Proclamation

NOTICE TO ALL CONCERNED

THAT THIS PROPERTY OWNED BY THE SOVEREIGN PUYALLUP TRIBE AND BEING A PART OF THE PUYALLUP INDIAN RESERVATION,

Known by Native Americans as the Cushman Hospital, and by the State of Washington as Cascadia Juvenile Diagnostic Center,

IS HEREBY TAKEN INTO THE POSSESSION OF THE PUYALLUP TRIBE OF INDIANS AS ITS SOVEREIGN AND RIGHTFUL OWNERS.

PUYALLUP TRIBAL COUNCIL

RESOLUTION NO. 76-10-23

WHEREAS the Puyallup Tribal Council is the governing body of the Puyallup Tribe in accordance with the authority of its Constitution and By-Laws, as amended, approved by the Assistant Secretary of the Interior on the 1st day June, 1970; and

WHEREAS in 1939 the sovereign Puyallup Tribe transferred the land known as the Cushman Indian Hospital and its grounds to the United States Government for the sole and express purpose of building a new Indian Hospital, which would always be an Indian Hospital fulfilling the obligation of the United States of America, under the Treaty of Medicine Creek, to provide Health Care to our People; and

WHEREAS the promises to always use this land as an Indian Hospital made by the United States through its BIA agents and duly and officially recorded by those agents, was also reaffirmed and expressed in the federal legislation that enabled the United States purchase of our land to build a new hospital; and

WHEREAS the United States broke its promises and contract obligations to the Puyallup Tribe when it closed the Cushman Indian Hospital in 1959, which the Puyallup Tribal Council believes and recognizes, as effectively and legally reverting this land to Tribal ownership; and

WHEREAS the United States was in possession of land stolen from the Puyallup Tribe when it refused to stop the Hospital’s closure and then did not give the land back to the Puyallup Tribe; and

WHEREAS the United States, when it transferred the Cushman land and facility to the State of Washington in 1961, transferring by quit-claim deed, could transfer no right in title to the property since it then had none; and

WHEREAS the Puyallup Tribal Council has tried, for the past five years, to arrange peacefully and smoothly for the transfer of possession of Cushman back to the Puyallup Tribe, making requests to the State, the U.S. Congress, and the executive branch through its responsible agencies, with no success and meeting constantly with advice that we should be trying in another way to get our land back; therefore

BE IT KNOWN BY ALL PERSONS, BY THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT AND BY THE STATE OF WASHINGTON That the PUYALLUP TRIBAL COUNCIL, being unable to succeed through these other routes of action, HEREBY RESORTS TO SELF-DETERMINATION AND EXERCISES ITS SOVEREIGN RIGHTS OF OWNERSHIP BY TAKING BACK INTO TRIBAL POSSESSION The Property and facility known as CUSHMAN INDIAN HOSPITAL and known by the State as CASCADIA JUVENILE DIAGNOSTIC CENTER; and further

BE IT KNOWN by the State of Washington that any protest of Tribal POSSESSION of the Cushman (Cascadia) lands and facility may be made to the Puyallup Tribal Council, at the Cushman Hospital, and that such protests will be carefully and duly considered.

CERTIFICATION

I hereby certify that the above resolution was duly enacted at a meeting of the Puyallup Tribal Council held at Tacoma, Washington on the 22nd day of October, 1976, a quorum being present, with a vote of 3 for and 0 against and 2 abstaining.

SUZETTE MILLS, ACTING SECRETARY OF THE PUYALLUP

TRIBE OF INDIANS

ATTEST:

RAMONA BENNETT, CHAIRWOMAN OF THE PUYALLUP

TRIBE OF INDIANS

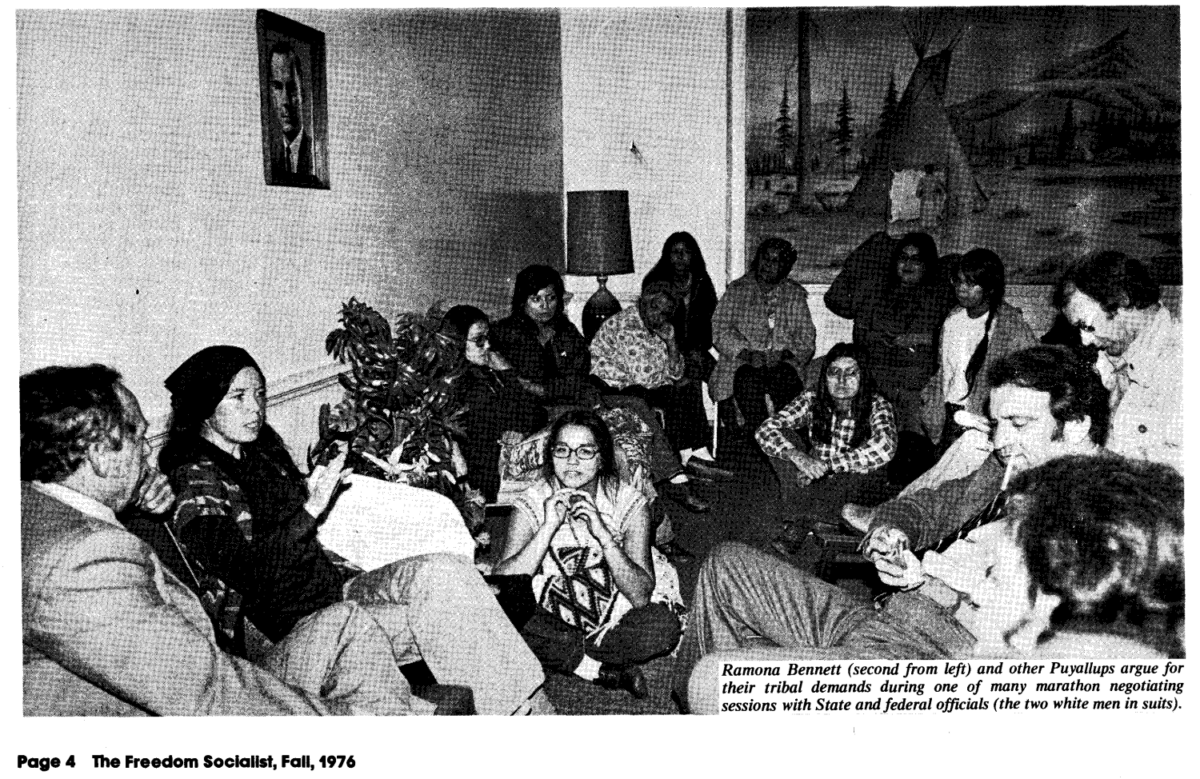

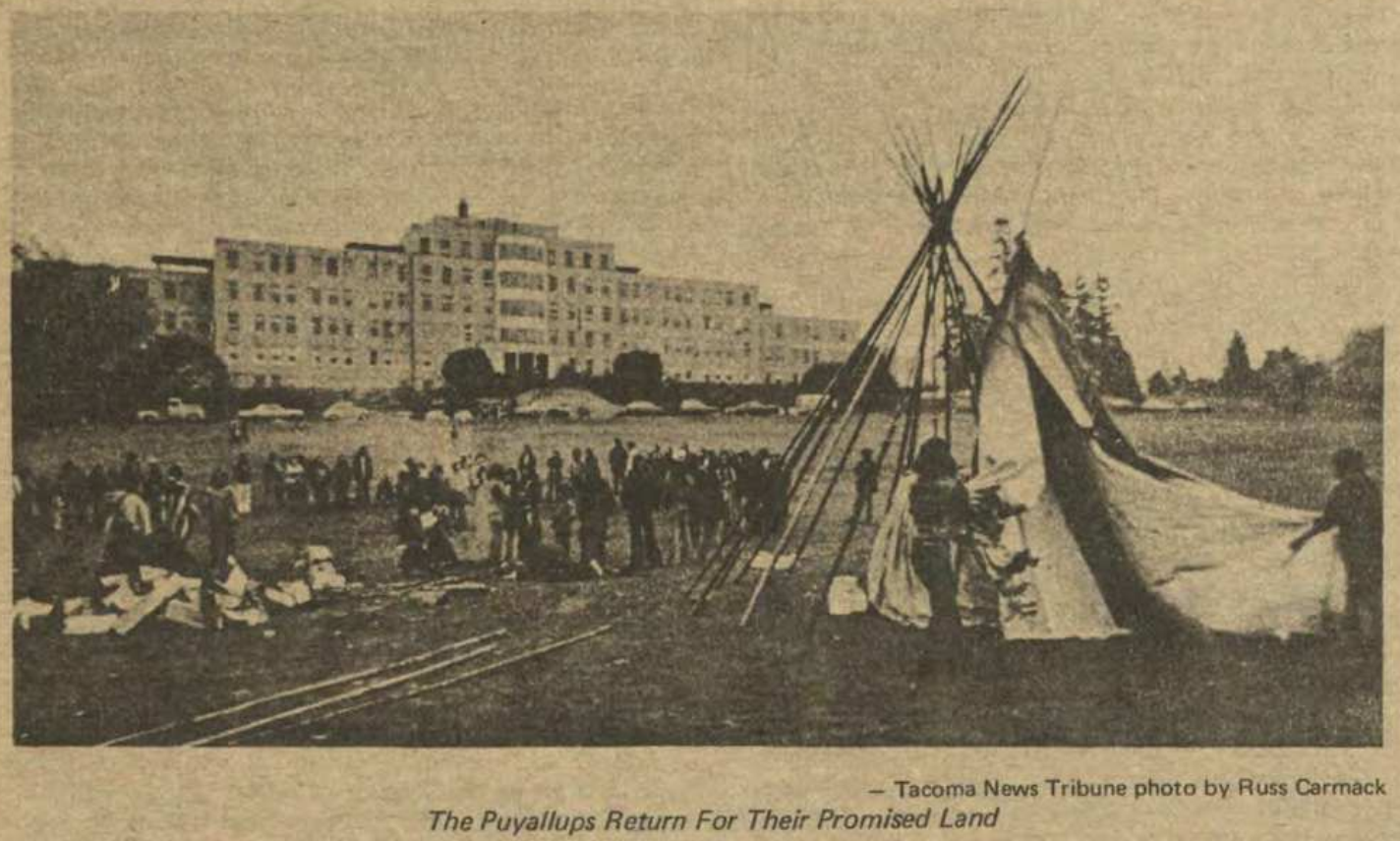

Photos from ‘The Freedom Socialist’, Fall 1976, Seattle

Washington State Squirms on Deal to Return Puyallup Tribal Lands

From ‘Akwesasne Notes’, Early Spring 1977

Tacoma, Washington — When the Puyallup Nation signed the Medicine Creek Treaty in 1857, they reserved to themselves 20,000 acres of land overlapping what is now the City of Tacoma and lying between it and Seattle in a valley that opens up on Puget Sound. Today, the Puyallup People own a little more than six acres.

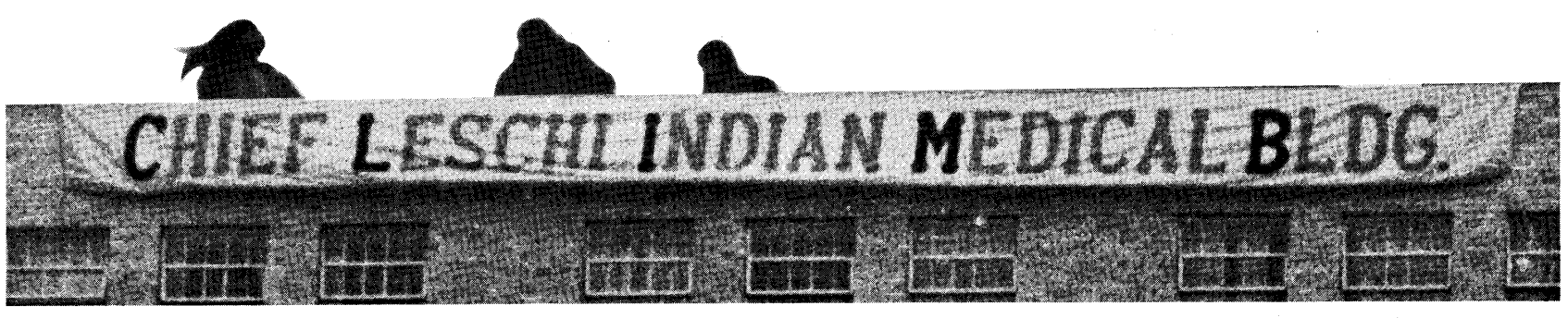

On the Puyallup land, the Cushman Indian Hospital had operated during the 1930s under a lease agreement with the U.S. Government. In 1939, Congress appropriated money for the purchase of the land and buildings for “Indian Sanitarium purposes” and a new 350-bed hospital was completed in 1943.

But gradually, with the implementation of the U.S. Termination Policy” cutting off “special relationships” the services of the hospital were at first curtailed, and then cut off completely. In spite of the fact that at the time, the infant mortality of Washington State native people was three times higher than that of the general population, and in the face of protests by local groups, the hospital and lands were declared “surplus” in 1960 so that the U.S. could transfer the hospital to the State of Washington the following year.

The Puyallup Nation continued to maintain a claim to the land. As of Autumn, 1976, negotiations between the Puyallups and the State had resulted only in an offer to allow the Puyallups to use a cottage on the hospital grounds as an Indian outpatient clinic. The State wanted to continue using the property as a juvenile detention facility.

Since that was the best they could do, the Puyallups said all right, and on October 23, about 200 Puyallups and guests were at the hospital, now known as the Cascadia Detention Facility, celebrating the opening of the new clinic. After dinner, approximately fifty native people descended from the 5th floor open house, accompanied by their own police force, and served an eviction notice on the assistant shift officer, seized the switchboard and assumed control of the building.

Resolution number 76-10-23 of the Puyallup Tribal Council declared the center to be “in possession of the Puyallup Tribe of Indians as its sovereign and rightful owners.”

“We’ve been involved in the legislative process for the past several years, and have now decided to act,” said Ramona Bennett, tribal chairwoman. “The hospital is ours — and we have it.”

The State immediately entered into serious negotiations and continued steadily until agreement was reached. At one point in the negotiations, after the director [Milton Burdman] of the State’s Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) reneged on an agreement, Ramona Bennett refused to negotiate privately, and transferred the talks to the main floor lounge, where native people, supporters, and the press could witness the proceedings.

Outside supporters responded quickly to the situation, and secured funds, food, supplies and favorable publicity for the occupation. Over 700 telegrams in support of the Puyallup Nation were sent to government officials, and even the press seemed sympathetic to the action.

But on October 26, the State went into Federal Court to seek an injunction against the occupation. The following day, U.S. Judge Morell Sharp said he would issue a restraining order enforceable by federal marshals effective at 4 p.m. on October 28. Burdman had said during the negotiations that the State of Washington would be willing to give up the facility eventually, but he wouldn’t “give it up with a gun”. Ramona Bennet remarked that the State was turning to armed federal marshals to get the Puyallups out.

Judge Sharp termed the occupation nothing less than an “inexcusable and disruptive affair” and said that if the Puyallups wanted the facility, they had other avenues to obtain the property.

Ramona Bennett disagreed. “I have been to Washington, D.C., at least 15 to 20 times in the last five years. I have been to the state and met with state senators and all they could do was look at me straight in the eyes and do nothing.”

The peaceful occupation lasted seven days. The Puyallups agreed to leave after Burdman promised the State would not press charges, but he did say the state might file a civil suit for recovery of damages or property lost as a result of the takeover.

Activists in the area remember that some of the same persons participating in the Cascadia occupation were involved in a similar occupation in 1974 at the Gethsemane Cemetery. That action had been called to press the Roman Catholic church for lands promised for Indian education.

In both cases, the Puyallup Nation addressed two problems: education and health care, both promised in treaties for land that they had transferred for specific purposes.

Significantly, the dramatic action of the takeovers accomplished something native people seem to be unable to do by “peaceful methods” — although the takeover was completely without violence or bloodshed. And significantly, no one, during the occupation of Cascadia, ever even tried the line that the Puyallups had no right to the property. Their rights seemed clear enough to everyone.

The final agreement specified that the state would work with the Puyallups for the return of the property, and the U.S. Government agreed to do everything administratively and legislatively necessary to facilitate the return. These promises were obtained in writing. Also agreed was that one of the buildings and six of the 30 acres of land would be turned over to the U.S. Government to be held in trust for the Puyallups for their use as a center for social services and health facilities.

However, the ink on the agreement was hardly dry when the State set up a legislative committee to fight against turning over the facility to the Puyallups. The State said it would refuse to honor the agreement unless the Puyallups reimbursed it for $1.7million it has spent on the facility.

Also

The Sea-Serpent, by Tekahionwake (1911)

Nisqually Proclamation or “Statement of Facts” (1965)

The Last Indian War, by Janet McCloud (1966)

Is the Trend Changing?, by Laura McCloud (1969)

Native Alliance for Red Power – Eight Point Program (1969)

Viewpoint of People Living on Puyallup River, by Ramona Bennett (1970)

Capitalism, the Final Stage of Exploitation, by Lee Carter (1970)

Bobbi Lee Indian Rebel, by Lee Maracle (1975/1990)

Puyallup evicts State from tribal property, by Sam Deaderick / The Freedom Socialist (1976)

The Freedom Socialist: Special Native American Issue (1976)

The Lost Days of Columbus, by Lee Maracle (1992)

Symbol of Indian rights being razed, by the Associated Press (2003)

Sovereignty, by Monica Charles (2005)

The Fish-in Protests at Franks Landing, by Gabriel Chrisman (2009)

Ramona Bennett Receives 2018 Bernie Whitebear Award, by Frank Hopper (2018)

Leonard Peltier’s Statement for Ramona Bennett (2018)

Yabuk’ʷali, the Tacoma ‘Fishing Wars’ bridge, is still the place for a fight, by Frank Hopper (2019)

Remembering Lee Maracle (2021)

The Day the Indians Took Over Seattle’s Fort Lawton—and Won Land Back, by Frank Hopper (2023)

Fighting for the Puyallup Tribe: A Memoir, by Ramona Bennett Bill (2025)