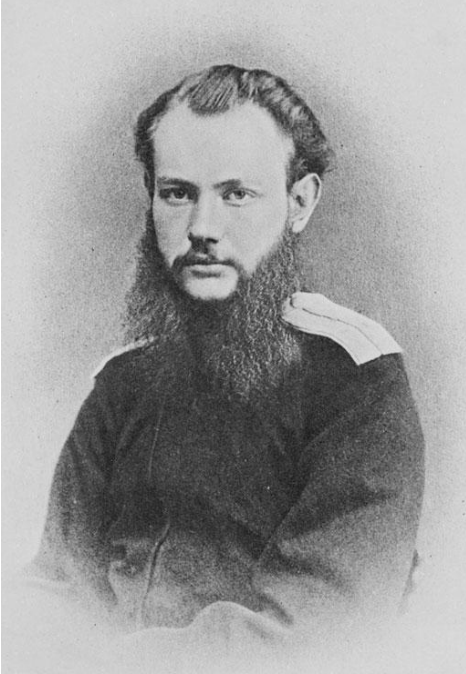

From ‘Les Temps Nouveaux’, 27 April 1912, translated by Paul Sharkey, republished by the Black Flag Anarchist Review, Autumn 2022

There is a quite serious revolutionary movement among the peasants in northern Mexico, and the republican government is unable to master it.

There are expropriations of landlords by the Indian farmers there. From time to time there have been battles fought and Regeneración is not alone in mentioning these battles. From Los Angeles I have been sent several Mexican newspapers of varying opinions with the passages marked that relate to the encounters between government troops and the “insurgents” and this is happening all the time and it is not always the former who come off best in the fighting.

“Skirmishes” might be a more appropriate term for these encounters, as the word “battle” should be used for encounters between larger forces. But it would be an absolutely false idea of what all agrarian movements are, including those of July-August 1789, not to see that the movement in northern Mexico has the character that all peasant movements have always had.

This, for me, explains why some friends are disillusioned about the “Mexican revolution”. Like so many other Italian, Russian, etc., etc., friends, they have probably dreamt of Garibaldian campaigns and found nothing like it. Peaceful plains, countryside, wary (and with good reason) of strangers and — from time to time — sometimes here, sometimes twenty leagues east, south or north of that point, seven, eight days away, another village drives out the exploiters and seizes the land. Then, twenty, thirty days later, a detachment of soldiers “of order” arrive; they execute rebels, torch the village, and at the moment they head back “victorious”, they march into an ambush from which they escape only by leaving half the detachment dead or wounded.

This is what a peasant movement is. And it is obvious that if young people dreaming of a Garibaldian campaign arrive there, full of military zeal, they found only disappointment. They quickly realized their uselessness.

Unfortunately, nine tenths (perhaps ninety-nine hundredths) of anarchists cannot conceive of “revolution” other than in the form of battles on barricades, or triumphant Garibaldian expeditions.

I imagine the disappointment of young Italians or French understanding “the revolution” through the books and poems of bourgeois revolutionaries had they turned up in 1904 during the peasant uprisings in Russia. They would have returned “disgusted”, those who dreamt of battles, bayonet charges and all the warlike trappings of the Expedition of the Thousand.

And yet today we have a detailed account of this movement — about which social democrats and anarchists had no idea, and which none of them supported, in any way (“Wait for the signal for a general uprising”, these intellectuals told them), now that we have documented investigations into this movement, we see what immense importance it had for the development of the revolutionary movement of 1905 and 1906.

But so what? Would they not have had the same disappointments if they had turned up in Siberia when 3,000 kilometres of the Trans-Siberian [railway] were on strike and the Strike Committee, negotiating as equals with Linevitch, the commander of an army of five hundred thousand men, made a superb effort to bring one-hundred-and-fifty thousand men home in one month.

And — for us — that unarmed strike, that expropriation of the State (which owned the railways), that spontaneous organisation of thousands of railway workers across several thousand kilometres, was it not a formidable object lesson — which to this day no anarchist has yet told the French workers in all its simplicity and all its prophetic significance — just as no one has yet told the story of the 1789–1793 peasant, in all its innermost simplicity, without cocked military caps [képis], without red sashes, but more effective than caps and sashes.

P. Kropotkin

Also

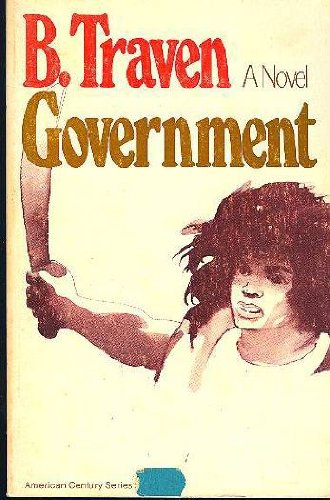

Black Flag Anarchist Review (Autumn 2022)

A debate on the Mexican Revolution in Temps Nouveaux, translated by Paul Sharkey

The Mexican Revolution, by Voltairine de Cleyre (1911)

How to Survive in the Jungle, by James Herndon (1971)

The Conquest of Bread, by Peter Kropotkin (introduction by Alfredo M. Bonanno)

Kropotkin texts at the Anarchist Library

Anarchists on National Liberation

Anarchism & Indigenous Peoples