(Printable PDF of this article via The Anarchist Library and Greek translation via ΔΙΑΔΡΟΜΗ ΕΛΕΥΘΕΡΙΑΣ)

By K. C. Sinclair

April 30, 2025

(minor corrections May 11)

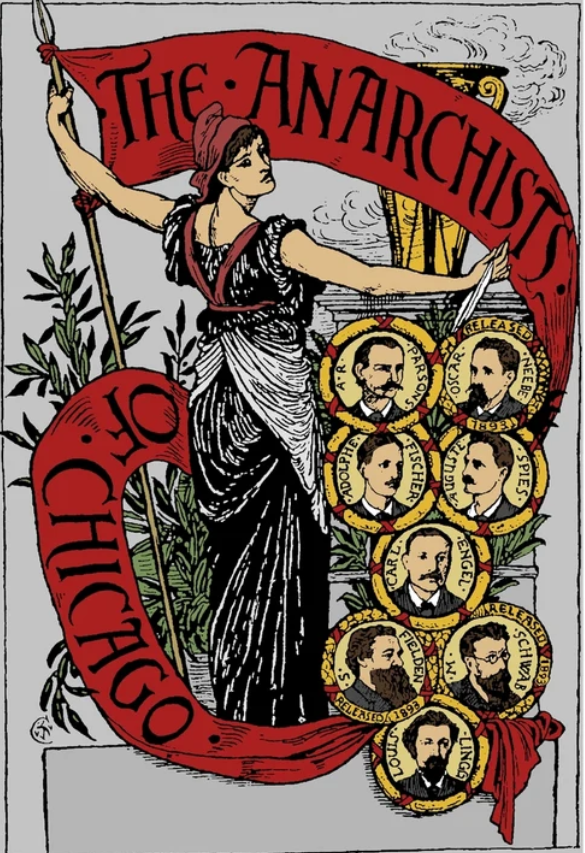

May Day honours the Chicago Haymarket anarchists who were martyred by the State of Illinois in 1887 in the struggle for the eight-hour day and communist anarchism.

A couple of years before they were executed, the Chicago anarchists had honoured some of the social rebels martyred before them, including Louis Riel, a leader of the Métis people.

Riel had been executed by the Canadian state in 1885 for treason, despite the fact that he was by then an American citizen and had been born in what’s now Winnipeg two decades before the country of Canada itself was brought into the world.

A memorial event in Chicago in November of 1885 paid “homage to the martyred heroes to human liberty, Julius Lieske and Louis Riel,” reported Albert Parson’s anarchist journal ‘The Alarm’.

The soon to be martyred anarchists August Spies and Parsons spoke on the occasion, as did their soon to be co-accused Samuel Fielden, who compared Riel to the infamous American abolitionist John Brown.

“There is need of such rebels today,” claimed Fielden.

‘The Alarm’ paraphrased Parsons and other speakers as having said that “In the fate of these martyrs we could all read our own doom at the hands of those who exploit and enslave their fellow men.”

In hindsight, this turned out to be a sadly accurate case of forward thinking.

This was also not the first time that the Chicago anarchists had addressed Indigenous peoples’ struggles or the character of colonialism. The Chicago comrades even had a direct connection to the Métis uprising via the person of Honoré Jaxon, who had been born to Euro-Canadian family but had been invited by the Métis to take part in the resistance in a secretarial capacity. After fleeing an insane asylum in Canada, Jaxon eventually made his way to Chicago and joined the workers’ movement there.

‘The Alarm’ had already published articles on the resistance as it was happening in 1885. The Chicago anarchists were unambiguous well-wishers for the Métis side of the fight.

“They are struggling to retain their homes of which the statute laws and chicanery of modern capitalism seeks to dispossess them,” one could read in ‘The Alarm’, “May their trusted rifles and steady aim make the robbers bite the dust.”

The year prior to this, ‘The Alarm’ had already made clear its stance on Indigenous autonomy.

“Left to themselves, left to the exercise of free will and personal liberty — anarchy — the red man would be alive and prospering, dwelling in peace and fellowship with his Caucasian brothers.”

Notwithstanding a dash of the ‘vanishing Indian’ trope, the stance of these non-Native anarchists on Indigenous autonomy was beyond any quibbling. It was only right that Native peoples keep their land and freedom. The invading capitalist society of private property was a scourge, not just to each individual American worker, but also to Indigenous communities and persons.

Forward by Way of Glancing Backward

Attention, for better or worse, to Indigenous peoples and the character of colonialism was not the domain of the Chicago anarchists alone. Honoré Jaxon, before arriving in Chicago, had met the anarchist Charles Leigh James in Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

In their discussion, James had drawn upon “his military reading for a remarkably farsighted discussion of the tactics which, in case of a renewal of the Metis struggle, might profitably be employed by a people weak in numbers, but possessing the facility of movement developed by the nomadic life,” according to Jaxon’s retelling.

It was James, in fact, who then arranged Jaxon’s contact with Albert Parsons in Chicago.

In his 1886 pamphlet ‘Anarchy: A Tract for the Times,’ James wrote that “governments are not of universal institution,” adding that “many primitive nations are without them.”

“One of these is the Esquimaux,” said James, “but there are also numerous others.”

Besides his use of an inappropriate exonym for the Inuit, James also claimed that they were more intelligent and civilized than other Native peoples that do have governments.

He went on to assert, sweepingly and wrongly, that “savages” are “very warlike, often living on human flesh, by the slave trade, or by pillage,” that Natives are further back in the timeline of the “progress of civilization.”

Yet, James held few illusions about the history of the American state. He suggested that his reader should follow up by reading books and articles that show that “our government, like others, sprang from war and oppression; that it was organized to drive out the Indians, to enslave the negroes, and to prevent others from sharing the spoil; that for a hundred years our flag enjoyed the honor of being the only one which fostered the growth and extension of slavery; and that since this accursed evil was abolished (because it did not suit northern capitalists so well as tenant farming) the same flag has the proud exception of being the only one under which landlordism is increasing.”

One of James’ suggested books was Helen Hunt Jackson’s 1881 ‘A Century of Dishonor,’ a book that would later also be quoted by Chicago anarchist Emily G. Taylor in 1901 in an article for the anarchist periodical ‘Discontent’, which was based out of the Home Colony in the State of Washington.

“It has been the claim of the Indian always that falsehood, perfidy and dishonesty characterize all transactions of the United States government with them,” wrote Taylor.

However, she also saw fit to laud, in the same article, the colonial official Thomas Jefferson, and to refer to her own ideological kin as “Jeffersonian anarchists.”

Taylor was apparently, and despite her sympathies for Indigenous peoples and attention to American colonial atrocities, unaware of or unconcerned with Jefferson’s explicit call for genocide against Indigenous peoples, not to mention the decidedly non-anarchist position of head of state, or the paradoxical nature of any so-called Jeffersonian anarchism or any anarchist patriotism for American traditions.

Yet, her and James’ folly in these instances only scratches the surface of that flip side to American anarchist criticism of colonialism, that is, American anarchist contempt toward Indigenous peoples, as displayed, for example, by other writers associated with the Home Colony.

There’s No Place Like Home on Native Land

Jay Fox, who had witnessed the Chicago Haymarket bombing before going on to take an active part in the colonization, under the aegis of the State of Washington, of the lands of Lushootseed-speaking peoples, wrote a vile racist screed titled ‘Civilized or Savage?’ in a 1914 issue of the Tacoma journal ‘Why?’

The State was founded on “barbaric, savage instinct,” claimed Fox.

“War is the delight of the savage, often his only means of subsistence,” he continued, as only a true American ignoramus and chauvinist could.

The fact that Fox would go on to abandon anarchism for statist socialism serves as little solace.

In an issue of Home’s ‘Discontent’ from 1900, Portland, Oregon anarchist Henry Addis had put his town’s present-day clueless hipsters to shame in an article titled ‘Savagery and Anarchy.’

Worried that non-anarchists conflated anarchism with anarchists wanting “to live like the Indians” and “go back to savagery,” Addis was only too happy to reassure his readers that this was not really the case.

Conceding that some anarchists had pointed to the greater happiness and freedom found among Indigenous peoples, Addis countered that whatever the truth behind those claims, he did not know of anyone who “really desires to take up the savage mode of living or see a general return to savagery.”

“Progress” and “civilization” were not all due to statist law, wrote Addis.

He claimed that “instead of a race of savages, we would have in Anarchy a race of art lovers and art producers,” as if Natives didn’t have their own artistic and cultural practices.

“In Anarchy we will enjoy greater liberty, or at least greater leisure, than is possible in savagery because production will be so much greater,” Addis adjoined, failing to see that greater production could also lead to greater drudgery, not to mention destruction of the biosphere.

In the same issue of ‘Discontent’, Chicago anarchist Lizzie M. Holmes, who had been at one time Albert Parsons’ assistant editor on ‘The Alarm’, made a spurious claim worse even than that made by Addis when she purported that “the savages had no more idea of equal liberty, and the endeavor to maintain it, than have the government lovers of today.”

If there were anarchists associated with the Home Colony such as James F. Morton Jr., who spoke out against racism in general, or Andrew Klemenčič who wrote back Home in support of Native Hawaiian (Kānaka Maoli) autonomy, there were also those spewing anti-Native sentiments, rendering as inconsistent Home’s overall stance on racism. Perhaps this shouldn’t be too surprising given Home’s existence as a project of colonization and a corporation under the laws of the State of Washington, with persons in the colony living in an “individualistic” and not “communistic” form, as advertised in the pages of Home’s own periodicals.

The anarchist colonists of Washington seemed to have little to no consciousness of their role as home invaders rather than mere home builders, and nary a clue that colonialist capitalism cannot be escaped for long, but must be confronted from the get-go, in communistic form, face to face with the enemy.

Liberty Enlightened by the New World

The anarchists of the Old World, even those who came to live for a time in America, also displayed contradictory thinking on colonialism and Indigenous peoples, much like their American-born counterparts.

English proto-anarchist William Godwin had written in 1793 that “little good can be expected from any species of anarchy that should subsist, for instance, among American savages.”

French exile and proto-anarchist Joseph Déjacque, once he’d arrived in the United States, had written against slavery and colonization in his periodical ‘Le Libertaire’, but with him, as with other American anarchists, a certain chauvinism and a particular perspective of Western progress persisted, even as he criticized colonial practices and praised Indigenous peoples.

“A socialist era” would have won the Natives over to “agricultural and industrial production; it would have brought them in, by the attraction of free and fruitful labour, to universal human solidarity,” Déjacque claimed in an article from 1860.

That same year, another writer by the name of F. Girard had an article featured in Le Libertaire on the brutality of colonialism as well.

Girard noted that “wherever civilization has spread across the globe, it has always been with the cross or the Bible in one hand and the sabre or the rifle in the other, treading in blood and strewing with corpses the road along which it has passed.”

This was seven years before the statist socialist Karl Marx, in his magnum opus, would write of colonialism and original accumulation, and how “capital comes dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt.”

Marx’s nemesis, the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, despite his declarations of support for self-determination for all peoples, in his 1869 ‘Letters on Patriotism’ called the Native peoples of the Arctic “wretched” and asked “what could be more miserable and less human” than an Arctic Native person’s existence.

The French-language Swiss anarchist periodical ‘Le Révolté’ in 1884 printed an article titled ‘Nos Colonisations’, in which it was argued that “No people has the right to oppress another; let each one arrange his home as he sees fit.”

However, the article also wrongly claimed that “the worker has nothing to gain from these so-called conquests of civilization,” eclipsing some very important things European workers did in fact have to gain from colonizing the New World, namely, cheaper land and a new life.

This was the same year that statist socialist Friedrich Engels would publish his American and Indigenous influenced book ‘Der Ursprung der Familie, des Privateigenthums und des Staats,’ not translated into English until 1902, as ‘The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State,’ published by Chicago’s Charles H. Kerr & Company.

In 1886, the Paris Communard turned anarchist Louise Michel would publish her ‘Mémoires’, in which she remarked on her forced exile on the island of Kanaky and her support for the Indigenous resistance that erupted during her stay there.

“Well, yes, those who accused me, at the time of the revolt, of wishing for them [the Kanaks] the conquest of their freedom, were right,” Michel admitted, “Let’s end the superiority that only manifests itself in destruction!”

Nevertheless, Michel maintained progressivist attitudes too, as well as pessimism regarding the Kanaks ability to beat the French and maintain Kanak culture without mixing it with that of the French. She failed to consider that her European notions of betterment could be the enemy of good, and that Native peoples could be more persistent than she’d pondered.

Twenty Four Hours for What We Will

Nowadays, May Day is deemed to be all about the dignity of labour, but the Chicago Haymarket anarchists were a little more farseeing than that, contending with colonialism and the land, not just with work. The eight-hour day was a scrap, in both senses of the word, along the way to brighter days and a different way of life. The struggle was not just to work less, but ultimately to work not at all. The goal wasn’t just to seize the workplace, but to reclaim land and freedom.

Even some of today’s anarchists still fail to deal with colonialism and the struggles of Indigenous peoples in any rigorous fashion. They’re too busy reducing anarchism to a mere aesthetic, slapping a red and black patch onto a European state soldier’s uniform and calling it anarchist pragmatism.

In contrast, Emily G. Taylor of Chicago, in critiquing American militarism, had once asked, in now archaic language, “Which Makes the Greater Savage, the Blanket or the Uniform?”

While it’s only right to celebrate the moments when historical anarchists tackled capitalism and colonialism, it’s also never too late to own up to our predecessors’ (and our contemporaries’) mistakes, be they regarding colonialism or anything else, and facing up to them is the only way to truly move forward.

The American anarchist Voltairine de Cleyre, in her Haymarket memorial oration delivered in 1901 in Chicago, bravely admitted that at the time of the tragic events, she had thought the anarchists guilty and believed that they should be hanged, but over time had learned from her mistake and embraced their struggle. She repeated this kind of humility in a 1912 article where she described her work in Chicago, alongside the old rebel Honoré Jaxon, to garner support for the Mexican Revolution and its anarchist protagonists. The anarchist movement was not doing enough in this direction, in her estimation.

“I who write have been as much to blame as any,” she offered, “let me shake off my blame by stirring you to awaken now.”

We can learn much from the humility of comrades like de Cleyre and move forward by acknowledging and correcting the missteps behind us.

For the 1986 centennial of the Haymarket affair, Chicago social rebel Franklin Rosemont, to his great credit, published the incredible and invaluable ‘Haymarket Scrapbook’, reviving the connections between the Chicago anarchists and the struggles of Native and Black peoples, some of which have been mentioned in this article.

Two years prior, the respected historian of anarchism Paul Avrich had published his magnum opus, ‘The Haymarket Tragedy’, a hefty and inspiring text that’s as readable as it is relevant.

As state repression in America currently escalates in the context of the heightened genocidal attacks on the Indigenous people of Palestine, and as thought itself is turned back into a crime, as it was against the Chicago Haymarket anarchists, the task of turning history into a practical tool is left to us to pick up and run with.

Not run as in run away to a settler colonial land project, but run as in dash headlong into the fray in whatever way seems most thoughtful and practical, in solidarity with all oppressed peoples, with the awareness that the freedom of other people is also our own freedom, that an injury to one is still an injury to all, that maybe we’re still crazy after all these years.

Also

An Appeal for Justice, by Louis Riel (1885)

A Martyr, from The Alarm (1885)

Record of the International Movement [on Julius Lieske], by Eleanor Marx Aveling (1885)

The Famous Speeches of the Eight Chicago Anarchists in Court (1886)

Autobiographies of the Haymarket Martyrs (1886-1889)

The Philosophy of Anarchism, by Albert Parsons (1887)

Life of Albert R. Parsons, by Lucy E. Parsons (1889)

Which Makes the Greater Savage, the Blanket or the Uniform?, by Emily G. Taylor (1902)

The Curse of Race Prejudice, by James F. Morton Jr. (1906)

A Rebel May Day, from Industrial Worker (1909)

A Reminiscence of Charlie James, by Honoré J. Jaxon (1911)

Time is Life, by Vernon Richards (1962)

Viewpoint of People Living on Puyallup River, by Ramona Bennett (1970)

Proclamation of the Puyallup Tribe on the Repossession of the Cushman Indian Hospital Lands (1976)

The Haymarket Tragedy, by Paul Avrich (1984)

Anarchists and the Wild West, by Franklin Rosemont (1986)

Overshadowed National Liberation Wars, by Howard Adams (1992)

Civilization vs Solidarity: Louise Michel and the Kanaks, by Carolyn J. Eichner (2017)

Why America’s First Colonial Rebels Burned Jamestown to the Ground, by Erin Blakemore (2019)

Unknowable: Against an Indigenous Anarchist Theory, by Klee Benally, Ya’iishjááshch’ilí (2021)

Louis Riel: Hero, heretic, nation builder, by Darren O’Toole (2022)

Clarity Contra Complicity, by K. C. Sinclair (2025)

Anarchism and Revolutionary Defeatism, by K. C. Sinclair (2025)

Anarchists & Fellow Travellers on Palestine

Anarchism & Indigenous Peoples

“Dissolve the army and immediately withdraw from Morocco.”

Workers at the CNT-FAI rally in Barcelona on May Day in 1931 (from ‘Durruti in the Spanish Revolution‘)