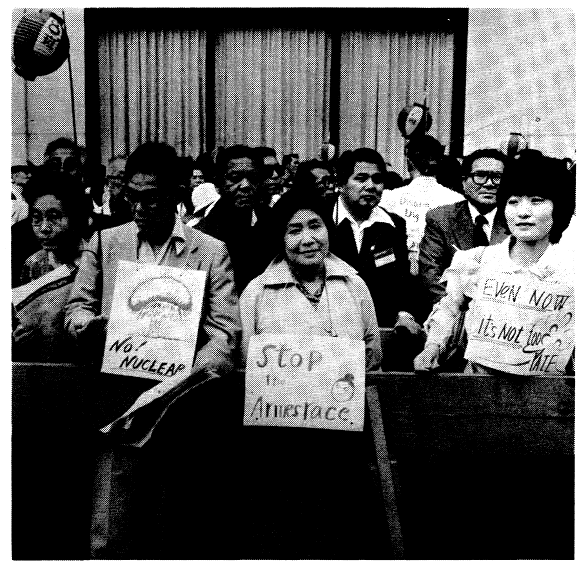

Japanese delegation outside United Nations, May 27, 1978 (credit: Stan Sierakowski / LNS)

From ‘Liberation News Service’, May 19, 1978, New York City

LAGUNA, N.M. (LNS) — A delegation of 22 Japanese anti-nuclear activists and Hiroshima survivors recently visited New Mexico, the birthplace of the atom bomb. The early May visit was part of their month-long tour of the various stages of the U.S. nuclear fuel cycle and part of an effort to support the U.S. anti-nuclear movement.

The three-day visit to New Mexico included a stop at Los Alamos Laboratories, a briefing on the planned national nuclear waste site near Carlsbad, N.M., meetings with environmental and anti-nuclear groups, and a tour of the Grants Uranium Belt guided by local Indian leaders.

The Japanese group attended the national anti-nuclear demonstration outside the Rocky Flats, Colorado plutonium weapons plant April 29. Several members of the group also traveled to Barnwell, South Carolina for a demonstration against a nuclear reprocessing plant there, the group also carried their message of protest to United Nations Ambassador Andrew Young.

Japanese Movement

The delegation includes a 62-year-old and a 70-year-old survivor of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Other members of the delegation are children of survivors who carry the genetic imprint of the bomb’s radiation poisoning.

“These people are known in Japan as hibakasha [or “hibakusha”] — meaning one who is exposed to radiation,” explained Judy Hurley, national coordinator of the tour. “In the past hibakasha was used only in reference to those who lived through the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But the anti-nuclear delegation believes the word should be used also to describe people exposed to radiation from nuclear power plants as well as the worldwide victims of radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing,” said Hurley, who also works with the Mobilization for Survival in Boulder.

“The Japanese government is almost deaf to nuclear protest,” explained delegation member Nagahisa Wada. “We have 15 nuclear power plants operating in Japan. Those reactors are having accidents all the time, exposing the workers to radiation. Low level radiation from the power plants is causing cancer in workers.”

“The government doesn’t listen to the people. They would like to use nuclear power as an incentive for the national economy despite the big movement against it.”

The Japanese delegation appropriately began their New Mexico tour at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratories, where “Fat Man” and “Little Boy,” the bombs that fell on the Japanese cities, were engineered. They presented a lab official with a bottle melted by heat half a mile away from the center of the Hiroshima blast. They demanded that all nuclear weapons research and testing immediately stop.

Meet With Indian Uranium Miners

The anti-nuclear group then traveled to the uranium belt in northwestern New Mexico, where over one half of U.S. uranium reserves lie. Guided by Indian representatives from the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC), they saw the largest open pit uranium mine in the world, the Jackpile mine on the Laguna reservation, where Native American miners are on strike for a new contract. (They are demanding from Anaconda Copper wages and benefits on a par with the other uranium companies in the area. The miners claim that they are being discriminated against because they are Indian.)

The Japanese visitors joined the strikers’ picket line and sang Japanese union songs. Masafumi Takubo, a spokesperson for the group, said that their trip was being financed by Japanese labor unions.

The following day the group headed north to the town of Shiprock on the Navajo Indian Reservation where they met with widows of Navajo uranium miners who died of cancer from working in the Kerr McGee uranium mine on the reservation. They also toured the abandoned site of an old uranium mill which had left radioactive tailings scattered throughout the property. Engineers from the Navajo tribe are now trying to decontaminate the area.

Takubo noted the threat of “physical and cultural deterioration of the Indian people” in New Mexico and compared their plight to that of Australian aborigines currently protesting uranium mining on their traditional lands. “In Australia, they say that their land is an egg which if broken into will destroy the whole world. Because of the radioactivity fallout and contamination from nuclear weapons and power plants, there is much truth in that,” said Takubo, who works with a citizens’ anti-pollution group in Tokyo.

Takubo explained that “the people protesting [in Japan] are mainly fishermen, farmers and residents of the polluted areas,” and observed, in contrast, that in the United States, many of the environmental activists are middle-class people not directly affected by major pollution problems. In Japan, there is a large anti-nuclear weapons movement, but less knowledge and activity focusing on the hazards of nuclear power plants.

After visiting New Mexico, the Japanese delegation moved on to the Palo Verde Nuclear Power Plant in construction near Phoenix, Arizona, the Nevada nuclear weapons test site of Las Vega, and the Westinghouse headquarters in San Francisco. A small delegation also planned to visit the Trojan Decommissioning Alliance in Oregon and attend a mass rally at the Trident nuclear submarine base in Bangor, Washington near the end of May.

Korean A-Bomb Victims Visit U.S.; Protest Discrimination by Japan, S. Korea Nuclear Threat – Liberation News Service (1978)

From ‘Liberation News Service’, June 2, 1978, New York City

NEW YORK (LNS) — Two Korean residents of Japan traveled to New York City in late May to publicize the status of Korean A-bomb victims of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear blasts. Speaking in Japanese, Park Chang Gi and Ri Sil Gun of the Korean A-Bomb Survivors detailed the severe medical and economic discrimination leveled at the “Japanese Koreans.”

They addressed the New York City press conference while a large delegation of Japanese participated in the United Nations Disarmament Session. They explained that five thousand Koreans in Japan are victims of the nuclear blasts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Many more Koreans, however, in North and South Korea, were also in Japan at the time of the hibakusha, or the radiation blasts. Thirty thousand Koreans died immediately.

In spite of the large Korean population directly affected by the nuclear attacks, the Japanese government covers medical needs of Japanese victims but accepts no responsibility for the Koreans’ medical claims. Korean victims residing in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK–North Korea) fare better since the government provides free medical attention. The medical problems of all victims include sterility, stomach and liver cancers, grotesque keloid formations on the skin and genetically deformed children.

The Japanese government did formulate a Catch 22-type provision for Korean A-Bomb survivors: Koreans can claim reparations if they can find two Japanese citizens who witnessed the attack. Because of the low status the Japanese government attaches to Korean people, few Japanese are willing to act as witnesses. Further, it is extremely difficult to find any Japanese citizen who can recall specifically which person was affected by the blast. Only a handful of Koreans have been able to establish this legal proof.

Remnants of Japanese Colonialism

Many “Japanese Koreans” trace their entry into Japan as far back as 1910 when imperial Japan annexed Korea. Still more, a startling 2,400,000 were conscripted into the Japanese army, munitions factories, mining concerns and road crews during World War II.

And after 1945, explained Ri Sil Gun, executive director of the Hiroshima Korean A-Bomb Survivors, the Koreans were still “treated like cows and horses. We were not only victims of the A-Bomb, but also of Japanese imperialism.”

Discrimination against the 630,000 Koreans living in Japan (total population 110 million) has been institutionalized: Koreans are refused all government jobs and many educational benefits; use of the Korean language and Korean surnames are banned and anyone heard speaking Korean is officially reprimanded; no Japanese secondary schools and only a few universities offer Korean language study.

Koreans are not allowed to travel abroad. The two representatives of the Korean A-Bomb Survivors who spoke at the May 26 press conference brought the total of “Japanese Koreans” ever admitted to the United States to four. As it is, they are banned from observing the U.N. Disarmament Session proceedings during their visit.

U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Korea

The Koreans’ efforts to speak out against such odds are a reminder of the focus of nuclear threat in the world to- day. For at present, more than 680 nuclear weapons are housed in silos and underground tunnels in South Korea — direct sales from the U.S. government.

The Park government has been conducting nuclear research and constructing nuclear reactors during the past two years. The DPRK has consistently stated that it has no money, space or inclination to produce nuclear weapons.

All of the weapons in South Korea put together are an incomprehensible 400 million times more potent than the bombs dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Those bombs alone destroyed 95 percent of the two cities with a destructive force of 10,000 tons of TNT.

Also

Strange Victories, by Midnight Notes / Elephant Editions (1979/1985)

How We See It, by the Vancouver Five (1983)

Against Nuclear Technology, by Pierleone Porcu (1986)

For The Navajo Nation, Uranium Mining’s Deadly Legacy Lingers, by Laurel Morales (2016)

The Irradiated International, by Lou Cornum (2018)

Indigenous labour struggles, by M.Gouldhawke (2022)