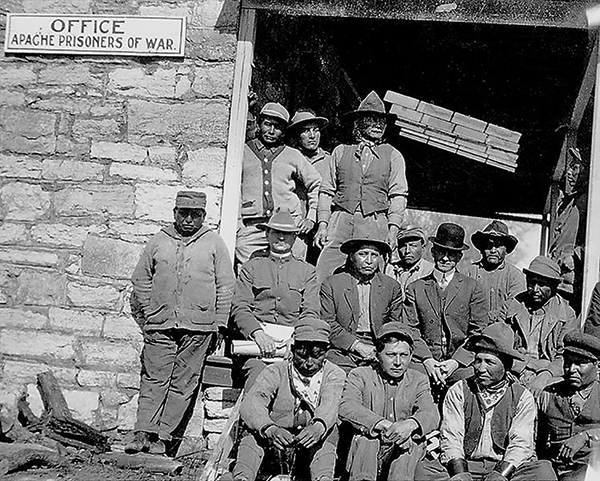

Fort Sill, Oklahoma, 1914

Table of Contents

- Anarchists and the Wild West, by Franklin Rosemont (1986)

- The Indians, from The Alarm (1884)

Anarchists and the Wild West

By Franklin Rosemont, from the Haymarket Scrapbook (1986)

“Eight of the Chicago anarchists were found guilty of murder August 20, seven to be hanged, and one imprisoned for life. The hostile Apaches, including Geronimo, surrendered to General Miles, September 4, on Skeleton Canyon, about sixty-five miles southeast of Fort Bowie, Arizona.” – Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, November 1886

The 1880s, which saw the emergence of a vital working class anarchist movement in America’s eastern and midwestern centers, also witnessed the triumph of “Law’n’Order” in the Far West.

Mere coincidence of chronology, as headlines of the decade announced the deaths of such already-legendary gunmen as Billy the Kid, Johnny Ringo, and Doc Holiday — this last died in his bed just three days before the Chicago Martyrs went to the gallows — made it all the easier for the advance guard of yellow journalism, the proprietors of wax museums and other sensation-mongering upholders of official middle-class morality to dishonestly lump together anarchists and outlaws in an amorphous amalgam of “bad guys.”

More than a year before Haymarket, Prof. Richard T. Ely, distinguished head of the Department of Political Economy at Johns Hopkins University, had set the tone for this type of malicious misrepresentation in his article, “Recent American Socialism”:

“If it were known that one thousand men, like the notorious train robbers, the James’ boys, were in small groups scattered over the United States, would not every conservative and peace-loving householder be filled with alarm, and reasonably so? Yet here [he is discussing anarchists and the IWPA -Rosemont] we have more than ten times that number educated to think robbery, arson, and murder justifiable, nay, even righteous…”

The paragraph containing these lines was reprinted “without the change of a word” in Ely’s influential study, The Labor Movement in the United States (1886). The book adds a footnote suggesting that “there has already been a partial realization of the fears” expressed in the article, and referring specifically to the “Chicago massacre.”

During the Haymarket trial, the prosecution helped promote the same confusion, as when Assistant State Attorney Walker spoke of Adolph Fischer “traveling in the streets of Chicago with an armament [a knife] worse than any Western outlaw.”

In truth, the anarchists who were striving to build a new society free of exploitation and autocracy, had as little in common with the West’s homicidal maniacs and quick-on-the-draw card-sharps as they had with politicians and police. Sensationalist focus on “outlaws,” moreover, served to deflect attention from the frontier’s own labor radicals, many of whom were in touch with the Chicago anarchists.

In 1885, a Christian missionary was quoted as saying that “You can hardly find a group of ranch-men or miners from Colorado to the Pacific, who will not have on their tongue’s end… the infidel ribaldry of Robert lngersoll [and] the socialistic theories of Karl Marx.”1

The real-life cowboy radical was never allowed to enter popular mythology, but the purely fictional anarchist-as-western-desperado stuck around for quite a while. As late as 1904, at the St. Louis Exposition, portraits of the Haymarket Eight were included in a “gallery of notorious criminals,” along with “highwaymen, murderers, robbers” and other assorted cutthroats and crooks.2

The decade 1880-1890 also saw another and far more resounding phase of the “taming of the West” — the definitive military “pacification” (which generally meant extermination) of the Native American population. Between the surrender of Sitting Bull in 1883 and the massacre at Wounded Knee seven years later occurred the last great Indian uprising: the valiant campaign of the Chiricahua Apaches in the Southwest, led by Geronimo. For eighteen months in 1885-86, thirty-five Apache men and eight boys, with 101 women and children to care for, outfought and outwitted 5,000 U.S. army troops and countless armed civilians. For most of 1886, Apaches and anarchists were almost equivalent bugaboos in American newspapers and pictorial weeklies. Many an editor and not a few cartoonists and wits alluded to outbreaks of “savagery” in Arizona and Chicago.

If the anarchists had little or no interest in western hoodlums, they tended to be passionately sympathetic to the Indians, as the editorial below, from The Alarm, amply testifies. Though unsigned, it was probably written by the editor-in-chief, Albert R. Parsons, and in any case can be taken as representative of his views. Its hostility to the government and its solidarity with the native peoples contrast vividly with the racist/chauvinist policies of most American newspapers then and now. Such radical views, however, were in line with long-established tradition in the U.S. workers movement.

As far back as Andrew Jackson’s notorious “Indian Removal” horror of the 1830s, the best-known spokesperson for American labor, George Henry Evans, editor of the movement’s most influential paper, The Working Man’s Advocate, affirmed that the states had “no more right to jurisdiction over the territory of the Cherokees than we have to be King of France.”3

Nearly fifty years later Wendell Phillips, the celebrated abolitionist who, after 1865, gave his energies to the cause of radical labor (Karl Marx proudly claimed him as a member of the First International), devoted one of his last pamphlets to denouncing “the system of injustice, oppression and robbery which the Government calls its ‘Indian policy.'”4

Albert Parsons referred to America’s genocidal war against Indians in a sketch of the history of American capitalism in his posthumously published Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Scientific Basis (Chicago, 1887). Other Chicago anarchists were also interested in the “Indian Question.” Lucy Parsons, herself of Native American descent, took up the subject in her lectures. Adolph Fischer, in a brief autobiography published in the weekly Knights of Labor in Chicago, turned an anecdote about the Oglala Sioux chief Red Cloud into a parable of capitalist exploitation. Most interesting of all, August Spies actually lived for several months with the Chippewas in Canada.5

Significantly, Spies in his Autobiography cited, as one of three works that influenced him most, Lewis Henry Morgan’s Ancient Society (1877), a pioneering and revolutionary anthropological study largely concerned with the Iroquois and other native peoples. Widely hailed a generation later as one of America’s greatest contributions to socialist thought, this book was not well known in the 1880s.

Doubtless Spies, like such European radicals as Marx, Engels and Kropotkin, admired Morgan’s discussions of the primal peoples’ non-governmental (that is, anarchist) and communist societies. Morgan’s conclusion, that future society would entail “a revival, in higher plane, of the liberty, equality and fraternity” enjoyed by “primitive” peoples, became a cornerstone of communist theory. Perhaps it also sheds light on the Chicago anarchists’ solidarity with their Native American allies in the long and bitter struggle against Capitalism and the State.

Notes

- Rev. E.P. Goodwin, cited in David Brion Davis, The Fear of Conspiracy (Ithaca, 1971)

2. Henry David, The History of the Haymarket Affair (New York, 1958)

3. New York Sentinel, March 19, 1832

4. Quoted in Robert Winston Mardock, The Reformers and the American Indian (Columbia, Mo. 1971), 179

5. Paul Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy (Princeton, 1984), 121

[Note: The editorial republished below, The Indians, from the Chicago anarchist newspaper, The Alarm, although arguing for Indigenous autonomy, also contains racist tropes of the ‘noble savage’ and ‘vanishing Indian,’ ideas which the co-editor of the Haymarket Scrapbook and writer, Franklin Rosemont, does not challenge in his own article, Anarchists and the Wild West. -Ed.]

The Indians

From ‘The Alarm’, Chicago November 8, 1884

Hiram Price, commissioner of Indian Affairs, has made his annual report to the secretary of the interior. The commissioner says that more Indians are living in houses and fewer in teepees than a year ago; more are cultivating the soil and fewer following the chase, and there are more in the mechanical shops, and several hundred and more Indian children in the schools. In the near future it is fair to presume that the Indian will be able to care for himself, and be no longer a burden on the government.

“With regard to the cost of the Indian service, the commissioner says: The Indians actually get, of the money appropriated to feed and clothe them, only about seven dollars per annum per capita, or a fraction less than two cents a day for each Indian. The appropriation is too small, if it is expected to transform the Indians into peaceable, industrious and self-supporting citizens in any reasonable time. Among the items for which more liberal appropriations should be made is for pay of police, pay of additional farmers, and pay of the officers who compose the courts of Indian offenses. More liberality in paying Indian agents, and assisting such Indians as show a disposition to help themselves, would be true economy.”

The commissioner says the needs of the Indians require that the Indian appropriation bill be passed early in the Congress session. The misfortunes of the Piegan, Blackfeet and other Indians, he says, are due to the disappearance of game, and their inability to support themselves for the present by agriculture. They will have to depend almost wholly on the government for food for several years. These Indians, with proper assistance, will in a few years own teams and have land under cultivation, which, with a few cattle, will be sufficient to make most of them independent.

What a commentary the above report is upon our boasted civilization. What a jargon of meaningless assertions. The Indian has been “civilized” out of existence and exterminated from the continent by the demon of “personal property.” Originally a docile race, full of pride, spirit, kindness and honor, they were betrayed, then kidnapped and sold into slavery by the early settlers of the Atlantic coast. Their lands appropriated by “law,” the surveyor’s chain reaching from ocean to ocean, driven from the soil, disinherited, robbed and murdered by the piracy of capitalism, this once noble but now degraded, debauched and almost extinct race have become the “national wards” of their profit-mongering civilizers. Under the aegis of “mine and thine,” barbarism became so cruelly refined that man prospers best and only when he exterminates his fellow man.

Left to themselves, left to the exercise of free will and personal liberty — anarchy — the red man would be alive and prospering, dwelling in peace and fellowship with his Caucasian brothers. But “personal ownership'” requires masters and slaves, and the Indian through a ceaseless struggle of more than three centuries has always preferred death to the latter.

Also

A Martyr, from The Alarm (1885)

Law vs Liberty, by Albert Parsons (1887)

The Philosophy of Anarchism, by Albert Parsons (1887)

The Haymarket Martyrs, by Lucy E. Parsons (1926)

The Haymarket Tragedy, by Paul Avrich (1984)

May Day and Colonialism, by K. C. Sinclair (2025)

Settler Colonial Myths (on the vanishing Indian trope)

Anarchism & Indigenous Peoples