Graffiti in Vancouver, BC, (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, Səl̓ílwətaʔ and xʷməθkʷəy̓əm territories), 2008

by M.Gouldhawke (âpihtawikosisân)

First published January 6, 2022, minor edits for readability Oct. 8, 2022

Anna Mae Pictou Aquash (also known as Naguset Eask and Annie Mae) was born in 1945 into the Mi’kmaq community of Indian Brook (part of the Sipekneꞌkatik First Nation, formerly Shubenacadie) in Nova Scotia.

She went on to become one of the most skilled warriors and dedicated community organizers in the Indigenous resistance movement, and because of this was targeted for repression by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

In 1976, she was found to have been murdered, after the FBI and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) initially tried to cover-up her true cause of death and identity.

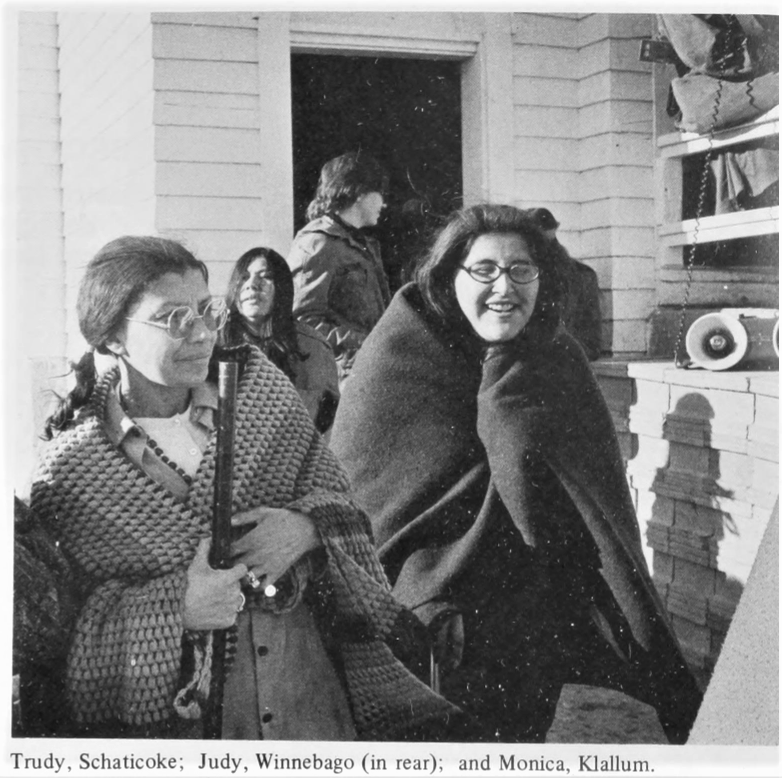

Pictou Aquash had taken part in many of the major Red Power actions of the 1970s, including the occupations of the Mayflower II in Boston in 1970, the BIA headquarters in Washington DC at the culmination of the Trail of Broken Treaties in 1972, Wounded Knee in 1973, Anicinabe Park in Ontario in 1974, and the Alexian Brothers’ Novitiate in Wisconsin in 1975.

“Anna Mae returned from her experience in the Washington portion of the Trail of Broken Treaties a renewed woman, dedicated and determined to share in the hemispheric struggle of Native Americans,” explained Shirley Hill Witt of Akwesasne, a co-founder of the National Indian Youth Council.

Throughout the 1970s, Pictou Aquash also trained in karate, did extensive fundraising work, created programs for the Red Schoolhouse (an American Indian Movement Survival School in St. Paul, Minnesota), and re-organized the Los Angeles AIM chapter.

Prior to the Trail of Broken Treaties in 1972, she had worked with the Boston Indian Council, at a day care, and briefly on the assembly line at a General Motors plant in the Greater Boston area.

Police Coverup

On February 24, 1976, Pictou Aquash’s body was found by a white rancher at the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota.

The FBI and BIA police at first tried to cover-up not only Pictou Aquash’s true cause of death, despite an obvious gunshot wound, but also her identity, having her quickly buried at Pine Ridge without documentation, before the FBI lab in Washington DC was able to identify her through fingerprint analysis from her severed hands that had been shipped to them from Pine Ridge.

“The police said that she had died of exposure,” despite there being a bullet in her head, wrote Mary Brave Bird (formerly Crow Dog) in her 1990 book, Lakota Woman.

Author and journalist Richard Wagamese noted as suspicious the circumstances under which “none of the officers present at the death scene was able to identify the victim even though Anna Mae was on the FBI’s most wanted list for her American Indian Movement (AIM) activities at that time.”

“To the FBI she was an agitator,” Wagamese explained, “to the Indians she was the first of a line of strong, dedicated female activists who emerged following Wounded Knee.”

Reign of Terror

Pine Ridge in the 1970s was the site of a reign of terror involving dozens of murders and assaults carried out by reservation BIA police officers and an associated vigilante group who called themselves the Guardians of the Oglala Nation, the Goons.

The Goons were led by Tribal Chairman Dick Wilson and in fact included some BIA cops. They were also backed by the FBI, who supplied them with information and ammunition to use against other Lakota people, as well as against AIM members and associates.

The BIA, after their fraudulent autopsy of Pictou Aquash’s body, tried to prevent people at Pine Ridge from viewing and possibly identifying her. They then proceeded to bury her on March 2, 1976, without a death certificate or burial permit, before the FBI in Washington DC announced on March 6 that they had identified her by fingerprint analysis.

Reservation police chief Ken Sayres had arranged funding for the burial and claimed decomposition as the reason for carrying it out before Pictou Aquash had been identified, according to Johanna Brand, author of the 1978 book, The Life and Death of Anna Mae Aquash.

The Holy Rosary Mission at Pine Ridge was the only church that would agree to perform the task without the usual documentation, and they kept no records of it.

Once Pictou Aquash had been identified, her family requested a second autopsy with a non-BIA pathologist, an autopsy which then revealed the murder that the FBI, BIA and reservation police had tried to conceal.

“Now, an embarrassed and exposed FBI is trying to cover its tracks,” reported the Akwesasne Notes newspaper in their Early Spring, 1976 issue.

Mary Lafford, one of Pictou Aquash’s sisters, later said in the 1979 documentary film, Annie Mae – Brave Hearted Woman, that when the FBI called her and told her they’d identified her sister as the victim, they simply said she’d died of exposure.

“That’s all they said,” explained Lafford, “no ‘I’m sorry’ or anything like that, just a blunt thing.”

As Lafford put it, “The whole thing is foolish to me anyway, to start off with, the investigations are done by the FBI and they’re the ones involved.”

“What can I say?”, Lafford asked in dismay, “You’re investigating yourself?”

According to author Johanna Brand, police chief Ken Sayres later fraudulently denied that he and FBI agent David Price were present when Pictou Aquash’s body was found. Agent Price was familiar with Pictou Aquash, having previously arrested, interrogated and threatened her.

Pattern of Violence

In the years prior to Pictou Aquash’s murder, several alleged killings of Indigenous women by Goons at Pine Ridge had also been passed off by authorities and their pathologist as death from exposure, as in the cases of Lena R. Slow Bear, Elaine Wagner, and Delphine Crow Dog.

In March of 1975, an unknown sniper, to this day still never identified by police, shot and killed Jeanette Marie Bissonette, a mother of six, just north of Pine Ridge, after she got a flat tire as she was driving home from a wake. She had pulled over across the road from Tribal Chairman Dick Wilson’s country home, according to the Akwesasne Notes newspaper.

Jeanette Marie Bissonette’s brother-in-law, Pedro Bissonette, executive director of the Oglala Sioux Civil Rights Organization (OSCRO), had previously been shot and killed by a BIA police officer in 1973, just following the re-occupation of Wounded Knee.

Several alleged killings by Goons at Pine Ridge were also carried out in the months leading up to and after February of 1976 (when Pictou Aquash’s body was found), as in the cases of Hilda Rose Good Buffalo, Janice Black Bear, Lydla Cut Grass, Betty Lou Means and Byron DeSersa.

In February of 1975, Goons even physically assaulted a legal team, the Wounded Knee Legal Defense/Offense Committee, at the Pine Ridge airport, with Tribal Chairman Dick Wilson present. According to an affidavit by paralegal Eda Gordon, who was threatened and slightly injured by a Goon with a knife, Wilson told his Goons, “I want you to stomp ’em.”

Goon and BIA cop Paul Duane Herman Jr. was one of the officers present when Pictou Aquash’s body was found in February of 1976. Just a few months later, Herman Jr. shot and killed 15-year-old Sandra Ellen Wounded Foot at Pine Ridge. Upon pleading guilty to ‘voluntary manslaughter’, he was sentenced to only 10 years in prison.

Goon leader Duane Brewer later admitted in an interview with journalist Kevin McKiernan that there was strong evidence linking Herman Jr. to Pictou Aquash’s murder as well. Instead of following this evidence, the FBI decided to shift the blame from themselves, the BIA and the Goons onto AIM.

Police Perspective

In Kevin McKiernan’s 1990 documentary film, The Spirit of Crazy Horse, Duane Brewer admitted to being given armor-piercing ammunition by the FBI for use against AIM and other Lakota people during the 1970s reign of terror.

When asked how he could justify the Goons having done drive-by shootings of homes on the reservation, Brewer admitted, “you really can’t, we just got away with it.”

In the mainstream media at the time of the reign of terror, Tribal Chairman Dick Wilson and South Dakota Attorney General William Janklow even publicly endorsed shooting AIM members.

In a Rolling Stone magazine article from 1977 on the Pictou Aquash case, Norman Zigrossi, the FBI deputy commander in Rapid City, said, “they’re a conquered nation, and when you are conquered, the people you are conquered by dictate your future… [the FBI] must function as a colonial police force.”

Police Story

Author Johanna Brand pointed out in her book that the FBI supplied their version of Pictou Aquash’s murder to the Rapid City Journal, “on March 11 [of 1976], before the results of the second autopsy were known.”

As Brand explained, “a story appeared in the Rapid City Journal, captioned ‘FBI Denies AIM Implication That Aquash Was Informant.'”

“In this way,” clarified Brand, “the Bureau, responding publicly to charges that AIM had not made public, set the stage for its interpretation of a murder that had not yet been officially discovered.”

According to Brand, Pictou Aquash didn’t fit the profile of an FBI infiltrator or informer, and whatever rumours may have existed about her to that effect were thought by some AIM members to have been started by an actual FBI infiltrator and Goon, John Stewart.

“Whatever the accusation against her, Anna Mae never acted according to the usual informer pattern,” wrote Brand.

“It was more common for a spy to be an unobtrusive person on the periphery of AIM or, if active, a disruptive force.”

“Anna Mae Aquash was neither,” Brand pointed out, because “the work she did undoubtedly benefited AIM and the accusations against her were based entirely on speculation.”

According to author Peter Matthiessen, and his book, In The Spirit of Crazy Horse, Pictou Aquash had in fact been “one of the first AIM people to suspect that Douglas Durham was some sort of government agent,” with Durham later turning out to be the highest-level state infiltrator to ever be exposed within AIM, having been the organization’s head of security.

Pictou Aquash, while re-organizing the Los Angeles chapter of AIM, had even complained about Durham to AIM’s national office in St. Paul, Minnesota, only to be told that he had been sent there because of his disruptive activity, and that she should keep an eye on him.

Investigating the Investigators

The Oakland-based newspaper, The Black Panther, in March of 1976 reported on Pictou Aquash’s murder, with the subheading, “Foul Play by FBI Suspected.”

The article included part of a statement from traditional leaders at Oglala, Pine Ridge, which read, “The way in which the BlA police and the Federal Bureau of Investigation have handled this investigation makes it appear more of a coverup than an investigation of still another Indian killed on the Pine Ridge Reservation.”

“We want to know the truth about Anna Mae’s death and the possibility of the government’s involvement in it,” the Oglala leaders stated.

Also in March of 1976, Shirley Hill Witt, then working with a regional office of the US Commission on Civil Rights, wrote to the staff director for the Commission about the murders of Byron DeSersa and Anna Mae Pictou Aquash, saying, “there is sufficient credibility in reports reaching this office to cast doubt on the propriety of actions by the FBI, and to raise questions about their impartiality and the focus of their concern.”

In May of 1976, the Native Council of Canada were reported as saying they’d been unsuccessful up to that point in getting the Canadian government to ask their US counterparts to investigate the BIA and FBI’s handling of the Pictou Aquash case.

Gloria George, then president of the organization, was in the Globe and Mail‘s wording reported as saying “pressure for an investigation came because some people at Wounded Knee think she [Pictou Aquash] may have been killed by FBI agents or Bureau of Indian Affairs police because of her involvement with AIM members.”

Duke Redbird, the organization’s vice president said that they were upset about the “discrepancy in reported causes of death, the mutilation of her body and the disrespect shown her family, who were not informed of her death for nine days.”

Real People

Mary Lafford, Pictou Aquash’s sister, wrote the afterword to Johanna Brand’s 1978 biography of her sister.

Lafford explained that she believed that the person or persons involved in her sister’s murder may be connected with the FBI, either directly or indirectly, and that their identities may never be found.

Given how powerful the FBI are, her sister couldn’t have hurt them. So killing her was the result of ignorance on the part of her killers, Lafford argued.

Her sister was an educated person who also had common sense, and she worked for AIM out of dedication, not out of interest in publicity or headlines.

“The real Indian people” like her sister should be in control of the movement, stated Lafford.

In a Rolling Stone magazine article from 1977, Lafford was quoted as saying that her sister had called her on the phone in late 1975 and spoken in the Mi’kmaq language in order to subvert police surveillance.

Lafford explained that her sister said the FBI thought she had information on who had killed two FBI agents in a shootout at Oglala, Pine Ridge on June 26, 1975, that they would arrest her again, and that sooner or later she would be shot. Pictou Aquash asked Lafford to raise her children if anything should happen to her.

Jim Maloney, Pictou Aquash’s ex-husband, had custody of her children. He would go on to work extensively in training police officers, including with the RCMP and at the New Hampshire Lethal Force Institute, where, according to the Ottawa Citizen in 1986, he was “teaching Americans handy tricks like how to kill people with small knives.”

Pictou Aquash had initially broken up with Maloney back in Boston, after he had an affair with a white woman at his karate school.

In a letter from 1974, read aloud by her sister Rebecca Julian in the documentary Annie Mae – Brave Hearted Woman, Pictou Aquash explains that Maloney had taken her children away because she went to Wounded Knee.

“He turned out to be such a sell-out,” wrote Pictou Aquash.

Cop Code

In 1978, W.H. Kelly, a retired deputy commissioner of the RCMP, wrote a book review for the Ottawa Citizen of The Life and Death of Anna Mae Aquash, claiming that the author Johanna Brand was “biased for the Indians… [and] ignores the other side,” by which he meant the side of the police, FBI and RCMP.

Kelly claimed that the RCMP’s surveillance of AIM and coordination with the FBI had been “normal.”

He also justified the FBI and BIA’s handling of the Pictou Aquash case, disparaging Brand’s book as a “subjective study.”

According to Brand, RCMP officials had opened a file on Pictou Aquash after the June 26, 1975 shootout at Oglala, Pine Ridge, and wanted to bring her in for questioning, as well as question her family on her whereabouts.

Deborah Maloney, one of Pictou Aquash’s two daughters, went on to become an RCMP officer, eventually achieving the rank of corporal.

In 1993, Maloney took part in an RCMP press conference where she claimed that fellow officers of South Asian ancestry were lying when they filed a human rights complaint about being subjected to racism within the force.

“I want the general public to know that they have a good police force,” Maloney said.

A few years later, officer Maloney took part in a September 16, 1999, press conference in Ottawa, where a former AIM associate was named and blamed for her mother’s murder, rather than the BIA and its police, who had tried to coverup Pictou Aquash’s identity and true cause of death, and who had killed many other Indigenous women on the same reservation during the same time period.

The Ottawa Citizen declined to print the name of the accused, since this was prior to any criminal charges being laid.

Less than a month later, on November 3, so-called ‘Autonomous’ AIM chapter members Russell Means and Ward Churchill took part in a similar press conference in Denver, Colorado, accusing AIM associates of involvement in Pictou Aquash’s murder and calling for a grand jury to be convened against them. Churchill, as an academic, subsequently regurgitated the police version of events in his writing.

Jails Are Not a Solution to Problems

In an interview after an arrest in 1975, Pictou Aquash stated, “Jails are not a solution to problems… the FBI certainly conducted themselves with the attitude that they are racist.”

On December 17, 2021, Canada’s Correctional Investigator, Dr. Ivan Zinger, released data showing that the disproportionate incarceration of Indigenous women in Canada has been increasing over the past ten years, while that of non-Indigenous women had been decreasing, so that soon half of the women in federal prisons will be Indigenous.

Incarceration of Indigenous women in some Canadian provincial prisons is even more disproportionate, as high as 90% at the Pine Grove Correctional Centre in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan.

Pictou Aquash, after another arrest in 1975, wrote a letter to her sister Rebecca Julian, saying that her “efforts to raise the consciousness of whites that are so against Indians here in the United States were bound to be stopped by the FBI… These white people think the country belongs to them…”

Although repeatedly arrested, interrogated and threatened by FBI agents, Pictou Aquash refused to cooperate with them against fellow AIM members.

AIM organizer Leonard Peltier, during his 1977 trial over the June 26, 1975, shootout at Oglala, Pine Ridge, spoke out on what he called Pictou Aquash’s “cold-blooded murder,” asking the court, “who is going to pay for Anna Mae’s death?… What about the Gestapo tactics being used on the Pine Ridge residents?”

Peltier also later wrote of Pictou Aquash’s murder and her treatment by the FBI in his 1999 book, Prison Writings: My Life is My Sundance.

In 1977, Myrtle Poor Bear of Pine Ridge signed an affidavit and testified that FBI agents used Pictou Aquash’s killing as a threat and means of intimidation against her, to get her to sign an affidavit against Peltier.

In Pictou Aquash’s statement to the Court of South Dakota in 1975, which was subsequently published, she placed FBI repression within its full context of attacks on various social movements by the Bureau, as she asked the people who would later read her words to “help us free Leonard Peltier.”

Waiving the Law

In the 1990s and 2000s, Robert Ecoffey, a former Pine Ridge BIA cop turned US Marshal, who had testified against Peltier at trial and had been present at the shootout that led to that case, worked with other police officers and the FBI to fabricate a case and charges against former AIM associates for the murder of Pictou Aquash.

Subsequently, Fritz Arlo Looking Cloud was found guilty of federal murder in 2004, Richard Marshall was acquitted of a weapons charge in 2010, and Thelma Rios pleaded guilty to kidnapping that same year.

In Looking Cloud’s trial, the government’s attorney admitted that his testimony was unreliable, that Looking Cloud “tells whatever story he thinks is going to sound best to whoever he is telling it to.”

However, this did not stop the government from subsequently using Looking Cloud to prosecute others.

Kamook (Darlene) Ecoffey, a paid police informant, married to law enforcement officer Robert Ecoffey, wore a wire and recorded a conversation with Looking Cloud where she advised him to place blame on John Graham, a Southern Tutchone man from the Yukon.

In 2011, Graham was found not guilty on a charge of premeditated murder, but was found guilty of a felony kidnapping-murder charge, a guilt-by-association charge that doesn’t exist under Canadian law.

The only conviction-relevant evidence presented by the prosecution in Graham’s case, even according to the prosecution themselves, was contradictory and police-incentivized testimony by presumed accomplices to the crimes, not physical evidence.

It was later discovered that the Canadian Justice Minister in 2010 had privately waived a breach of the extradition treaty with the US in order to allow Graham to be prosecuted in the US on the guilt-by-association charge that doesn’t exist under Canadian law, the equivalent of which had been previously declared unconstitutional in Canada.

In an assessment of the Graham case from 1998, US Attorney Karen Schreier had written that besides problems of jurisdiction, “another potential downside to federal prosecution of the case is that it may be seen as a coverup.”

“Over the years, numerous individuals have alleged that the victim was either killed by the FBI or was killed as a result of FBI actions,” explained Schreier.

“Prosecution of members of the American Indian Movement for the homicide could be seen as an effort on the part of the federal government to hide the role of the FBI in Aquash’s death,” Schreier noted.

Brave Hearted Women

In an interview about her arrest by the FBI in September of 1975, Pictou Aquash stated, “I think that they [the FBI] most definitely want to destroy the Indian Nation if it will not submit to the living conditions of a so-called reservation.”

“They definitely are out to destroy our concept of freedom,” she further explained.

The Boston Indian Council, after Pictou Aquash’s death, paid tribute to her in their newsletter, writing that she was a “woman of courage, of dignity, and of pride,” and that without her, their organization “would never have been possible.”

The newspaper Akwesasne Notes pointed out that one of Pictou Aquash’s dreams “was to establish a People’s History of the Land, with research teams all over the continent scouring libraries and newspaper clippings and the memories of local people for information on the true story of Native nations.”

Mary Brave Bird wrote in 1990 that “Annie Mae taught me a lot.”

“Wherever Indians fought for their rights, Annie Mae was there,” Brave Bird explained.

In the 1979 documentary film, Annie Mae – Brave Hearted Woman, a group of Pine Ridge women discussed Pictou Aquash in a positive light, with one woman saying, “she wasn’t no informer, and everybody knew that.”

In 2005, renowned Stó:lō/Métis writer and organizer Lee Maracle, in a support letter for her friend John Graham, criticized the men in the leadership of AIM, but strongly contrasted Graham to them, writing that “he taught me to respect myself as a woman, as a mother and as a First Nations person… I can’t believe they have selected John Graham as the patsy for this murder.”

Maracle was in fact one of many Indigenous women, including elders and women in the Native Youth Movement, who spoke out in support of John Graham and against the FBI’s attempt to coverup the reign of terror at Pine Ridge in the 1970s.

In 2006, Billie Pierre, co-founder of Redwire Magazine, wrote that “in the past few years, the memory of Anna Mae Pictou-Aquash — an American Indian Movement (AIM) leader from the Mi’kmaq Nation in Nova Scotia, Canada — has been reduced to that of a helpless woman who was murdered by her own allies.”

“In reality, her murder is part of a ruthless campaign waged by the US government — a campaign that, far from being ancient history, is still unfolding today,” explained Pierre.

Elwha Klallam tribal elder, Monica J. Charles (a veteran of the occupations of the BIA in 1972 and Wounded Knee in 1973) wrote in 2007 that Pictou Aquash was not simply a victim, but “was a strong, intelligent Indian woman that lived her life in service to Indian People.”

“The United States Government has no concrete evidence against John [Graham] to warrant his extradition to South Dakota.”

“We will not give up any more of our People to cover up crimes committed against us,” wrote Charles.

Colonial Cops

Contrary to RCMP officer Deborah Maloney’s claim about a “good police force” that is devoid of racism, the RCMP is in actuality a colonial police force, specifically designed to steal land and repress Indigenous culture.

In 2021, RCMP officers argued to a coroner’s inquest that their fellow officer Scott Hait was justified in shooting to death Rodney Levi of the Metepenagiag Mi’kmaq Nation the previous year.

The inquest jury recommended that the RCMP shouldn’t be first responders for mental health wellness checks, and that mandatory First Nations cultural sensitivity and awareness training should be implemented at the RCMP’s national training depot in Regina, Saskatchewan (which happens to be the site of the 1885 hanging of Métis leader Louis Riel for treason).

In 2020, RCMP officers stood idly by and allowed white fishermen to vandalize and torch Sipekneꞌkatik lobster facilities and vehicles. Afterwards, RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki publicly defended her officers conduct.

In 2019, the Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls stated that “the RCMP have not proven to Canada that they are capable of holding themselves to account – and, in fact, many of the truths shared here speak to ongoing issues of systemic and individual racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination that prevent honest oversight from taking place.”

At Elsipogtog in 2013 and Burnt Church in the early 2000s, the RCMP were deployed to repress Mi’kmaq sovereignty struggles.

In 1989, the Royal Commission on the Donald Marshall Jr. Prosecution found fault with certain RCMP officers regarding their re-investigation of his case.

Donald Marshall Jr. was a Mi’kmaq man from the Membertou community, wrongfully sentenced to life imprisonment for the murder of his acquaintance Sandy Seale in 1971, after an investigation by municipal police that let the actual killer, Roy Ebsary, go free, and which led to Marshall Jr. spending 11 years in prison for Ebsary’s actions.

The Royal Commission found that after Marshall Jr.’s conviction, RCMP Inspector Alan Marshall, in his own words, had “botched” his investigation of new allegations that could have sooner uncovered the true facts of the case.

Furthermore, the Royal Commission found that RCMP officers Harry Wheaton and James Carroll, when re-investigating the case in 1982, “were initially skeptical of Marshall’s innocence,” were “blinded” by their own assumptions, and secured a statement from him while he was in prison that “was used to devastating effect against him during the later Court of Appeal Reference hearing.”

Clearly the RCMP, FBI and other cops can only be trusted to cover for each other and to continue to repress Indigenous sovereignty, not to uncover their own crimes against Indigenous peoples.

In a statement to the Court of South Dakota in September of 1975, Anna Mae Pictou Aquash explained, “They want us to continue to give respect and validity to their forms of power, their laws and their guns and their bombs.”

“They do not want us to ever recognize that these things are not things of power, these are tools of repression.”

Voices from Wounded Knee, 1973, by Akwesasne Notes (1974)

Sources

Jails are not a solution to problems, by Anna Mae Pictou Aquash (1975)

Anna Mae Pictou Aquash in her own words (1975)

Chronology of Oppression at Pine Ridge (1977)

The Brave-Hearted Women: The Struggle at Wounded Knee, by Shirley Hill Witt, 1976

Pine Ridge warrior treated as ‘just another dead Indian‘, by Richard Wagamese, 1990

Lakota Woman, by Mary Crow Dog, 1990

The Life and Death of Anna Mae Aquash, by Johanna Brand, 1978

Akwesasne Notes, Volume 8, Number 1, early spring 1976

Annie Mae – Brave Hearted Woman, a documentary film from 1979 by Lan Brookes Ritz

The Killing of Anna Mae Aquash, Rolling Stone, April 7, 1977

Akwesasne Notes, Volume 7, Number 2, early summer 1975

The Spirit of Crazy Horse, a PBS documentary film by Kevin McKiernan, 1990

Death Squads in the US: Confessions of a Government Terrorist, by Ward Churchill, Yale Journal of Law and Liberation, 1992 (based on a transcript of Kevin McKiernan’s full interview of Duane Brewer for the making of the 1990 documentary, The Spirit of Crazy Horse)

In the Spirit of Crazy Horse, by Peter Matthiessen, 1983

The Black Panther, March 27, 1976

Report on Federal, State, and Tribal Jurisdiction: Final Report to the American Indian Policy Review Commission, 1976

Canadian woman killed in U.S., Bid to have Indian’s death probed fail, Globe and Mail, May 14, 1976

Fighting Terror: That’s the aim of rural N.S. training camp, Ottawa Citizen, September 20, 1986

Passion colors study of an activist’s death, Ottawa Citizen, July 22, 1978

Racism absent in RCMP, six non-white officers say, Vancouver Sun, March 4, 1993

Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019

Aquash’s family fingers ‘trigger man’, Ottawa Citizen, September 17, 1999

Leonard Peltier’s Trial Statements Regarding Anna Mae Pictou Aquash (1977)

Leonard Peltier, Prison Writings: My Life is My Sun Dance, 1999

Trial Brief by Vine Richard Marshall (Hanna, Dana) (Entered: 01/27/2009)

Ghost Dancers return to haunt B.C. Supreme Court, Vancouver Sun, October 1, 2019

Lee Maracle’s Support Letter for John Graham (2005)

US Renews War on the American Indian Movement: The Anna Mae Pictou-Aquash Story,

by Billie Pierre, Earth First! Journal, January/February 2006

Women with the Native Youth Movement of Vancouver show support for Anna Mae Pictou Aquash, Leonard Peltier and John Graham, outside the BC Supreme Court in Vancouver (March 1, 2004)

Women with the Native Youth Movement of Vancouver show support for Anna Mae Pictou Aquash, Leonard Peltier and John Graham, outside the BC Supreme Court in Vancouver (March 1, 2004)

Also

Indian Activist Killed: Body Found on Pine Ridge, by Candy Hamilton (1976)

Anna Mae Lived and Died For All of Us, by the Boston Indian Council (1976)

Repression on Pine Ridge, by the Amherst Native American Solidarity Committee (1976)

Review of ‘The Life and Death of Anna Mae Aquash’, by Akwesasne Notes (1978)

Anna Mae Aquash, Indian Warrior, by Susan Van Gelder (1979)

Indian Activist’s Bold Life on Film, by John Tuvo (1980)

Poem for Nana, by June Jordan (1980)

Leonard Peltier Regarding the Anna Mae Pictou Aquash Investigation (1999-2007)

Free John Graham – Honour Anna Mae Aquash | PDF

A Report on the Case of Anna Mae Pictou Aquash, by Zig-Zag | PDF

Is the Crown at war with us? (2002)

Feds to re-examine Pine Ridge cases, by Kristi Eaton (2012)

A Concise Chronology of Canada’s Colonial Cops, by M.Gouldhawke (2020)

International Leonard Peltier Defense Committee

Further reading

Voices from Wounded Knee, 1973, by Akwesasne Notes (1974)

Like a Hurricane: The Indian Movement from Alcatraz to Wounded Knee, by Paul Chaat Smith and Robert Allen Warrior (1996)

The Trial of Leonard Peltier, by Jim Messerschmidt (1983)

Documentary about the re-occupation of Wounded Knee 1973 and AIM