by M.Gouldhawke, revised April 12, 2023, originally published September 3, 2022

Guillaume-François Le Trosne was a French jurist and political economist of the Physiocrat school of economics, and one of the many influences on the notorious communist thinker Karl Marx.

Le Trosne’s book, On the Social Interest (Regarding the relation of Value to Circulation, Industry, and Internal and External Commerce) was first published in 1777. Its title page advertised the book as being, in part, a polemic against the philosopher and dabbler in economics, Étienne Bonnot Abbé de Condillac.

Several decades later, Marx developed a general interest in the Physiocrat school of economics, but may have been particularly interested in Le Trosne’s background as a student of law, as Marx had also once been, and as a writer who placed polemics prominently in his approach, as Marx did too throughout his own writing career.

Marx, in his own book, Capital Volume 1, first published in 1867, even complimented Le Trosne on his polemic against Condillac, which concerned the character of production for exchange, with exchange on its own not being a means to increase value.

In Capital, Marx also criticized the political economist Jean-Baptiste Say for having “exploited the writings of the Physiocrats,” more specifically Le Trosne’s phrase “Products can only be paid for with products.”

Uncharacteristically, Marx never specifically critiqued Le Trosne’s views, unlike how he treated basically all other political economists or other kinds of thinkers, including David Ricardo and Adam Smith. However, Marx did both critique and praise different aspects of the thinking of the wider Physiocrat school to which Le Trosne belonged.

Furthermore, Marx referenced Le Trosne a baker’s dozen times in the footnotes to the first eight chapters of Capital Volume 1 (in the English and French editions, corresponding to the first six chapters of the second to fourth German editions, or the first three chapters of the first German edition). This added up to more distinct references to Le Trosne in this foundational part of the book than Marx made to Ricardo or Smith, who are more likely to be seen as his major influences in terms of a supposed “Labour Theory of Value“, which neither Marx nor Le Trosne actually held.1

Footnotes and Quotes

Marx’s first reference to and quotation of Le Trosne in Capital related to the definition of exchange-value.

Le Trosne, in this case, having written that “Value consists of the exchange relation between one thing and another, between the amount of one product and that of another,”

Le Trosne’s follow-up sentence in The Social Interest, which was not quoted or referenced in Capital by Marx, superficially touched on the form of value. Le Trosne having written that “Price is the expression of value: it is not distinct in exchange, each thing is reciprocally the price of the commodity; in sale, the price is money.”

Marx’s next Le Trosne reference in Capital quoted his line that “Properly speaking, all products of the same kind form a single mass, and their price is determined in general and without regard to particular circumstances.”

Marx used this reference while introducing the category of socially necessary labour time, the determinant of the magnitude of value. Marx didn’t refer to Smith or Ricardo on this matter, but instead Le Trosne and an anonymous author whose book was published in either 1739 or 1740, prior to Smith and Ricardo’s works. “The individual commodity,” wrote Marx, “counts here only as an average sample of its kind.”2

Subsequently, Marx referenced and quoted Le Trosne’s line that “Money is not a mere symbol, for it is itself wealth; it does not represent values, it is their equivalent.”

As Marx himself explained, money is also a commodity, and “the money-form is merely the reflection thrown upon a single commodity by the relations between all the other commodities.”

“The fact,” wrote Marx, “that money can, in certain functions, be replaced by mere symbols of itself, gave rise to another mistaken notion, that it is itself a mere symbol.” 3

Next, Marx quoted Le Trosne on the equivalence of money and commodities, in relation to price. However, Marx also pointed out that although money and commodities are equivalents, and price is the expression of this, price can also diverge from the magnitude of value, and this is not a defect, but makes price the adequate form for “laws [that] can only assert themselves as blindly operating averages between constant irregularities.”4

Subsequently, Le Trosne was quoted as having described the exchange process as consisting of “four final terms and three contracting parties, one of whom intervenes twice.”

As Marx himself explained, the “complete metamorphosis” of one commodity starts when that commodity comes face to face with money and ends when that money is then used to purchase a different commodity. After receiving money, the first seller then becomes a buyer from a third commodity-owner, who is now the seller.

The exchange process of each commodity, which follows the path Commodity-Money-Commodity, is also “inextricably entwined with the circuits of other commodities.” The process of exchange consists of two acts of exchange, not just one, says Marx, while circulation involves the interrelated exchange processes of all commodities (including money).5

Marx next quoted Le Trosne’s statement that money “has no other motion than that with which it is endowed by the product.”

As Marx explained, “the situation appears to be the reverse of this, namely the circulation of commodities seems to be the result of the movement of money.” Le Trosne had seemingly seen through this.6

Marx’s subsequent reference to Le Trosne related to the “repeated change of place of the same pieces of money,” as Marx put it.7

Products set money in motion, according to Le Trosne, and when necessary, money moves from “hand to hand, without stopping for a moment.”

Next, Marx quoted Le Trosne’s line that “Money is shared among the nations in accordance with their need for it … as it is always attracted by the products.”

Then, Marx quoted Le Trosne as having written that “It is not the parties to a contract who decide on the value; that has been decided before the contract.”

Marx used this in order to bolster his own theory of the socially objective character of value, in relation to capital. “The value of a commodity,” Marx wrote, “is expressed in its price before it enters into circulation, and it is therefore a pre-condition of circulation, not its result.”

In exchange, Marx further explained, the same value remains in the hands of the same commodity-owner, and therefore, “disregarding circumstances which do not flow from the immanent laws of simple commodity circulation, all that happens in exchange (if we leave aside the replacing of one use-value by another) is a metamorphosis, a mere change in the form of the commodity.”8

Marx subsequently quoted Le Trosne’s statement that “some external circumstance” can lessen or increase a commodity’s price, but this change results from the circumstance and not from “the exchange itself.”

Marx immediately followed this reference with another to Le Trosne, quoting him as having written that “Exchange is by its nature a contract which rests on equality, i.e. it takes place between two equal values. It is therefore not a means of self-enrichment, since as much is given as is received.”

Next, as already mentioned, Marx noted the quality of Le Trosne’s polemic against Condillac, writing that “Le Trosne therefore answers his friend Condillac quite correctly as follows: ‘In a developed society absolutely nothing is superfluous.'”

Then, Marx referenced Le Trosne’s explanation that if a seller is compelled to sell their product at less than its value, say 18 dollars for what normally fetches 24 dollars, when it comes time to purchase, they will then be able to buy 24 dollars worth of commodities for only 18 dollars.

“The formation of surplus-value,” argued Marx, “and therefore the transformation of money into capital, can consequently be explained neither by assuming that commodities are sold above their value, nor by assuming that they are bought at less than their value. […] The capitalist class of a given country, taken as a whole, cannot defraud itself.”9

Next, as already mentioned, Marx lambasted Jean-Baptiste Say for having exploited Le Trosne’s line that “Products can only be paid for with products.”

Finally, Marx repeated the quote of Le Trosne’s already used in the first chapter of Capital Volume 1, this being that “all products of the same kind form a single mass, and their price is determined in general and without regard to particular circumstance.”

Marx wanted to emphasize that the value of a commodity is not set in stone after its production, because the labour-time socially necessary to reproduce another copy of the same kind of commodity is always subject to changing conditions.

“If the amount of labour-time socially necessary for the production of any commodity alters,” explained Marx, “and a given weight of cotton represents more labour after a bad harvest than after a good one — this reacts back on all the old commodities of the same type, because they are only individuals of the same species, and their value at any given time is measured by the labour socially necessary to produce them, i.e. by the labour necessary under the social conditions existing at the time.”10

Marx’s category of commodity “type”, “kind” or “species”, which owes at least a little something to Le Trosne, is often ignored by contemporary scholars of Marx.

What concerned Marx was not the incidental relation between two different kinds of use-values in a singular act of exchange, an act of barter between two people possessing different commodities. Rather, he was analyzing the commodity as a social relation involving all people in a capitalist society.

The commodity, on the one hand, as a social relation involving all commodities of the same type (which have the same value), and on the other, the communal expression of the value equivalence of all the different types of commodities in a single commodity type, money.

The communal value expression of all commodities in price, prior to their individual sale, and an exchange process which consists of two acts of exchange, not one. The complete metamorphosis of each commodity including parts of the circuits of transformation of two other commodities, all within the wider circulation of commodities in a capitalist society.

Structure of Presentation

Aside from these references and quotes, Marx seems to have been influenced by the chapter structure of Le Trosne’s book. He may have also been affected by Le Trosne’s extensive use of sub-chapters, something that wasn’t common in economic works at the time. Ricardo and Smith didn’t use them, for example, while political economist Samuel Bailey and philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel did deploy them in some of their books, but which were published after Le Trosne’s.11

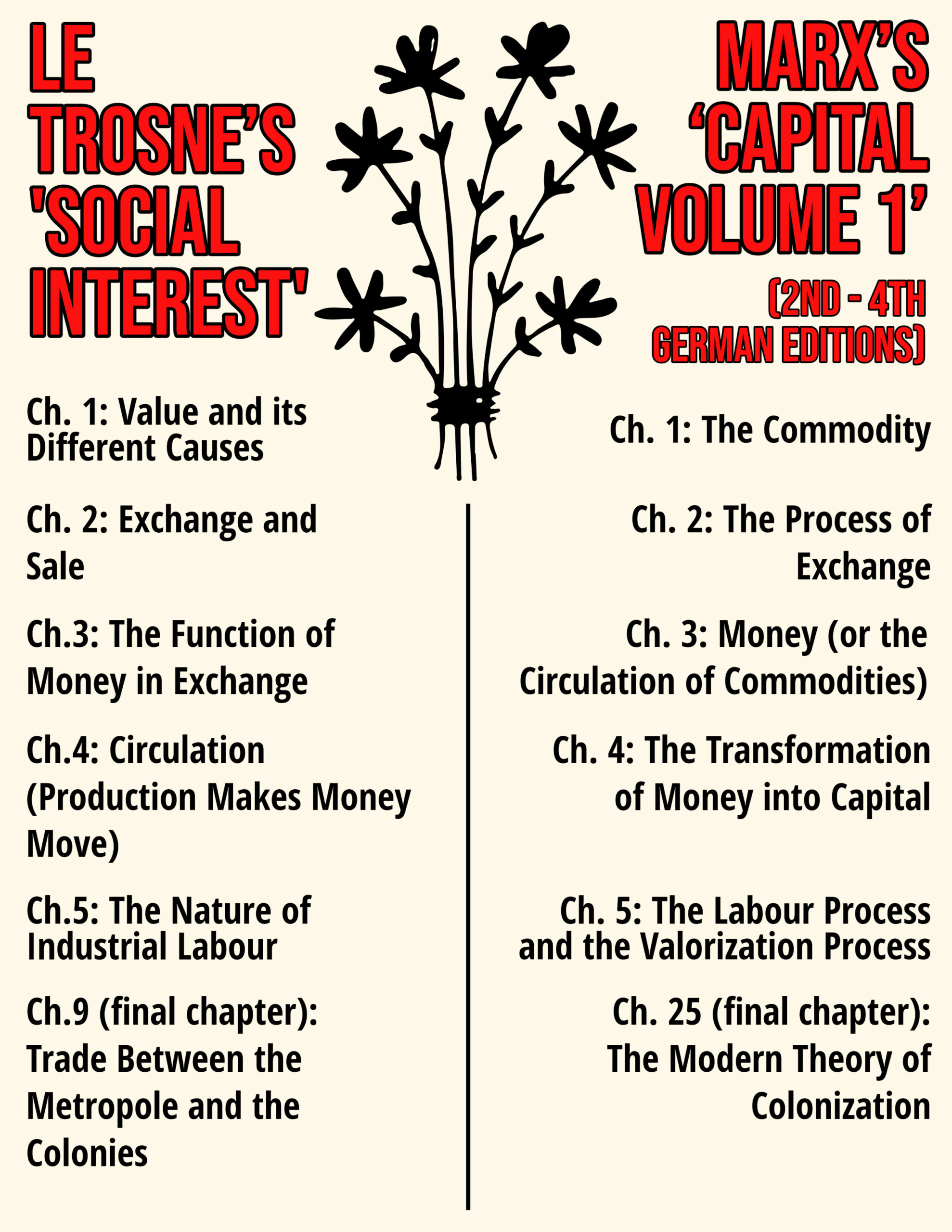

The book structure of Le Trosne’s Social Interest proceeded through a chapter order consisting of: 1) Value and its Different Causes; 2) Exchange and Sale; 3) The Function of Money in Exchange; 4) Circulation, Production Makes Money Move; 5) The Nature of Industrial Labour; 6) On the Nature and Effects of Commerce; 7) External Commerce; 8) The Effects of Indefinite Freedom for the Nation […]; and 9) Trade Between the Metropole and the Colonies.

Marx put together his order of presentation in Capital Volume 1 in a very similar way. His chapters and parts (in the second to fourth German editions) were ordered as: 1) The Commodity; 2) The Process of Exchange; 3) Money or the Circulation of Commodities; 4) The Transformation of Money into Capital; multiple chapters and parts on Production and Accumulation; and a final chapter, 25) The Modern Theory of Colonization.

In the first German edition, Marx’s order of presentation was exactly the same, only some chapters appeared instead as sub-chapters. In subsequent French and English editions, the order of presentation again remained the same, but some sub-chapters were given their own chapters.

Marx’s structure of presentation and chapter order in Capital Volume 1 more closely resembles that of Le Trosne’s Social Interest than any other work of political economy or philosophy that I am aware of. As far as I know, this strong similarity has also gone completely without comment by scholars of Marx.

Value and its Determinants

Le Trosne’s first chapter of The Social Interest, “On Value and its Different Causes”, begins with a sub-chapter on “Needs and How to Fulfill Them”. The land is the answer, since it’s the ultimate source of all goods.

The following sub-chapter brings human labour into the picture, the intelligence and power of “men” and how it’s applied to the land that labour itself does not originally create.

The third sub-chapter deals with “Consideration of Products as to their Utility and their Value”.

It’s not enough, according to Le Trosne, “to estimate products by their useful qualities.” We must also consider products with respect to their reciprocal exchange, something that derives from their utility.

“The Definition of Value” then forms Le Trosne’s fourth sub-chapter. “In a social state,” Le Trosne argued, “products acquire a new quality that is born from the communication of men with each other: this quality is value, and it makes products become wealth, and there is no longer anything superfluous, since it becomes the means of obtaining what is lacked.”

Le Trosne then presents five determinants of value, each with their own sub-chapter. These being use-value, necessary costs, rarity or abundance, competition, and commodities themselves.

All factors that were important for Marx too, and that were addressed by him, even if he didn’t exactly consider them determinants of value. Instead, Marx put forward three determinants of value in the first chapter of Capital. These being abstract-labour (as quality), labour-time (as quantity), and the social division of labour.

Marx also ended his first chapter (of the second German and first French and English editions), “The Commodity”, with a sub-chapter on the “Fetish Character of the Commodity”, which Marx said arises from the commodity form itself, rather than from the determinants of value. Marx’s choice might not have been coincidence, given that Le Trosne’s last determinant of value was commodities themselves.

In claiming that commodities themselves are a determinant of their own value, Le Trosne meant that “they all enter the balance of trade, and are counterbalanced by each other.”

This related to Le Trosne’s view that only things exchanged or destined for exchange have value, that consumption doesn’t contribute to value, but consumption also first requires exchange, and everyone must put something in the balance for what they receive.

This final determinant also dealt with how the previous determinants, such as rarity or abundance and competition, all interacted with each other through exchange and consumption.

Value as a Social Relation

Although Le Trosne included use-value as a determinant of value, he specified that it was not the measurement of the magnitude of value, that instead “It is competition that regulates the value of marketable goods.”

In a sentence defining the character of value, but not quoted by Marx in Capital, Le Trosne wrote, “It is certain that value is not an absolute, inherent quality of things, even though one can say that value derives from the property of being exchangeable, and that this property belongs to things, since it is the consequence of their useful qualities; but if it [value] is not properly an absolute quality, it is even less an absolutely arbitrary quality, which only exists by virtue of personal judgement of the contractants.”

Le Trosne further explained that “The estimate which we make of a thing can make us decide to buy or not; but the thing does not lose any of its value due to this, because we are not the only buyers and because if it does not suit us, it can suit someone else.”

Clearly, Le Trosne had a social relation theory of value, rather than a so-called embodied or substantialist labour theory of value. He even wrote that “value is nothing other than the exchange relation.”

Value, for both Le Trosne and Marx, was social rather than physical. Social in the sense of society, not merely a single exchange contract between two commodity owners, which for Marx and Le Trosne was itself derived from the wider economic and social relations of production and the market.

However, the Physiocrats as an economic school (unlike Marx, Benjamin Franklin, Smith or Ricardo), thought that only labour in the primary sector (farming, fishing, mining, etc.) was productive of surplus-value, that manufacturing labour instead simply created commodities whose value had already been produced in the primary sector.

Marx, in contrast, argued that it’s not a specific type of labour, but labour’s relation to capital that determines whether it’s productive of surplus-value.

“The secret of the self-valorization of capital resolves itself into the fact that it has at its disposal a definite quantity of the unpaid labour of other people,” wrote Marx. The Physiocrats, he argued, at least understood this aspect of surplus-value, even if they were unable to see through surplus-value’s “mystery”12

Aside from some significant differences, the similarities between Le Trosne and Marx’s thinking and presentation are striking. Yet, practically all anglophone scholars of Marx (or even of politics and economics more generally) are mute on the subject of Le Trosne’s influence, despite the propensity of some to elaborately compare Marx’s work to that of Hegel or Dante Alighieri, or to extensively engage with Marx’s theory of value and the value-form (see the works of Chris Arthur, William Clare Roberts and Michael Heinrich). This is simply an observation of disproportionate attention, not a condemnation. We each choose to research what interests us.13

One exception is TG van den Berg and his 1998 PhD thesis, Dissident Physiocrats, where he writes, “The central notion of Le Trosne’s (and physiocratic) theory is that of reproduction and the circular flow. […] Marx clearly favours Le Trosne’s approach.”

One might hope the general neglect of Le Trosne to be due to his vile and backhanded defence of slavery at the end of his book, but more likely, anglophone (and perhaps other non-francophone) scholars have simply not taken an interest in Marx’s plentiful references to Le Trosne’s work and its indication of some significant influence on Marx’s theory of capitalism.

* * *

Graphic by M.Gouldhawke

* * *

Notes:

- The Labour-Power Theory of Capital, by M.Gouldhawke, 2022

- Karl Marx, Capital Volume 1, Penguin edition, pg.129-130

- Marx, Capital Volume 1, pg.184-185

- Marx, Capital Volume 1, pg.196

- Marx, Capital Volume 1, pg.200, 206-207

- Marx, Capital Volume 1, pg.212

- Marx, Capital Volume 1, pg.215

- Marx, Capital Volume 1, pg.260

- Marx, Capital Volume 1, pg.263, 266

- Marx, Capital Volume 1, pg.318

- See also Friedrich Engels’ suggestion to Marx regarding Hegel’s use of subheadings; https://wikirouge.net/texts/en/Letter_to_Karl_Marx,_June_16,_1867

- Marx, Capital Volume 1, pg.672

- Christopher J. Arthur, The New Dialectic and Marx’s Capital, 2004, The Spectre of Capital: Idea and Reality, 2022; William Clare Roberts, Marx’s Inferno: The Political Theory of Capital, 2017; Michael Heinrich, How to Read Marx’s ‘Capital’, 2021

Also by M.Gouldhawke, on capitalism and Marx

The Labour-Power Theory of Capital