Published in Mother Earth, February 1915

At this most earnest time, when the whole of society seems to be disrupted, we also want to raise our voice which has as much right to be heard as that of the other parties. For it was indeed we who have ever been the only ones who opposed militarism under the motto, “Not a single man and not a single penny for militarism.” All the other parties, from the clerical to the Social Democrats, have always been in favor of militarism. They have proved it again and again by voting for the military budgets, thus enabling the governments to carry on war, because without money no soldiers are to be had.

For twenty-five years we have been propagating the only practical means to make war impossible: the proclamation of the General Strike in case of war, and the International Boycott of the powers at war.

The proletariat alone, or the producing workers, have it in their power to stop or to hinder war in a practical manner. Shortly before the threatened war, the International Socialist Bureau gathered in session at Brussels. That was the appropriate moment for a practical resolution, namely, to answer the order for mobilization with a general strike.

Undoubtedly the leaders in the different countries would have been arrested, perhaps executed. That is possible; but in such a case they would have died on the field of honor, and a grateful humanity would have remembered them as benefactors, rather than if they had fallen on the bloody field of war. There is no choice; either one has a principle, or none. If we have a principle we must serve it with loyalty, and die for it if necessary; otherwise we have no principle. Many would have been sacrificed, but in any case not as many as will be demanded by the war. And those who would have been sacrificed would have died in a noble, beautiful cause, and not to further the power of the capitalist class. And if it is objected that the party was too weak, then we ask, “How do we know that? Have we ever tried it?” If not, then an attempt should have been made.

Every revolution in the history of the past was initiated, not by the majorities, but by the minorities; but unfortunately it has been proven true what Schiller once said, “Our century gave birth to a great epoch, but the great moment found a petty generation.”

In Brussels they delivered themselves of beautiful, brilliant speeches; but what was necessary were not samples of oratory but deeds. Lassale very truly said that the princes are served better than the people: the servants of the princes are not orators like the servants of the people, but practical men who know how to act. Quite true; and therefore in decisive moments the people talk and do not act. The Brussels Congress could have done something else if they lacked the courage for militant action. Instead of brilliant talks, they could have issued an explanation to be read in the different parliaments of the various countries when the demand for war appropriations was made. That explanation should have read as follows:

“We, the Social Democrats, declare that we have not the least responsibility for the misdeeds of the governments, and we hereby announce that we do not want to become participants in the manslaughter of war. They, the governments, have directed the ship of state into a swamp, and they will have to pull it out again without our assistance; and we therefore declare ourselves against the war appropriations and resign our commission as representatives of the people to clear ourselves from all criminal responsibility.”

I ask what effect would such an attitude have had upon the people? One hundred and twelve vacant places in the German Parliament, 102 vacant places in the French Chambers, and similarly in Austria, Belgium, Holland, England — the effect would have been tremendous. They would have proved that they are men who could be relied upon.

The Italian Social Democratic Party acted much better. They informed the government that they would, in case of a war with Germany and Austria, proclaim a revolution. This argument has to a great extent helped to keep Italy neutral. Even the attitude of the Russian Social Democracy was more courageous than that of the Germans: the representatives protested against the war, and left the assembly hall. They did not want to vote for the government war budget, as did the German Social Democracy, which made common cause with the Kaiser. A party so powerful as the German Social Democracy, with four and one-half million votes, knew nothing better to do than to offer voluntarily its services to the government, without having the least influence upon the situation.

The national idea has everywhere suppressed internationalism, and thus the latter has everywhere suffered defeat. Here, too, it holds good: Scratch internationalism, and you find nationalism underneath. Must we therefore remain passive, weep and helplessly wring our hands? On the contrary, now is the best time for a fruitful propaganda, for the ears of the masses are open to listen to our ideas. Twelve million women have voiced their protest to the Ambassador and to the English Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sir Edward Grey. That is a good beginning, and it should continue. If the twelve million women should throw themselves between the fighting armies, what would be the result? Wouldn’t the further continuation of the war become impossible? What would be the effect if the transport workers, the railroad and coal workers should combine to make the war impossible, as they combined in Great Britain to secure higher wages! These three industries could, if they would, make an end to the gigantic crime of human slaughter.

Indeed, there is much to be done. Our voices as anti-militarists, as Anarchists and free thinkers must be raised much louder and more powerfully in all the countries where burns the torch of the war, and also where the torch is still to be lit.

Instead of “Not a man and not a penny for militarism” we see the last man and the last penny taken from us, and we meekly submit. We lack the courage to fight for our own interest, but we have enough of it to protect the coffers of the capitalists. How long yet?

In Amsterdam we found it necessary, in these ambiguous days, to make clear our position, and to present to the world the following manifesto:

“In view of the declared European war — the result of capitalism, made possible by militarism, which sets the people of Europe against each other in armed camps — this gathering energetically protests against the horrible human slaughter that defies all culture and humanity, and also protests emphatically against international Christianity, as well as the international Social Democracy, both of which misuse their influence with the people to cultivate national prejudices and antagonisms.

In view of the circumstance that each day might see the invasion of Holland by a foreign army,

and that the wage worker has no quarrel with the workers of other nations,

and that he has no interest in the defense of arbitrary boundary lines, nor in the preservation of ruling dynasties or of any existing regime,

and that he is doomed to a miserable existence and poverty under any and all flags and governments,

and that under no government will he enjoy greater rights and well-being, than he has the power and courage to take;

in further consideration that the defense of boundary lines involves greater misery and destruction than no defense, and that demonstrative refusal to defend would probably result in a more powerful inspiration toward peace;

that in any case the insignificant material possessions and the petty political liberties which the Holland worker enjoys are not worth the shedding of human blood,

and that under a different government the struggle of the proletariat, even if possibly made more difficult, must at the same time also be furthered, and in no case hindered,

and considering, finally, that to defend boundary lines, under whatever pretext, would henceforth preclude and make impossible agitation against any form of militarism,

and that the struggle against militarism is of the utmost importance, because militarism, as an organized power, is the strongest weapon in the hands of the bourgeoisie.

This gathering declares itself ready to continue its struggle against every economic and political oppression, and energetically to further the cause of liberty and well being with the old tried methods, but protests emphatically against the spilling of human blood in defense of nationality, by leaving each one free to act according to circumstance.

DOWN WITH NATIONAL HATRED!

AWAY WITH BOUNDARY LINES!

DOWN WITH WAR!

LONG LIVE THE INTERNATIONAL BROTHERHOOD OF WORKERS!”

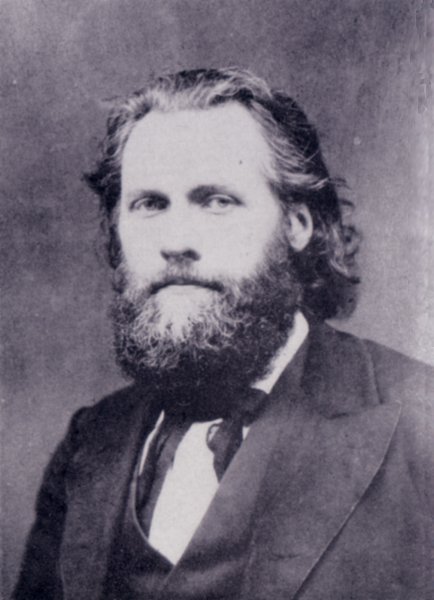

F. DOMELA NIEUVENHUIS

Letter published in Mother Earth, February 1915

6 Argyle Place,

Carlton, Victoria, Australia,

November 12th, 1914

Dear Comrade: I was pleased to hear from you. I like your clear, fearless, uncompromising articles on the war. Your answer to Comrade Kropotkin is honest.

We are either Internationalist Revolutionalists or Authoritarians. To face both ways is impossible. I regret to think that after all these years, having accepted Kropotkin as teacher and guide, he should so disappoint us. I feel oppressed.

We cannot join the selfish brutes who exploit us, who make life a hell in time of peace; who maim and kill us without the least compunction, when we in any way interfere with their beastly existence. Where is the Country and Liberty we are to defend? Echo answers, “Where?” The rulers are brutes, whether English, French, German, Russian or Belgian.

War without compromise against these oppressors! How we would welcome death in defense of a Free Country! But, alas! there is none. So all or nothing! No weakness! Long live Anarchy!

With kindest regards to you, true comrade,

J.W. FLEMING

Also

What does the refusal of military service mean?, by Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis (1893)

Social Democratic and Anarchist Antimilitarism, by Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis (1908)