potosi whom the government refused to pay.

In February 1932 Librado was involved in an automobile accident. Badly injured he was taken to hospital, where owing to neglect he contracted tetanus, from which he died on March 1st. Even as he lay dying he still possessed the spirit of revolt and resistance that had directed and sustained him throughout his life. As a nurse lifted a sheet to protect his face from the flies he tried to move it away. “Still so rebellious comrade” mocked the nurse, “Always I have fought” Librado replied, “and still I fight against the injustices of the strong”. 10

In a rare tribute to Librado published in the anarchist press, the Scottish anarchist T. H. Bell wrote: “long after the petty tyrants who triumph today have been forgotten, warm youthful hearts in your native land will be inspired by the tale of the steadfast courage and constant devotion of Librado Rivera.” 11

Dave Poole

NOTES

1) Letter from Librado Rivera to Manuel Tellez – June 12th, 1921, in Por la Libertad de Flores Magon y Companeros, Mexico City, 1922, pp 85-95.

2) Quoted in Carlos Slienger, Algunos datos Sobre Librado Rivera, Regeneration March-April 1970.

3) Antonio I. Villarreal, Reminiscences of my Prison Lite, Regeneracion September 10th-17th and 24th, 1910.

4) Letter to Manuel Tellez, op. cit.

5) Librado Rivera, Persecucion y asesinato de Ricardo Flores Magon, in rayos de Luz, Grupo Cultural ‘Ricardo Flores Magon’ Mexico City, 1924.

6) quoted in Slienger op. cit.

7) Rivera op. cit.

8) Quoted in Slienger op. cit

9) Ibid.

10) Interview with Nicholas T. Bernal in James D. Cockcroft, Intellectual Precursors of the Mexican Revolution, University of Texas Press, 1968, p 232.

11) T.H. Bell, Recollection of Librado Rivera, The Road to Freedom, June 1932.

Also

From Behind the Bars, by Librado Rivera (1923)

The Pacification of the Yaqui, by Librado Rivera (1927)

In Memory Of The Unyielding Anarchist Rebel, Librado Rivera, by It’s Going Down (2023)