From ‘KPFA Folio’, September 1976, Berkeley, California

“Bob and I have never killed anybody in our lives. It is against our spiritual and moral beliefs to take another human being’s life. We believe we have the right to protect the lives of our people when their lives are threatened by violence that is unwarranted.

“We are members of a sovereign nation. We live under our own laws, tribal and natural. We recognize and respect our traditional and elected leaders. The treaties that were made between Indian nations and the U.S. government state we have a right to live according to our laws on the land given to us in the treaties; that the laws of the U.S. government shall not interfere with the laws of our nations.

“This trial concerns all people and their rights. Each day we learn more of government, FBI and CIA misconduct. We must all work together to remind the United States that their government is ‘for the people.’ ”

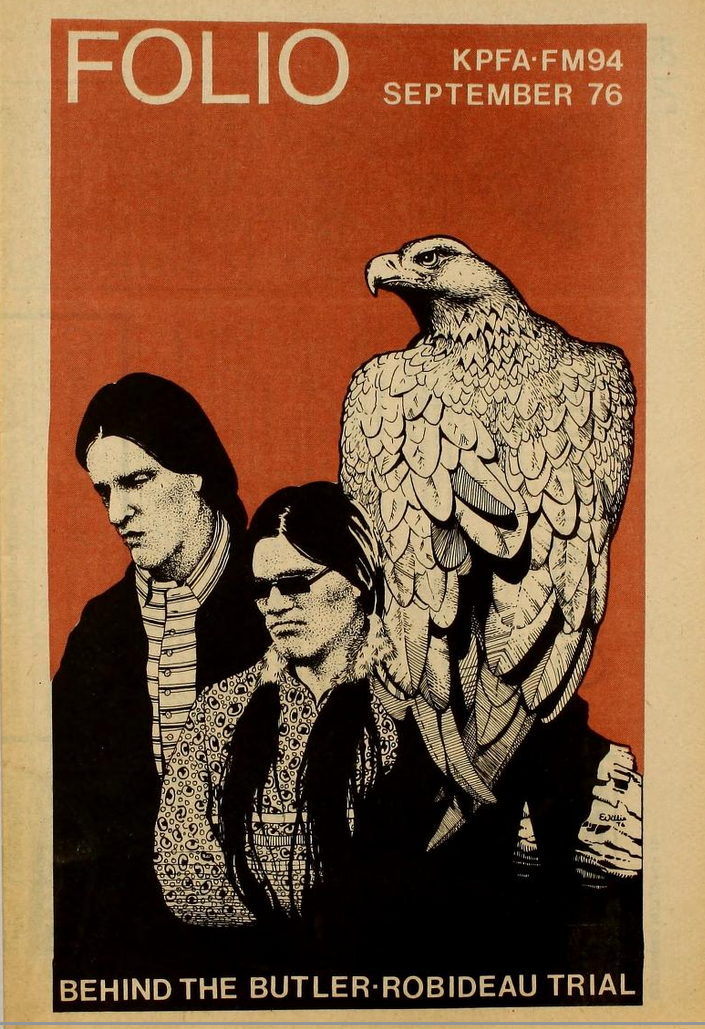

In June, 1976, Darrell “Dino” Butler read this opening statement to the jury that would determine the fate of himself and his co-defendant Robert Eugene Robideau. These two American Indians were accused of ‘aiding and abetting’ the murder of FBI agents Jack R. Coler and Ronald Williams. The charge stems from the ‘shoot-out’ which occurred June 26, 1975, outside the tiny village of Oglala on the Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota. That charge carried the same weight as a first-degree murder charge and could have resulted in life imprisonment.

From the beginning, the public has been offered only one explanation of the deaths of the agents. The FBI and the government of South Dakota have tried to stampede the public into thinking that the agents were victims of an ‘ambush’ attack by a bunch of renegade Indians who mercilessly ‘took turns’ shooting each agent. In the beginning AP [Associated Press] and UPI [United Press International] carried stories of ‘sophisticated bunkers’ which later turned out to be horse shelters. All of this erroneous information came from the FBI.

According to the FBI, the two agents had spent several days looking for Jimmy Eagle, the 18-year-old grandson of Wounded Knee activist Gladys Bissonette. Eagle was being sought on an alleged burglary charge. On June 25th, Agents Coler and Williams detained three youths who were living in the Jumping Bull area. One of the youths was Norman Draper, an 18-year-old Navajo from Many Farms, Arizona.

Draper, also known as ‘Wish,’ said the three were taken to the local BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs) police for identification since the agents didn’t know what Eagle looked like. The three were then released. The following morning, June 26, Wish was hauling water in the tent area when the gunfire began. He hid in a nearby ravine until the gunfire ended and then he rejoined the others in the tent area. He later fled to Canada but returned to his home in Arizona where he was taken into custody by FBI agent Charles Stapleton. Wish said he was thrown up against a truck and later tied to a chair. He was told he would be charged with the murder of the agents if he didn’t cooperate.

During this time, he was not allowed to see a lawyer and so he relented and talked. Wish explained that agent Stapleton and others had offered him “a new life, new identity, education in preparation for a job and protection, if necessary.” Wish was the only Indian witness to take the oath on the Bible and not on the Sacred Pipe.

There is no way of knowing if Wish’s life has improved but we do know that coercion is a common practice for the FBI. Senator Frank Church, who headed the Senate committee that investigated FBI activities, submitted a report published in April titled: Intelligence Activities and the Rights of Americans, Government Printing Office, Report No. 94-755, that documented these FBI tactics.

Norman Brown, a 16-year-old from Many Farms, Arizona, was the first of many Indian witnesses to take his oath on the Sacred Pipe and also the first to testify about the climate of tension and fear on the reservation. He rose late on the 26th because he had been on ‘security’ the night before. ‘Security’ is a common practice among AIM (American Indian Movement) people and their supporters because of fear of attack. Rifles are common on the Pine Ridge Reservation; 350 unsolved murders in three years have taught the people to be cautious and wary of strangers. Brown testified that he and Joe Stuntz were sitting on a car and talking when they heard the gunfire begin. They ran uphill to the nearby houses to find out what was happening. Fearing the camp was under siege, they ran back to the camp and picked up rifles.

Brown told the jury that the eight males in the camp “were prepared to die, if necessary,” to protect the women and children. Brown’s companion, Joe Stuntz, died defending the camp area but no one has been charged with his murder.

Brown said the group feared they would all die but decided to attempt to leave. Before they left they gathered in the woods and prayed for several minutes. An eagle came and landed in a tree. The group was now the object of a massive manhunt involving over 275 law officers, two armored personnel carriers, along with helicopters and airplanes. They stopped many times to pray and each time the eagle came to them. Finally as the sun was setting the eagle flew into the sunset. “We knew it would be alright, we would be safe,” said Brown. There was no talk of ambush and the group did not learn of the agents’ death until after their departure from the area.

According to former BIA policeman Marvin Stoldt, agents Coler and Williams were “very arrogant and abusive.” Jack R. Coler had just been transferred to the reservation from Denver, Colorado; he was a special agent, a member of the Special Weapons and Tactical Squad, commonly known as SWAT. Ronald Williams was a member of the Rapid City branch of the FBI formed as a result of the Wounded Knee Occupation of 1973.

Throughout the six-week trial, held in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, the government wanted this case presented as a simple murder case and limited evidence to the events of June 26. By doing this they successfully avoided the issues that Indian people feel should be on trial. Although the acquittal was a personal victory for the defendants, the unresolved issues of sovereignty, treaty rights and other unsolved murders remain.

The execution style murder of Anna Mae Aquash in February of 1976 and the subsequent FBI cover-up opens up another chilling and bizarre chapter of FBI involvement on the reservation. The government would not allow any evidence about FBI involvement concerning Anna Mae to be heard during the Butler-Robideau trial. Before her death, she had been planning to testify for Butler and Robideau.

Anna Mae was a true ‘warrior’ working for her people both here and in Canada. She was a MicMac Indian from the Shubenacadie Reserve in Nova Scotia. She had been active in the movement since the Trail of Broken Treaties in Washington and always worked for a better life for her people whether she was in St. Paul, Wounded Knee, Los Angeles, or Oregon. Anna Mae had adamantly refused to cooperate with the FBI and was painfully aware that her life was in danger.

Last winter Anna Mae telephoned her sister in Nova Scotia and said that her life was in danger because of her involvement in the movement. She told her friend John Trudell, national chairman of AIM, to “remember her whenever it rained,” a painful memory for Trudell because he says he didn’t understand her warning in time.

On February 24, 1976, her body was found in a field near the village of Wanblee. The BIA coroner who examined the body declared death by exposure. Her body was unidentified at the time, and buried in an unmarked grave. Oddly enough the last person to see her alive and the first official to view the body was Agent David Price. Price should have been able to identify her because it was common knowledge that Price was fanatically seeking her on a warrant. Furthermore, Price had already threatened her with only one year left to live.

The terrifying and bizarre aspect of this case centers around the insistence that the body was unidentifiable, which resulted in her hands being severed from her body and sent to Washington for identification. The question of exposure was resolved in a second autopsy that showed a bullet in the back of her head. FBI efforts to hide her identification also included the severing of her fingertips from her fingers and even the slashing of her fingertips.

The traditional leaders of Oglala issued this statement concerning her death: “Anna Mae Aquash was respected and loved by the people of Oglala. We mourn her and we urge all law-abiding citizens to demand the real truth behind her death.”

FBI involvement on the Pine Ridge Reservation reached its peak during the investigation of these two incidents. The U.S. government has already spent 50 million dollars on the investigation of the agents’ death. Government intervention into Indian affairs is not a new tactic. Throughout the last 200 years Indian people have been involved in strong and consistent resistance to a nation founded illegally in their midst. It is because of this resistance that agencies such as the FBI are waging ‘war’ on reservations. The “Indian wars” are perpetuated by the silent consent of a nation of non-Indian patriots and land thieves, Christians and non-Christians, greed and lust hand-in-hand with the word of God, the divine rights of the Constitution, and the Declaration of Independence.

Sovereignty, treaty rights, and unsolved murders are the issues for Indian people. What is the FBI doing to American Indians at Pine Ridge and to other U.S. citizens? The jury acquitted Bo and Dino but will Indian people acquit the FBI? Think about it the next time it rains. . .

Peggy Berryhill

(At the time of this writing Butler and Robideau are still in prison. Throughout September, Native American Culture will bring you tapes recorded in Cedar Rapids.)

Also

The Six Nation Iroquois Confederacy stands in support of our brothers at Wounded Knee (1973)

Wounded Knee: The Longest War 1890-1973, from Black Flag (1974)

“Jails are not a solution to problems” – Anna Mae Pictou Aquash interviewed by Candy Hamilton (1975)

Indian Activist Killed: Body Found on Pine Ridge, by Candy Hamilton (1976)

Anna Mae Lived and Died For All of Us, by the Boston Indian Council (1976)

The Brave-Hearted Women: The Struggle at Wounded Knee, by Shirley Hill Witt (1976)

Repression on Pine Ridge, by the Amherst Native American Solidarity Committee (1976)

400 Years Later, by Leonard Peltier (1976)

Chronology of Oppression at Pine Ridge, from Victims of Progress (1977)

Excerpts from Leonard Peltier’s Trial Statements with Regard to Anna Mae Pictou Aquash (1977)

The Life and Death of Anna Mae Aquash, by Johanna Brand (1978)

Review of ‘The Life and Death of Anna Mae Aquash’, by Akwesasne Notes (1978)

Anna Mae Aquash, Indian Warrior, by Susan Van Gelder (1979)

Indian Activist’s Bold Life on Film, by John Tuvo (1980)

Poem for Nana, by June Jordan (1980)

In the Spirit of Crazy Horse, by Peter Matthiessen (1983)

The Trial of Leonard Peltier, by Jim Messerschmidt (1983)

Against the Corporate State, by Gary Butler (1983)

Lakota Woman, by Mary Brave Bird and Richard Erdoes (1990)

Pine Ridge warrior treated as ‘just another dead Indian’, by Richard Wagamese (1990)

Solidarity from Anti-Authoritarians, by Leonard Peltier (1991)

Leonard Peltier Regarding the Anna Mae Pictou Aquash Investigation (1999-2007)

A Report on the Case of Anna Mae Pictou Aquash, by Zig-Zag (2004)

Feds to re-examine Pine Ridge cases, by Kristi Eaton (2012)

Anna Mae Pictou Aquash: Warrior and Community Organizer, by M.Gouldhawke (2022)