From ‘Vanguard: A Libertarian Communist Journal‘, June-July 1936, New York City, an extract from a letter written by Emma Goldman in response to a questionnaire sent out by the “Mas Legas” group in Spain

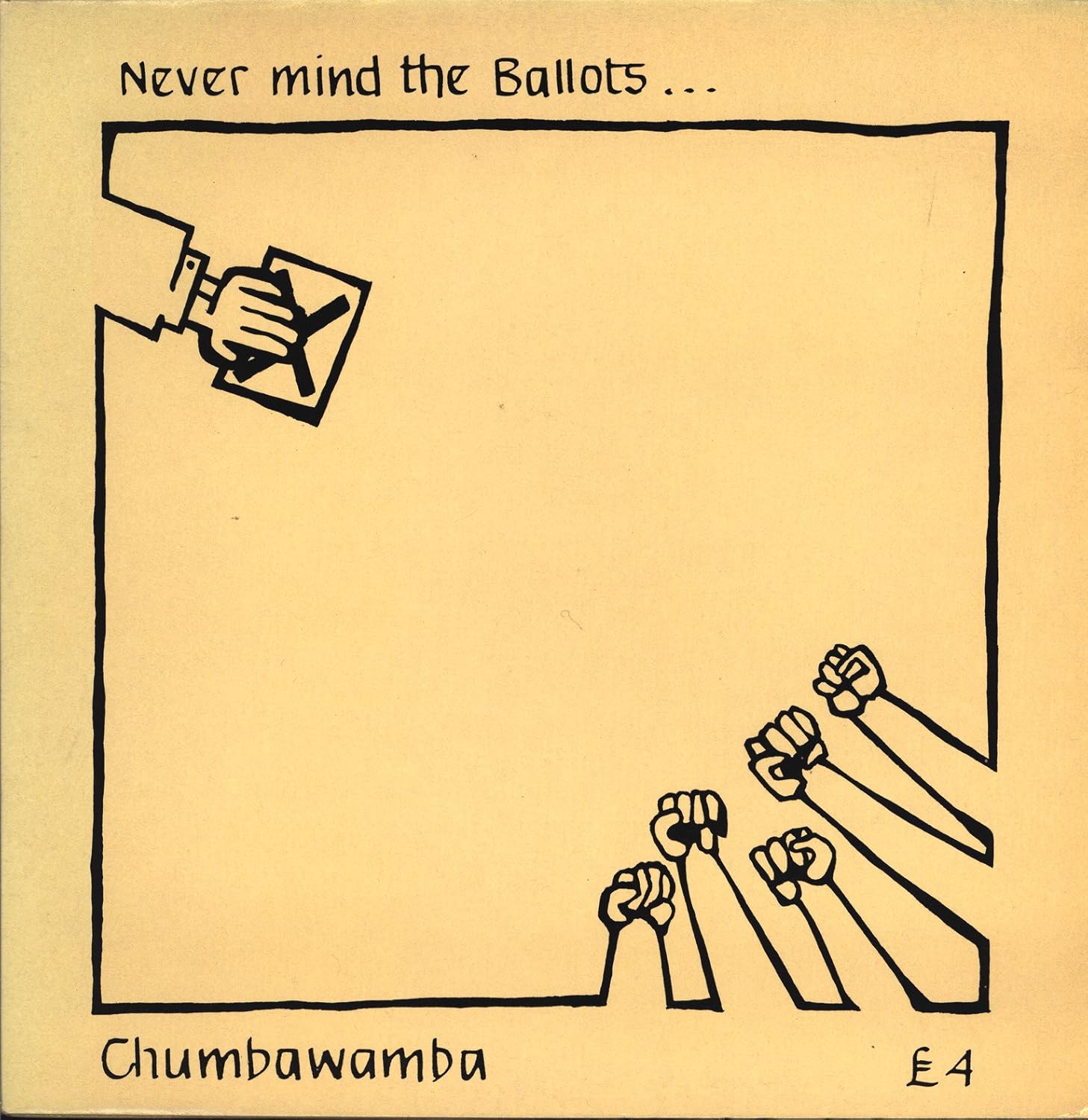

First, the question as to whether the abstention from participation in elections is for Anarchists a matter of principle? I certainly think it is, and should be for all Anarchists. After all, participation in election means the transfer of one’s will and decisions to another, which is contrary to the fundamental principles of Anarchism.

Secondly, since Anarchists do not believe in the Jesuitic formulas of the Bolsheviki that the end justifies the means it is but logical for Anarchists not to consider political participation as a “simple question of tactics.” Such tactics are not only incompatible with Anarchist thought and principles, but they also injure the stand of Anarchism as the one and only truly revolutionary social philosophy.

Thirdly, “can Anarchists, without scruple, and in the face of certain circumstances exercise power during a transition period?” I confess I was surprised to see such a question come from Spain which had always stood out to us in all countries as the high water mark of Anarchist integrity and consistency. Even without the experience of the Russian Revolution and Soviet claims for the transition period I should not have expected the Spanish Anarchists to be carried away by that term in the name of which every crime against the Revolution has been committed by the Communist Party in and outside of Russia. They claim that power is inevitable during the transition period. Unless the comrades in Spain now in favor of the same Jesuitic contention imagine that they are so much wiser and less corruptible than others, I cannot understand how they can possibly aspire to power.

From its very inception Anarchism and its greatest teachers have maintained that it is not the abuse of power which corrupts everybody, the best more often than the worst men; it is the thing itself, namely power which is evil and which takes the very spirit and revolutionary fighting strength out of everybody who wields power.

There is ample excuse for Marxians since they believe in and propagate the state, they believe in and propagate power, but how can the Anarchists whose social philosophy repudiates the state, all political power all government authority, in short, every sort of power and authority over fellow man? To me it is a denial of Anarchism and a most dangerous tendency which if carried out is likely to undermine whatever advance and recognition as a revolutionary fighting force the Anarchists in Spain represented for so long.

Does this mean that I do not recognize the danger of Fascism, or do not appreciate the imperative necessity to fight it to the last degree? Nothing is farther away from my thoughts. What I do mean to say is this: if the Anarchists were strong and numerous enough to swing the elections to the Left, they must have also been strong enough to rally the workers to a general strike, or even a series of strikes all over Spain.

Now, the psychological moment for all Anarchists in Spain to use their economic and direct action was during the revolt of October 1934. It was their bounden duty to join the workers and fight with them to the end. The excuse given at the time by the C.N.T. [National Confederation of Labour in Spain] for leaving the heroic masses in the Asturias to their fate was that it did not want to affiliate itself with the Socialists, with men like Caballero who had so often stabbed our comrades in the back. It was a poor excuse. But granted, for arguments sake, such an attitude was justified. How then could some of the Anarchists join the Socialists in elections?

The comrades were actuated in their participation in the elections by their solidarity with the 30,000 political prisoners. That was undoubtedly a very commendable feeling. But at the same time their amnesty was merely a short breathing spell. For it is al ready apparent that the new rulers in the saddle will not leave the prisons empty for very long.

In conclusion let me say, that though some of the Anarchists in Spain may be dazzled by the success of the Communists in different countries it is yet true that they are but of the hour. The future belongs to those who continue daringly, consistently to fight power and government authority. The future belongs to us and to our social philosophy. For it is the only social ideal that teaches independent thinking and direct participation of the workers in their economic struggle. Nor it is only through the organized economic strength of the masses that they can and will do away with the Capitalist system, and all the wrongs and injustice it contains. Any diversion from this stand will only retard our movement and make of it a stepping stone for political climbers.

Also on electoral politics

Abstention, by Alfredo M. Bonanno (1985)

What Are We Voting For?, by Marie Louise Berneri (1942)

The Woman Suffrage Chameleon, by Emma Goldman (1917)

Why Anarchists Don’t Vote, by Elisée Reclus (1913)

The Political Socialists, by Ricardo Flores Magón (1912)

Woman Suffrage, by Emma Goldman (1910)

The IWW and Political Parties, by Vincent St. John (1910)

The Ballot Humbug, by Lucy E. Parsons (1905)

Lucy E. Parsons’ Speeches at the Founding Convention of the Industrial Workers of the World (1905)

The Socialists and the Elections, by Errico Malatesta (1897)

The State: Its Historic Role, by Peter Kropotkin (1896)

On Voting, by Elisée Reclus (1885)