[李堯棠; pinyin: Lǐ Yáotáng; 25 November 1904 – 17 October 2005), better known by his pen name Ba Jin (Chinese: 巴金; pinyin: Bā Jīn) or his courtesy name Li Feigan (Chinese: 李芾甘; pinyin: Lǐ Fèigān)]

From ‘Cienfuegos Press Anarchist Review’, Number 4, 1978, Sanday, Orkney

Philip Short is the first non-Chinese foreign correspondent allowed to visit China’s greatest living novelist and writer since the mid-1960’s. He broadcast his impression from Peking (23/11/77) on the BBC Radio 4 programme “From Our Own Correspondent.”

Said Mr. Short,

There’s an unspoken convention whereby Chinese never receive foreigners at their homes. So instead of my going to see Pa Chin [AKA Ba Jin], he came to see me. A short, compact man, at 73 a little stooped and tottery with a brush of grey hair and an unquenchable spirit. He’s lived in Shanghai for more than 50 years, but still speaks in the heavy brogue of his native province of Serchwan [].

In the 20s, like many young Chinese intellectuals of his day, he went to Paris to study, and it was there partly out of homesickness, as he tells it, that he wrote his first novel Destruction [灭亡]. Four years later, it was followed by a second book Family [家], a vivid and masterly portrait of the suffocating pressures of a traditional Chinese household, and the ultimately successful efforts of one of its younger members to break out into the real world of China outside.

It influenced a whole generation of Chinese youth to turn its back on the old order and search for something new. And this week after a gap of 20 years, it’s being republished here as one of the first of a series of modern Chinese classics. Of all Pa Chin’s novels, Family [家] is the only one to have been translated into English, though until I mentioned it, he didn’t know that a translation existed. He’d written it, he said, because he wanted to do something about the fate of his contemporaries.

At that time he was an anarchist who coined his pen-name Pa Chin from the first two characters of the Chinese renderings of the names of the Russian anarchists — Bakunin and Kropotkin — and decades later his anarchist’s sympathies along with his insistence that writers must have the courage of their convictions, rather than just following the official line, was thrown back at him when he disappeared down the maw of the Cultural Revolution.

What happened then, he recalled with a wry humour, that helps to explain how he survived when others didn’t. One of his best friends, the writer Lao She [老舍] committed suicide. He was one of the old intellectuals Pa Chin said, when the Red Guards rebelled he didn’t understand that he couldn’t accept it. He himself was paraded before dozens of struggle and criticism meetings at which thousands of people shouted imprecations at him, and his books were denounced as “big, poisonous weeds.” There were so many meetings, he said, because he’s written so many books. It was a time when he thought he might have been less prolific.

While that was going on, he was made to work cleaning out the Writers’ Association drains, which he said, at least had the advantage that he knew what to do when his sink was blocked up. This continued for three years, during which, far from abandoning hope, he taught himself Italian to keep his mind alive. Then in 1969 he was given, as he put it, an opportunity which he’d not have had before the Cultural Revolution to do agricultural labour. And the next three years he spent in the countryside, until in poor health in late 1972 he was permitted to return to Shanghai where his wife [Xiao Shan / 萧珊] was dying.

A year later he was allowed to resume living at home and to start doing translations. But he couldn’t publish them, and many of his old friends were afraid to visit him because officially he was still an enemy of the people. And that, he said, he remained, despite protection from Premier Chou En-lai [周恩来], until the fall of the radical leaders in October last year.

As for the future, the main task, Pa Chin said, was to eliminate the radicals’ influence on literature; and in particular their insistence that novels must be heroic from beginning to end, which he declared had had a very bad influence on China’s young writers. But he seemed uncertain how much creative freedom writers would actually have, saying that certain questions remained to be clarified.

And on that I didn’t press him. For his own work he has a new translation of Turgenev‘s Virgin Soil due to appear next year, and before he’s 80, which he thought was as long as most writers remained sensible, he wants to write two last novels, one of them set amid the upheavals of the past decade of radical dominance. And there is a logic in that. For his two great books — Family [家] and Cold Nights [寒夜] about the rottenness of Kuo Mintang rule in the forties, were also motivated, as he explained it, by his loathing of what he saw as evils. [some partially missing text about Cold Nights]

And to all of this there is a postscript. We’d been talking in my hotel room, and afterwards a young waiter came in to clear away when his eye happened to fall on a book, which Pa Chin had signed for me. It’s the only time I’ve ever seen anyone literally speechless. He pointed at it, looked in disbelief at the door and struggled to get out the words. “Pa Chin,” he said eventually. “Was that really him?”

Peking, November 23rd, 1977

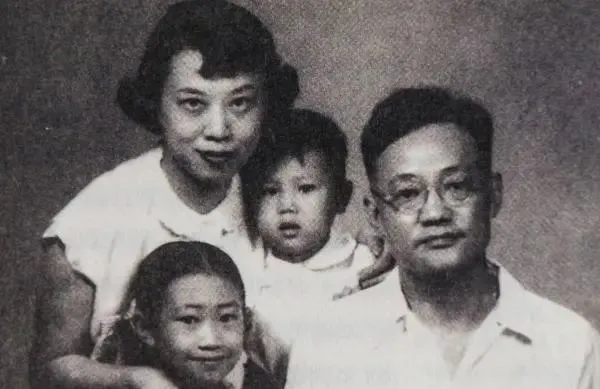

Xiao Shan and her children Li Xiaolin and Li Xiaotang, and husband Ba Jin

Xiao Shan and her children Li Xiaolin and Li Xiaotang, and husband Ba Jin

Also

Nationalism and the Road to Happiness for the Chinese, by Ba Jin (1921)

Chiang Kai-Shek and the Communists in China, by Marie Louise Berneri (1942)

Malaya, by Albert Meltzer (1948)

The Chinese Anarchist Movement, by Robert Scalapino and George T. Yu (1961)

Anarchism in the Chinese Revolution, by Arif Dirlik (1991)

Chinese anarchists in the 1920’s USA, by Mitch Miller and Joseph Spivak (2006)

The Best Feminist You’ve Never Heard Of: He-Yin Zhen, by Zoe Baker (2021)

Translations of Selected Articles of Pingden, by Liao (2025)