By Mike Gouldhawke (âpihtawikosisân / Métis-Cree)

Revised October 23, 2022, originally published October 24, 2021

In 1611, English sea captain Henry Hudson suffered a mutiny by his crew and was abandoned and cast adrift in the North American bay that colonial officials named in his honour.

Despite later searches, Hudson’s corpse was never recovered by his countrymen. We could even presume that it was consumed by members of the various animal nations, large or small, that share territory with the Cree and Inuit peoples of the region.

Hudson, the so-called captain and explorer, in actuality got lost one last time, deposed by his own people and then decomposed by the life forms who discovered his carcass.

His name, however, would forever be tied to the colonization of North America and the formation of the capitalist nation-state of Canada, not just with regard to certain bodies of water, but also with the Hudson’s Bay Company, which was granted Indigenous land by way of a Royal Charter.

A charter that was itself derived from the Divine Right of the King, who was supposedly God’s colonial representative on Earth, not just in England.

Ancients

A couple of centuries after Hudson was betrayed by his crew, the exiled German communist Karl Marx made use of the British Museum’s library in writing his book, Capital Volume 1.

In his preface, Marx invoked the “malignant” spirits of revenge, the Furies of ancient Greece, tied to mythical stories of murder in the family.

He used the passion of the Furies as a metaphor for the “private interest” of entities such as the Church in his own time.

Marx also resurrected his theme of the dead dominating the living. This time weaving it together with mention of the Greek myth of Medusa, known for her hair of serpents, capable of turning a living being into inanimate stone, and her slayer Perseus, known for chopping off her head and turning it into a weapon that could be used by whoever held it.

But Marx inverted the use of Perseus’ magic cap of invisibility, writing that while Perseus wore the cap so that the monsters he hunted down wouldn’t be able to see him, “we draw the magic cap down over our own eyes and ears so as to deny that there are any monsters,” by which he meant the horrors of capitalism.

We should not deceive ourselves, suggested Marx, because “the present society is no solid crystal, but an organism capable of change, and constantly engaged in a process of change.”

He compared the study of capitalism to the study of biology, the commodity to the cell, and the power of abstraction to that of the microscope used to study anatomy. This was all before he had even gotten into the real meat of his book, where he would dive deeper into matters of the body, life, death, mystification, revelation, metamorphosis and monsters.

Marx’s method was that of dissecting out the compositional units of society and then stitching them together again, in order to understand the whole body. But his method also included the literary, metaphorical and allegorical, not just stuffy technical scholarship.

Beasts

Present-day scholars like William Clare Roberts, Mark Neocleous and David McNally in their writing have shown an appreciation for Marx’s use of monster metaphors, as for example when Marx wrote of capital’s “werewolf-like hunger for surplus labour,” and when he described capital as “dead labour which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks.”

Roberts, in his book Marx’s Inferno, points to Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s invocation of the vampire as one of several potential influences on Marx.

However, for my part, I’d like to note that before Proudhon had mentioned the vampire in his book, The System of Economic Contradictions, he had already deployed a different kind of monster in another book.

In What is Property, Proudhon had described “the right of increase” as being “conferred in a very mysterious and supernatural manner,” insofar as an object, as property, is consecrated and imbued with an inherent moral quality.

Coincidentally or not, this calls to mind Marx’s later categories in Capital of the socially objective fetish character of the commodity which necessarily leads to commodity fetishism, a form of consciousness.

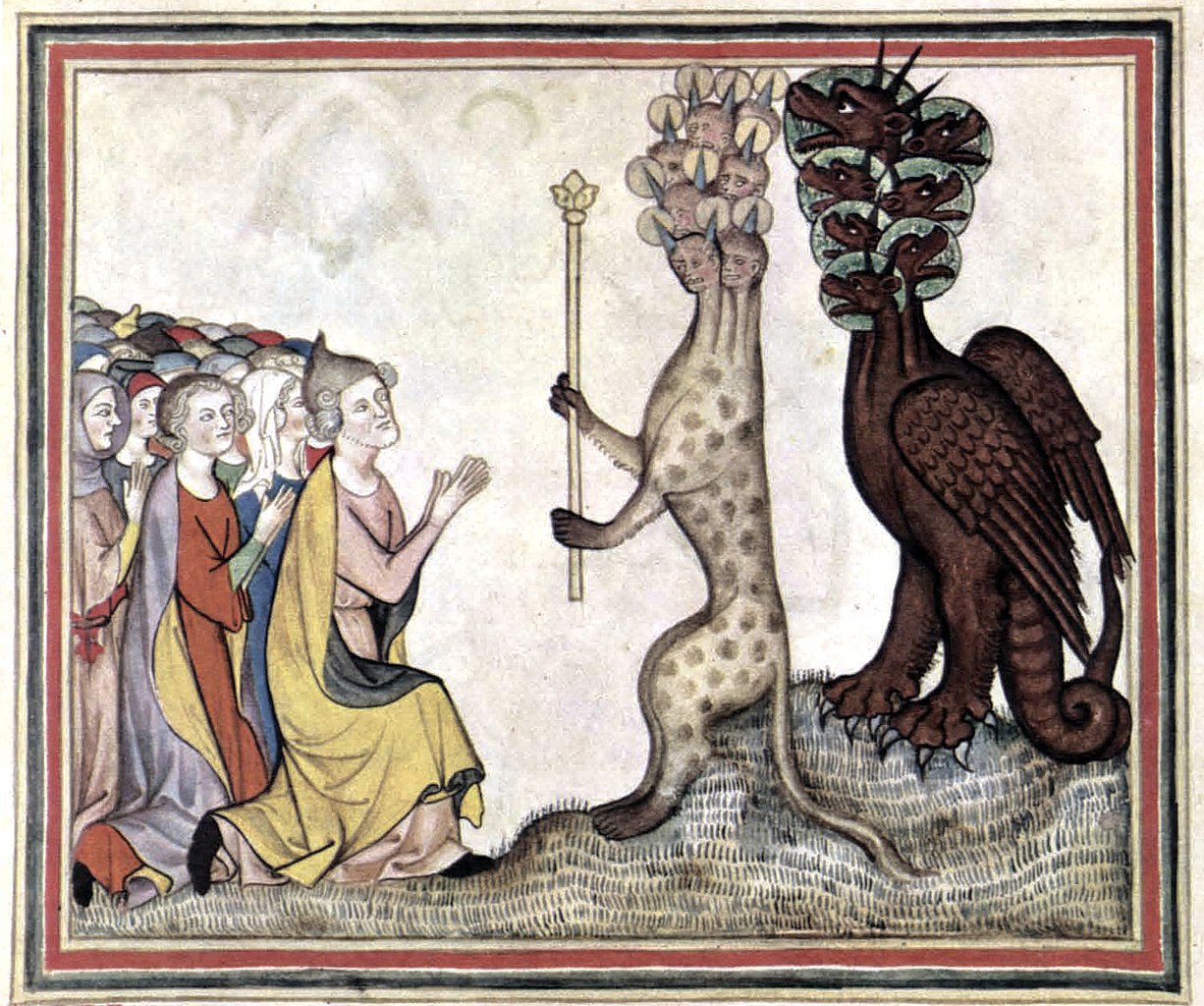

Proudhon, in What is Property, had written that to understand the right of property would be like learning “the name of the beast in the Apocalypse — a name in which is hidden the complete explanation of the whole mystery of this beast.”

Marx, in his later chapter on money, would use a quote from the Book of Revelation, “that no man might buy or sell, save that he had the mark, or the name of the beast, or the number of his name.”

Proudhon, on the other hand, had compared “the right of increase” to the taenia genus of various tapeworm species, a parasite which he compared to the many-headed beast of the Apocalypse.

He depicted this tapeworm as a serpent with coils and a head with many suckers, a beast “hidden from the sword,” that would take more than just courage to defeat. As Proudhon told us, legend had it that only a proletarian armed with a magic wand could kill this beast.

This earlier monster deployed by Proudhon can be compared not just to the later use of Medusa and Perseus by Marx in his preface to Capital, but also his deployment of blood-sucking vampires and werewolves in the main body of his text.

Furthermore, Proudhon’s tapeworm, unlike the later vampire, doesn’t just represent a fictional creature or metaphor, but also an actual earthly parasite, transferred to humans from animals through their consumption, the sustenance of life by way of death.

This particular parasite doesn’t just attack from outside, but also from within the body itself. Consequently, it implicitly, if indirectly, challenges the Christian concept of human dominion over other life forms, of our supposed separation and fortification as individuals from the world we live in. Because of this, the animal may also be regarded as evil by the human-centric true believer.

Reduction

Mark Neocleous has already written an interesting investigation of Marx’s use of the vampire metaphor, so instead, here I’d like to also look at Marx’s deployment of more mundane beasts, his reduction of human beings to other animals, and his analysis of the practical reduction of living beings to one of their characteristics or components.

Marx, in his early manuscripts of 1844, wrote that “external labor, labor in which man alienates himself, is a labor of self-sacrifice, of mortification.”

The worker, Marx wrote, only feels free and alive when not at work, “in his animal functions – eating, drinking, procreating, or at most in his dwelling and in dressing-up, etc.”

In contrast, when at work and using their conscious human capacities, the worker no longer feels like they are “anything but an animal.”

“What is animal becomes human,” wrote Marx, “and what is human becomes animal.”

This somewhat disdainful view of animals may reflect a residual of Judeo-Christian notions and norms of human dominion, something that permeates Western society as a whole, not just the true believer, and which is alien to the traditional spiritual cosmology of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Marx admitted that bees, beavers, and ants build homes for themselves, but he also claimed that “an animal only produces what it immediately needs for itself or its young.”

An animal “produces one-sidedly, whilst man produces universally,” Marx explained.

However, putting aside for a moment the differences in consciousness between humans and other animals, we can recognize in our time that Marx was not quite right here, that the beaver, for example, is a keystone species that produces more generally, if not universally, providing habitat for other species, even if unintentionally.

Marx’s use of animal analogies also continued in Capital.

In German, the word Marx used for the value of commodities, which he described as coagulated abstract labour, also translates as “jelly,” something discussed by scholar Keston Sutherland.

The process of making gelatine, of course, involves the extraction of material from various animal body parts and their reduction to an indistinct, colourless and flavourless material, which can then be further processed for a variety of uses, making it an apt metaphor for the value of commodities, which are all produced by the consumption of labour-power, regardless of the kind of labour performed.

Equality

In the first edition of Capital, Marx characterized the general equivalent form of value (which later transitions to the money-form) in terms of the various species of animals.

“It is as if alongside and external to lions, tigers, rabbits, and all other actual animals, there existed also in addition the animal, the individual incarnation of the entire animal kingdom.”

Later, Marx quoted colonial official Edward Gibbon Wakefield on the disposability and replaceability of overworked human beings, those who “die off with strange rapidity,” but whose positions are “instantly filled” without altering the conditions of production.

Marx also mentioned the violent displacement of workers from the land to make way for sheep pasture for landlords, including its colonial dimension, where the “the Irishman, banished by the sheep and the ox, re-appears on the other side of the ocean as a Fenian,” in other words as a nationalist republican.

In this very limited sense then, workers under capitalism, while formally free, are also not entirely unlike other animals, insofar as they are treated as a mass of indistinct machines, as material to be used for other purposes, or as entirely disposable, as worthless to themselves.

In writing about the value of the commodity as manifested in its equality with other commodities, Marx compared it to the “sheep-like nature of the Christian,” which is shown in “his resemblance to the Lamb of God.”

Here, Marx was perhaps returning to his theme of spiritual self-sacrifice through labour that is commanded by others, and of homogeneity amidst hierarchy, as first highlighted in his 1844 manuscripts.

Equality as fungibility, in service of inequality.

Ghosts

In describing the social objectivity of commodities as values, Marx used within the same paragraph increasingly solidifying metaphors of the ghostly, the congealed and the crystallized, as a way of contrasting the living labour that produces commodities to its objectification and representation in the product of labour.

The ghost, as a symbol, doesn’t just stand for the intangible, but also the afterlife, the human spirit and its ongoing possession of the material world beyond death. It also stands for reflection, the representation of one thing, the living, in another form, the dead as apparition. Even if it hovers rather than standing on physical legs.

The value of the commodity is purely social and doesn’t contain an atom of matter, Marx stressed. Nonetheless, the commodity has a dual form, value and use-value. The commodity itself is not labour, but a reflection of labour, which itself has a dual character corresponding to the dual form of the commodity.

Workers, through their living labour, raise dead labours from their petrified commodity form as means of production and give them power as things that can continue to antagonize the living.

As David McNally writes, “in a perverse dialectical inversion, the very powers of labour that re-animate the dead also deaden the living, reifying them, reducing them to a zombie-state.”

As Marx wrote, “a commodity appears at first sight an extremely obvious, trivial thing, but its analysis brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.”

Yet, “the magic and necromancy that surrounds the products of labour on the basis of commodity production” vanishes as soon as we come to other forms of production, said Marx. And not just when we look at past forms of production, but also when we think of a future one, where the means of production would be held communally.

Possession

Despite their different forms of appearance, each commodity, Marx said, recognizes in the other “a splendid kindred soul, the soul of value.”

“A born leveller and cynic,” each commodity is “always ready to exchange not only soul, but body, with each and every other commodity,” Marx wrote, alluding to the delusions of Cervantes’ character Don Quixote who mistakes the ugly Maritornes for a more beautiful woman.

Later in Capital, Marx quoted the quintessential colonizer Christopher Columbus as having written that the owner of money is master of all they may desire, and that “Gold can even enable souls to enter Paradise.”

“Everything, commodity or not,” wrote Marx, “is convertible into money,” since the form of money is indifferent to its particular origins in other commodities, or labour, or natural wealth.

The capitalist as a person is only capital personified. The soul of the capitalist “is the soul of capital.”

With the separation of workers from the land under capitalism, “a new social soul” enters the body of the commodity, as it comes to form a part of the capital of the manufacturer.

“The means of production and subsistence, while they remain the property of the immediate producer, are not capital,” Marx explained. “They only become capital under circumstances in which they serve at the same time as means of exploitation of, and domination over, the worker.”

These circumstances being where divisions of class, labour and property are welded together in a new form and given a new spirit driven toward endless accumulation.

Marx continuously drew his reader’s attention to the separations and inversions perpetuated under capitalism, where means of production employ workers, rather than vice-versa, and commodities seem to have inherent social characteristics.

A mundane table, as a commodity, is inverted in its relation to other commodities, and “evolves out of its wooden brain grotesque ideas, far more wonderful than if it were to begin dancing of its own free will.”

Marx followed his depiction of a possessed table with an imagining of what commodities would say about themselves if they could speak, which would be that their value is what belongs to them as objects, not their use-value, which is the concern of people.

Immediately following this, at the beginning of the next chapter, Marx reminded his reader that commodities are not actually alive and can’t take themselves to market or hang prices on themselves, so we have to also consider their “possessors,” the owners of commodities.

Consumption

In his early critique of Proudhon, Marx wrote of the consumption of the worker by capitalist labour, which leaves only a human shell behind.

“Time is everything, man is nothing,” he explained. The worker is reduced to “time’s carcass.”

Later, in Capital, Marx wrote that the capitalist incorporates living labour into the “lifeless objectivity” of the means of production.

“The capitalist simultaneously transforms value, i.e. past labour in its objectified and lifeless form, into capital, value which can perform its own valorization process, an animated monster which begins to ‘work’, ‘as if its body were by love possessed,'” Marx wrote, in a reference to Goethe’s story of Faust and a convulsing rat, poisoned by a cook.

In his previous Grundrisse notebooks, Marx had also used the Faust reference, but in that case, capital was said to absorb “labour into itself,” so that “what was the living worker’s activity becomes the activity of the machine.”

Marx went on to write in Capital that the working day under capitalism steals from the worker “the time required for the consumption of fresh air and sunlight.”

The extension of the working day “usurps the time for growth, development and healthy maintenance of the body.”

Here we can see why Marx referred to capital as vampire-like. Not just because it consumes labour-power, but because of how it does so, and that it does so to the extent of interfering with human and social metabolism, the maintenance of life, and the division of day and night.

For the capitalist, “production is also immediately consumption,” Marx wrote in his Introduction of 1857. Consumption, in this case, of both raw materials and “life forces,” the working capacity of the worker.

In consuming food, the human being produces their own body. However, “production not only supplies a material for the need, but it also supplies a need for the material.”

In order to live, people must eat, just as in order to produce, capitalists must purchase and consume means of production, and workers must sell their labour-power in order to earn money to buy food and shelter.

In Capital, Marx remarked on the class inequality of living conditions that was revealed by a Royal Commission, whose findings turned the stomach of the British public. A report in which it was shown that workers were eating bread containing “a certain quantity of human perspiration mixed with the discharge of abscesses, cobwebs, dead cockroaches and putrid German yeast, not to mention alum, sand and other agreeable mineral ingredients.”

The consumption necessary for life cannot escape labour, social metabolism, or death. But what is always in question is under what conditions, under what system will such labour and metabolism take place?

Particular living beings are always broken down and metabolized by other living beings. Humanity must always interact with the material world in order to survive. The real question is how to live well, and to what end? How to destroy the capitalist form of work, which is also destroying the planet?

The conditions of life are not the same for all people under a class-divided society, even if under capitalism, all people are all subject to value and capital.

Cannibals

Marx, in Capital, didn’t shy away from mentioning “the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the indigenous population” of the Americas, or the “conquest and plunder of India, and the conversion of Africa into a preserve for the commercial hunting of blackskins,” as things which he said “characterize the dawn of the era of capitalist production.”

He quoted William Howitt, “a man who specializes in being a Christian,” on the unparalleled barbarities and outrages that Christians had subjected various peoples to “throughout every region of the world.”

However, by the time Marx died in 1883, militant Indigenous resistance to colonialism in North America had not ended, and the United States and Canada had yet to even secure their current territory.

Around this same time, one of my own ancestors, James Settee, an Ininiw (Swampy Cree) teacher and priest, wrote down a story he had heard told to his home community when he was child.

In this story, a great battle between brothers ends when the younger and supposedly weaker brother, the rabbit “Wahpus”, is able to defeat his eldest brother, the powerful northern wind, Keewatin.

Afterwards, another one of the brothers, Wahpun (the East), says he will bring many useful foreign tools westward. Rabbit interjects, warning that while the tools will be useful, Wahpun will also bring with him from across the Atlantic Ocean the “Weedigoo”, who will “consume human flesh.”

From the perspective of Ininiwak (Swampy Cree people), the east is not Asia but Europe, which invades westward, toward the Americas.

In Settee’s account, his community reinterprets the story in an optimistic light. Rabbit will join forces with his brother Shawun (the South), and there will be a global revolution, where Rabbit will remain undefeated.

This story, first published in 1977, almost a hundred years after first being written, wasn’t cited by Powhatan and Lenape writer Jack D. Forbes in his 1978 book, Columbus and Other Cannibals, which popularized the Cree concept and term of the Wetiko.

Forbes didn’t explain why he chose to use this word from another Indigenous people’s language, although Powhatan and Lenape share the Algonquian language family with Cree.

In fact, Forbes cites no one directly in his use of the Cree term, only indirectly referencing a source by way of quoting the Cree singer and organizer Buffy Sainte-Marie, who said that “the whites carry the greed disease… they need to be cured, but they usually don’t mind their disease, or even recognize it, because it’s all they know and their leaders encourage them in it, and many of them are beyond help.”

However, it’s important to also note here, for those unfamiliar, that the Wetiko and the dynamic in question isn’t only foreign or colonial, but also a potential within Indigenous communities themselves, which is to be self-organized against.

The dynamic at hand consists not of the direct consumption of people, but of greed, harm and negative relationality more generally, something Indigenous legal structures have always contended with, before and during colonization, which itself hasn’t ended.

Furthermore, it’s important in our time to not simply associate different ways of thinking with evil, or uncritically adopt capitalist and colonialist versions of mental health, but to be more specific about what exactly is to be considered harmful action or behavior.

Metamorphosis

In Capital, Marx used the Christian metaphor of transubstantiation for the metamorphosis of commodities into money, the change in form “through which the social metabolism is mediated.”

In the actual ritual of transubstantiation, the human flock is thought to consume the blood and flesh of their own Lord, Jesus Christ.

The cannibalism that is considered profane to the Indigenous peoples of the Americas is inverted and considered as sacred to Europeans, who build their society not only by stealing from other peoples but by consuming their own.

For Ininiwak, the story of the Rabbit (Wahpus) might be doubly spiritually significant, because the rabbit is an intelligent survivor in their own right, but also helps human beings survive, both by teaching lessons to people and as a food source to be consumed by people, with respect, rather than through a relation of hierarchy, class exploitation and abuse.

For Euro/American Christians, on the other hand, the needless sacrifice of the innocent Lamb of God is considered a worthy transaction in the salvation of souls, something more important than the actual condition of real lives on Earth.

As Henry Hudson learned the hard way, even relations of respect, when based on hierarchy, can be a form of appearance under which lies relations of betrayal and cannibalism that are scratching to reach the surface.

Tradition

Proudhon, for his part, may have been right about terrible beasts and where they hide, if only to the extent that courage alone is not enough to defeat the monster of capitalist exploitation.

Marx more groundedly advocated for using the power of abstraction, both in analyzing the current system and imagining a different one, “for a change, an association of free people who labour with the means of production held communally.”

If Marx, in Capital at least, had been more concerned with the conditions in the colonies and not just the secret of European capitalism that had been discovered by political economy in the Americas, he might have seen the value in the Indigenous resistance to colonialism and capitalism that persisted in his time and which still continues today.

For Marx, when it came to social revolution, “the tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.”

This very well may be true, insofar as we are talking about the histories internal to particular Euro/American class societies and resistance within them, not resistance to them from the outside, which is to say, from inside the colonies, from colonized peoples resisting colonization.

For Indigenous peoples, on the other hand, tradition, like death, is neither inherently good nor bad, neither a wishful dream nor a nightmare, but instead one part of life, of necessary transformation and interrelationality.

Tradition is not just about the past, but also the future, and can be used dynamically, to build capacity by learning from past mistakes and combining lessons collectively, by synthesizing new traditions, as tools in the struggle against oppression and to maintain an environment capable of sustaining life for future generations.

Perhaps it’s even possible to find some use in combining various traditions, from different regions, like the story of Rabbit and the South joining forces against the North, but without, for all that, different groups having to surrender their identity and autonomy.

Perhaps after capital, another kind of social relation is possible. Respect without hierarchy, and social metabolism, the maintenance of life, without class exploitation and abuse.

Taenia genus of tapeworm

See also:

The Social Interest and its influence on Capital