From ‘The Canadian Forum’, November 1981, Toronto [Dish With One Spoon Territory]

For those close to the struggles of the native people of Quebec during the past decade, this summer’s series of violent confrontations between the provincial government and the native population came as no surprise.

More than two years ago Remi Savard, a noted anthropologist and the author of numerous books on Quebec Indians, warned that the province was “heading into the arms of an Amerindian October Crisis.”

Savard, who describes himself as a card-carrying member of the Parti Quebecois, was concerned by what he saw as his government’s short-sighted Indian policy, the main thrust of which was the removal of the native peoples as an obstacle to Quebec independence by luring or forcing the ten tribes in the province into signing agreements with Quebec on as many areas of native life as possible.

Strategists for the PQ hoped that by tying the Amerindians to Quebec with a web of bilateral commitments, they could neutralize the federal government’s Indian card in any future negotiations on Quebec sovereignty. With 80 per cent of their territory under some form of native land claim, the PQ feared that Ottawa’s unchallenged custodianship over the Indians and Inuit could be used to block secession.

As it unfolded, this summer’s Quebec-Indian turbulence could be seen to be intimately connected to Quebec’s controversial policy. Behind the struggle of a few thousand Indians to set their fishing nets as their ancestors had lay five years of mutual hostility and mistrust between the sovereigntist government trying to extend its powers and the native people trying to protect theirs.

The first clash was not long in coming. Within months of the 1976 PQ victory the lines between Quebec City and the indigenous people were being drawn over Bill-101, the language law. While no one can honestly question the justice of the language law in taming the arrogance of English Montreal, Bill-101 was curiously insensitive when applied to the 70 per cent of Quebec Amerindians whose second language, if they have one, is English rather than French. For the partially or wholly assimilated Anglo-Indians, the prospect of forced assimilation into the francophone culture took on a threatening tone. Apart from the high social cost of switching colonialisms in mid-stream, the bill caused native groups like the Cree, the Inuit, and the Mohawks to worry that they would become isolated from the main body of their tribes living in adjacent provinces.

After a minor uprising in the Inuit community of Fort Chimo, the language law was amended slightly as it applied to native people but a statement of intent to make Quebec Amerindians as French as Ontario’s were English was left intact. At the time of a genuine Amerindian cultural revival in Quebec, Bill-101’s Indian clause is viewed by the indigenous population as sort of a Quebecois Lord Durham report.

Land as much as language is central to native culture and to the current Quebec-Indian conflict. And here too the PQ has shown a harmful intransigence. After justly criticizing the Bourrassa regime for bulldozing through the James Bay treaty, the PQ has turned around and taken the hardest possible line on native land claims. In their white paper on sovereignty-association the government stunned the native people by stating that after the 1977 signing of the James Bay agreement into law, there were no longer any legitimate claims on Quebec territory. This despite the fact that Indian groups like the Montagnais, whose traditional tribal lands account for the north-eastern quarter of the province, have never signed a land treaty with any government, federal or provincial.

The PQ’s policy of claiming mastery over native affairs has extended into many other areas as well. Before Restigouche, smaller scale police raids on native fishermen and hunters were already as regular as the seasons. And at a time when Indians were trying to preserve their territorial integrity by launching their own reserve police forces, Quebec Provincial Police (QPF) officers were being encouraged to make regular forays onto the reserves. This dispute came to a tragic climax in 1979 when a young Mohawk, David Cross, was shot dead in front of his own house by a QPF officer because he, Cross, was banging on the squad car with a stick. Mohawk anger over the incident rose to a fury when the PQ Justice Minister Bedard refused to charge the police officer, or even to fire him.

A year after the Cross killing, it was the Cree’s turn. In 1980 Quebec took over the management of the final Cree villages in the area of the James Bay treaty over the strenuous objections of the Cree people. When a serious epidemic of gastro-enteritis broke out in the villages, the province refused Indian pleas for funds to upgrade their health and sanitation facilities, and instead took over the Cree administered health board. In the end, eight Cree children were dead, and no emergency aid was given the remote communities.

By the time Quebec got around to negotiations with the Micmacs of Restigouche this spring over limiting salmon fishing rights, the provincial government was already seen by the province’s indigenous people as their number one enemy. From cautiously supporting the PQ before the election of 1976, the Indians had come to describing the Levesque government in an unending stream of acid epithets. PQ cabinet ministers were scorned as racists, as bandits, and especially as hypocrites, for demanding independence and self-determination for the Quebecois, while denying even limited autonomy to the native peoples within its borders. “The thinkers of the Quebec government should take a look at themselves in the mirrors they intend to trade with the Indians,” was the way one Montagnais chief summed up his people’s frustration in dealing with the province.

It is hardly surprising then that Fish and Game Minister Lucien Lessard’s order to the Micmacs to restrict their salmon fishing to three days a week, 24 hours a day (from the traditional Micmac practice of fishing twelve hours a night, six days a week during the salmon run), was met with a firm refusal. Micmac leaders insisted that native fishing rights were guaranteed under the federally administered Indian act and were beyond the reach of a provincial government. Lessard’s response was to substantially increase the level of Indian-white conflict in the province with the well-publicized police raids of June 11 and June 20.

In both raids more than 250 heavily armed police descended on Restigouche from land, sea, and air, in helicopters, fisheries boats, trucks, buses and more than 40 squad cars. Tear gas was fired into crowds of shocked fishermen. Those who tried to resist the confiscation of their nets from the river, from their moored boats, and from their homes, were badly beaten.

Along with the beating came racial slurs, death threats, and sexual insults aimed at Micmac women. In a signed affidavit one woman reported seeing “a three and a half year old child kicked by a policeman, and another pulling a young man along the ground by his hair.” Others reported police cursing, “the goddamn savages,” and warning. “If we have to kill, we’ll kill. We’ve got our orders.” In the end, the punitive raids cost the Micmacs an estimated $70,000 in nets and equipment. In the long run, however, they may cost the PQ even more dearly.

The response of native people across the province was immediate and emotional. The Restigouche leader Chief Alfonse Metallic vowed his people would continue fishing with borrowed nets, and that lives would be lost if the QPF stepped onto his reserve a third time. The Confederation of Indians of Quebec condemned the raids as an operation of the “Quebec Gestapo,” and accused the government of using tactics taken straight out of Mein Kampf.

But it was not only bitter condemnations the Indians offered in support of their Micmac cousins. Within half an hour of the first reports of the raids, a thousand Mohawks from the Caugnawaga reserve outside of Montreal streamed onto the Mercier bridge on the St. Lawrence river and blocked traffic in protest. Within hours Indian leaders from across the province were pouring into the small village on the Quebec- New Brunswick border in support of the defiant Micmacs.

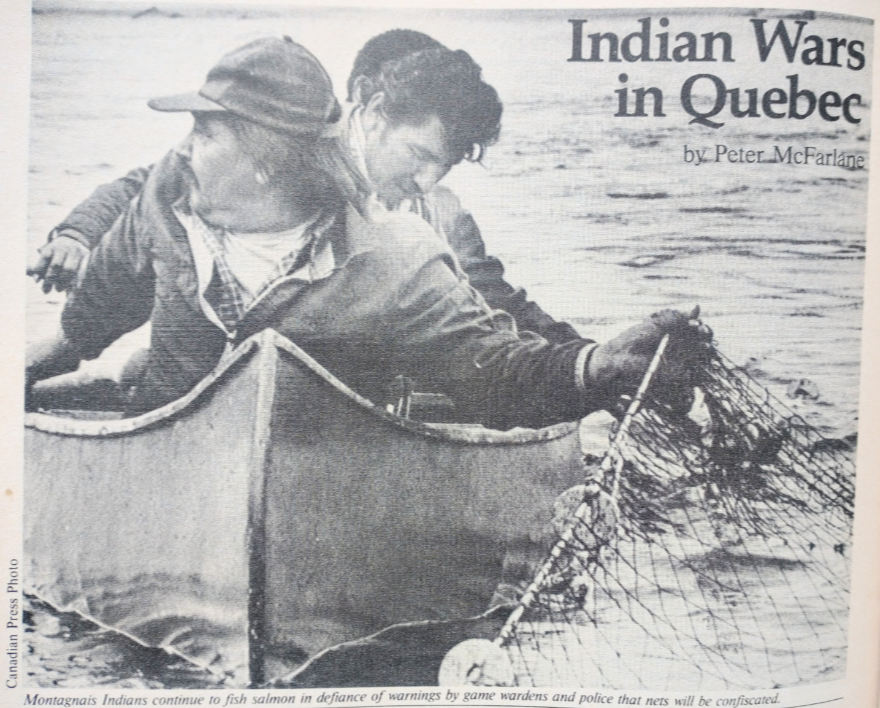

In the interior of Quebec the largely French speaking Attikamek-Montagnais people broke off all talks with the province and began setting salmon nets on the north shore of the St. Lawrence in protest. This prolonged the so-called salmon war throughout the summer, with further police raids on Montagnais fishing activities. In one ugly incident 300 townspeople from Les Escoumins were led by the local Mayor in an attack on a dozen young Indian fishermen.

But the lasting legacy of the Quebec police raids, and the assimilative Indian policy that set the stage for them, came later. On August 4 band leaders from across Quebec met in Duchesnay, a small village 45 miles north of Quebec city, to plot a common front to meet the province head on, not only on salmon fishing rights, but on the whole Quebec Indian policy.

Because of what one band leader described as “unbalanced” press coverage in Quebec, the meeting was closed to journalists. But I later spoke at length with Mohawk councilman Joe Norton, who represented his people at the conference table. Mr. Norton stressed the significance of the fact that the new common front was linked at the band level with representatives of all but one of the province’s 41 native bands attending the meeting. A purely tribal organization, Norton said, was insufficient because it tended to attract representatives of the urban Indian communities in disproportionate numbers. The message rarely reached the isolated bands that still make up two thirds of Quebec’s Amerindian population.

Mr. Norton also insisted that the common front was not intended to be a formal organization with a bureaucratic structure. Instead it is to be based on native traditions, like the Iroquois confederacy of the 1600s formed to combat the original white invasion of Indian lands. Like the Iroquois councils, Quebec Indians will meet three or four times a year to iron out any differences, and to plot a common position on problems of the moment.

If the first meeting is any indication, the front could have far reaching consequences for native affairs in the province. Its first act will be to co-ordinate a series of legal challenges against the provincial government. This will include using the courts to stop or stall all Quebec development projects, and to challenge the province’s right to interfere with native hunting and fishing rights. This last will include a careful program of civil disobedience during the hunting season, with native hunters from across the province moving in to recently forbidden areas.

The escalation of the Quebec-Indian battle is already putting many of the progressive minded pequistes in a quandary. While the centre-right coalition controlling the PQ sometimes acts as if the indigenous people are little more than redskinned federalist agents in the province, progressives like Remi Savard believe the PQ is making a horrific mistake in not recognizing basic autonomous rights for the Indian and Inuit people within Quebec’s territory.

In an interview with the weekly, Perspectives, Savard claimed that independence for Quebec won at the expense of the legitimate demands of the native peoples would saddle the new state with a permanent Palestinian problem. “I have my PQ card, I’ve been contributing to the party for ten years,” he told the reporter. “In declaring that my government is leading us into a sewer, I’m thinking of the future of my country, of my children and my grandchildren. I’d prefer to remain stranded in sovereigntist groups than to build my country on the ruins of peoples we have wronged, and to pass on those wrongs to my children. If we do not begin to run our affairs on the basis of equality with the Amerindians,” Savard concluded, “we will never be able to define ourselves as a people.”

Savard’s views were echoed by a number of other prominent independantistes in the wake of the Restigouche raids. Well known writers like Simone Monet-Chartrand and Pierre Vadeboncoeur, and poet Gaston Miron, were among those who signed petitions condemning the PQ Indian policy. Pro-independence newspapers like Presse Libre asked how the PQ could uphold the right of self-determination of national groups when opposing the Trudeau constitutional powerplay, while it freely used its own state power to suppress any move toward self-determination among small national groups in Quebec?

The effect of these ripples of discontent from within the party are difficult to gauge. The left in the PQ has had very little influence on policy matters since the party formed the government in 1976. It does seem unlikely that the present conservative-minded cabinet in Quebec City will suddenly raise the issue of native rights to the position of a key building block for the New Quebec. But until it does, sovereigntist Quebecois will have to deal with the strong Indian emotions found behind the graffiti “Iroquois pas Quebecois?” on the walls of buildings on the Caugnawaga reserve.

And, with the formation of a Quebec Amerindian common front, Premier Levesque may find that the confederation he now describes as two scorpions in a bottle will have been joined by a third.

Also

The Indian Claims Commission is illegal, unjust and criminal, by Karoniaktajeh (1965)

Palestinians and Native People are Brothers, by the Native Study Group (1976)

No Surrender – Howard Adams on the Oka Crisis (1990)

How to Become an Activist in One Easy Lesson, by Joe Tehawehron David (1991)

Thoughts on the Constitution and Aboriginal Self-Government, by Howard Adams (1992)

Indigenous Intifada: Federal MP Compares Natives to Palestinians (2002)

Mohawks Kick Cops Off Rez, by M.Gouldhawke (2004)

Indigenous Resistance, 1960s to 2007, by Warrior Publications (2007)

Audio interview with Wade Crawford from Six Nations of the Grand River (2010)

IdleNoMore in Historical Context, by Glen Coulthard (2012)

Oka Crisis, 1990, by Warrior Publications (2014?)

Another Word for Settle: A Response to Rattachements and Inhabit (2021)

Remembering Jeff Barnaby (2022)