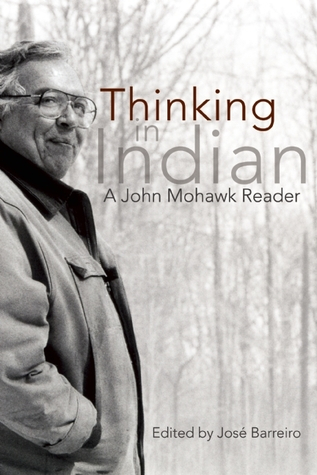

Originally published in the Akwesasne Notes newspaper in 1981 and reprinted in the John Mohawk reader “Thinking in Indian”, published in 2010

By John Mohawk (Seneca Nation)

There are clear differences between what is widely accepted as Marxist ideology and the ideologies that comprise the Native Peoples’ movements. While both movements are avowedly anti-colonialist, anti-imperialist, and anti-capitalist, it will be seen that the two traditions have entirely different roots. The Native Peoples’ movement expresses an ideology that is, by definition, primarily anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist and that emphasizes cultural diversity. Marxist ideology, on the other hand, is primarily anti-capitalist, and is unquestionably anti capitalist imperialism and anti capitalist colonialism. Many will be surprised that these two ideologies have very different objectives. In fact, Marxist-Leninist thought and the ideologies of Native Peoples’ movements are so different that the question arises whether the two are in any way compatible at all.

For the purpose of discussion, it will be useful to speak only in the most general of terms of a Native Peoples’ movement because there is not a tradition of a published ideology comparable to the classic works of Marxism. At the same time, there are many Marxist tendencies and almost any general statement about Marxism is almost certain to misinterpret some tendency of Marxist thought. Although there are fundamentalists within both groups, it would be unfair to state that either Marxists or Native Peoples’ movements are ideologically static. Both are capable of responding to changing realities and each appears able to incorporate the thoughts of the other to some degree.

Native Peoples’ movements constitute a class of ideologies that have arisen, in recent centuries, in response to imperialism and colonialism. Although highly complex and variable in nature, these movements tend to find their roots in the history of specific nations and peoples and their struggle to survive in the face of expanding imperialist (and more recently, industrial) cultures. The ideologies of these movements tend to be pro-nationalist (with a cultural definition of nationalism), anti-colonialist, and anti-imperialist, anti-industrialist, pro-regionalist, anti-capitalist, and, not surprisingly, de-centralist. The Native Peoples of the Western Hemisphere are one of the groups of nations and peoples that comprise this class of movements, but there are many other Native groups throughout the world that adhere to similar principles. There are also ideologies within or on the fringes of the Western tradition that propose very similar ideologies, especially the “back to the land” and neo-tribalist groups that promote human-scale societies and regionally appropriate economies.

Marxism is an ideology that arose in response to the Industrial Revolution. It is today a highly developed, extremely sophisticated intellectual and political tradition that, because of its origins in western Europe, is primarily anti-capitalist. The tradition known as Marxism consists basically of analyses of capitalism and a vision of a post-capitalist society. Marxism is based on the premise that a ruling class exists within the industrial (and specifically capitalist) societies and that the ruling class interests exploit the labor societies and the labor of the working classes. According to classical Marxist prophesy (which is somewhat more of a subjective matter than Marxist analyses), this imbalance of power and exploitation will cause the workers to eventually be oppressed to the point that they will rise up and overthrow their exploiters, the ruling class.

The Native Peoples’ movement, at least some sectors of it, has prophesies also. According to Native Peoples’ prophesies (which are also different from the Native Peoples’ analyses), the whole of industrial society is exploiting the physical world to the point that someday the Natural World will be unable to continue to provide the necessary materials for industrial society and the latter will experience some kind of collapse, often initiated by some form of natural disaster.

Both movements predict crises in the capitalist modes of production and economy. Marxism promotes that this crisis will be precipitated by the workers, and the Native prophets state that man-made alterations of the environment will trigger events that take the form of natural disasters (droughts, changing climates, crop failures, etc.) or wars that will destroy the base of industrial society and possibly destroy the basis of human inhabitation of the planet or large parts of the planet.

The Native movements, which see industrial society pitted against Nature, find Nature to be a source of both psychological and economic sustenance. Although Native Peoples employ specific and sometimes fairly complex technologies to maintain their societies in parts of the world that require such technologies, these movements are considered anti-technology because when they speak of technology they are specifically referring to the European development of industrial technology, which they oppose.

Marxism is an ideology that developed as a critique to capitalism. Marxist critique is sometimes criticized because it views all political movements and definitions within the framework of the struggle between Marxist and capitalist ideologies as though no other ideologies exist or could exist. Marxist writers very often write as though there exist in the world only capitalism and Marxism, and they often describe political thoughts or analyses that are not their own as having either capitalist (or bourgeois) roots or being incorrect (counter-revolutionary) Marxism.

Despite this sense of the world in terms of black and white, Marxism and capitalism, the two ideologies do have some striking things in common. Like capitalist ideologists, Marxists generally see nature as an object to be manipulated and exploited. Marxism has developed the almost automatic response that any subjective view of Nature must be a product of bourgeois romanticism. (Capitalists, incidentally, share an aversion for romantic idealists, especially on environmental issues.)

Marxism generally tends to view industrial technology as being almost universally benevolent, and their definition for “progress” sounds alarmingly similar to the definition that capitalist technocrats have for that word. The Marxist tradition, which has developed a simply marvellous methodology for the analysis of capitalism, has simply never been able to apply the same kind of methodology to industrial technologies.

Marxist thought also sees religion as a threat, a diversion from the work of organizing the proletariat against the ruling class, the oft-mentioned “opiate of the proletariat.” There are of course leftist and Marxist tendencies that do not accept this definition of religion, but the general flow of Marxist ideology holds that religion or spirituality of any kind serves the interests of the ruling capitalist classes.

The Native movements, on the other hand, view spiritualism (which the Marxists would identify as religion) in an entirely different light. Some Native peoples speak of “liberation theologies” and they base their spiritualism on a reverence for Nature. Native movements have been averse to the use of scientific evidence to move their arguments forward, a development that fundamentalist Marxists would find a contradiction. Marxism finds religion a contradiction to science. The Native Peoples’ movements, especially during the twentieth century, have looked to scientific evidence as a source of proof of their views that industrial technologies are a danger to the Natural World and to peoples who would depend on the Natural World for their existence and survival. Native Peoples also point to their perception that although industrial peoples may not have developed an awareness of reality, they too are dependent upon the Natural World for their survival. Spiritualism, then, is an important ingredient to Native Peoples’ movements, although it is a Natural World spiritualism that is in many ways a complete contradiction to the spiritualism or religion of the industrialized West and has a completely different history.

The social objectives of these two movements are also substantially different. The Native Peoples often express a strong desire to promote the health and survival of the extended family. They see the social institutions of the industrial societies as a threat to the family. in general, and to the extended family, in particular. To Native Peoples’ movements, the extended family offers an alternative to technocratic, hierarchical industrial societies. The Native movements assert that Native Peoples compose small nations and peoples of the world, and that such nations and peoples have rights to continue to exist, to be self-governing, and to determine their own destinies. Since this ideology promotes local autonomy and the development of the integrity of local communities, and since the idealized Marxist industrial society (called socialism) requires that its members’ needs be met by a huge and centralized nation-state apparatus, the two movements differ greatly in this area. In fact, even in those countries where Marxist ideology is characterized by a tendency with a reverence for the family, there exists a contradiction that is glaring, at least in ideological terms.

There are other areas in which Marxist ideology and practice are clearly contradictory to the objectives of Native Peoples’ movements. It seems unlikely that a huge socialist industrial country would be supportive of the claims of small nations and peoples to local autonomy and cultural identity. The history of the Soviet Union under socialism is not a model that champions the rights of it “national minorities.” In fact, it is open to question whether it is possible for an industrial society, under either capitalism or socialism, to be a model that champions the rights of its national minorities. In fact, it is open to question whether it is possible for an industrial society, under either capitalism or socialism, to avoid being a colonialist power. Suppose that a Marxist country found out that it was cheaper to import raw materials from some pre-industrial society that had been colonized. History has shown us that countries like the Soviet Union have chosen to go to the world market to purchase raw materials (such as rubber) from capitalist suppliers who acquired those materials from the lands and labors of Native peoples. In that sense, Marxist countries are subject to participating in colonialism because the nature of industrial societies is that industries need raw materials that are to be found in the lands of pre-industrial (or post-industrial?) societies. Industrial societies depend on the mass market and are, by definition, colonialist in nature. Capitalist and socialist ideologies share the same view on this subject. Given uranium deposits on the lands of Native Peoples, there is nothing in Marxist ideology that would prevent the exploitation of that resource even if the result is the predictable destruction of whole cultures.

A student of Marxist ideology could easily conclude that the planet Earth is endowed with practically infinite material wealth, which, given the proper social organization, could benefit all the masses of the earth in the form of material enrichment. Within that ideology is the assumption that all the peoples of the world could, given the fall of capitalism, become industrialized. The peoples of Burma and Thailand could become industrialized, the peoples of the Sahara and the Gobi, the peoples of the rain forests of South America – all could be integrated into a world society of industrial workers. The product of all that industrialization would be a controlled economy, run for the benefit of the proletariat, that would see to everyone’s material needs for an indefinite amount of time.

The oil that would fuel the cars of industrialized Nepal and Madagascar would be found and developed. Nuclear power could be expanded indefinitely and, under socialism, that technology would automatically be improved and made safe. Marxist ideology is, to be kind, pretty idealist.

An ideology that envisions an industrial society, whether run by workers (if that were possible) or by a capitalist (or socialist) ruling class, is bound to conflict with an ideology that favors local autonomy and locally appropriate economies (and thus technologies.)

The reasons for this are to be found within the basic structure of Marxist thought. According to the tenets of Marxism, capitalist class interest will create such oppression that the proletariat will be forced to violent revolution to overthrow the ruling class. Following the revolution (which, by the way, has yet to happen in any industrialized country and which happened in the Soviet Union prior to Russia’s period of industrial development), avant-garde elements of the revolutionary intelligentsia will take control and organize the country to bring socialism to reality. The emphasis here is heavy on the concept of organization and hierarchy. This organization is to be undertaken by an intellectual bourgeoisie that, in fact, has evolved into a privileged managerial class that serves functions very much like those served by the ruling class under capitalism. The proletariat will benefit from this benevolent hierarchy because there will be a more equal distribution of goods and services, and because there will be full employment in a workers’ paradise. This emphasis on hierarchical organization and the conscious creation of a privileged managerial class has caused critics of Marxism to assert that Marxism is, after all, a bourgeois ideology.

When Marxist theory was first formulated, the industrial age was fairly young, and people had not yet been faced with the horrible excesses of industrialization, nor did they have a full appreciation of the pitfalls of bureaucratic hierarchies. There were, in those now-forgotten times, no reports of such phenomenon as the Love Canal, no worries about oil or wood shortages or any kind of material shortages. The idea that there might one day be major accidents involving nuclear waste dumps, accidents such as are reported to have occurred in the Soviet Union, had not yet surfaced. Marxism was born in a day before these things were known. It was a time when industry could be idealized and industrial societies could be idealized, and when genetic mutation and nuclear pollution were the subjects of science fiction and not the day’s newspaper headlines.

Modern Marxism is saddled with assumptions that were appropriate to the mid-nineteenth century. Marxist analysts generally ignore or deny that there are any material shortages in the world or that there will be such shortages. They assert, in their role as prophets, that technologies will be developed that will solve any of the industrial world’s problems – a prophecy much in agreement with prophecies of their capitalist counterparts. Marxist ideology is clearly committed to promote the opinion that whatever benefits the need of the industrial proletariat, be it oil drilling in the Arctic, or uranium on the tundra, is justified. If any local peoples happen to be living where the minerals are, their existence must be sacrificed to the needs of the proletariat. That justification is, of course, a lie. The real reason that peoples are sacrificed under socialism is that Marxism creates a ruling (call it a managerial) class that has the same interests in this development as the ruling class in capitalist society.

Marxist ideology is historically a bourgeois ideology in the sense that all practically all of its inventors and theoreticians were members of the bourgeois class. It seems without question that most of its organizational fetish is a product of that bourgeois influence – the bourgeoisie, however radical, has a subconscious fear of the masses. Thus the new bourgeoisie is given a role in Marxist ideology – they are to be the intellectual elite, the party members, the “dictatorship of (over) the proletariat,” the non-workers in a workers’ paradise.

The Native Peoples’ movements generally seek egalitarian social structure in a post-industrial society, and there is a considerable amount of assertion that class structure of any kind is to be avoided.

The basic theoretical conflicts between Native peoples’ movements and Marxist ideology lie in the disagreements between the prophets of the movements. The prophets of the Native movements seem to be saying that capitalism and all of industrial society must eventually come into crisis because the material base of their society is finite and has physical limits. When those material limits are reached and exceeded, the industrial society will come into crisis.

The differences between these two movements can be seen as differences between a movement that originates within industrial society and one that originates outside of that society. At least some of the differences reflect the different realities that face Native Peoples and those realities that are faced by industrialized peoples.

Native prophets state that what will happen is that industrial societies will over-extend themselves in the physical world. There are a number of tendencies to these prophecies, but it seems generally to be true that Native prophets see the collapse of industrial society as a product of the exhaustion of the Natural World, although they are usually absolutely specific about whether that means that it will run out of energy or raw materials or it will pollute itself to death. It is probably safe to state that most of the Native prophets and prophecies do not find it impossible that industrial society will do both. Wars are sometimes predicted.

It is interesting to speculate that the Native prophecies could conceivably come to pass even after the Marxist prophecies had come to pass. That is, it could happen that the workers’ paradise could experience crisis because of coal or iron ore shortage, or widespread poisons that result in the use of chemicals in technology could cause massive social and economic disruption. Wars are always possible, and wars of the atomic age seem likely to be able to bomb the human race “back to the Stone Age,” or into infinity.

Marxist prophecy makes two general predictions. The first (which now reads like early Christian expectations of the second coming of Christ, which they expected within the first two centuries AD) is that the oppressed proletariat will rise up and overthrow the ruling capitalist class. The second is that some form of mismanagement or false management of the world capitalist economy lead to a crisis that will cause the world market economy to collapse. This area of prophesy has many variations (and the market economy collapse that focuses on the expectation of currency failures is very recent and not correctly Marxist in origin), but all conclude that the world economic crisis, which will cause capitalism to go into serious crisis, will trigger revolutions around the world.

Marxism offers a future world of an industrial paradise where the workers’ needs are taken care of by the state and where material want has been eliminated. The Native movements prophets offer a future world where humans are interdependent with the forces of Nature, where there is little state power but great local autonomy, and where the workers (although they would not refer to the people as workers) are the consumers of the products or their own labors. Some Native prophets offer a future that is considerably more bleak – a world in which Nature has been all but destroyed and where people exist on the submarginal remains of the world’s ecosystems.

Aside from the assertion that Marxism is ultimately a bourgeois ideology, the single most damning accusation brought by Native Peoples and other critics is that Marxism is simply a distillation of capitalist industrialist Western society. Some Native political philosophers believe that Marxism is exactly what so many Marxists promote it to be, the most efficient form of social organization for industrialized man. Some of the Native Peoples see the workings of Marxist ideology as leading to a super industrialized world in which the worst effects of industrial capitalism, which they see already destroying the world, are made to move even faster and more efficiently.

There are some strong arguments in the defense of Marxism, and some weak ones. The argument that Marxism is the only kind of organized resistance to capitalism that has ever worked does not appear to stand the test of history. Most successful revolutions in this century have been nationalist in nature and not class struggles of the type envisioned by Marxist ideology. It is probably more correct, however, that in some of the industrialized countries, especially western Europe, Marxist critiques of capitalism and the organization of the workers are necessary steps in the development of movements that may free peoples. It is also true that Marxism has many faces, and Native Peoples’ movement can find many allies among workers’ groups and organizations. The two movements have greatly different ideologies, histories, and different goals and objectives, but there are many Marxist tendencies that are truly anti-colonial in theory. There are also some Marxist tendencies, or at least tendencies that call themselves Marxist, that reject the hierarchical structure that has characterized Marxist history. The Native Peoples’ movements are not and should not be engaged in an ideological war with all of these Marxist tendencies.

The movements of Native Peoples and Marxism are two separate and distinct ideologies. In many aspects, Marxism and these movements conflict in ideology. The Native Peoples’ movement will, hopefully, develop a well-articulated and published ideology at some point during the ensuing decades, and there could well develop an intellectual tradition that could be studied and shared among many peoples. Marxism has never been critiqued from a perspective that is truly external to the objectives of Western ideologies. The first responses of Marxists has been to fall back on old and tried answers that were applicable in response to capitalist criticisms but that misinterpret the source of criticisms from what the Marxist language calls the third world. The debate, one might say, has barely begun. The struggle, however, continues.

There are also some strong arguments in criticism of the Native Peoples’ movements. Foremost among those arguments is the observation that there presently exists no published tradition that really represents this ideology. This lack of a published ideology makes it very difficult for the movement to acquire adherents, since there seem to be no recognized philosophers whose work can be used as a teaching and study tool. In fact, this problem is so significant that even to speak of a Native Peoples movement and its principles requires that one invent the term for the purpose. This lack of a recognized published ideology leaves the Native Peoples open to unfair criticisms that are not based on any real intellectual history. For example, critics of the movement state that Native peoples tend to idealize the past, and that they are not sensitive to current realities. Some of those criticisms are indicative of the critics, especially those who see Native Peoples as entirely historical beings. There is some resistance by contemporary European writers to accept the concept and reality that Native peoples and philosophers exist in the twentieth century, a bias that is shared by both conservatives and the modern Left. There is also a tendency on the part of critics to assume that a Native peoples’ movement must be romanticist in nature without any real effort to analyze and compare these movements. There may be tendencies within Native movements that have some romanticist tendencies, but writers within the movement to be critical of romanticism.

There is also a tendency to on the part of modern critics to see Native movements as anti-scientific and anti-intellectual. Thus Native movements are stereotyped in ways that would be immediately challenged were they applied to other movements, but go unchallenged by a Native community that has no identifiable body of intellectual thought. It is a weakness that Native Peoples’ movements need to address.

Finally, too often Native Peoples’ movements try too hard to disassociate themselves from all other forms of political ideology. There is an effort on the part of some Native Peoples to try to be absolutely unique, and to eschew any connection whatever with any other analysis or tool of analysis other than that developed by themselves. There appear to be substantial areas of Marxist thought in the critique of capitalism that should be useful to the Native movement, and there is a kind of progressive humanism that surfaces in the writings of many current writers on the history and development of technology and political economy that can serve to move Native interests forward. There is nothing contradictory about Native people seeking and finding allies within the camps of the ideologies of other peoples, and there is little doubt that social change, were such to take place in the West, would produce ideologies and movements that could complement the objectives of Native Peoples. There is nothing in the annals of history to prove that Marxists cannot acquire some kind of spiritual awareness (even if it is not religion) and that Native Peoples cannot develop or adopt forms of acceptable technologies that meet their needs in the context of their current realities. In fact, these kinds of things must happen.

Also

The Red Path and Socialism, by ᐊᓯᓂ Vern Harper (1979)

Marxism and Native Americans, reviewed by Howard Adams (1984)