Sometime in 2002, or just before that, I created a website to collect snippets of radical Vancouver history. I was inspired in part by a pamphlet that accompanied a walking tour of Vancouver’s labor history as well as the incredible book of oral history, “Opening Doors in Vancouver’s East End.”

The website is lost to time, but the content has been preserved. The section on squatting was made into an issue of the Woodwards Squat newsletter by a friend and comrade.

This overview was always limited, incomplete and begging to be added to. It remains unfinished but still not beyond the possibility for anyone to expand upon. As the WOODSQUAT newsletter showed so meticulously, history is not just collectively written but also collectively recollected and reconstituted.

– M. Gouldhawke, last days of 2019

Squatting in Vancouver – WOODSQUAT #53 (PDF for download)

For more on the Woodwards Squat see three articles collected in another post on this site, including Anarchy in BC: Anti-Capitalist Struggle Outside the Union on Canada’s ‘Left Coast’ – Roger Farr (2007)

Sḵwx̱wú7mesh village at Coal Harbour in Vancouver in 1886

Indigenous Title to the Land

Ever since the first arrival of Europeans in Vancouver, Indigenous peoples have continued to occupy their traditional territories in defiance of colonial rules and regulations. “British Columbia” is in fact a “squatters province”, in that European settlers continue to occupy the territories of sovereign Indigenous peoples without their consent.

Brockton Point Squatter Village

In 1860 Portuguese and Scottish sailors built log homes on the Brockton Point beach in what is now Stanley Park. The men married Indigenous women and a squatters community began to take shape. In 1888, when Stanley Park officially opened, a health inspector had the squatters homes destroyed during a small-pox epidemic. The families received $150 dollars in compensation and then rebuilt their homes. Developers were interested in commercial use of the land and wanted the houses removed in order to build a road.

In 1921 the city began legal eviction proceedings to get rid of the squatters. To establish any rights to their homes, the squatters had to prove 60 years of continuous residence. The squatters had no written documents, and the court ruled their oral history unsatisfactory. Only one squatter was able to win the case. The others appealed, but lost their cases in 1925. They were allowed to remain in their homes for a fee of a dollar-a-month until they were finally evicted in 1931. The Vancouver Fire Department burned down their homes.

One Brockton Point squatter family refused to take part in the legal proceedings, as they were upset that they had not been consulted when the land had been turned into a park. The Parks Board agreed to let the family stay for a $5 dollar-a-month fee. The family lived in their squatted home until their deaths. Agnes Cummings died in 1953 at age 69, and Tim Cummings died in 1958 at age 77.

Deadman’s Island Squatter Village

By 1909 more than 150 squatters were inhabiting an illegal village on Deadman’s Island, south of Stanley Park. The village sprung up in the late 1800’s just after the Brockton Point village formed. The squatters built homes on logs that would float at high tide, and rest on the shore at low tide.

The squatters were driven out of their village in 1909, but quickly returned. In 1912 the sheriff’s office burned down 40 of their homes.

The last of the fisherman squatters who lived on houseboats in their area were driven out by the 1940’s.

Waterfront Shacks and Hobo Shanty Towns

In the mid-1880’s, unemployed Chinese railway workers threw up huts on the marshes between Pender street and False Creek. After ten years, the city leveled the shacks but neglected to plan new housing in Chinatown. By 1894, at least 380 shacks lined the Burrard Inlet and False Creek shorelines, inhabited by Chinese, Native, and unemployed people. Once again the city destroyed the shacks, but the squatters kept coming back.

By the summer of 1931, about 1,000 homeless people occupied four east-end hobo jungles. One jungle bordered Prior street, close to Campbell avenue and the Canadian National Railway yards. Another existed under the Georgia street viaduct, a third was located on the harbour at the end of Dunlevy avenue, and the fourth was situated at the Great Northern Railway sidings. Shacks were built from boxes, boards and old cars.

In 1937 a total of 538 people were squatting the Vancouver waterfront, in houseboats, shacks and tents. Their numbers continued to grow over the next two years, despite attempts of the city to destroy their homes.

Cracking Buildings, Cracking Safes

In 1890 a string of robberies were leaving the police department baffled. Business after business had been broken into, the safes cracked with explosives, and all the money stolen. Police were at a loss as to how to catch those behind it all, until one detective suggested investigating the many abandoned and squatted houses on the east side. Police burst into a home that four men had been occupying, catching them off guard. There they found the loot from the robberies, as well as a huge arsenal of weapons that the squatters never had a chance to use.

The Finn Slough

In the early 1890’s a group of Finnish people moved on to land just south of Vancouver. They built 70 homes on stilts in a tidal area that periodically flooded. About 50 residents continue to live there to this day, and have never had any legal right to the land. The Finn Slough is the longest running squatter community in the greater Vancouver area.

Sam Greer

On September 26, 1891 the provincial government granted the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) hundreds of acres of land, including 160 on the Kitsilano waterfront, a site occupied by squatter Sam Greer.

He refused to leave and sheriff Tom Armstrong was sent to evict him. Sam shot the sheriff and was convicted of assault and sent to jail.

“Sam made one terrible mistake. If he had not fired that gun at Tom Armstrong he would have held his property. public opinion was so strong that the CPR would have had to give in, the people would have torn up the rails.”

Hotel Vancouver Occupation and Little Mountain Squats

600 homeless and unemployed World War Two veterans occupied the old Hotel Vancouver in January of 1946. After about two weeks the building was converted into a hostel that provided housing for between 1,000 to 1,200 veterans up until 1948. The building was sold to Eaton’s, who then demolished it, but the veterans moved to the Dunsmuir Hotel and stayed there until 1949 when the Salvation Army bought it and converted it into a shelter.

In 1946, two veteran’s families moved into and squatted barracks at the Little Mountain base near the University of British Columbia without opposition from the army and with considerable public sympathy. UBC later developed housing there.

Jericho Beach Hostel Occupation

In October of 1970 a group of 300 homeless youths occupied the Jericho Beach hostel in Kitsilano, and when evicted by the police a battle broke out, with rioting that spread to Jericho Beach. 25 people, and 6 police officers were injured.

The Mud City Squatters Camp

In the early 1970’s a squatter camp was set up along Georgia Street near Stanley Park. A vacant propert that was slated to become a Four Seasons Hotel was occupied after squatters tore down the fence surrounding the site and created a tent and shack city that lasted for about a year.

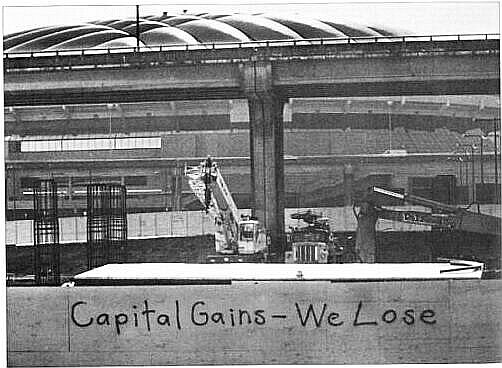

The Expo 86 Squats

“When the low-rental housing stock of Vancouver came under attack by EXPO ’86, the downtown core saw some desperate but organized squatting activity. What follows are some observations by some of the people who participated, and what they learned.”

– “It’s very important to be very clear and focused about who you want to squat with. It’s better to find a group of people to squat with before you enter a building. If other people come along, we’ll open other buildings to house them.”

– “If the focus is saving the building for social housing then you really have to organize with people in the community right away to ensure that you don’t get kicked out. A crash pad and a long term housing fight are separate goals.”

– “Security for women is important. A squat by its nature eliminates lots of young mothers and children who need a secure place.”

– “How can we develop a means to activate commitment to the squat, something to define and help maintain it? Our squat wasn’t a highly organized communal space because we were with people who were not used to living communally.”

– from Open Road #19, summer 1986

The Frances Street Squats

“We are some of the many squatters in Vancouver who are occupying several of the hundreds of habitable houses left vacant by developers. These houses have been slated for demolition and gentrification. In the face of unregulated rent increases, and out of necessity, we have chosen to squat as one of many viable means of protesting this atrocity. Housing is not a luxury, it is a right, and these houses are available now. New developments must be kept within an affordable price range for all people presently affected by the housing crisis. We are currently organizing various neighbourhood inclusive community events (potluck barbecues, daycare facilities, community gardening and recycling) in an effort to open up communication between squatters and paying tenants. We intend to defend these houses. We have been forced to go public at this time because we are in danger of losing our homes.”

– Vancouver Squatters Alliance press release

The Frances squats started as the word quickly spread of four empty houses on the street. One house was used as a wimmin-only space. The fences separating the backyards were torn down, a free store set up in a garage, and a community jamboree and potluck were held. After a few months a fifth house on Frances, a large four-storey home, was squatted. An eviction notice was served to tenants living in another house on the street, but they refused to leave, and their home became the sixth squat.

On November 25th the squatters put up barricades and set small fires in the middle of Frances Street as the threat of eviction grew closer. Over the next two days 6-foot high barricades were built in the street and in-door defenses were established. Squatters wore masks and some put on motor-cycle helmets. At 9am on the 27th of November, the Vancouver Police Department (VPD), 80 riot cops, 30 SWAT team members, the RCMP bomb squad, dog teams, fire trucks, and two earth-moving tractors violently evicted the squats. A large crowd gathered outside, shouting at and denouncing the police action. Several observers were arrested. Cops used the tractors to tear apart the houses during the eviction and nearly collapsed one building that squatters with gas masks remained inside of and were determined to fight for. Police spray-painted “VPD rules” on the back of one of the houses. A British Columbia Federation of Labour (BCFED) convention on the 28th of November condemned the eviction and called on the federal government to build social housing. Victoria Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) member Casey Swann said “The police went in with masks and they looked like assassination squads.” Jack Munro, president of the Industrial, Wood and Allied Workers of Canada (IWA), declared “Dumping people on the street in wintertime is a… disgrace.”

VPD spokesman Bob Cooper told the media “We’re quite satisfied with the action we took.” Mayor Gordon Campbell called the eviction a police matter, and not a political issue. City council (including Libby Davies) unanimously declared the houses a “public nuisance” and passed a demolition permit. The formerly squatted homes were demolished on November 29. By this date, all the arrested squatters and supporters had been released and a demonstration was held at Grandview Park on Commercial Drive. The angry crowd marched to Frances Street, and then on to the police station on Main Street chanting “Squat and fight! Housing is a right!”, where frightened police locked themselves inside the building and demonstrators attacked a police car outside. The crowd then moved on to Gastown and pushed over newspaper boxes. Motorcycle cops tried to surround the demonstration but the marchers linked arms in defiance. In the days after the eviction the squatters occupied Mayor Gordon Campbell’s office and set off a series of squatting actions.

“On November 27th, 1990, the SWAT teams of the Vancouver Police Department squashed six houses known as the “Frances Street Squats”. In a quasi-military operation they evicted 35 people from their homes and destroyed a community. It was an attack meant to extinguish the power and energy that had evolved at the squats during their nine-month life. They had to extinguish the energy that comes when a community of people take housing and their lives into their own hands.”

– from a flier announcing a re-squatting action by the Squatters Alliance of Vancouver East, June ’93

The Broadway Squats

“As of 4:00 pm, June 6th, 1993, two houses near the corner of Broadway and Commercial have been appropriated as a public squat. The squats are the result of a years work, bringing together ex-residents of the Frances street squats and others. We are mostly young people, living in poverty, and of a variety of races, sexes, sexual orientations and classes. Our aims in squatting these buildings are many. First, we see a need for a local community space that is free of government control in East Vancouver. The first floor of one of the buildings will be available to grassroots organizations for meetings, events, and as a workspace. Our second aim, like that of the Frances street squats, is to create a radical free space for activists to live and work. The second floor of the building will serve that purpose. Our politics are anti-state and we favour direct action against the idea of owning land and property.”

– from “An appeal to Vancouver Grassroots Organizations” by the Squatters Alliance of Vancouver East.

“What an exciting time to be in Vancouver! For the first time since the bulldozing of the Frances Street Squats a couple of years earlier there was a fun, lively, energetic, young spirit to local activism. A public squat was opened on Broadway, near Commercial Drive, and for its inauguration we staged a parade from the new condos on Frances Street to the new squats on Broadway.

We played another Frenzy benefit and in the summer we played at the I.W.A. hall on Commercial Drive as part of the Frenzy gathering itself. The three day gathering was full of shared ideas, shared food, spontaneous demonstrations, picnics, lots of new friends and old, and of course a heavy presence by the goons in blue, the Vancouver Police Department. When we played on the second night of the Frenzy shows, the cops surrounded the building. Were it not for their riot gear, guns, and paramilitary training, I´m sure we would have won.”

– Gus Braveyard of the Vancouver band Submission Hold

“We march up Commercial Drive chanting slogans and carrying a banner, stopping traffic. One cop car follows from a distance. We go to two houses on Broadway, two blocks off Commercial. The houses were previously ‘shooting galleries’, and we are told that they are a mess. We open the squats and hang the banner from one of the front windows. There are cheers. We proceed to clean up. There are ‘rigs’ and broken glass. The plumbing has been torn out. Everybody joins in and the atmosphere is very positive. Every body is helping out, cooperating. We get the place pretty cleaned up. We build barricades for the doors. We go dumpster-diving and driving around, getting mattresses, couches, chairs and blankets. About ten people stay the night. Some stay up all night.”

10 days later… The squat is all fixed and cleaned up. It’s immaculate. There are kitchen counters and more mattresses and blankets. I notice a flyer for a vegan feast with poetry and music at the squats for friday. There is a community garden, which some of the neighbours have planted in. We collected 150 neighbours signatures saying that they support us. Our next door neighbour provides us with electricity and water via an extension cord and a garden hose. The toilets work. One of the houses is a ‘women and people of color only’ space.”

– from “Flour Power” #1, June ’93

“On Saturday, July 31st, at about 4 o’clock we got word that a notice had been placed on the door at the squat. We looked at it and decided to hold an emergency meeting for everyone at the Frenzy festival workshops to attend. We told people what was happening and asked them for support in defending the squats. Some of us went back to the squats. Since it was eviction day, a lot of the people who had been living there had just left. Those of us remaining decided to barricade ourselves in. We filled two buckets full of water and stock-piled candles. We had a canister of fuel for the stove but we didn’t have much food. Boards were nailed over the windows, and all the doors were barricaded except for one. We asked everyone staying at squats in the city to support us, but a lot of people couldn’t risk it because of criminal records or threat of deportation. Some people just backed out. We went back to the Frenzy festival and told everyone that the last barricade was going to be put up at midnight, or when the cops came. We told them that to support us they could barricade themselves in with us, or they could sit in the yard and block the way, or they could stand on the sidewalk to be witness. We also told people that we needed food. At the end of the gig Tchkung led 200 people on a march to the squats. We were showered with donations of food from neighbours and people from the Frenzy. 50 people barricaded themselves in with us. It was an amazing show of solidarity. Nothing happened that night or the next morning. Nothing went down all week and almost everybody who was staying for the Frenzy festival left. There were only a few people staying at the squats.”

“Early the next Monday morning two people from the board of engineers came in one of the unbarricaded doors and woke us up, telling us all to get out. People got their stuff and left. They removed the barricades.”

“I came back the next day to get my stuff. They had torn the staircase down and smashed in every window. They smashed the toilet and knocked over the bookshelf with zines and newsletters and had strewn them around. They trashed people’s stuff, including the stuff I came to pick up.”

“The next day a friend rode by the squats on his bicycle and the squats had been leveled, and I’ll bet you those lots are going to stay vacant for a long time.”

– from “Flour Power” #3, August ’93

The Salsbury Drive Squat

“On October 31, 1997 little kids were busy scrambling from house to house getting candy, while a group of big kids had their sights on one house only.

In the darkness of Hallowe’en night a group which calls itself the Direct Action Against Homelessness crept into an abandoned building in the 1000-block of Salisbury. The building which has been abandoned for over a year had served as an old person’s home and hospital. And the Glenhaven Hospital stills smells like it on the inside. The stench of bedpans or death, you pick.

While the little kids were wandered around with their parents collecting candy the big kids set themselves up in their new home, the Monster Squat. They cleaned up the kitchen first, washing everything: dishes, floors, fridges, walls, an old dishwasher, everything! Food was donated by various groups and volunteers organized into chores; the most important task being the cooking and feeding of all these hungry squatters. Everybody was laughing and playing; it’s Hallowe’en and friends pitched in cleaning and cooking, and eating. An instant family of concerned big kids.

Over the weekend the abandoned building served as a soup kitchen feeding many people and as a community centre: a space for artists, activists, meetings, and homeless people. For three days it was a blissful space. It was the most incredible squat. A lucky find for people with no where else to live or sleep the night. Free food and happy volunteers cooking and cleaning.

All the electricity and heat was already turned on. The water flowed, and the roof didn’t leak (except in one spot). It was a huge building: big enough for over a hundred people, and wired for cable TV (think of the possibilities!). This was no ordinary abandoned building. It is a heritage building and it is left idle and empty, awaiting its destiny; to be demolished and turned into yuppie condos. A few concerned big kids decided this was a crying shame and decided the space was better used as a temporary shelter, soup kitchen and community centre.

Monday morning the landlord showed up, we asked him if we could stay until the building got demolished, he was not willing to negotiate. He pulled out his cell-phone and called the cops. When the cops arrived they kicked in the door and told everyone to leave. That was that.

In Thursday’s Vancouver Sun (Nov. 6/97) Constable Anne Drennan, with the Vancouver city Police, said that the group were not squatters–they were not homeless persons.

“They were making a political statement about poor housing conditions.”

What’s wrong with that?

For one full weekend we fed hungry people, gave homeless people a place to stay and brought a community more closely together. This is political and it is directly taking action against abandoned buildings that could be livable spaces.

In same story about the “so-called squatters” they also said that they needed that space for an episode of the X-Files that will be filmed there. Some things are more important than homeless people–yuppie condos and popular TV programmes.

As long as we have our priorities straight….”

The Monster Squat – Direct Action Against Homelessness

by Mat X