by M.Gouldhawke (Métis-Cree)

January 26, 2020

(This article is part two of a series on UNDRIP’s adoption in BC. Part one can be found here.)

BC’s recent adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) through Bill 41 was the subject of a major corporate conference at the Vancouver Convention Centre on January 14th, 2020, focused on the expanded business opportunities that have supposedly been unlocked in the Declaration’s wake.

Entitled “UNDRIP 2020 – Finding the Path to Shared Prosperity,” the event’s tickets ran from $316 to $3,000, signaling that a conference about the business potential of Indigenous rights was also something of a business in itself.

“I didn’t realize how big of a conference it was when I was first asked to speak,” Williams Lake Indian Band Chief Willie Sellars told the Williams Lake Tribune. “They had 550 tickets and they sold out and people are clambering to get into it.”

Corporate sponsors included major oil and gas pipeline and energy companies, along with event partner, the First Nations LNG Alliance, the public relations arm of the band councils involved in the Coastal GasLink pipeline which is opposed by hereditary Wet’suwet’en chiefs and their supporters.

A major theme of UNDRIP 2020, it turns out, was the question of consent. What does it mean for one group, a corporation, to ask to enter the territory of another group, an Indigenous people? BC’s government and business community might forgive you for being an ignorant peasant and thinking this should be a simple matter, that “consent” isn’t a very big word and that no obviously means no.

“What the legislation doesn’t do… is it doesn’t create new rights,” said Doug Caul, BC’s deputy minister of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation, during the conference’s opening session. “Indigenous rights are already recognized in the Constitution, under Section 35. There are rights that the courts have consistently upheld.”

“It also doesn’t give Indigenous people the veto,” Caul later added, according to the Business in Vancouver newspaper’s report on the UNDRIP 2020 conference.

“Veto” is in fact a trending topic these days among the BC government, the media and the business community, a way to avoid the word “consent” and its content, to reassure the public that it doesn’t matter if Indigenous communities say “no” to a development project, that the settler majority still rules and the “public interest,” whatever the heck that’s supposed to be, is still superior to the interests of Indigenous peoples.

Deputy minister Caul explained at the UNDRIP 2020 conference that the “free, prior and informed consent” called for in UNDRIP is in fact only about “engaging with Indigenous people about proposed activities in their areas from the beginning, in a deep meaningful way.” So Indigenous peoples’ answer to a question of development isn’t what’s important, just the popping of the magic question itself, and then presumably proceeding with business as usual, without consent.

When asked “who defines consent?” during a question and answer period, Caul said it’s a “process” that First Nations themselves have to go through to decide. But exactly who or what is he referring to when he says “First Nations” here? The actual communities themselves or just the band councils imposed under Canada’s Indian Act? If a community say “no,” why does another group, a band council, get to say “yes?”

Laughing all the way to the bank at the UNDRIP 2020 conference in Vancouver with Doug Caul, BC’s deputy minister of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation

Laughing all the way to the bank at the UNDRIP 2020 conference in Vancouver with Doug Caul, BC’s deputy minister of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation

Are we really meant to believe that consent is not a definitive answer or decision, is not a matter of community self-determination, but just an ambiguous “process” where approval by band councils, whose authority is delegated by Canada, can override a lack of consent on the part of communities and hereditary chiefs? This has in fact been the message put forward in the media recently by Premier John Horgan and industry spokespeople.

Consent isn’t always that complicated of a concept to everyone, so the BC government and corporations have had to dance around the issue rather than address it directly, to instead misdirect a public that is uneducated about the band council system and convince them that band councils are legitimate representatives of Indigenous communities and not just lower branches of the Canadian government, funded by the head office in Ottawa.

“There has to be a mutual understanding of what consent is, and we haven’t done that yet,” UNDRIP 2020 event emcee Mark Podlasly told Business in Vancouver. Government and corporations apparently still have a long way to go to learn that no means no, even if social movements have been trying to make it loud and clear for a while now.

The official UNDRIP 2020 conference magazine, “Rights and Respect,” even republished an article entitled “Myths about Indigenous Consent,” originally published by UBC’s Residential School History and Dialogue Centre and written by Dr. Roshan Danesh. In the article, Danesh writes that while consent is part of Canadian Aboriginal law, “Consent and veto are not the same thing, and consent is not a veto over resource development.”

“First, no rights are absolute,” explains Danesh, “This is true in our Charter, Section 35 of our Constitution, and in the UN Declaration.” He goes on to point out that “Article 46(2) of the UN Declaration makes this explicit in stating how the exercise of rights, including consent, may be limited.”

Article 46 is in fact the final article of the Declaration, the one that settler colonial states like Canada held out for, voting against UNDRIP until it was included. It states that nothing in the Declaration should “dismember or impair, totally or in part, the territorial integrity or political unity of sovereign and independent States,” referring to the settler colonial states like Canada whose fragile claim to sovereignty over Indigenous land is found only in the racist Doctrine of Discovery, the idea that Europeans only had to assert sovereignty over Native land in order to obtain superior rights and title, without Indigenous consent.

Furthermore, Article 46 asserts that Indigenous rights can be limited by the laws of settler colonial governments, stating that “The exercise of the rights set forth in this Declaration shall be subject only to such limitations as are determined by law and in accordance with international human rights obligations… for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and for meeting the just and most compelling requirements of a democratic society.” So once again, Indigenous rights can be restricted to allow space for the superior rights of settlers.

In 2019, Danesh even co-wrote a cynically titled document related to UNDRIP called “Operationalizing Indigenous Consent through Land Planning.” Consent is not framed as agency on the part of Indigenous peoples in this text but instead as a method that government and corporations can use to advance their own projects, to “collaboratively achieve consent, while advancing greater predictability in decision-making.” Consent is already framed as a “yes” yet to be achieved, before discussions have even taken place.

“Consent, like all rights, is not absolute” claims Danesh in a sub-heading of his document. However, this is not actually the case, as some rights are in fact considered absolute and non-derogable in democratic nation-states, such as the right to not be held in slavery (outside of prisons) and the right of sexual consent.

Under Canadian law all sexual activity without consent is a criminal offence, meaning that in this case, consent is an absolute principle in regards to the rights of the individual.

In medical practice, patient consent is a near absolute and can only be abridged in limited cases where consent is not possible and harm is to be prevented to the patient and other people.

Indigenous peoples, though wrongly regarded as wards of the state, are in actual fact competent and fully capable of refusing consent in order to prevent harm to themselves and others, and should be treated as such, not as targets in need of convincing as to why a project should go ahead.

Another sub-heading in Danesh’s paper explains that “Consent is a way of removing uncertainty.” Here a private business interest, economic certainty, is instrumentalized against Indigenous consent, and collaboration is promoted as a means to circumvent potential Aboriginal title litigation in the future.

But collaboration with who? Industry and government’s dirty secret is that they seek to work with band councils, not communities. But band councils are delegated their authority by the Indian Act and Section 91 of the Constitution.

The Supreme Court has confirmed more than once that it is Indigenous peoples as collectives that hold Aboriginal rights and title under Section 35, not band councils. It was Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan hereditary chiefs, not band councils, who brought forward the milestone Delgamuukw-Gisday’wa case decided upon by the Supreme Court in 1997, which determined that Aboriginal title had never been extinguished in BC.

Also featured in the UNDRIP 2020 “Rights and Respect” magazine was Karen Ogen-Toews, Wet’suwet’en band councilor and CEO of the First Nations LNG Alliance, who said, “I see UNDRIP creating more certainty. I’m hoping that investors hear this message. There are mixed messages being told out there. We want them to hear from the Indigenous people that want a better life — and are open for business.”

While the media and corporate interests have engaged in much hand wringing recently about the supposedly undemocratic nature of the hereditary chief system, a Business in Vancouver article on the UNDRIP 2020 conference explained that no ratification vote was actually held for the Coastal GasLink project within the Wet’suwet’en Nation, and that instead only some informal polling was done. So much for democracy.

Anti-treaty blockade in Tla’amin territory, BC, in 2013

Anti-treaty blockade in Tla’amin territory, BC, in 2013

The modern BC Treaty Process seeks to circumvent the problem of community consent by negotiating limitations to Section 35 Aboriginal rights with band councils, who do not even hold such rights in the first place. The Tsawwassen Final Agreement of 2007 under the Process, for instance, modifies and limits Section 35 rights and title, converting territory the band council doesn’t even have jurisdiction over from Crown land held “for Indians” into fee simple private property that can be sold to and bought by corporations and settlers. The agreement also protects Canada from any future lawsuits over Aboriginal title, securing economic certainty for future corporate development.

This is why former Tsawwassen Chief and treaty negotiator Kim Baird was a featured speaker at the UNDRIP 2020 conference, along with Braden Smith, current Chief Administrative Officer for the Tsawwassen First Nation, which has seen major corporate development on its fee simple lands in recent years, including a shipping warehouse for Amazon, a notorious exploiter, and abuser of its workers’ dignity.

However, even the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) has not shied away from deploying racist conceptions of Indigenous peoples rights, as for example when it reaffirmed the Doctrine of Discovery in its Tsilhqot’in decision in 2014, and in its Daniels decision in 2016, when it openly construed the Métis Nation as a historical “threat” to Canada’s westward expansion that required suppressing under the unilateral legal power of Section 91 of the Constitution.

In the SCC’s Haida decision of 2004, it stated that a process of accommodation “does not give Aboriginal groups a veto over what can be done with land pending final proof of the claim.” It went on to explain that “The Aboriginal ‘consent’ spoken of in Delgamuukw is appropriate only in cases of established rights, and then by no means in every case. Rather, what is required is a process of balancing interests, of give and take.”

This false concept of balance, as if Indigenous peoples and Canada were playing on an even field after hundreds of years of colonialism, was also reiterated in the SCC’s Chippewas of the Thames decision as recently as 2017, where it was claimed that “The Chippewas of the Thames are not entitled to a one-sided process, but rather, a cooperative one with a view towards reconciliation. Balance and compromise are inherent in that process (Haida, at para. 50).”

Supreme Court decisions have consistently framed reconciliation as a goal of Section 35 Aboriginal rights, but have just as systematically framed this in a backwards fashion, as a framework that “permits a principled reconciliation of Aboriginal rights with the interests of all Canadians.” (Tsilhqot’in 2014)

In the SCC’s Delgamuukw decision of 1997, Section 35’s purpose was said to be “to reconcile the prior presence of aboriginal peoples with the assertion of Crown sovereignty.” But if Indigenous peoples were here first, shouldn’t it be Canada that needs to reconcile itself with Indigenous sovereignty, not the other way around? And how and why are we supposed to reconcile ourselves with a racist assertion based on the Doctrine of Discovery? It should be Canada that needs to justify its existence and title, not us, especially after centuries of lies, theft and oppression on their part and an equal amount of time on ours trying to come to reasonable agreements with them.

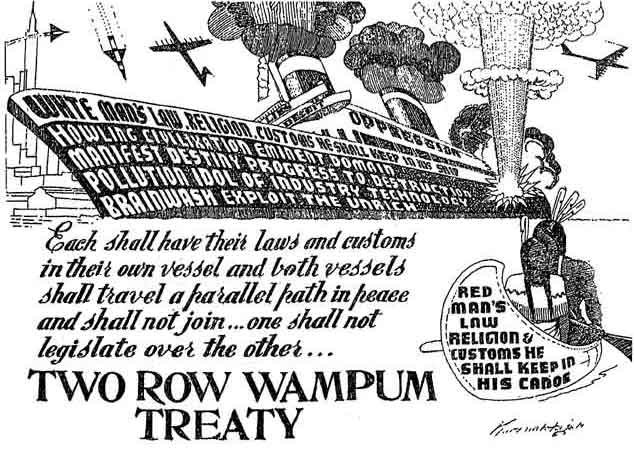

Art by Louis Karoniaktajeh Hall (Mohawk Nation)

Art by Louis Karoniaktajeh Hall (Mohawk Nation)

Jennifer Turner, a special projects director with the corporate public relations group Resource Works and the director for the UNDRIP 2020 conference, recently spoke to CKNW 980 Radio about the conference and called UNDRIP “a very broad and aspirational document.”

“It’s not a legal document in and of itself, it’s not prescriptive, so it describes a destination that we all need to work on and arrive at in Canada,” explained Turner.

Responding to a question about the Coastal GasLink conflict in Wet’suwet’en territory, Turner said it’s “really critical to not in fact make UNDRIP about one specific project.”

“Deeper issues” in regards to an “economic argument”, such as community “pain,” the epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, residential schools and child apprehension are all mobilized by Turner in the interview to justify pushing forward with development projects without consent, such as in the case of Coastal GasLink. Supposed “economic prosperity” forced upon Indigenous people by self-proclaimed “non-Indigenous allies” like Turner is posed as the solution to the Indigenous problem. Colonialism will solve itself if we just step aside. Maybe money is supposed to trickle down somehow, instead of continuously stuffing the pockets of elites.

Turner also pretended to be surprised during the radio interview at the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination’s recent statement that Coastal GasLink and other such projects should not go ahead. With regards to BC’s Bill 41, “it’s really up to BC to decide” what UNDRIP implementation is “going to look like for us,” said Turner, not the United Nations. If BC decides to disregard Indigenous rights and international standards, so it goes.

Wet’suwet’en land defenders have consistently taken the opposite position from Turner here, saying “no” to the man camps that have been constructed to help build the Coastal GasLink pipeline, saying the camps “create the social conditions for an increase of violence against Indigenous women and children.”

At a Vancouver rally in support of the Wet’suwet’en Nation and Unist’ot’en camp back in 2012, Laura Holland of the Wet’suwet’en made clear the link between violence toward the land and the people. “In my lived experience, as a daughter, sister, mother, grandmother and front-line worker,” said Holland, “I have witnessed the violence in connection to the theft of resources and rapes of Wet’suwet’en land, Wet’suwet’en women and Wet’suwet’en children.”

Indigenous rights, title and land defense are a joke to some people (deputy minister Doug Caul, center, at the Association for Mineral Exploration’s 2020 Roundup Conference in Vancouver)

Indigenous rights, title and land defense are a joke to some people (deputy minister Doug Caul, center, at the Association for Mineral Exploration’s 2020 Roundup Conference in Vancouver)

BC deputy minister Doug Caul also spoke about UNDRIP at the recent Association for Mineral Exploration’s 2020 Roundup Conference in Vancouver over the weekend of January 20th-23rd, reassuring the mining industry that not much has changed or will change with BC’s adoption of UNDRIP through Bill 41, because industry already consults with First Nations band councils anyway. “You can’t flip a switch and suddenly try to bring (laws) into harmony,” Caul told the conference, also restating that neither UNDRIP nor Bill 41 give Indigenous peoples a “veto” over particular projects.

BC’s adoption of UNDRIP and the BC Treaty Process are united in that settler governments, band councils and corporations are making agreements to create economic certainty for themselves and negotiate away our rights behind our backs, with no regard for community consent.

While Indigenous incarceration rates continuously skyrocket, reserve communities remain struggling with a lack of clean drinking water and housing, and the urban Indigenous houseless population are targeted for injunctions much as rural land defenders are, the Aboriginal business elite are hamming it up at high-priced conferences and shaking hands with their counterparts in settler governments and corporations, negotiating another solution to the “Indian problem” where profits continue to flow to them at the expense of the rest of us, using the empty rhetoric of “rights” to run cover for their dirty work behind the scenes.

Sources and further reading

Indigenous Law, UNDRIP and Corporate Developement in BC, by M.Gouldhawke

Rights and Respect official UNDRIP 2020 magazine

Tickets for UNDRIP 2020 starting at $316

B.C. mulls potential promise and pitfalls of UNDRIP (Business in Vancouver)

Outlook 2020: First Nations economic reconciliation to continue (Business in Vancouver)

Horgan: Coastal GasLink ‘will be proceeding’ (Business in Vancouver)

UNDRIP: exploring the opportunities (Business in Vancouver)

Unpacking UNDRIP (Business in Vancouver)

No consensus on what constitutes consent in UNDRIP (Business in Vancouver)

Cariboo-Chilcotin area chiefs Alphonse and Sellars to address UNDRIP 2020 (Williams Lake Tribune)

B.C.’s UNDRIP law a big step, but not necessarily a big change for mining (Vancouver Sun)

Billion dollar boom: UNDRIP opens the door to First Nations partnerships (Vancouver Sun)

Update on Bill 41: With DRIPA as Law, What Can We Expect Next?

Editorial: Confronting Myths About Indigenous Consent, by Dr. Roshan Danesh

Operationalizing Indigenous Consent through Land-Use Planning, by Dr. Roshan Danesh

UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination statement regarding Coastal GasLink, etc.

Tsawwassen First Nation Final Agreement under the modern BC Treaty Process (2007)