From ‘Akwesasne Notes’, Late Autumn, 1972

(Hank Adams is 29, an Assiniboine-Sioux who resides at Frank’s Landing, Washington. He has been active in fishing rights, and was himself the target of a late-night vigilante shooting in February, 1971. He was an acquaintance of Richard Oakes — and he wrote after his death this memoir.)

by Hank Adams

The death of Richard Oakes provides emphatic proof that there has been no ebb in the sickness and sea of violence which White America has maintained against Indian people throughout its history to sweep away the lives of our nameless and our renowned.

The flood of Indian deaths and murders has swept unabated throughout all the states — repeatedly in California, New York, New Mexico, Arizona, Pennsylvania, Minnesota and Washington — beyond American borders in Canada, Mexico and Brazil to cover the full expanse and breadth of the Native American continents. But in the United States the record of late is most foul and savage.

The pastime of killing Indians has not been surrendered from the self-esteemed “pioneer spirit” of White America in the 1970’s. Both policemen and private citizens, as vigilantes and as hunters, recognize no sanctions against stalking Indians and shooting them for any cause and on any occasion.

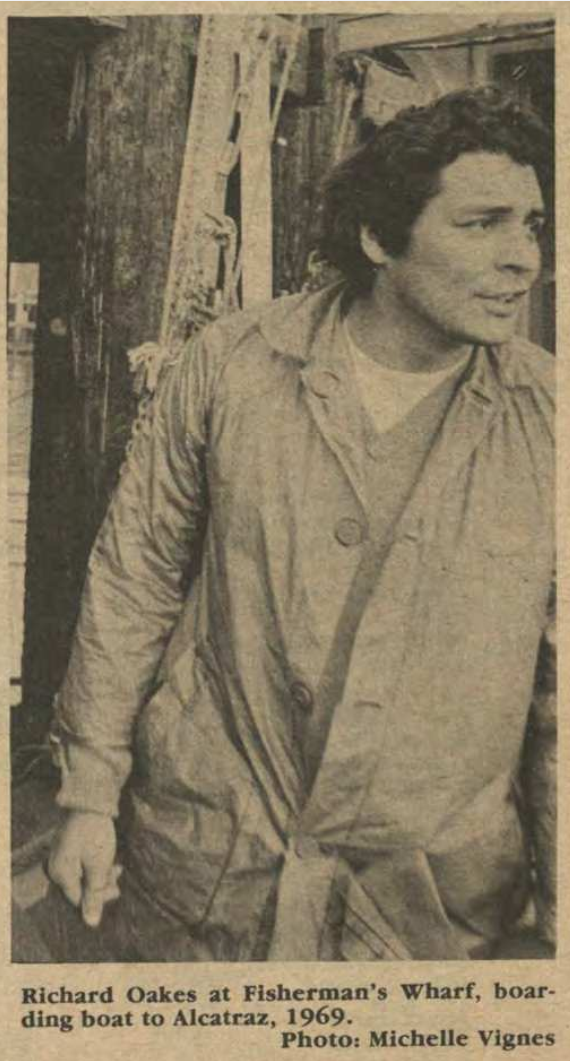

If Richard Oakes is only to be publicly identified with Alcatraz to the public by news media, then let the public remember that Alcatraz was instrumental in placing the needs and concerns of Indian people upon the national agenda. Remember that, despite its own failure in claims, Alcatraz had direct and powerful bearing upon the final results in settlement of claims with Alaska Natives, in return of Blue Lake to Taos Pueblo, Mt. Adams to the Yakimas, the establishment of DQU [Deganawidah-Quetzalcoatl University] in Davis, California, and the Seattle Indian involvement in the President of the U.S. “legacy of parks” decisions at Ft. Lawton, Washington.

For Indians, Alcatraz was never meant for confinement of people or of purpose nor to constrain the ideas or dreams of any. Its impact has been felt elsewhere.

Richard Oakes’ presence beyond Alcatraz and his influence upon many Indian people shall continue to live within the body and soul of Indian experience. Born to the American soil, and responding strongly to his peoples’ struggle and suffering upon it, the living spirit of Richard Oakes could not now die nor cease to be remembered upon American land.

Neither elegy nor eulogy can satisfy his life or death. But both can be looked to for generation within this land a legacy of protection for Indian people throughout it, a simple legacy promised Indian people during the infancy of the United States.

Can 50 states and 225,000,000 people now shield themselves from their own obligations under their Constitution and their treaty contracts to deny Indian people the protections due them? They can — it is obvious — because they have done it.

The question is simply whether the United States and its citizens shall continue doing so.

Also

Nisqually Proclamation or “Statement of Facts” (1965)

The Indian Claims Commission is illegal, unjust and criminal, by Karoniaktajeh (1965)

The Last Indian War, by Janet McCloud (1966)

Is the Trend Changing?, by Laura McCloud (1969)

Proclamation of the Indians of All Tribes at Alcatraz (1969)

Viewpoint of People Living on Puyallup River, by Ramona Bennett (1970)

We Have Endured, We Are Indians, by the Pit River Indian Council (1970)

Trail of Broken Treaties 20-Point Position Paper, by Hank Adams (1972)

The Six Nation Iroquois Confederacy stands in support of our brothers at Wounded Knee (1973)

Proclamation of the Puyallup Tribe on the Repossession of the Cushman Indian Hospital Lands (1976)

So I Started Fighting For My People, by John Waubanascum Jr. (1976)

The Brave-Hearted Women: The Struggle at Wounded Knee, by Shirley Hill Witt (1976)

Chronology of Oppression at Pine Ridge, from Victims of Progress (1977)

Mad Bear Wallace Anderson: Tuscarora Activist 1927-1985, by Kanentiio (1986)

How to Become an Activist in One Easy Lesson, by Joe Tehawehron David (1991)

Taking Back Fort Lawton, by Bernie Whitebear (1994)

The Fish-in Protests at Franks Landing, by Gabriel Chrisman (2008)

A Journey to Freedom: Richard Oakes, Alcatraz, and the Red Power Movement, by Kent Blansett (2018)

Yabuk’ʷali, the Tacoma ‘Fishing Wars’ bridge, is still the place for a fight, by Frank Hopper (2019)

Henry “Hank” Lyle Adams Obituary, by Northwest Treaty Tribes (2020)

We Need to Honor Richard Thariwasate Oakes, by Doug George-Kanentiio (2022)

The Day the Indians Took Over Seattle’s Fort Lawton—and Won Land Back, by Frank Hopper (2023)

The Killing of Richard Oakes, by Jason Fagone and Julie Johnson (2023)