Published separately by the US Civil Rights Commission and Akwesasne Notes (Early Summer 1976)

By Shirley Hill Witt [Akwesasne Mohawk Nation, Wolf Clan], Summer 1976

“The lineal descent of the people of the Five Nations shall run in the female line. Women shall be considered the progenitors of the nation. They shall own the land and the soil. Men and women shall follow the status of their mothers.’ You are what your mother is; the ways in which you see the world and all things in it are through your mother’s eyes. What you learn from the fathers comes later and is of a different sort. The chain of culture is the chain of women linking the past with the future.

As litany in every calling together of the Longhouse Iroquois people, these words are said in order to recall the original instructions given to humans at the time of our creation: “We turn our attention now to the senior women, the Clan Mothers. Each nation assigns them certain duties. For the people of the Longhouse, the Clan Mothers and their sisters select the chiefs and remove them from office when they fail the people. The Clan Mothers are the custodians of the land, and always think of the unborn generations. They represent life and the earth. Clan Mothers! You gave us life — continue now to place our feet on the right path.” — The Iroquois Great Law of Peace (Kaioneregowah)

Anna Mae Pictou Aquash was born and raised on the Micmac reserve called Shubenacadie in Nova Scotia. Her sister says that life in Shubenacadie is much better than on the Western reserves and reservations in the U.S. and Canada: at Shubenacadie, everyone is on welfare. Since no one has a job — only pickup government jobs for perhaps 5 months out of the year for a few — having everyone signed up and receiving welfare is quite a social accomplishment for the bureaucracy.

Unlike so many Native children in Canada and the United States, Anna Mae was not removed from her family and shipped hundreds of miles away to a boarding school. She escaped the aching loss of family and she also avoided the indoctrination efforts of the boarding schools. Native children by the hundreds in both countries serve time for as many as 12 years in federal schools geared to their gradual and eventual assimilation of the Anglo way of life, the ultimate solution to the “Indian Problem.”

Anna Mae did not have to choose between being a secretary, a domestic servant, a hospital attendant, or a cosmetologist — the traditional range of options for boarding school girls. She did not view her future as a choice between being employed as a menial or living on a reservation where even those minimal skills are largely superfluous.

She had dreams to be educated someday and to get a job working with children, maybe as a teacher. To be a teacher of children is at the same time both the most prosaic and the most awesome of aspirations: for someone from Shubenacadie to aspire to an Anglo certified teacher’s degree was like seeking the Nobel Prize. But instead, Anna Mae Pictou dropped out of school in the 9th grade, perhaps because of the change from an all-Indian reserve school to a local mixed Indian and white high school.

In time, with now a husband and two daughters, life on the Micmac reserve became too oppressive, too devoid of options. An essential ingredient was in short supply: hope.

A friend explained how Anna Mae felt: “There isn’t much hope in looking towards potato fields and blueberry fields for a proud people. She didn’t want her children to suffer in life as she did. The way the world is made her suffer, because she was sensitive and had strong feelings.”

There are traditional migratory patterns that trace the paths of Native Americans from their home communities to one city, and then perhaps to another city and another — and of course, back again. Boston is a funnel from Canada and much of the Northeast for those who do not go directly to New York City and Brooklyn. Anna Mae went south to Boston with her family when life at Shubenacadie failed to answer their needs. She got a job as a teacher’s aide in a prekindergarten child care center for Black children in the Roxbury area, even with her lack of education.

She became involved with the Boston Indian Center and was sent by the Center to Washington, D.C., at the time of the Trail of Broken Treaties when the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs building was taken over. The established media focused their attention on who they judged to be the leaders and organizers — that is, Native American males. Their cameras and tape recorders only grazed the faces of Martha Grass from Oklahoma or Ann Jock from Akwesasne or the many strong women who like Anna Mae Pictou breathed life into an idea.

The women who went to Washington expressed their purpose in this way:

We are the gwen non gwa weh, the Indian women of this continent. From the female side of life, we extend our life support to our children of these territories in North America. We have much work to do. Our position is with our people and nothing can stand in our way to fulfill our job: to tell the people of this earth of our survival and to expose the genocide being done to Native American nations by the U.S. Government. We must do this for we care for our children.

Yet the love of all people for their children has not always been attributed to Native Americans by whites, nor has the Indian commitment to the survival of Indian children always been recognized. For Native Americans since the Pilgrims arrived, such assumptions have far too often led to the wholesale abduction of their children, to be raised by Anglos in their own image. Native Americans have seem no diminution of this fearsome practice.

Bernice Appleton, an officer of the Native American Children’s Protective Council chartered in Michigan, observes, “There is a shortage of white babies for adoption, so since not too many whites want Black babies, they are coming for the next — and that’s Indian. These agencies are going into Indian homes and telling them their homes are unfit because they have two children, or three children, sleeping in one bed… It isn’t necessary for Indian children to have one bed apiece. I don’t even think it’s good for children to sleep apart. Our children learn sharing right from the start.”

In Canada, children needing homes are removed from their communities and extended families. A 1975 report published by the American Indian Treaty Council Information Center states, “Often relatives are available to care for children, but they cannot get financial support [from agencies] because the children are related to them. However, the agencies have to pay the white foster parents for the children, often adding on additional subsidy because the children are Indian and are ‘hard to manage’.”

Anna Mae returned from her experience in the Washington portion of the Trail of Broken Treaties a renewed woman, dedicated and determined to share in the hemispheric struggle of Native Americans. “She had been in the struggle for a long time for her people,” said Nogeeshik, who later became her second husband. He added:

Many Micmac people knew that they could go to her for help, a place to sleep, money, or whatever she had… She loved her children very much. It was a great sacrifice for her to be away from them—they were very close — but she wanted change to come to Indian people right away. This is why she fought and struggled so hard, and if everyone did that, maybe her children would not have to go through the same difficult things that she was forced to…

As an Indian person she wanted her people to be recognized by other Indian people who never heard of the Micmac. Her people had European contact long before Western tribes had. It is only through their diligence and tenacity they have been able to survive to this day. She realized that with the onslaught by whites, the Micmac were disappearing. Her people, the Micmacs, strongly maintain some of their cultural ties, and most important, their language. This is where her fight began…

She wanted it known what a poor people the Micmac of Nova Scotia are with little jobs and work, discriminated against through law enforcement, education; the reality of what cluster homes produces; the people’s shift from productive areas to poor areas where drinking and oppression became an everyday thing. That is why she was so strong in the efforts of the movement. She has had difficulty in trying to make other people aware of this. What she was saying in her efforts was that the Micmacs faced these problems 200 years ago and that she understood what the Western tribes were now faced with. In that way, she was years ahead of her times. She was able to see objectively a lot of the problems that the Western tribes are now facing.

And so, before long she went West, having returned her daughters to Shubenacadie, to their other “mothers,” Anna Mae’s sisters. Many tribal peoples consider a woman’s sisters as natural mothers to her children. Such sharing of maternal duties allows for a wider range of activities on the part of any single “mother.” In such cultures, it is assumed that others can love and nurture a child as much as the woman who bore it.

In the winter of 1973, the Second Battle of Wounded Knee began on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota. Traditional Oglala leaders had organized themselves to oust Dick Wilson, the tribal chairman, who was accused by many of instituting one-man rule and oppressing all opposition.

In February of 1972 the traditional Oglalas asked for the assistance of the American Indian Movement, a loose-knit group of activists that included many Oglalas. In November 1972 AIM was banned from the reservation by Wilson. In February 1973 three tribal council men filed impeachment proceedings against Wilson for the fourth time since his election 10 months earlier.

Wilson called for assistance from U.S. Marshals and the FBI, who arrived in Pine Ridge in February 1973, shortly before the impeachment hearing was to begin. Wilson them postponed the hearing from February 14 to February 22. The hearing was held amidst charges that it was rigged; the impeachment motion failed. Wilson’s opposition, several hundred strong, met immediately afterward to decide what to do.

Feeling that all legal avenues were now closed to them, the protesters proceeded to Wounded Knee to assert their right to democratic self-government. They intended to create a base from which they could negotiate with the Pine Ridge administration. By all accounts, none had any idea their stance would result in a situation which evolved into a full-scale paramilitary confrontation.

The Second Battle of Wounded Knee found Anna Mae among the many young and old women who shared a common denominator: the loss of patience. Regina Brave put it into words.

WE’RE TIRED!

We’re tired of seeing our men driven by despair, turn to alcohol, commit suicide, or end up in penal institutions!

We’ve reared our children only to see them brainwashed by an alien system with a genocidal policy which destroys our language, customs, and heritage!

We’re tired of seeing our brothers and sons go off to war only to come home and be slain by United States Government forces!

After 483 years… we’re tired… we’re damn sick and tired.!

So, we’re standing up next to our men. We’re standing up and taking up the battle here and now to protect our young so their unborn can know the freedom our grandparents knew.

The future of our young and unborn is buried in our past. We are today who will bring the rebirth of spiritualism, dignity, and sovereignty!

We are Native American Women!

Regina Brave, Oglala Lakota, defender of Wounded Knee in 1973

Throughout the siege of Wounded Knee women organized, planned, provided support and materiel, and, in effect, gave continuity to the endeavor. They traveled back and forth through the battlelines, backpacking in the food to sustain the AIM defenders. In Dakota tradition, they were called “Brave-Hearted Women.” In the American media, these women were ignored. The cameras hummed and clicked upon the faces of male AIM members. And after the battle, the AIM men were arrested, neutralized, or eliminated by one means or another. The white male enforcement officers, blinded by their own sexism, failed at the time to recognize the power of the women, and that the heart and soul of the women would carry the movement forward.

With so many males no longer functional, AIM more now than ever became a woman-run organization. One older woman observed, that, “It is sad how few men are involved in the movement. It’s hard for just us little old ladies with our pop bottles [to sustain it].” The AIM offices would be run by women as they had at the start of the movement. One said, “we are here because there is work to do.” Women, it is said, are less apt than men to draw barriers between people; you are welcome if you want to help in the struggle.

The Wounded Knee aftermath continued like devastating seismic shocks bringing repercussions of violence and death. In a siege in [June] 1975 upon AIM members — mostly women and children — one Native man [Joseph Stuntz] and two FBI agents were killed.

According to weeks of testimony at the 1976 Cedar Rapids, Iowa trial of two AIM members, a full-fledged military operation was launched that left the Pine Ridge Oglala Sioux Reservation a living hell while some 150 FBI agents ransacked homes and ran search parties through fields and woods. BIA police report that by late 1976, 47 people had been murdered in this bleak poverty-stricken corner of South Dakota since Wounded Knee. Wilson’s political faction acted out its burning hostility against AIM and the traditional Oglala people who support it with an unrelenting series of beatings, shootings, car “accidents,” and other destruction which continues to this day.

Dino Butler, since acquitted of the charge of first degree murder of one of the FBI agents, tells another chapter in Anna Mae’s life:

Anna Mae Aquash was arrested at Rosebud Indian Reservation, South Dakota, on September 5, 1975. One hundred to one hundred fifty agents invaded Crow Dog’s Paradise and Al Running’s residence simultaneously. The FBI agents identified her immediately as Anna Mae Aquash and though there was no warrant for her arrest, they handcuffed her and placed her under arrest. She was transported to Pierre (S.D.) immediately where she underwent intensive interrogation for 6 or 7 hours, being questioned about the June 26, 1975, Oglala shootout between Native Americans and foreign Americans. She could not tell them anything because she was in Council Bluffs, Iowa, that day. The FBI agents made her the same offer they made me that day in Pierre after I, too, was arrested and transported from Al Running’s home — “cooperate and live; don’t cooperate — die.”

Anna Mae described her encounter with the FBI agents. “While I was standing there with a group of women, waiting, I was being verbally harassed by some of the agents. They were implying that they had been looking for me for a long time and that they were very pleased that they finally found me.”

Becoming Targets

Now that essentially all the male AIM members and supporters made prominent by the media, were effectively neutralized — in hiding, in jail, or dead — the mid-70s saw the targeting of women by enforcement officers and vigilantes. A foreshadowing of this occurred in the Northwest where Native peoples have struggled to preserve their traditional fishing rights.

“In Washington State,” one of the embattled survivors explained, “women have had to stand in [the men’s] place because we are supporting them and supporting our unborn. There have been issues, like fishing rights, when our men were put in jail and all that was left was women to go out and fish. Yet the women were still treated the same, with the same harassment from the police, being beat up and going to jail, even women with children.”

Nor was death a stranger to the women along the banks of those rivers — sudden, violent death.

In Wagner, Sioux Falls, Custer, Gordon, Rapid City, and, of course, Pine Ridge, greater and greater pressure came down upon women as a new point of attack. Gladys Bissonette observed that, “Everytime women gathered to protest or demonstrate (peaceably), they always aim machine guns at us, women and children.” With the male leaders made ineffectual, the AIM organization did not die. Nor did the greater movement for Indian rights, of which AIM has always been but a part. But as the Cheyenne people say:

A nation is not conquered

Until the hearts of its women

Are on the ground. Then it is done, no matter

How brave its warriors

Nor how strong its weapons.

The women patriots who bore a heavy share of the task of physical and spiritual survival of their people through all the years would not now surrender. The list of Native women who have been harassed, jailed, beaten, stabbed, and shot grew long in this new campaign.

On February 24, 1976, the body of a young woman was found as it had lain for many days and nights along the highway north of Wanblee. The BIA contract coroner declared that death was caused by exposure; that is, natural causes. The FBI agents severed the hands from the body and forwarded them to Washington for identification. A week later the body was buried in an unmarked grave at the Holy Rosary Mission. By that time, however, the identity of the young woman was known and communicated to family and then to friends. They insisted on an exhumation and a second autopsy. This time the autopsy performed by their own examiner read differently:

On the posterior neck, 4 cm. above the base of the occiput and 5 cm. to the right of the midline is a 4 mm. perforation of the skin with a 2 mm. rim of abrasion surrounded by a 1.5 x 2.2 cm. area of blackish discoloration. Surrounding this is an area of reddish discoloration measuring 5×5 cm. This area is grossly compatible with a gunshot entrance wound.

On page 4 there is the sentence: “Removed… (from the brain) is a metallic pellet dark grey in color grossly consistent with lead.”

March 14, 1976, dawned windy, flinging snow upon those who had come to bury Anna Mae Pictou Aquash. “Creation was unhappy,” one woman said. Some women had driven from Pine Ridge the night before — a very dangerous act — “to do what needed to be done.” Young women dug the grave. A ceremonial tipi was set up. Anna Mae’s naked body was removed from the morgue’s body bag. Her severed hands and their ten finger tips, also severed, were returned to her. The women clothed her in a ribbon shirt and jeans with a jean jacket emblazoned with the AIM crest and an inverted American flag on the sleeve. Beaded moccasins were put on her feet.

A woman seven months pregnant gathered sage and cedar to be burned in the tipi. Young AIM men were the pallbearers: they laid her on pine bows while the religious leader spoke the sacred words and performed the ancient duties. People brought presents for Anna Mae to take with her to the Spirit world. They also brought presents for her two sisters to carry back to Nova Scotia with them to give to the orphaned daughters.

The funeral of Anna Mae Pictou Aquash at Pine Ridge

Finding The Truth

The executioners of Anna Mae did not snuff out a meddlesome woman; they exalted a Brave-Hearted Woman for all time. The traditional leaders of Oglala released a statement about her death before the second autopsy was performed:

We demand that a full investigation be conducted about the causes and circumstances of the death of Anna Mae Pictou Aquash. We do not believe she died of exposure and are certain foul play is involved. The way in which the BIA police and the Federal Bureau of Investigation have handled this investigation makes it appear to be more of a coverup than an investigation into the death of still another Indian on Pine Ridge Reservation. If she was identified by her fingerprints, why did it take so long? Why was she buried before she was positively identified? Or, did the police and Federal and tribal authorities know who she was?

Anna Mae worked hard serving her Indian people and assisted in our efforts to shed the shackles of government paternalism. She is with us. In her blood in Oglala. We consider her a friend. So, therefore, we are concerned because we feel that her involvement as our ally probably brought her death. We are prepared to conduct our own investigation and we feel that a report from an independent coroner is essential.

Dr. Brown, the pathologist who conducted Anna Mae’s autopsy, also provided the BIA and FBI with the information they knew about the death of Buddy Lamont, killed by Federal forces in Wounded Knee in 1973, and Pedro Bissonette, killed by the BIA police in November (sic October) of 1973. Therefore, we question Dr. Brown’s independence and credibility. We want to know the truth about Anna Mae’s death and the possibility of the government’s involvement in it.

Anna Mae Pictou was respected and loved by the people of Oglala. We mourn her and we urge all law abiding citizens to demand the real truth about her death.

The brave-hearted women who remain to face the dangers of the Indian world have sadly been given a martyr, Anna Mae of Shubenacadie, Boston, Washington, St. Paul, Wounded Knee, Los Angeles, Oregon, and finally a frozen grave site on a ridge in Oglala. Among the Iroquois, it is the women who decide when the people will go to war, because, when the war is done, it is the women who weep. Will the brave-hearted women decide that, with Anna Mae’s death, the war is over? Or will they decide with Lorelei Means who declares, “Hell, we’re struggling for our life. We’re struggling to survive as a people.”

Anna Mae Pictou Aquash faces the sun’s first light with the white, black, red, and yellow streamers flapping overhead on poles placed in the four sacred directions cornering her grave. The brave-hearted women have decided there will be war.

– – –

Shirley Hill Witt, an Iroquois, is director of the Mountain States Regional Office of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. The views expressed in this issue are her own and not necessarily those of the [US Civil Rights] Commission.

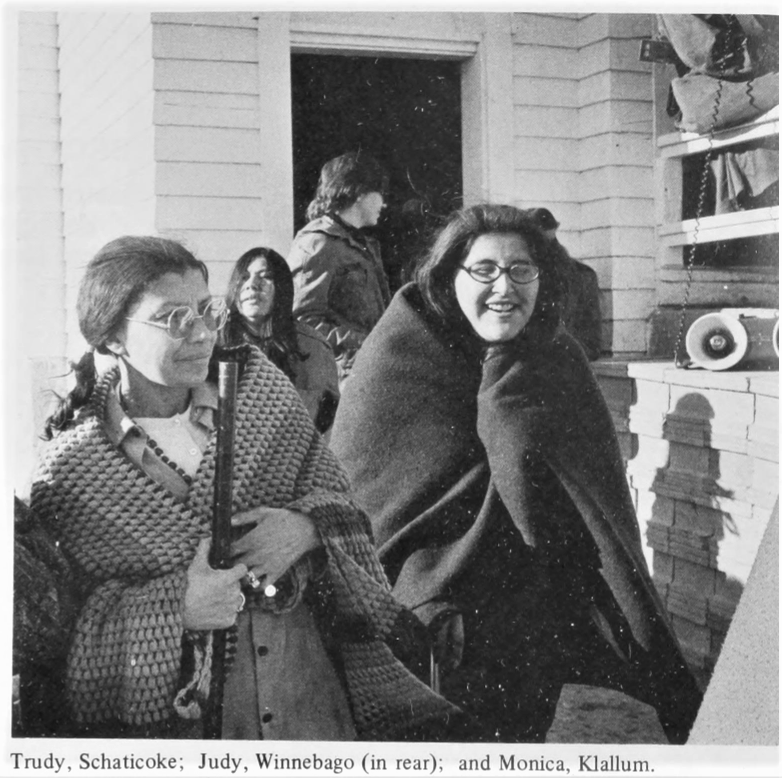

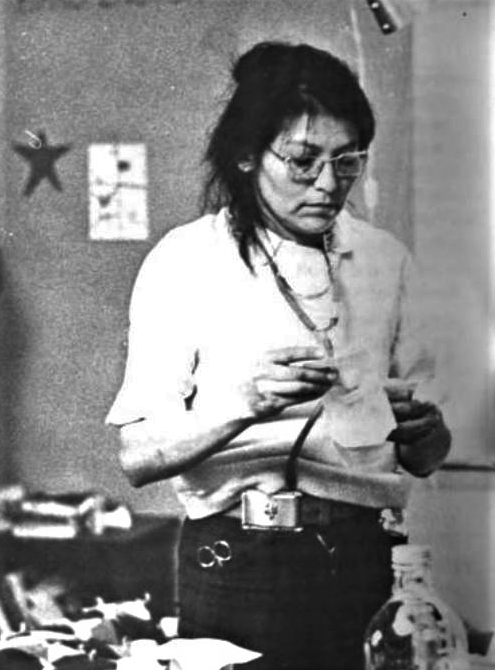

[Added note: Witt was also a founding member of the National Indian Youth Council in 1961, the first “Red Power” organization in the US or Canada. The photos above appeared in the original published version of Witt’s article, but the captions below them have been added. – M. Gouldhawke]

Also

The Last Indian War, by Janet McCloud (1966)

Is the Trend Changing?, by Laura McCloud (1969)

The Six Nation Iroquois Confederacy stands in support of our brothers at Wounded Knee (1973)

Wounded Knee: The Longest War 1890-1973, from Black Flag (1974)

Anna Mae Pictou Aquash in her words (1976)

Indian Activist Killed: Body Found on Pine Ridge, by Candy Hamilton (1976)

Anna Mae Lived and Died For All of Us, by the Boston Indian Council (1976)

Repression on Pine Ridge, by the Amherst Native American Solidarity Committee (1976)

Chronology of Oppression at Pine Ridge, from Victims of Progress (1977)

Excerpts from Leonard Peltier’s Trial Statements with Regard to Anna Mae Pictou Aquash (1977)

The Life and Death of Anna Mae Aquash, by Johanna Brand (1978)

Review of ‘The Life and Death of Anna Mae Aquash’, by Akwesasne Notes (1978)

Anna Mae Aquash, Indian Warrior, by Susan Van Gelder (1979)

Indian Activist’s Bold Life on Film, by John Tuvo (1980)

Poem for Nana, by June Jordan (1980)

Lakota Woman, by Mary Brave Bird and Richard Erdoes (1990)

Pine Ridge warrior treated as ‘just another dead Indian’, by Richard Wagamese (1990)

Leonard Peltier Regarding the Anna Mae Pictou Aquash Investigation (1999-2007)

A Report on the Case of Anna Mae Pictou Aquash, by Zig-Zag (2004)

Feds to re-examine Pine Ridge cases, by Kristi Eaton (2012)

Anna Mae Pictou Aquash: Warrior and Community Organizer, by M.Gouldhawke (2022)

Native Youth Movement Vancouver women show support for Anna Mae Pictou Aquash, Leonard Peltier and John Graham outside the Supreme Court in Vancouver, March 1, 2004

Documentary about the re-occupation of Wounded Knee 1973 and AIM