By M. Gouldhawke (Métis & Cree)

Wii’nimkiikaa (It Will Be Thundering)**, Issue 2, 2005

“When movement passes were introduced at P4W [Prison for Women] in 1982 or 1983, they echoed another history. Our ancestors were required to obtain passes from the RCMP or from the Indian Agent to travel off reserve. Now we required written permission to go up a flight of stairs or to move three feet from ‘A’ Range to the hospital. Our ancestors also understood that such laws were made to be broken.”

– Fran Sugar and Lana Fox, Survey of Federally Sentenced Aboriginal Women in the Community, 1990

Christian missionaries played an essential role in building the British colony of Canada. Missionaries and fur traders were the initial reconnaissance forces who first contacted Indigenous peoples and exposed them to diseases and alcohol, beginning the destruction of Native cultures. Once soldiers and police militarily defeated Indigenous peoples and imprisoned them on reserves, indoctrination into the European system became more systematic and efficient. The colonizers understood that to suppress Indigenous insurgency over the long term they had to break the spirit of the people. The reserve system opened up territory for settlement and industrial development, while providing the missionaries with a captive audience.

Assimilation was entrenched as official government policy with the “Gradual Civilization Act” of 1857, which became the “Indian Act” in 1876. The Act was amended in 1884 to ban spirit dancing and the potlatch, and in 1895 the legislation was revised to also criminalize the sun, grass, and thirst dances. Indian Agents and North West Mounted Police (later renamed the Royal Canadian Mounted Police) enforced the bans and destroyed sweat lodges, even though the lodges weren’t specifically prohibited by law. Jail terms of two to six months could be brought down on an Indian convicted of participating in spiritual ceremonies. Indian Agents also acted as ‘justices of the peace’ and had the power to conduct trials wherever they decided.

Police and Indian Agents controlled the movement of Indigenous peoples on the Prairies with the pass system. To leave a reserve, a written pass from an Indian Agent was required. The document only allowed for travel to the location written on the pass and for a period of time decided by the Agent. Those found without passes could be charged and prosecuted by an Indian Agent for ‘trespass’, under the Indian Act, or ‘vagrancy’, under the Criminal Code. The pass system served to isolate Native communities from each other and to inhibit coordinated resistance to colonization. This became very important to colonial officials because of the Métis and Cree resistances of 1869 and 1885.

Under an Indian Act amendment in 1884, attendance at Christian Residential Schools became mandatory for Indians less than 16 years of age. These schools were yet another form of incarceration, which included systematic mental, physical and sexual abuse, and often death. Children were severed from their families for the majority of the year and forbidden from speaking their own languages. Indigenous culture and spirituality was intentionally shattered and replaced with Christianity and manual labour. European ideas of White supremacy and patriarchy (male rule) were imposed upon Indigenous peoples at an early age.

In 1951, the Indian Act bans on spiritual practices were lifted, but Native people in Canada’s prison system continued to be denied spiritual freedom. Attempts to practice spirituality were suppressed by prison officials and guards, often with violence (including the use of White prisoners against Native inmates)

In 1981, American Indian Movement (AIM) members and cousins Dino and Gary Butler of the Siletz Nation (Oregon, US) were arrested in British Columbia after a shootout with police. They had come up from the U.S. to help with a Vancouver rally in solidarity with fellow AIM member Leonard Peltier, who was framed for the killing of two FBI agents on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota in 1975 (Dino was also charged with killing the agents, but was acquitted). In the 1970’s, the spiritual strength of the Lakota people at Pine Ridge (symbolized and embodied in the 71-day armed occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973) greatly influenced Indigenous peoples and resistance movements across North America. This influence also carried over to the struggle for Native spirituality inside Canadian prisons.

When Dino and Gary Butler were brought to trial in BC, they refused to walk into the courtroom in shackles and were dragged away. They went to the Supreme Court to regain their eagle feathers, pipe and medicine bundle, but were forbidden from using them at their trial by judge Allan McEachern*, who also ordered the court sheriffs to stop Native supporters from drumming and singing in the court waiting area (although the supporters ignored the sheriffs). The Butlers dismissed their lawyer and refused to speak during the trial. They were convicted and sentenced to five years at the Kent maximum security prison. At the time, the population of Kent was 30% Native. Requests for a sweat lodge had been rejected by the warden.

On March 30, 1983, Gary Butler began a spiritual hunger strike and was put in isolation. Two days later, Dino joined the strike, and few days after that, Stuart Stonechild also joined in. Outside support groups rallied in support of the prisoners, while prisoners at Oakalla and the Regina Correctional Centre joined the strike in solidarity with those at Kent. Other Kent inmates showed support with short fasts and work strikes. The struggle gathered national attention and was discussed in Parliament. After 34 days, the strike came to an end when the prison officials agreed to create procedures allowing for some spiritual practices. Many of the hunger strikers were transferred to different prisons across Canada, but carried the spirituality struggle with them.

On October 30, two of the Native prisoners that had been part of the hunger strike, Willy Blake and Stuart Stonechild, crawled out a window in the prison’s schoolroom into the fog, snipped through the perimeter fences with wire cutters and escaped. They were recaptured later that day and put in isolation. Despite the procedures worked out after the hunger strike, Blake and Stonechild’s medicine bundles were taken from them while they were in isolation. Prison staff desecrated Blake’s medicine bundle by opening it and dumping its contents on the floor. Several days later, when Blake requested his medicine bundle back, he was lied to and told that the RCMP were holding it as evidence. For weeks Blake requested to have his medicine bundle returned and for visits from elder spiritual advisers. On December 7, Willy Blake and Stuart Stonechild were convicted of escape. Five days later, Blake was handed a paper bag containing his desecrated medicines. On December 21, Stuart Stonechild was released from segregation to await his transfer to another maximum security prison. But Willy Blake continued to be held in segregation, because the Review Board felt he had a “hostile and abrasive attitude” towards prison staff. This was how the officials saw fit to get ‘payback’ for the embarrassment caused by the hunger strikes.

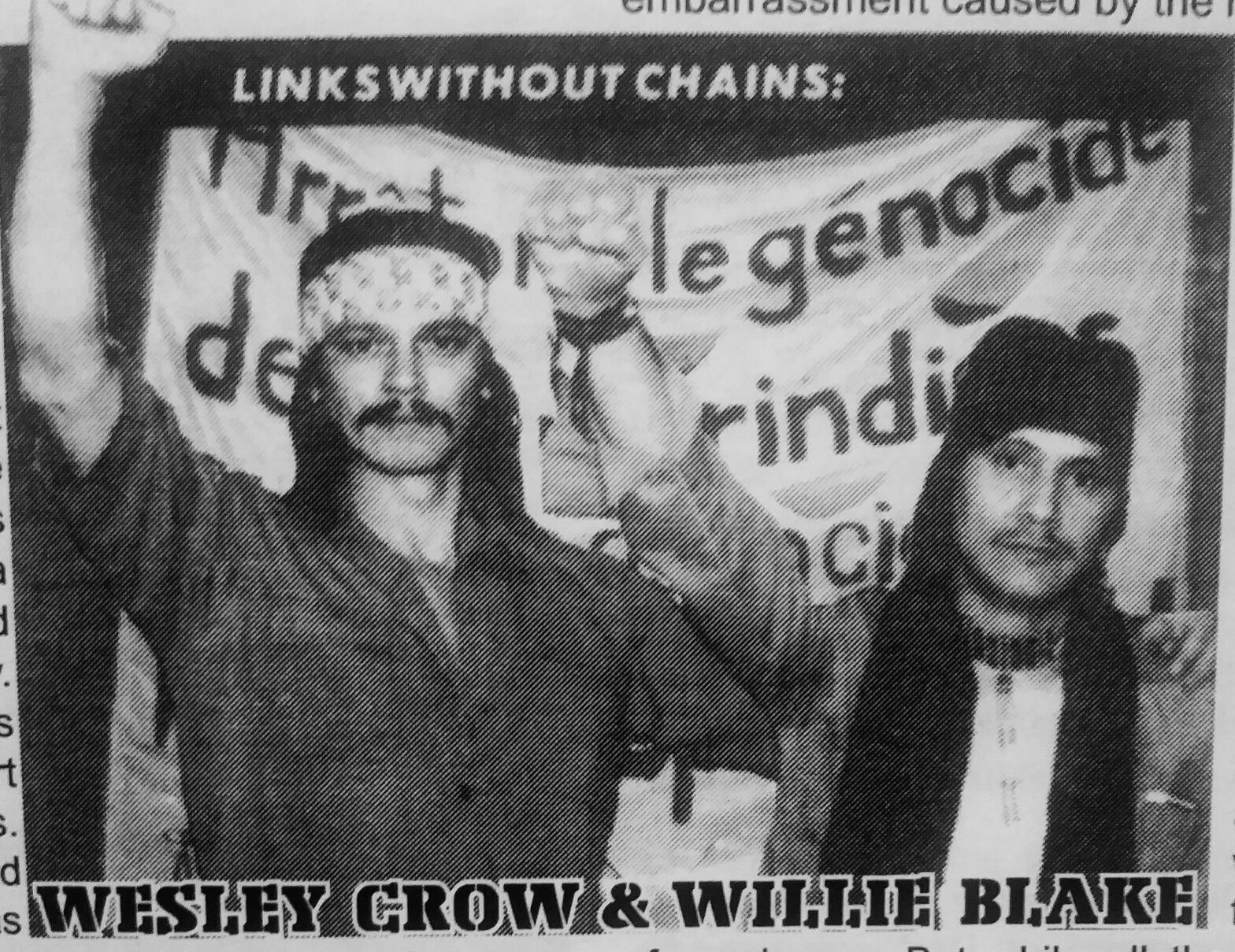

Three years later, in 1986, Willy Blake and Dennis Okeynan went on hunger strike against the harassment of Native prisoners at the Edmonton maximum security institution. Wesley Crowe joined the strike six days in. Blake, Okeynan, and Crowe were among 31 prisoners (mostly Native) rounded up and put in segregation, without charges, following the stabbing of a prisoner. But while all the other prisoners were gradually released from segregation, Blake, Okeynan, and Crowe were held for almost two months, allegedly because of Willy Blake’s “influence” over his fellow Native prisoners. Vigils were held in support of the three hunger strikers and phone calls from across Canada and the US helped to convince the warden to release the men after two weeks. The two prisoners who were eventually charged with the stabbing were allowed to bring medicine bundles to court for the first time in Alberta’s history.

In 1990, the armed Mohawk resistance to the expansion of a golf course at Kanehsatake, and the Canadian government’s military response, sparked solidarity actions by Indigenous people across the country, including Native prisoners. Solidarity ceremonies, vigils, riots and hunger strikes took place within numerous institutions. At the Headingley prison in Manitoba, Brian Ellis (Dene) and Bill Creely (Cree) held a three-week fast in solidarity with the Kanehsatake defenders. “Spiritually, I gained a lot of strength from fasting and praying for those people.” said Ellis. Both men were honoured in turn by their fellow Native inmates, who held a two hour pipe ceremony for them.

At the Prison for Women (P4W) in Kingston , Ontario, a group of 15 Native women prisoners took part in a solidarity fast for the Kanehsatake Mohawks. One of the fasting women, Careen Daigneault, would be found unconscious in her cell and later die in hospital. It was only with the Native Sisterhood at P4W that Daigneault had begun to embrace her Native background and practice Indigenous spirituality. She was also one of four Native women inmates who committed suicide at P4W within a two-year time period. Added to these was Pat Bear, who hung herself in a park just after her release from the prison in 1990, and Janice Neudorf, who survived a hanging attempt, only to suffer major brain damage. In at least two cases, prison staff did not inform the other inmates of the suicides. Several of the women were known to be suicidal and had a history of slashing and suicide attempts, and yet prison officials did nothing. In 1991, an inquiry was held for three of the cases. Members of the Native Women’s Association of Canada walked out of the inquiry after a racist remark was made by a lawyer to Fran Sugar during her testimony. The Association also objected to the evidence presented and the prison-biased nature of the process itself.

In 1994, a small conflict between inmates (many of them Native) and female guards at P4W was used as a pretext for raiding the segregation unit with a masked male riot squad (Emergency Response Team). A video-tape of the patriarchal brutality and torture perpetrated by the squad during the raid was later publicly aired, creating yet another scandal for the prison. Two weeks after the assault, six of the prisoners were transferred to a segregated range at the men’s Kingston penitentiary. The rest of the women were held in segregation at P4W for up to eight months, and were deprived of bedding, clothing, writing materials, exercise, and family contact. Two women staged a hunger and thirst strike for three days to resist the conditions in segregation. In 1996 the Canadian government’s commission of inquiry into the “certain events” which took place at the Prison for Women in 1994 recommended that the prison be shut down. P4W was built in 1934, and within four years of its opening a royal commission recommended it be closed. It was finally shut down in 2000. Over the next several years, women prisoners were held in segregation at various men’s maximum security penitentiaries across the country.

In February of 2003, three Native women prisoners at the male Springhill institution in Nova Scotia initiated a hunger strike to be allowed to attend sweat lodge ceremonies, to be transferred to a women’s prison, and to be allowed to reduce their security designations through prison programs.

The repression of Native prisoner’s spirituality continues in 2005. The newspaper Windspeaker published a report in February on the recent banning of sweetgrass in Alberta prisons, a ban proposed and enforced by the Alberta Guards Union. Mike Rennick, a union spokesman, said that Native inmates can go outside if they want to burn sweetgrass. “If it’s minus 25 and it’s that important to you, then brave the cold” he recommended, “the Christian Bible doesn’t kill me – sweetgrass is carcinogenic.”

Also in February, six Native inmates at the Regina Correctional Facility in Saskatchewan filed complaints stating that they were not being allowed to attend sweats or possess sweetgrass. Prisoner Ryan Sayer said that guards mocked his eagle feather, tore open his sage envelopes, and aren’t allowing him to see an elder.

“It’s a struggle” said fellow inmate Daniel Brass.

Note:

* In 1991, Justice Allan McEachern quoted Thomas Hobbes in referring to Native life before colonization as “nasty, brutish and short,” and asserted that Aboriginal rights had been “extinguished” by the colonial government, in his dismissal of the Gitksan-Wet’suwet’en “Delgamuukw” Supreme Court case. McEachern also presided over an appeal by Ts’peten (Gustafsen Lake) defendants and voiced his disagreement with their belief in Native sovereignty. McEachern is presently chancellor of the University of British Columbia.

Sources:

Prison of Grass, by Howard Adams

Open Road (defunct Vancouver anarchist newspaper)

Publication note:

**Wii’nimkiikaa – It Will Be Thundering – was a short-lived but sparky Indigenous resistance magazine with an international focus (intended only for an Indigenous readership), which was started, edited and designed by an Anishinaabe woman, friend and comrade of mine in 2004, for which I wrote several articles (and she also wrote for the magazine.)

See also:

History of Prisoners’ Justice Day

“On the first anniversary of Eddie´s death, August 10th 1975, prisoners at Millhaven refused to work, went on a one day hunger strike and held a memorial service, even though it would mean a stint in solitary confinement.”

Almighty_Voice – Hear Our Words of Truth (PDF)

(A publication from the 1980s by the Native Brotherhood at Kent Institution, a federal prison in so-called “British Columbia”)