Intro

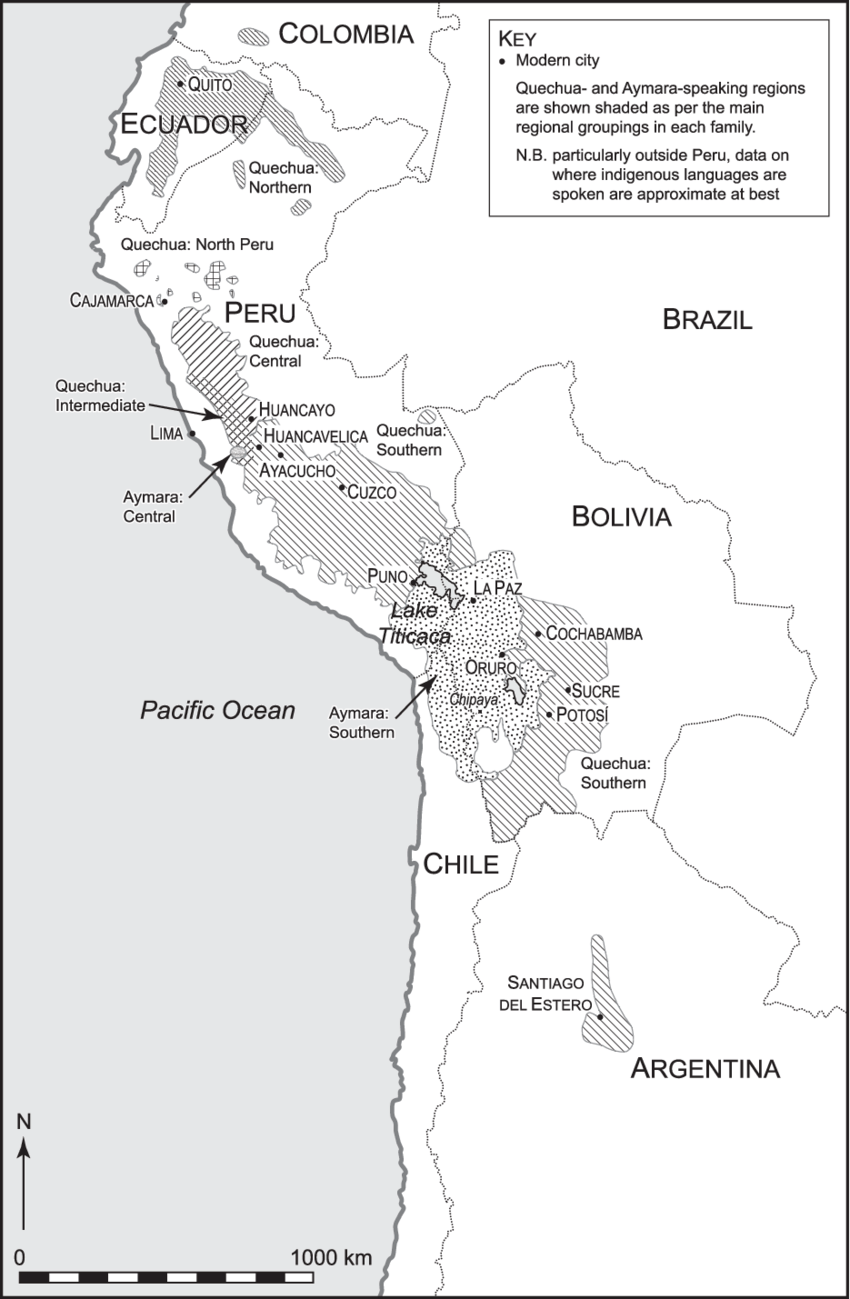

What follows below are two related articles I wrote on Aymara, Quechua and other Indigenous peoples’ resistance in Bolivia and Peru in the early 2000’s, which in part provided the context for the 2005 ascension to the Bolivian presidency of Evo Morales, who has now been removed by a US-backed military coup in 2019 (with American imperialist intervention being a frequent occurrence in Latin American history).

Some of the information in these articles comes from corporate media sources and therefore should be taken with a few grains of salt.

Since the Wii’nimkiikaa print magazine was never intended for non-Native audiences, it sometimes used the term “Indian,” still a colloquial term within Indigenous communities but not one that is recommended for use by non-Native people today.

– M.Gouldhawke

Indigenous Insurrection in Bolivia

by M.Gouldhawke

From Wii’nimkiikaa Issue 1 (2004)

In October of 2003, a massive social revolt overthrew the President of Bolivia, forcing him to escape to the United States. The uprising was the culmination of 500 years of Indigenous resistance to colonization and an escalating cycle of Indigenous insurrections which have swept the country in the past four years, involving a variety of tactics, including road blockades, the destruction of corporate and government institutions, and armed struggle against the police and military. Since the October revolt, Indigenous people have pushed forward, occupying land and estates, ousting police and politicians from several towns, and continuing to wage guerrilla warfare on soldiers who are invading their territory and destroying their land.

Bolivia is the poorest and least developed country in South America, and the Indigenous Aymara, Quechua, Guaraní and other peoples make up almost half of its population.

A major source of conflict between Indigenous peoples and the Bolivian government is the cultivation of coca. With the backing of the United States, Bolivia has been trying to eradicate Indian coca plantations under the pretext of the “War on Drugs”. Traditionally, coca has always been a part of Indigenous culture in Bolivia, and has many uses, including compensation for the thin air in the high altitudes of the Andean mountains. The coca plantations are also the only source of income for Indigenous peoples living on the land, and so they rightly see the Bolivian army’s attempts to eradicate coca as an attempt to eradicate Indigenous culture and the Indigenous people themselves, Many Indian coca growers were formerly employed in the tin mining industry, and are utilizing their skill with dynamite in their armed resistance to Bolivian soldiers and police.

Living under conditions of extreme poverty and exploitation, police brutality and murder, and attempts to privatize water and gas, Indians in the cities also have more than enough reasons to rise up and overthrow their rulers.

The current wave of insurrections began in April of 2000, as the government imposed martial law to quell resistance to the corporate privatization of water in Cochabamba, and street clashes left many people dead. For five days, the students at the University of La Paz used sticks of dynamite to defend themselves from riot police, and on May 29th in the city of El Alto, 20,000 people blocked Bolivia’s most important highway, fought with police, and then stormed the city hall and set it on fire. On June 15th, an Enron-Shell office was smashed-up and set on fire, followed by the July trashing of an office of the EMDEX corporation, a coffee exporter. In September, peasants occupied the Chaco Petroleum company’s processing plants, shutting them down.

Water War in Cochabamba

In October, more than a hundred young people in the city of El Alto attacked the offices of banks, multinational corporations and police stations, partly as an attempt to force the government to release political prisoners, and twenty people were arrested. In street conflicts that broke out in La Paz and Cochabamba, 159 people were injured by bullets and about 100 people were arrested, the majority of whom were later released. More than 10 people were killed by the army. Road blockades were built all over country and Indian peasants threatened to blow up electrical towers.

A General Strike took place in May of 2001, and in June, miners used dynamite in street clashes with police. In July, Indians armed with dynamite and gasoline firebombs occupied government buildings and took 60 hostages. They were acting as part of a movement of thousands of poor families who are in debt to banks and are fighting back. On July 15th, armed and masked Aymaras blocked a major highway, and on November 19th, clashes between farmers and soldiers broke out at highway blockades. 4,000 Bolivian soldiers were forced to retreat from a blockade on the Cochabamba-Santa Cruz highway, but several farmers were also killed in the battle.

In February of 2002, Indians killed three solders and a policeman in the Chapare region, while in Sucre, police squads were attacked with gasoline firebombs. In Pocitos, border workers battled police, forced them to flee, and then set fire to the Bolivia-Argentina border station.

The police station in Cochabamba was attacked by thousands of Indigenous peoples, workers and students, who threw rocks, firecrackers and paint at the building. When the police tried to disperse the crowd, a group of young people threw a bomb at them, injuring five policemen, including a senior officer. Highways throughout the nation were barricaded.

In January of 2003, Indians in the Chapare region formed the Ejercito Dignidad Nacional (the National Dignity Army) to defend their land from police and military invasions. President Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada announced a 12.5% tax increase, leading to clashes at highway blockades which left six dead and 50 inured. Police attacked students at the University of San Simon in Cochabamba, killing 14 and injuring 100.

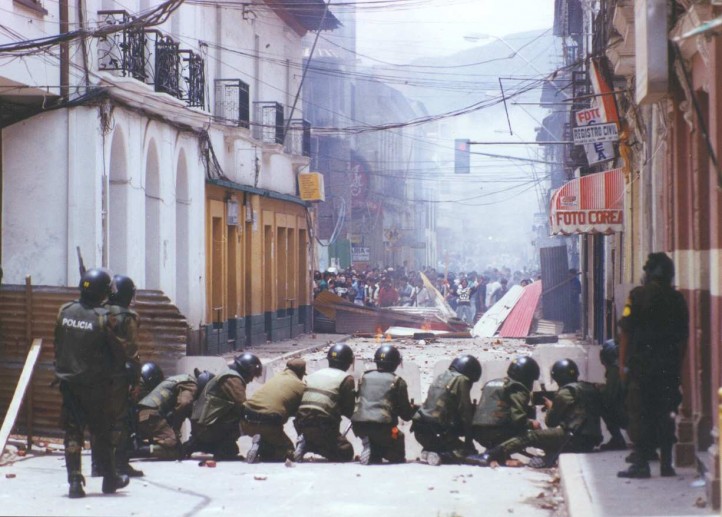

The conflict escalated in February, as an insurrection broke out in La Paz. 33 people were killed and 200 injured in clashes with soldiers, and banks, customs offices, government ministries, courts, and political party offices were looted and set on fire. The struggle continued throughout the summer and then exploded into the largest social insurrection yet. The events of September and October were called the War of the Gas, as the people rebelled against government plans to export gas to the United States through Chile.

War of the Gas

Government forces began to massacre Aymara Indians in September, sparking a wave of anger that quickly spread to all parts of Bolivia. The government could not be tolerated any longer and the people were determined to fight to the death. In the Aymara Indian town of Sorata, the local police station and court were set on fire, prisoners were set free, and cops, soldiers, judges and politicians were chased away.

Students and poor residents of El Alto repeatedly clashed with the police and military for over a month and more than 80 people were killed and 500 injured throughout the country. Wildcat strikes and road blockades sprang up everywhere, and Indians blew trains off their tracks with dynamite in order to block highways. Thousands of people from all over Bolivia converged on the capital of La Paz.

By October 17th, there were 500,000 people in the capitol city, erecting barricades in the streets, blowing up banks and fighting the cops.

President Lozada fled to the United States, and Bolivia’s largest trade union federation, the Central Workers of Bolivia (COB), accepted Vice President Carlos Mesa as Bolivia’s new leader, undermining the armed struggle of the Bolivian people.

In defiance of this peace treaty, Indians went on the offensive and occupied the former estate of the ousted president. Police used live rounds to block repeated attempts to occupy the estate of the former defence minister.

Sorata and several other Indian towns in the area continue to be “no-go zones” for the police in 2004. Community members make decisions in what they call “Open Councils” and the Indigenous Wiphala flag has replaced Bolivia’s at local schools.

At the beginning of April 2004, more than 8,000 Indian coca growers marched along the highway between the Yungas region and La Paz to attack an army facility under construction. They were stopped by police and clashes occurred, but they maintained a blockade of the highway for several days, with the determination to defend their crops and their culture.

Indians in the Chapare region continue to wage guerrilla warfare against US-trained Bolivian soldiers. Utilizing their skill with dynamite, the Indians have set booby-traps throughout the area and many soldiers have recently been wounded or killed.

Aymara Uprising in Peru

by M.Gouldhawke

From Wii’nimkiikaa Issue 1 (2004)

On April 2nd, 2004, more than 10,000 Aymara Indians converged on the town of Ilave and began a struggle to force the corrupt mayor Fernando Robles out of office. Highways and roads were blockaded and a General Strike shut down schools and businesses. Robles fled from llave to figure out a way to retake control. The stage was set for a major confrontation with the forces of order. Hundreds of years of poverty and cultural devastation were about to clash with the corrupt management of resources and funds on the part of elected officials.

The spirit of rebellion proved to be contagious, and residents of the town of Ayaviri seized the municipal building to demand the resignation of mayor Ricardo Chávez Calderón on April 11th.

On April 18th, about 200 Aymara residents of Tilali, a town near the Bolivian border, took over their municipal offices in order to oust mayor Melesio Larico, who is notorious for embezzling funds and artificially inflating the costs of public works projects. On April 28th, the conflict escalated, as five town council members were taken hostage. On May 2nd, an agreement was reached to suspend the mayor from office.

Residents of Paucarcolla seized their municipal building on April 20th, demanding the resignation of the mayor for failing to hand over funds for an electrical project.

The struggle in llave came to a head on April 26th, when the mayor was caught trying to hold a secret meeting with three town council members at his home. Enraged Aymaras broke through the fence surrounding his property, dragged him from his home and then through the streets, forcing him onto the roof of the municipal building, where he was made to offer an apology to the town over a microphone. After only a few words, he was dead.

The insurgent Aymaras proceeded to attack other town council members as well as journalists from the daily newspaper La Republica.

Riot police arrived and began to launch tear gas into the municipal building. At this point the struggle shifted into the streets, as thousands of Indians fought with police who did not hesitate to use both rubber and lead bullets. The Aymaras managed to overpower the cops and drove them back to their police station, setting their vehicles on fire along the way. Molotov firebombs were hurled at the police station, as Aymaras clashed with cops inside the building. Unable to match the force and determination of the Aymaras, the police were forced to flee the town. Later that night, police attempted to retake llave, but were defeated and driven back.

The following day, a small force of 220 cops entered the town, but kept a low profile, as Aymaras mocked them and chanted “llave united, will never be defeated.

The rebellion continued to spread, and the mayor or Cahuapana was taken hostage, along with two other officials.

On May 4th, more than 3,000 Aymaras arrived in the capital city of Lima, after an 11-day journey to oppose the government’s eradication of coca crops, which are an integral part of Aymara culture.

“They’ve put lots of poison in our fields to kill the coca, and the poison that they are using is not only killing the coca, it’s killing all types of products… It’s also causing cancer which is affecting the farmers there.” said one Indian woman.

Earlier in the day, riot police had clashed with Aymaras living in a tent city in front of the Palace of Justice, and at least one person was arrested.

On May 6th, Peru’s Interior Minister Fernando Rospigliosi, formally resigned because of criticism that he was unable to control the Aymara insurgency. Meanwhile, the Aymaras of llave fortified their positions, blocking bridges and threatening cops and journalists in an effort to prevent a major invasion.

On May 22nd, police and soldiers in the town of Tingo Maria fired tear gas to disperse rebellious Aymaras who had been maintaining road blockades and fighting off cops for days to protect their coca crops. Seven people were injured.

The government considered declaring a “State of Emergency” the next day, as the Aymaras of Ilave clashed with police at a bridge blockade and soldiers were sent in to restore the “order and discipline” of Peruvian democracy.

“Democracy YES! Disobedience and disorder NO!”

– Peruvian President Alejandro Toledo