Part 7 of “Northwest Coast Indigenous Resistance to Colonization” by Zig-Zag

(See Warrior Publications for more documents and articles by Zig-Zag. A roughly scanned PDF of the full document from which this excerpted part was taken can also be found here at the website of Grassroots Women)

7. BIOLOGICAL WARFARE: DISEASE AND DEPOPULATION

The deadly effects of European-introduced diseases are generally acknowledged in colonial history. Disease epidemics are in fact commonly associated with the European invasion of the Americas, beginning with the Spanish conquistadors. They are included in history because of their great impact on Indigenous populations (which cannot be denied) and because they provide an easy answer to the question: What happened to all the Indians?

Although European diseases were the primary cause of depopulation, these occurred most often under conditions of genocidal war involving massacres, scorched earth policies, forced relocation, starvation, etc. Under such conditions, there is little doubt that European military commanders welcomed the effects of disease on hostile Indigenous populations. Nor would they have been ignorant to the concept of biological warfare itself.

BACKGROUND & HISTORY OF BIOLOGICAL WARFARE

At least as far back as the 14th century, the use of biological warfare had been introduced to Europe. At that time, the Tartars laid siege to the walled city of Kaffa along the Black Sea. A bubonic plague outbreak occurred among the invaders. They used catapults to fling corpses of plague victims over the walls. An epidemic then occurred within the city. Those who escaped returned to Italy, where they spread the disease into Europe. This resulted in the Black Death, in which millions eventually died.

If you find it difficult to conceive of military commanders resorting to biological warfare, then recall how Europeans felt about Indigenous peoples. To many, our ancestors were non-Christian “heathens & infidels,” savages, cannibals, subhumans lacking in souls. They were more like animals, and it was the duty of Christians (white Europeans, that is) to take their land, enslave them, and even exterminate them.

This was the official response of the church to Columbus’ 1492 “discovery” of the Americas, which provided legal and moral sanction to genocide. By the 1700’s, this attitude had not changed. Colonial settlers were still engaged in a life and death struggle with Indigenous peoples, who were still seen as an inferior race of dirty savages. The call to exterminate the Indians was widespread throughout colonial North America.

Sir Jeffrey Amherst was a British military commander who fought many battles against the French and their Indigenous allies. While he saw the French as ‘worthy enemies’, he hated the Indigenous people. Today, he provides the best documented cases of the use of biological warfare in North America against Indigenous peoples.

According to the US Center for Disease Control (CDC):

“Before the discovery of the smallpox vaccine, smallpox was in fact used as a weapon. One of the best documented examples of this occurred during the French & Indian War. The British had been defeated in their attempt to conquer Fort Carrillon on Lake Champlain. So Sir Jeffrey Amherst, commander of the British forces, met with Indians who were sympathetic to the French. Under the pretense of friendship, he deliberately offered them blankets previously used by smallpox victims. The Indians, who lacked immunity to smallpox, suffered a devastating outbreak of the disease. The English were then able to successfully attack the fort…”

Joanne Cono, MD, Centres for Disease Control & Prevention (in the CDC video The History of Bioterrorism, 1999).

Fort Carillon was taken by the British in 1759. A far better documented use of biological warfare occurred in 1763, during Pontiac’s rebellion. At this time, the French had been defeated and Amherst was commander-in-chief of all British forces in N. America. An Indigenous insurgency had captured several forts, and Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh) was under siege:

“…Captain Simeon Ecuyer had bought time by sending smallpox-infected blankets and handkerchiefs to the fort – an early example of biological warfare – which started an epidemic among them. Indians surrounding Amherst himself had encouraged this tactic in a letter to Ecuyer.”

(Atlas of the North American Indian, p. 108)

In a letter reportedly written by Amherst himself, he appeals to Colonel Henry Bouquet:

“Could it not be contrived to send the small pox among those disaffected tribes of Indians? We must on occasion use every stratagem in our power to reduce them.”

(quoted in The Conspiracy of Pontiac and the Indian War, p. 39)

Shortly after, a smallpox epidemic broke out among the Delawares and the insurgency was eventually defeated. Amherst is the most well-documented example of bio-warfare, but some scholars assert that it was far more common:

“Our preoccupation with Amherst has kept us from recognizing that accusations of what we now call biological warfare – the military use of smallpox in particular – arose frequently in 18th century America. Native Americans, moreover, were not the only accusers. Seen in this light, the Amherst affair becomes not so much an aberration (an unusual exception] as part of a larger continuum in which accusations and discussions of biological warfare were common, and actual incidents may have occurred more frequently than scholars have previously acknowledged.”

(Elizabeth A. Fenn, “Biological warfare in 18th century N. America”, Journal of American History vol. 86, no. 4, March 2000, p. 1553)

Another incident in which it is believed that the British used biological warfare was during the American Revolutionary War. During the winter of 1775-76, American forces were attempting to take Quebec from British control. They captured Montreal. But in December 1775, the British fort commander reportedly infected the Americans, causing massive casualties. The American forces retreated after burying their dead in mass graves.

“[Historical events and records] suggest that the use of smallpox as a weapon may have been widely entertained by British military commanders, and may have been employed without scruple when opportunity offered possibly on a number of occasions”

(Wheelis, “Biological warfare before 1914,” Biological and Toxin Weapons, p. 29).

A smallpox vaccine was developed in 1796, and it was nearly eradicated around the world by 1980. As a result, vaccination has not been continued. Due to concerns of bio-terrorism, however, the US has stockpiled smallpox vaccines, and it is still listed as a category A disease by the CDC. This list also includes anthrax, botulism, and the plague. The CDC website states “If these germs [type A] were used to intentionally infect people, they would cause the most illness and death.” This tells us that smallpox is a highly contagious & deadly disease.

IMPACT OF DISEASE ON NORTHWEST COAST

The earliest epidemics on the Northwest Coast are believed to have occurred in the early 1770’s and to have caused large numbers of deaths. This time period coincided with the arrival of the first Spanish ships (1774), although scholars believe the epidemic was spread through intertribal trade to the south. Whatever the case, disease epidemics were still having a devastating effect in the 1780’s and 90’s.

The 1788 journal of James Colnett refers to Kildidt Sound and describes an empty village and many corpses. Likewise, Capt. Vancouver noted seeing hundreds of dead at one village, in 1792.

Epidemics would continue throughout the coast into the 1880’s, and included smallpox, measles, influenza, syphilis, and others. Within a century of contact (1774-1874), the Indigenous population on the Northwest Coast is estimated to have declined by a minimum of 80% (from 200,000 to 35,000).

SMALLPOX

Smallpox caused the greatest number of deaths on the Northwest Coast. Boyd identifies three major smallpox epidemics; one in the 1770’s, one in 1836, and another in 1862, with mortalities ranging from one-third to two-thirds of the population (Spirit of Pestilence, p. 204). Recall that smallpox is classified as a type A biological weapon by the US Centre for Disease Control.

Smallpox is a highly infectious disease in which the victim suffers high fevers, aches, rashes, and small raised bumps over the skin. Transmission is through prolonged face-to-face contact, and direct contact with infected bodily fluids or contaminated objects such as bedding or clothing.

The first symptoms are red spots on the tongue and inside the mouth. These turn into sores that break and spread large amounts of the virus into the mouth and throat. The victims gets a rash on the skin, which starts in the face. This rash turns into small bumps, which become hard and then scab.

For Indigenous peoples with no immunity, smallpox was a terrifying and painful form of death, on a scale never seen before. In 1796, a vaccination for smallpox was first developed by Dr. Edward Jenner in England. As early as 1802, US Army doctors began vaccination of Indigenous camps located around Army forts in an effort to stop epidemics. The first large scale smallpox vaccination of Indigenous people was authorized by the US Congress in 1832.

1862 SMALLPOX EPIDEMIC

The worst smallpox epidemic on the Northwest Coast occurred in 1862, following the discovery of gold in the Fraser Canyon in 1858. After this, thousands of settlers began to arrive. Fort Victoria grew from a couple hundred to several thousand. Indigenous people would also gather around the fort, where different nations soon had camps set up to trade.

In late March, 1862, the first case of smallpox infection was reported in a local Victoria newspaper. It is believed to have been introduced by a prospector who arrived from San Francisco. As infections increased, authorities initially began inoculation shots. Several hundred Indigenous people were in fact immunized with smallpox vaccine.

Within a month of the outbreak, however, the northern tribes were given one day to leave and threatened with gunboats (April 28, 1862). On May 11, the HMS Grappler and Forward escorted 26 canoes out of the harbor. Two days later, police destroyed all lodges at the camps of northern tribes, leaving hundreds without shelter:

“Alarmed, the authorities burned the camps and forced the Indians to leave. They started up the coast for home, taking the disease with them, leaving the infection at every place they touched. The epidemic spread like a forest fire up the coast and into the interior” (The Indian History of BC, p. 59)

David Walker, a naval surgeon stationed on the coast at this time, commented on government policies in regards to disease, stating:

“If it were intended to exterminate the natives of this coast no means could be devised more certain than that of permitting these miserable wretches to return home in a state of sickness and disease; wives, husbands and children become contaminated, and that too in places beyond medical aid, unchecked in its ravages this disease cuts off the prime of the population, and leaves the remainder physically unsuited to continue the habits and pursuits of their forefathers”

(quoted in Gunboat Frontier, p. 80-81)

And yet, colonial authorities not only “permitted” infected persons to return to their villages, they forced them to, knowing full well the devastating effects of European disease. Commenting on the 1862 smallpox epidemic, Boyd states:

“…this epidemic might have been avoided, and the whites knew it. Vaccine was available. and the efficacy of quarantine was understood.”

(Spirit of Pestilence, p. 172)

At this time, the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia were beginning their expansion of settlements. Fertile land was being identified and taken for farming, in order to feed this growing population. All types of business opportunities were being encouraged: logging, sawmills, fishing, canneries, mines, stores, schools, building construction, etc.

The Hudson’s Bay Company, which retained control of the colonies until 1859, had been instructed to sell land and to use part of this profit to improve infrastructure (i.e., roads, bridges). In 1854, the HBC published a pamphlet in England entitled “Colonization of Vancouver’s Island” to raise awareness of the colony. Ads were also placed in English newspapers to attract settlers.

Settlement was greatly stimulated by the 1858 gold rush in the Fraser Valley and southern interior, which brought as many as 30,000 prospectors from the US in the first 2-3 years. The gold rush was big news, and the lure of quick & easy money was widely promoted. Most ‘prospectors’ arrived at Fort Victoria. A huge service industry emerged just to feed, transport, house and re-supply these trails and camps. Prostitution and whiskey also flourished in the ‘boom towns’.

The establishment of the colony of British Columbia (the mainland) in 1858 – the year of the gold rush – was necessary for the government to keep control of the area, and to limit any American influence across the border.

Nevertheless, the problem of every colonial occupation & settlement is what to do with the Indigenous people. Throughout the 1850’s, the HBC government had had to contend with an ongoing Indigenous insurgency. Despite the bombings of villages, raids, and public executions of chiefs & warriors, attacks had continued. Settlers were still being killed, and ships were still being destroyed on the coast.

These activities created the first period of ‘economic uncertainty’, and for this reason the government sought to quickly & immediately pacify the Indigenous population. As noted previously, the government devoted great resources to punishing any Indigenous resistance that resulted in deaths or injuries to settlers. It had to show that it could impose control over Indigenous people, thereby protecting the lives & property of settlers.

For colonial authorities & businessmen, the smallpox epidemic of 1862 could not have occurred at a more ideal time. It dampened Indigenous resistance throughout the region and drastically reduced the population, just as settlement was officially promoted. Some estimate that 20,000 died within 1 year of the initial outbreak at Fort Victoria.

As noted, authorities knew the proper procedures for dealing with smallpox epidemics (inc. vaccination & quarantine); a vaccine had been developed in 1796, and even the US Army vaccinated Indigenous people gathered around its forts. The precedent for biological warfare using smallpox had already been set by Amherst, in 1763. Amherst, recall, was the commander of all British military forces in N. America.

Colonial authorities at Ft. Victoria could not have been ignorant to the consequences of their actions, which actively promoted the spread of smallpox throughout the entire coastal region, causing tens of thousands of deaths.

MEASLES, INFLUENZA, TUBERCULOSIS, AND SYPHILIS

Other diseases which also caused extensive deaths were measles, influenza, tuberculosis, and syphilis.

Measles is an infectious disease in which the victim suffers high fevers and red spots on the skin. In 1868, a measles epidemic spread through the Heiltsuk, Haisla, Tsimshian, and Tlingit.

Influenza is the flu, a respiratory disease which causes fevers, aching cramps, arid coughs. Some strains of influenza are deadly; after World War 1 a global flu epidemic killed some 25 million people, more than those killed during the entire war. For Indigenous people, influenza was also deadly.

Tuberculosis is another respiratory disease. In the early 1900’s, tuberculosis epidemics were a major cause of death among Indigenous peoples. This has been attributed to,

“Confinement in reserves & overcrowded European-style housing of the lowest quality [which] provided fertile ground with malnutrition, lack of sanitation, despair, alcoholism… from which the infection ran its mortal course through communities.

“The impact of tuberculosis, statistically expressed, was out of all proportion to the size of the Aboriginal population. A study by [DIA medical inspector, Dr.] Bryce revealed that the rate of tubercular infection for Indians was one in seven and the death rates in several large bands 81.8, 81.2, and in a third 86.1 per thousand. The ordinary death rate for. the city of Hamilton was 10.6 in 1921.”

(A National Crime, pp. 83-84)

After contact with Cook’s 1778 expedition, syphilis was most likely introduced by sailors who had sex with prostituted female slaves, provided by the Nu-chah-nulth. Syphilis is a sexually-transmitted disease (STD) that can lead to heart & brain damage, birth defects & still-born babies. In the European middle-ages, syphilis killed millions of people. In the early 20th century, antibiotics were developed to treat syphilis.

In 1997, Vancouver saw a rapid growth in syphilis infection, especially among prostitutes in the Downtown Eastside. By 2003, news headlines proclaimed Vancouver as home to one of the “world’s largest outbreaks of syphilis.

Today, Indigenous peoples in general have much higher rates of infection for diseases such as hepatitis, tuberculosis, HIV AIDS, diabetes, and cancer. Some of these diseases are infectious (hepatitis, AIDS, and tuberculosis) but all of them result from the inferior living conditions experienced by today’s generations of Indigenous people. These conditions are the direct result of colonization & genocide.

IMPACT OF GENOCIDE

From an original population of some 200,000 in 1770, a century later Indigenous peoples would number some 40,000. Within a span of 2-3 years, some 20,000 had also just died (1862 smallpox epidemic). Entire villages disappeared as survivors grouped together (i.e., among the Haida, the villages of Masset and Skidegate became centers of survival). Family lineages, upon which all social organization was based, fragmented and broke apart.

Under these conditions, Indigenous nations began to suffer from a total social breakdown. Vast amounts of Indigenous culture was lost at this time, including history, philosophy, and organization. Many survivors, suffering from trauma and dislocation, abandoned their culture and sought salvation in European ways of life.

Missionaries found fertile ground for their message of Christianity, and they worked constantly to gain converts to their ‘flocks. They built churches & schools, translated hymns & bible stories into Indigenous languages, and even established their own Christian model towns (i.e., Metlakatla). At the same time, alcohol and prostitution flourished, adding to the breakdown of Indigenous society.

By this point, the military strength of the Northwest Coast Indigenous nations was completely broken, and many had already resigned themselves to reservation life and assimilation.

One historian described the effects of disease epidemics on the Yup’ik, a group of Inuit in western Alaska:

“Compared to the span of life of a culture, the Great Death was instantaneous. The Yup’ik world was turned upside down, literally overnight. Out of the suffering, confusion, desperation, heartbreak and trauma was born a generation of Yup’ik people. They were born into shock. They woke to a world in shambles, many of their people and their beliefs strewn around them, dead. In their minds they had been overcome by evil. Their medicines and their medicine men and women had proven useless. Everything they had believed in had failed. Their ancient world had collapsed.

“The survivors taught almost nothing about the old culture to their children. It was as if they were ashamed of it, and this shame they passed on to their children. The survivors also gave up all governing power of the villages to the missionaries and school teachers, whoever was most aggressive. There was no one to contest them. In some villages the priest had displaced the angalkuq. In some villages there was theocracy under the benevolent dictatorship of a missionary, The old [shamans), on the other hand, had fallen into disgrace. They had become a source of shame to the village, not only because their medicine had failed, but also because the missionaries now openly accused them of being agents of the devil himself and of having led their people into disaster.”

(Yuuyaraq: the Way of the Human Being, pp. 11-14)

These first generations of ‘modern’ Indigenous people had different responses to colonialism, differences which still exist to this day. Some embraced assimilation, becoming hardcore Christians and businessmen. Many were also devoted to the British Crown and royal family. Their response to genocide (a survival reflex) was to become model Christians and loyal subjects of the empire.

This describes a great number of our elders; our grandparents and great-grandparents. This is why they had ornaments, paintings, decorated plates, etc., emblazoned with portraits of British Kings & Queens. This is also why so many Indigenous men volunteered for military service in World Wars 1 and 2.

Those who kept their culture and traditional views were impoverished and marginalized by the ‘modernized’ Indians placed in control. They were also subject to punishment after the 1884 Indian Act amendment that banned the potlatch and other ceremonies (i.e., the plains sundance).

Source:

Northwest Coast Indigenous Resistance to Colonization by Zig-Zag (scanned PDF)

Note:

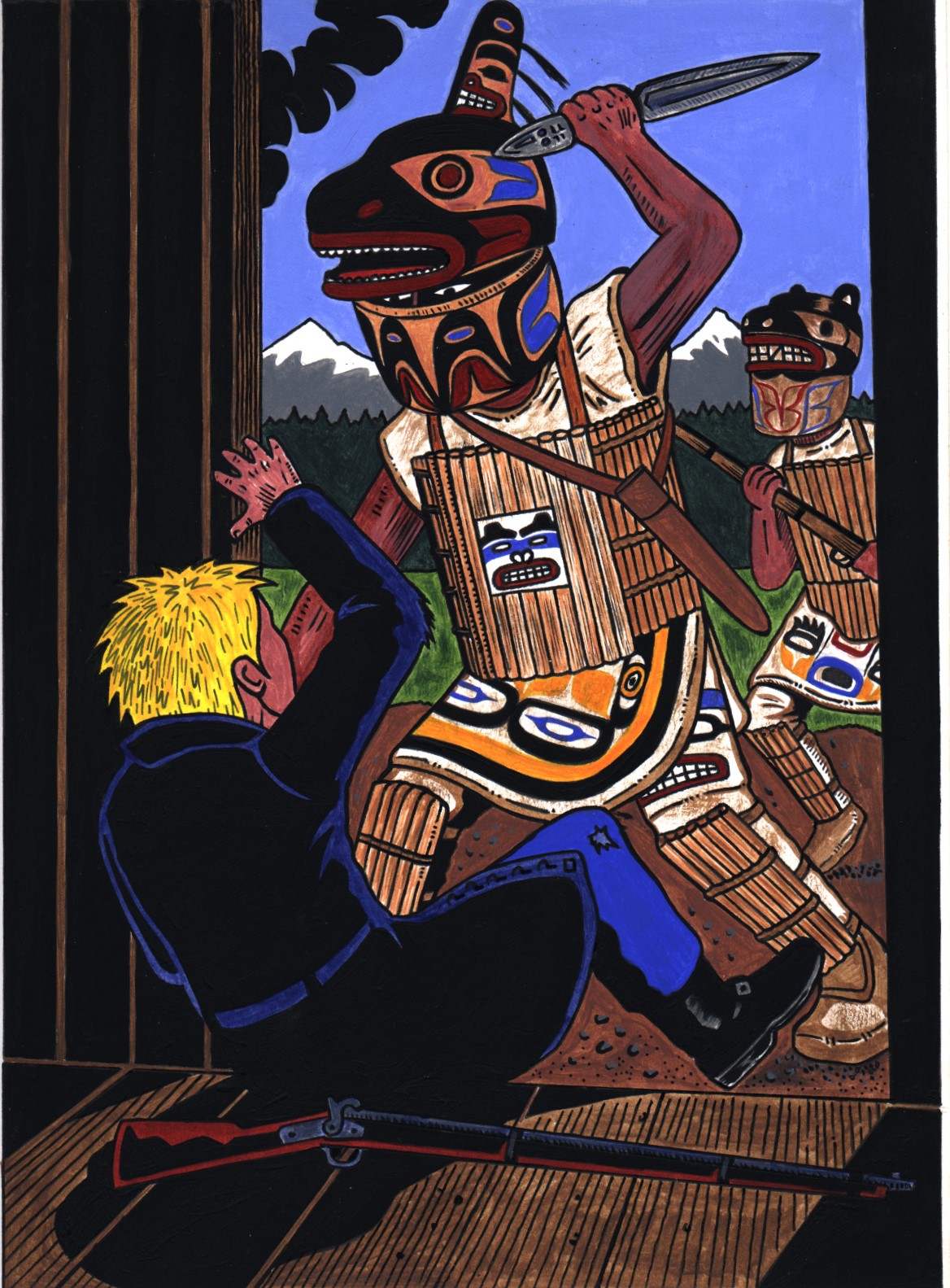

The book cover images I’ve added to this post did not appear in the original print document by Zig-Zag. The artwork by Zig-Zag at the top of this post appears on the cover of the print document.

Related info:

A Smallpox Epidemic & Colonial Quarantine around Lake Winnipeg (1876-1877)

One reply on “Biological Warfare: Disease and Depopulation – Zig-Zag (2004)”

Thanks