(Imposed PDF of this article for printing and Spanish translation via Libértame)

by K. C. Sinclair

May 9, 2025

(minor correction and notes added September 10)

What is “revolutionary defeatism,” where does it come from, and what is its current relevance for anarchists and other social rebels? As a slogan and stance, revolutionary defeatism was devised by the Russian statist socialist Vladimir Lenin and, to a lesser extent, the Ukrainian statist socialist Grigory Zinoviev, in the context of the First World War.

Given this origin, before we even know what revolutionary defeatism is, its relevance to anarchists is called into question, not only because anarchists are typically defined by their opposition to statist means and ends, but also because more than a century has passed since this particular political position was developed.

However, colonialism and war, the building blocks used to construct the theory of revolutionary defeatism, are very much still with us. The current wars of occupation in the Middle East and Eastern Europe, in addition to the recent anti-colonial uprising in Kanaky (New Caledonia), make revolutionary defeatism more topical than ever. The ongoing colonial conflagration in the Middle East is also partly a result of WWI and the subsequent awarding of mandates (colonies) to the United Kingdom and France by the League of Nations. The France that some anarchists and statist socialists thought needed defending from the invading Germans in the Great War has itself yet to end its own invasions and occupations of Kanaky and other territories more than a century later.

Furthermore, anarchists, by the time WWI broke out, had already been developing their own anti-colonial and anti-militarist analysis independently from the statist socialists for decades. Certain elements of this earlier anarchist theory would even be echoed by Lenin and Zinoviev once they began to define their revolutionary defeatism. These statist socialists did not, however, appear to be aware of this or willing to acknowledge it. They even made the false claim in their autumn of 1915 text, ‘Socialism and War’, that the most prominent anarchists of the time period were supporting the war, that anarchists were opposed to civil war by the oppressed class against the oppressing class, and that anarchists did not deem it necessary to study each war in its particularities.

In reality, most prominent anarchists of the era immediately denounced both WWI and the few high-profile anarchists, such as Peter Kropotkin, who supported it. Most anarchists, in fact, did support civil war of the oppressed against the oppressors. They hadn’t just analyzed militarism in general but also the concrete conditions of particular wars, for example, the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, the Spanish–American War of 1898, the Second Boer War of 1899-1902, the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, the Second Melillan Campaign of Spain against Morocco in 1909, and the Mexican-American Border War of 1910-1919.

In some cases, the anarchists’ ideas were based, in part, on first-hand experience, unlike the statist socialists Karl Marx and his follower Vladimir Lenin, academic philosopher jurists who observed and contemplated wars and uprisings from the arm chair, at a safe distance.

Statist Socialists Define Their Defeatism

In 1914, just before the Great War for colonies broke out, Lenin asked, “Can a nation be free if it oppresses other nations?” He answered that it cannot.

In this, he was echoing, consciously or not, the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin’s claim from 1871 that “I am not myself free or human until or unless I recognize the freedom and humanity of all my fellowmen,” as well as Bakunin’s 1873 proclamation that “every nation, like every individual, is of necessity what it is, and has an unquestionable right to be itself.”

For Lenin, the premise of his revolutionary defeatism was the division of the world into colonizing and colonized countries, with the First World War being a squabble among the imperialists over the looting of the colonies.

Revolutionary defeatism was a slogan and stance for the revolutionaries of the colonizer countries, in part a prescription for them to oppose the imperialism and nationalist chauvinism of their own states, “the great powers”, with special attention to the concrete conditions of inter-imperialist war.

It was in no way a prescription for the colonized peoples to not resist their colonization, Lenin and Zinoviev making this as explicit as they possibly could in ‘Socialism and War’, where they stated that “if tomorrow, Morocco were to declare war on France, India on England, Persia or China on Russia, and so forth, those would be ‘just,’ ‘defensive’ wars, irrespective of who attacked first; and every Socialist would sympathise with the victory of the oppressed, dependent, unequal states against the oppressing, slave-owning, predatory ‘great’ powers.”

From this we see that revolutionary defeatism was not some ultra-abstract “no war but class war” stance in which wars of national liberation were deemed as equivalent to imperialist wars of occupation, or all sides were to be opposed equally. We can note also that Lenin defined his revolutionary defeatism not just in opposition to the statist socialist turncoats who were now supporting imperialist war but also in contrast to the anti-war yet reductive stance taken by statist socialists like Leon Trotsky, who disagreed that the military defeat of an imperialist country like Russia would be the “lesser evil” from the perspectives of the revolutionaries within that country.

We can also extrapolate from Lenin’s revolutionary defeatist policy up to the present era and see that there can be no revolutionary defeatism for Palestinians as long as Israel invades and occupies their lands, nor, for that matter, for Ukrainians with regard to Russia’s invasion and attacks. At the same time, there can and should be a revolutionary defeatist stance taken up by revolutionaries within Israel and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) countries against their own governments, regardless of the fact that their governments may also support, in the sense of using as cannon fodder, Ukraine or Rojava, etc.

There can be no hall pass for imperialism when it purports to support a just struggle, particularly when some Western arms companies have supplied Israel and Ukraine at the same time, the Ukrainian state has purchased Israeli weapons, and the United States used its ammunition cache in Israel to supply Ukraine.

For Lenin, in the context of WWI, revolutionary defeatism was also not solely about opposing one’s own ruling class. If we think about it, we can presume that revolutionaries oppose their own ruling class always, in times of peace as in times of war. Simply continuing the struggle in times of war did not necessitate any new theory or slogan such as revolutionary defeatism, just as maintaining the fight when it’s rainy outside did not require any new policy such as ‘revolutionary dampness’. The term ‘revolutionary’ was enough to cover all such circumstances.

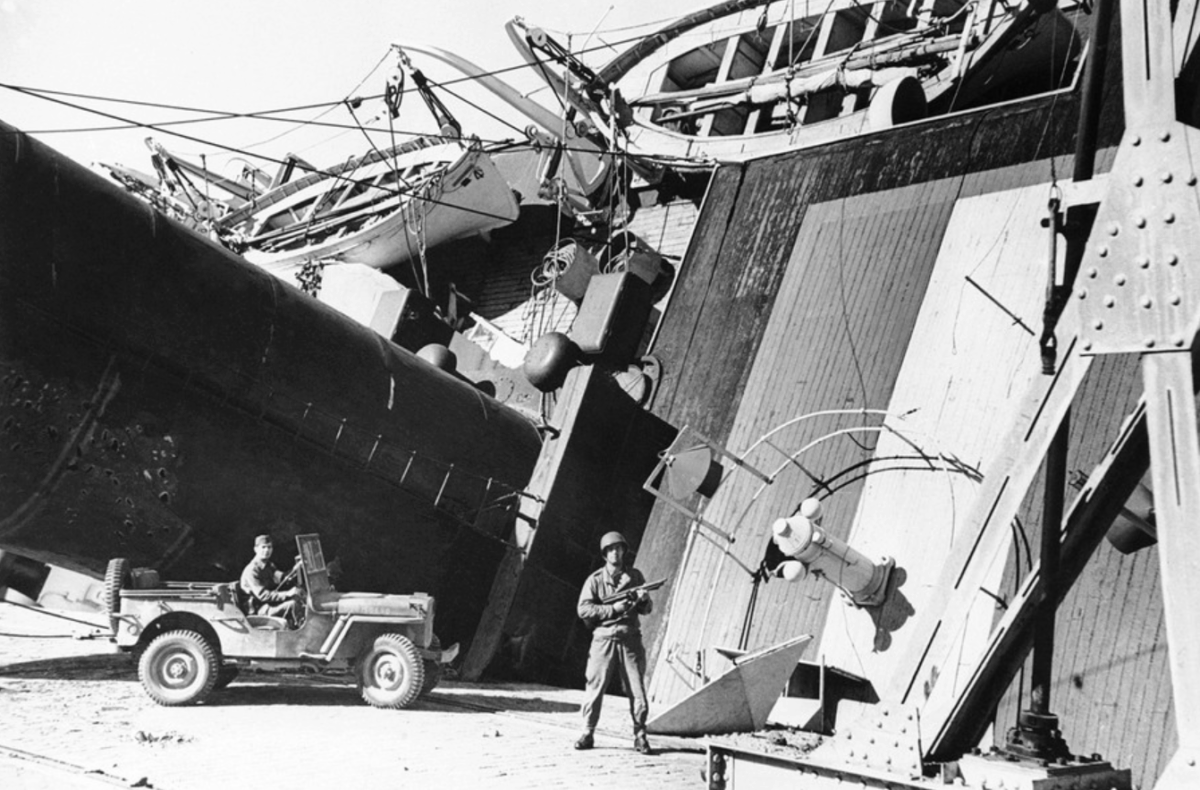

From this it follows that ‘defeatism’, in the revolutionary sense, was not strictly about the proletariat of each country defeating its own bourgeoisie. ‘Revolutionary’ covered that well enough too. The ‘defeatism’ in question referred specifically to military defeats suffered by colonizer states at the hands of their fellow states, not defeats suffered at the hands of the revolutionary workers. Yet, this also didn’t mean that the proles had no role to play under such conditions. The multiple military defeats suffered by Russia at the hands of Japan had contributed to the revolutionary uprising of 1905 in Russia, including among the Russian armed forces, most famously by the sailors of the Battleship Potemkin.

There was still a relationship between revolutionary struggle and military defeats, to be sure, even if they were not identical to each other. One couldn’t really struggle against one’s own imperialist government in times of war without weakening it, including in the military-strategic sense. On the other hand, one could take advantage of the opportunities that military defeats presented to proles within each imperialist country.

As it turned out, Lenin and the anti-war anarchists were right about at least a couple of things, while Kropotkin and crew were very wrong. The defeats suffered by Russia and Germany in WWI did lead to social revolution, with mutinies among the armed forces, like in Russia in 1905. The victory of the Allies did not end militarism and colonialism, it only worsened them, contributing to the calamities we still face today. Absurdly, some anarchists still refuse to learn the lessons of Kropotkin’s unforced errors, touting more NATO weaponry and carnage on the battlefield as the true solution to imperialism in the face of Russia’s assault on Ukraine, as if Western imperialism and militarism were the lesser evil from the perspective of their victims, as if one could fight them with imperialist and militarist means.

Anarchists Against Militarism and Imperialism

In the months leading up to the outbreak of WWI, Emma Goldman’s already anti-militarist Mother Earth print journal had put itself on even firmer footing regarding the matter because the United States had just invaded Veracruz, Mexico, in April of 1914.

“There are a hundred reasons why American workingmen and all men and women of liberal thought should oppose the war that the government of the United States has started against Mexico,” declared Leonard D. Abbott in Mother Earth’s pages.

In August of 1914, the majority of the prominent anarchists of the time period, from Luigi Galleani to Ricardo Flores Magón to Emma Goldman, immediately denounced WWI in their print journals. In most cases (although not Magón’s) they also directly criticized the few high-profile anarchists such as Kropotkin who had broken with anarchism by siding with the French state and its Allies. Prominent anarchists such as Alexander Berkman, Errico Malatesta, and Vicente Garcia wrote open letters or articles in various anarchist print journals excoriating the pro-French and pro-Belgian position of Kropotkin and his flunkeys. Garcia, in the pages of Tierra y Libertad in November of 1914, even went so far as to say that he would vote for the expulsion of Kropotkin and his fellow warmongers from the International Anarchist Congress if the war hadn’t interfered with the holding of the event.

The ‘International Anarchist Manifesto on the War’ appeared in the print journals Freedom and Tierra y Libertad in March of 1915, then in Mother Earth in May of 1915. In the text, 36 signatories from Europe and the United States declared that war, including its colonial variant, was “the natural consequence and the inevitable and fatal outcome of a society that is founded on the exploitation of the workers.”

Militarism could not defeat militarism. The State arose from, and was developed and maintained by military force. “It is not by constantly improving the weapons of war and by concentrating the mind and the will of all upon the better organization of the military machine that people work for peace,” the signatories proclaimed.

All the belligerent states were guilty of militarism and repression. France was guilty of colonialism and conscription in Africa and Asia. England exploited, divided and oppressed the populations of its “immense colonial empire.” Therefore, none could make a legitimate claim to self-defence.

The peoples of the belligerent states had mistakenly put their faith in democracy, including parliamentary socialism, to maintain peace. Anarchists should cultivate and take advantage of the “spirit of revolt” and discontent in “peoples and armies.” The only solution was the “free organization of producers” and the “abolition of the State and its organs of destruction.”

The anarchist manifesto was released the same month that the Sotsial-Demokrat published the resolutions from the February to March conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party held in Berne, Switzerland. This issue of Sotsial-Demokrat appears to have been the first public declaration of Lenin’s revolutionary defeatism. Again we note that, at this point, principled anarchists had been speaking out against the war and Kropotkin’s stance on it for months already.

Lenin’s ‘The Defeat of One’s Own Government in the Imperialist War’ was subsequently published in Sotsial-Demokrat in July of 1915, Lenin and Zinoviev’s ‘Socialism and War’ pamphlet was published in autumn, and the Zimmerwald Manifesto wasn’t published until September, by which time the International Anarchist Manifesto on the War had been out for months.

Decades earlier, in the context of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, Bakunin had already explicitly called for civil war as the solution to the Prussian invasion, for revolution against both the French state and the invading Prussians. Rather than wage war through the means of the French state machinery, the people, both peasants and workers, should act autonomously against both the French and Prussian states. Lenin, in his texts on revolutionary defeatism, echoed this earlier call by Bakunin for turning imperialist war into civil war, albeit without acknowledging his fellow countryman and ideological competitor, even claiming the opposite of the truth, that all anarchists were against such a stance.

At the beginning of WWI, the Spanish anarchists of Tierra y Libertad placed the views of Bakunin and Kropotkin side by side, to highlight the stark contrast between them. Both of these anarchist luminaries, at different times, wanted to save France from Germany, but Bakunin wanted it done through class war, whereas Kropotkin wanted it done by way of imperialist war.

Toward Anarchist Revolutionary Defeatism

Bakunin had provided the “civil war” component of a potential anarchist revolutionary defeatism. In the same text, he’d written that if the people “hate conscription,” then it was only right that we “don’t force them to join the army!!” The notorious French anarchist Louise Michel would echo this anti-militarist sentiment in her 1881 article, ‘The Conscripts Strike’. Both had actually taken part in uprisings in France, unlike Marx and Lenin.

But it would be left to the next generation of anarchists to further develop the anarchist critique of militarism, imperialism and colonialism. Militarism was what perpetually led to war, in times of peace as much as in moments of conflict. Most anarchists of this era supported national liberation struggles and opposed imperialism as much as they opposed militarism, but concrete conditions also called for concrete analysis.

In the case of the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, Malatesta and Kropotkin were as of yet united in their stance. The Greeks on the island of Crete were right to seek liberation from the Ottoman Empire. This didn’t mean that their struggle would be that of angels, or the resulting conditions under the Greek king would be ideal, but the object of their struggle, independence, was just.

Yet, there were still other factors to consider, the intervention of other empires such as the British, and the impracticalities of anarchist intervention in this specific instance, given the anarchist principle of the unity of means and ends. Two or more things could be true at once for Malatesta and Kropotkin, the Greeks could be correct to struggle against the Ottoman Empire, and it could also be incorrect for anarchists in other countries to minimize or ignore the intervention of the British or the contradictory nature of anarchists enlisting under statist national forces.

We can extrapolate from this to our current conditions and see that the degree to which it is right for Ukrainians to resist Russian invasion has no bearing on the wrongness of NATO and Israeli militarism and imperialism, particularly given the monumentally brutal treatment of Palestinians and Kanaks by NATO countries. If self-determination is a principle, it goes for all peoples, it is not the private property of Ukrainians, like the uranium they purchase from a Canadian settler corporation operating on stolen Native lands.

Enlisting in a state army and doing propaganda for a statist war effort, particularly a state engaged in conscription, is not consistent with the anarchist principle of the unity of means and ends, no matter how many anarchist patches one slaps on their uniform or how many anarchist flags one flies. If one deems enlisting (rather than the popular and legitimate option of fleeing) as the absolute necessity of the moment, as a matter of life or death, this still does not in any way make such a decision ‘anarchist’, and even less so in the case of any propaganda made for the war effort that portrays anarchist obedience to the military hierarchy as a part of anarchism.

If ever there is a bleak necessity to join the army, there’s never a necessity to paint statism as anarchism. One can simply be honest and admit that they’ve broken with anarchism because statism is presently the only solution, in one’s view. We always need to drink water in order to survive too, but drinking water does not become any more ‘anarchist’ the more parched one becomes, and to publicly portray drinking water as ‘anarchist’ would be to engage in sophistry, all the worse in the case of militarism, something that, unlike water, harms all life on earth. Neither should it be tolerated for anarchists to lie about anarchism and militarism to other anarchists or the general public in order to generate donations or clout when anarchists are engaging in statist ventures.

It’s also not simply a matter of adhering to principle as some abstract ideal detached from everyday experience. Principles are practical, as precisely WWI still shows today. The victory of the Allies over Germany did nothing to end militarism and imperialism, on the contrary, it only increased them, leading to the birth of fascism and the particularly visceral genocides of WWII and today’s Palestine, along with the ongoing French occupation of Kanaky.

War cannot be ended on the military terrain alone because war is also politics and economics. War is social not just technical. Revolution, or for that matter, simple survival or the maintenance of democratic rights, is not reducible to questions of superior firepower or good behaviour as a subservient soldier in a state army. Luckily the world has always held wider options than the crude binary of either apathetically sitting on one’s hands or enthusiastically shouting “sir, yes sir” to one’s commanding officer.

More Militarism More Problems

Looking back in time, the infamous American anarchist Emma Goldman, when referring to the Spanish–American War of 1898, was clear as could be. She had supported Filipino and Cuban independence, but did not have any reason to believe that the Americans were really supporting such independence. How right she was! How stark a contrast to some of today’s American anarchists who foolishly see their country’s army and weapons industry as forces for good in Syria and Ukraine, and fail to see that increasing American militarism can backfire on them back at home.

In the context of the Second Boer War of 1899-1902, things got even messier. Goldman and Malatesta supported the Boers in South Africa against the British, somehow missing the fact that the Boers were colonizers too, much as Goldman failed to significantly address ongoing American colonialism within the continental states.

Nonetheless, Malatesta, who was living in England at this time, was at least clear about one aspect of this inter-colonial conflict. “It is not the victory but the defeat of England that will be of use to the English people, that will prepare them for socialism,” he proclaimed in an article in 1901.

“They say, ‘woe to the defeated’; but for a people that goes to oppress another, for anyone who performs work of violence and injustice, it is truer to say, ‘woe to the victors,’” he continued, “an English victory would be the victory of militarism and would prepare the ground for the suppression of English freedoms.”

Furthermore, “English proletarians live on the products of export and therefore benefit from the subjugation of other people,” Malatesta reminded his readers. A British victory “would reinforce that idiotic national pride, which makes the most miserable English person believe he has the right to dominate the world, and which is such a big obstacle to the advance of emancipatory ideas.”

Here we see not only the idea of the ‘colonial boomerang’ almost half a century before the Martinican socialist Aimé Césaire would revitalize and popularize it, but also new aspects of a potential revolutionary defeatist stance, a decade and a half before Lenin would promulgate it for the Great War.

Bakunin had introduced the concept of turning imperialist war into civil war and now Malatesta had added the idea that military defeats suffered by a colonialist government abroad could be beneficial to the workers at home in the imperialist country, as well as for those in the colonized countries. Yet, there was still a little ways further to go if anarchists were ever to complete the circle in matching Lenin’s particular revolutionary defeatist policy.

From Theory to Practice

Once we arrive at the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, things get dicier still. Kropotkin proclaimed that “every war is evil — whether it ends in victory or defeat.” He predicted that military defeat for the Russians would cause patriotism and chauvinism to “dominate the situation and cut short even purely political agitation.” A year later, he was discussing the Russian Revolution of 1905 and mentioning the mutinies of soldiers and sailors, such as those of the Battleship Potemkin, contradicting the prediction he’d just made.

Kropotkin at this point was still against imperialist war, but wasn’t any kind of revolutionary defeatist. Lenin wasn’t yet a revolutionary defeatist either and instead openly sided with the Japanese imperialists rather than with the anti-war Japanese socialists, as Kropotkin did.

“Advancing, progressive Asia has dealt backward and reactionary Europe an irreparable blow,” Lenin claimed, failing to consider the brutal occupation of East Asia and the alliance with European fascism that the Japanese Empire would go on to perpetrate. Lenin, at this point, wished for the defeat of his own government, Russia, but not the defeat of all imperialist governments, and failed to take into account the perspectives of revolutionaries within Japan and the East Asian victims of Japanese imperialism.

Now we can outline three different positions. With the first, a revolutionary could be reductively anti-war and equally against all sides, like early Kropotkin and later Trotsky, dismissing the benefit of military defeats for the workers of each imperialist country and the people of the colonies. With the second, a revolutionary could be one-sidedly defeatist, like the early Malatesta and Lenin, only seeing the benefit of defeat from the perspective of one side of an imperialist conflict (Britain and Russia but not the Boers and Japan). With the third, a revolutionary could wish for the defeat of all the imperialist countries and for revolutionaries in each imperialist country to take advantage of the situation, like the later Lenin and Zinoviev.

Additionally, one could see a national liberation struggle as just, as the early Malatesta and Kropotkin did with the Greeks of Crete, and yet still be opposed to both imperialist military intervention and anarchist intervention that would concede ground to militarism and statism by submitting to the methods of national combatants and their imperialist backers (as some anarchists do today with Ukraine).

One could also confuse opposition to invasion with the principle of self-determination, as the later Kropotkin did. For him, WWI meant France and Belgium had to be defended from German invasion, even if this meant a concession to the statism and militarism of the Allies. It wasn’t that Kropotkin was unaware of French and Belgian colonialism in Africa, it’s that he placed this as a secondary concern after the defence of his favoured European countries.

Kropotkin failed to consider that if one wanted to exalt resisting invasion as the ultimate anarchist principle, one would first have to go and take up arms in the colonies against France and Belgium before joining French and Belgian forces against German invasion.

Kropotkin was not upholding self-determination against Austro-German imperialism in WWI, he was upholding Belgian and French supremacy over Africa and the Pacific. This reminds us that today’s anarchist supporters of Ukrainian and NATO militarism don’t so much oppose invasion on principle as they uphold Ukrainian lives (even reduced to cannon fodder) as being more valuable than the lives of people oppressed and killed by NATO and Israeli imperialism all over the world.

In this limited sense, Kropotkin’s stance on the First World War can be compared to that of the arch-statist Joseph Stalin, who in the lead-up to the Second World War called for a united front against fascism, in defence of democracy. A democracy that Trinidadian socialist and anarchist fellow traveller George Padmore critically pointed out was something that colonized peoples “have never known.”

Conflict and Contradiction

Back in 1909, in response to Spain’s Second Melillan Campaign against Morocco, Barcelona’s workers rose up against a new mobilization of troops, taking the torch to bourgeois institutions across the city. This, and the brutal state repression that followed, including the execution of the anarchist educator Francisco Ferrer, proved a testing ground for the anarchist movement that would later oppose WWI and then rise up against the fascist military coup in 1936.

The Mexican-American Border War of 1910-1919 provided an immediately practical test for American anarchists and other social rebels. War or revolution? Support the social uprising right next door and oppose the intervention of their own state, or just sit on the porch and watch their revolutionary neighbours be slaughtered? Mexican anarchists called for the American workers in general to not give a cent for their government’s intervention and to be wary of the bold resistance to invasion that Mexicans would put up. While some American anarchists, such as Voltairine de Cleyre, worked from home, organizing and speaking out in support of the Mexican Revolution, others, along with non-anarchist members of the Industrial Workers of the World, actually crossed the border and took part in the struggle in person.

Kropotkin admonished those Italian-American anarchists who crossed the border to take part in the struggle, only to return home to America exceedingly bitter, having expected, according to Kropotkin, large scale battles and campaigns of a traditional military character, or urban clashes at the barricades. Instead, they had gotten lost in the midst of a guerrilla peasant movement that they couldn’t understand. Despite their anti-militarism, the Italian-American anarchists were confusing war and revolution, just as Kropotkin himself soon would, once the Great War broke out.

Not addressed by Kropotkin was the fact that the Italian-American anarchists and their French comrade E. Rist, like the statist socialist Friedrich Engels, also thought that the mestizo and Indigenous peoples of Mexico were too backwards to be capable of social revolution. The Italian-Americans bristled at the suggestion that their French comrade Jean Grave could be wrong in his claim that the Mexican Revolution was only imaginary.

Ironically, only a few years later, Grave would join Kropotkin in supporting French and Belgian colonialism come WWI, causing the Italian-Americans to concede that their French comrades, as well as Kropotkin, were in fact capable of getting things wrong. Whether they learned from their own racist foolishness appears doubtful, just as today’s Euro-American anarchists also continue to wallow in anti-Native behaviour.

The Mexican-American anarchist print journal Regeneración was particularly strong in its opposition to WWI, and its editors paid the price for it, in the case of Ricardo Flores Magón, the ultimate price, the ending of his life within the walls of Leavenworth prison in Kansas.

In 1917, Magón had drawn inspiration from the multi-racial Green Corn Rebellion against conscription in Oklahoma. “The slogan of the revolutionaries is this: the present war is waged for the benefit of the rich,” he explained, “let us fight to the death here, rather than die in the European trenches.”

Anarchist Foreign Policy

Returning to Malatesta, we see that if he’d been deeply confused about the Boers, he also continued to be unequivocally opposed to militarism and imperialism as the years dragged on.

“For us, it is truly the very existence of the army that we want to destroy, however it is organized,” he explained in 1902, “it is loathing for the role of soldier — the role of slave and cop combined — that we must inspire in the spirit of the people and especially of the youth.”

A decade later, Malatesta was proclaiming that “now that today’s Italy invades another country and [King] Victor Emmanuel’s infamous gallows are being erected and put to work in the marketplace in Tripoli [in Libya], it is the Arabs’ revolt against the Italian tyrant that is noble and holy.”

“For the sake of Italy’s honor,” he wrote, “we hope that the Italian people, having come to its senses, will force a withdrawal from Africa upon its government: if not, we hope that the Arabs may succeed in driving it out.”

Two years following, just months before the Great War for colonies started, Malatesta further clarified what an anarchist foreign policy should be. Anarchists are against the partition of the world into states. They want the full and free fraternization of all peoples regardless of ethnicity and language but also the “full autonomy of all individuals and of all groups.”

Nonetheless, as subjects of the government of Italy, anarchists in Italy were more affected and oppressed by their own government than by the government of, say, Japan, “and we in turn can do against the government of Italy what we would not have the means to do against the government of a distant country.”

“So the conclusion is that, for an anarchist, the primary enemy is the oppressor who is closest to him, and against whom he can fight more effectively,” Malatesta proclaimed.

We should highlight here that “primary” enemy does not mean “only” enemy, and that this article was published by Malatesta a full year before the infamous leaflet, ‘The Main Enemy Is At Home!’, by the German socialist Karl Liebknecht, making this yet another example of anarchists beating their fellow socialists to the punch but not getting the credit they’re due, even from today’s anarchists.

Malatesta on the Great War

Once WWI erupted, Malatesta was bitterly opposed to Kropotkin’s change of colours, penning several articles criticizing him and his pro-war camp. Kropotkin was among the “comrades whom we love and respect most,” Malatesta wrote in an article in Freedom in November of 1914, but this would not protect him from criticism.

Malatesta was no pacifist. The question wasn’t whether to fight or not. But Kropotkin and some of his followers were associating themselves with the “governments and the bourgeoisie of their respective countries, forgetting Socialism, the class struggle, international fraternity, and the rest,” and that was the problem.

Echoing his old comrade Bakunin, Malatesta advised that anarchists should always be “on the look-out for an opportunity to get rid of the oppressors inside the country, as well as of those coming from outside.”

It was not a matter of welcoming invasions, it was not even a matter of always prioritizing the class struggle above all else, but class collaboration in the midst of active oppression was not something anarchists should engage in, Malatesta reminded us. Anarchists should, at the very least, “refuse any voluntary help to the cause of the enemy, and stand aside to save at least their principles — which means to save the future.”

Malatesta clarified that as bad as the “mad dog” of Berlin and the “old hangman” of Vienna may be, he had no greater confidence in the Russian Tsar, nor the English who were oppressing India, nor the French who massacred Moroccans, nor the Belgians who committed atrocities in the Congo.

The victory of Germany would certainly increase militarism, but the victory of the Allies would augment it too, and would maintain Russian and British domination in Asia as well as Europe. In Malatesta’s view, it wasn’t just a question of victory or defeat, it was “most probable that there will be no definite victory on either side,” both sides could end up exhausted, patch together some kind of peace, but leave things unsettled, “thus preparing for a new war more murderous than the present.” How right he was!

“The only hope is revolution,” Malatesta wrote, “and as I think that it is from vanquished Germany that in all probability, owing to the present state of things, the revolution would break out, it is for this reason — and for this reason only — that I wish the defeat of Germany.”

He admitted that his predictions might not be correct, but what was really fundamental was for all socialists, including anarchists, “to keep outside every kind of compromise with the Governments and the governing classes, so as to be able to profit by any opportunity that may present itself, and, in any case, to be able to restart and continue our revolutionary preparations and propaganda.”

None other than the socialist going fascist figurehead Benito Mussolini pounced on Malatesta for this position. If Malatesta wanted Germany’s defeat, why didn’t he actively work toward this end in a traditional interventionist and militarist manner? Malatesta responded in an open letter in his anarchist print journal Volontà, explaining that actually working toward certain ends was only beneficial if the material and moral cost of doing so was less than its benefit.

Events can either work in favour or against our ends. In every case, we have a choice to make and do not have to abandon our own path in order to promote what we consider to be indirectly useful for us. Police brutality can sometimes provoke an uprising, Malatesta pointed out, but only if the public mind is predisposed to it.

From his point we can extrapolate further that although anarchists wish for anti-police uprisings, it would not make sense for anarchists to work to increase police brutality in hopes of a retaliatory insurrection. It’s neither logical nor useful for anarchists to support capitalism and the State as part of their struggle for anarchistic ends.

Malatesta, for his part, also admitted that the German socialists, in trying to save European civilization from Russia, had put themselves at the service of their own government’s despotism, lessening the chance of revolution in Germany. Italians should stay out of the war, any military conscription would be repugnant, and if one called for it, one couldn’t speak out of the other side of one’s mouth about anti-militarism. This is a lesson that the modern-day Russian anarchist Dmitry Petrov still hadn’t learned when he supported Ukrainian conscription in an interview with a German media outlet in 2023.

In all of this, we see that Malatesta still wasn’t exactly a revolutionary defeatist in the style of Lenin, even if he came fairly close to it, and in some ways preceded Lenin’s analysis. In his open response to Mussolini, Malatesta speculated that the defeat of Britain or France in WWI, given the social conditions of the time, could increase patriotism and serve the interests of reactionaries in those countries. Malatesta was not a determinist in the style of Lenin or Kropotkin.

One couldn’t always say in advance exactly how things would turn out, whether military defeat would create beneficial conditions for revolution within the imperialist countries or not. Defeat could be beneficial in one case but not in another, within the same inter-imperialist war. What one could always do, however, was maintain their revolutionary principles and practice, so that there would still be a future to fight for, instead of a future gambled-off in hopes of an ill-gotten pay day. The main enemy, whether local, invader or both, was still at home.

Assessing the Aftermath

The Second World War proved the anti-war anarchists right and the Kropotkin camp wrong. The First World War, the supposed “War That Will End War”, didn’t do the job.

Colonialism continued in the lead up to WWII, as European anarchists criticized the British occupation in Palestine and the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. Anarchists in Spain rose up against the fascist military coup in 1936, only to be betrayed by the world, when they weren’t busy betraying themselves. Some tried and failed to link Moroccan autonomy to the struggle.

Once WWII started, the English anarchists of War Commentary and their Jewish American contributor Marcus Graham criticized all sides of the conflict and pointed out that the European and American democracies had been materially and politically supporting all the Axis powers in the lead up to the cataclysm. For these anarchists, militarism still wasn’t the solution to militarism, and imperialism still wasn’t the solution to imperialism.

Upon the end of WWII, War Commentary and Graham were also proven right, as British imperialism continued to crush Asia and Africa, and the State of Israel was born upon the genocide of the Palestinian people, a catastrophe that continues to this day. France did not free Kanaky. It heightened its brutal colonization of Algeria and Vietnam. America leveled entire Japanese cities with nuclear bombs, massacring Japanese and Korean civilians. It proceeded to go to war directly against Korea and Vietnam and via proxies against Central and South America. The Allies had fought the fascists, but they’d done so for the freedom to oppress. Both world wars had been wars for colonies. The colonized could not rely on any Western saviours. They could only free themselves.

The world of the Cold War was not only split into the two camps led by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the United States of America, but also the third camp of the Non-Aligned Movement, which was launched by Yugoslavia, India, Ghana, Indonesia and the United Arab Republic (Egypt and Syria). Yet even in this case, Indonesia invaded and occupied West Papua and then East Timor. Self-determination was continuously made into a sham by the states of the three major camps and beyond. Nevertheless, the anti-colonial resistance continued, with revolts in Africa even contributing to an uprising in Portugal in 1974. The Palestinian struggle continues today, under the harshest possible conditions.

Back to the Present

Anarchists today find themselves lost, muddled and ignorant of their own history. They seem to have little to no knowledge, let alone understanding of Bakunin’s call for civil war against invasion, nor of Malatesta’s stance that the main enemy is at home, nor of his insistence that for the people of an imperialist country, military victory could be worse than defeat.

Just as the world of the Cold War was not really a simple binary, neither does today’s anarchist analysis of war need to fall into crude binaristic thinking. It’s not the case that there are only two options; that if one is to support national liberation and be against invasion, one has to put aside anti-militarism; or that if one is to be anti-militarist and internationalist, one has to put aside national liberation and resistance to invasion.

As the Spanish anarchist print journal Solidaridad Obrera put it in 1936, “Our internationalist thinking, one hundred percent, induces us to pose the problem of the colonies.”

As Bakunin and Malatesta argued, in the case of war among imperialist states, one should resist invasion by way of civil war, neither through pacifism nor by means of militarism.

As Fredy Perlman explained from personal experience, and the ongoing ethnic cleansing in Palestine reminds us, being oppressed can lead one to become an oppressor rather than a social revolutionary. Statist methods can’t solve the problem of imperialism.

The historical anarchists, despite their steadfast anti-militarism and anti-imperialism, which was more coherent than that of the statist socialists, still never quite became revolutionary defeatists, and never fully investigated settler colonialism.

The potential remains, however, for today’s generation to recover the anarchist anti-imperialist and anti-militarist tradition, and at the same time update and improve upon it for our current conditions. Today’s anarchists, if they so choose, can better educate themselves about the character of settler colonialism, imperialism and militarism, and can outline the necessity and practicality of opposing the main enemy at home, as well as all oppressors everywhere. Whether anyone actually takes up this task and still seriously considers their freedom and their oppression to be tied up in that of other people’s remains to be seen.

* * * * * * * *

Notes

1. Engels, in an 1847 speech about Poland had said, “a nation cannot be free and at the same time continue to oppress other nations.” In a screed against Bakunin, only two years later, Engels was writing that “lazy Mexicans” couldn’t do anything useful with their country, so it was good that America, still a slaver country at the time, had expanded its empire into the territory of Mexico, a country that had abolished slavery already by 1829, before Britain, America and Germany would.

2. Lenin, in a Sotsial Demokrat article published in November 1914, wrote, “in the present situation, it is impossible to determine, from the standpoint of the international proletariat, the defeat of which of the two groups of belligerent nations would be the lesser evil for socialism. But to us Russian Social Democrats there cannot be the slightest doubt that, from the standpoint of the working class and of the toiling masses of all the nations of Russia, the defeat of the tsarist monarchy, the most reactionary and barbarous of governments, which is oppressing the largest number of nations and the greatest mass of the population of Europe and Asia, would be the lesser evil.”

This, however, cannot be considered his first public declaration of revolutionary defeatism because it explicitly limits the matter of defeat to Russia rather than all imperialist countries.

References, sources and resources

The Struggle for Kanaky, by Susanna Ounei-Small (1995)

Socialism and War, by V. I. Lenin and G. Y. Zinoviev (1915)

The Right of Nations to Self-Determination, by V. I. Lenin (1914)

Man, Society, and Freedom, by Mikhail Bakunin (1871)

Statism and Anarchy, by Mikhail Bakunin (1873)

The Defeat of One’s Own Government in the Imperialist War, by V. I. Lenin (1915)

Ukraine’s [Israeli] Tavors, by The Armourer’s Bench (2022)

Pentagon Sends U.S. Arms Stored in Israel to Ukraine, by the NY Times (2023)

How [Israel’s] RGW 90 (Matador) is Helping Ukraine’s War Effort?, by Interesting Engineering (2023)

U.S. to send Israel artillery shells initially destined for Ukraine, by Axios (2023)

The Myth of Lenin’s “Revolutionary Defeatism”, by Hal Draper (1953-54)

Revolutionary Defeatism: The Old Bolsheviks and the ‘Great War’, by Dave Harker (2022)

The Practical Policy of Revolutionary Defeatism, by Matthew Strupp (2020)

The Russian Battleship Potemkin Mutiny of 1905, from Wikipedia

The Kiel Mutiny of 1918, from Wikipedia

Let Us Make War Against War, by Leonard D. Abbott (1914)

International Anarchist Manifesto on the War (1915)

Tierra y Libertad, November 25 (1914)

Resolutions on the Imperialist War, by the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (1914)

International Socialist Conference at Zimmerwald Manifesto (1915)

Letters to a Frenchman on the Present Crisis, by Mikhail Bakunin (1870)

Tierra y Libertad, November 4 (1914)

The Conscripts Strike, by Louise Michel (1881)

For Candia, by Errico Malatesta (1897)

Ukraine’s nuclear deal with Canada’s Cameco carries big risks, rewards, by Reuters (2023)

The Ukrainian refugee crisis of 2022-, from Wikipedia

Trailer for ‘Sir! No Sir!’ (2005)

The Effect of War on the Workers, by Emma Goldman (1900)

Living My Life, Chapter 18, by Emma Goldman (1931)

The Complete Works of Malatesta, Vol. V, edited by David Turcato (2023)

A Poetics of Anticolonialism, by Robin D.G. Kelley (1999)

The Russo-Japanese War, by Peter Kropotkin (1904)

Imperialism: Monster of the Twentieth Century, by Shūsui Kōtoku (1901)

The Revolution in Russia, by Peter Kropotkin (1905)

The Fall of Port Arthur, by V. I. Lenin (1905)

Hands off the Colonies!, by George Padmore (1938)

The Tragic Week in Catalonia, from Freedom (1909)

People of America, by Ricardo Flores Magón (1911)

Will this Struggle be Drowned in Blood?, by Voltairine de Cleyre (1911)

Report of the Work of the Chicago Mexican Liberal Defense League, by Voltairine de Cleyre (1912)

Reds Die For Freedom, by the Industrial Workers of the World (1911)

A Debate on the Mexican Revolution in Temps Nouveaux (1912)

Murderous Silence: Luigi Galleani and Cronaca Sovversiva, from Regeneración Sezione Italiana (1911)

The Seattle Anarchists Go to Mexico, edited by The Transmetropolitan Review (2024)

Against War, Against Peace, For The Social Revolution, by Luigi Galleani (1914-15)

The Barricade and the Trench, by Ricardo Flores Magón (1915)

On the March, by Ricardo Flores Magón (1917)

The Green Corn Rebellion of 1917, from Wikipedia

“The Armed Nation”, by Errico Malatesta (1902)

The War and the Anarchists, by Errico Malatesta (1912)

Our Foreign Policy, by Errico Malatesta (1914)

The Main Enemy Is At Home!, by Karl Liebknecht (1915)

Anarchists Have Forgotten Their Principles, by Errico Malatesta (1914)

Lettre à Musolini, par Errico Malatesta (1914)

Russischer Anarchist verteidigt Ukraine, von Taz (2023)

The War That Will End War of 1914-1918, from Wikipedia

Bloodied Palestine, by Camillo Berneri (1929)

What Can We Do?, by Camillo Berneri (1936)

This Is Not A War For Freedom!, by War Commentary (1939)

The Axis Versus “Democracy”, by Marie Louise Berneri and John Hewetson (1941)

What Made Fascism Possible?, by Marcus Graham (1943)

Mankind and the State, by Marcus Graham (1946)

British Army of Oppression Crushes Eastern Freedom, by Marie Louise Berneri (1945)

British Intervention in Asia, by Marie Louise Berneri (1945)

Malaya, by Albert Meltzer (1948)

The Non-Aligned Movement of 1961-, from Wikipedia

Anarchy in Indonesia and the Guerrilla Struggle in West Papua: An Interview (2018)

Indonesian Invasion of East Timor of 1975, from Wikipedia

The Portuguese Colonial War of 1961-74, from Wikipedia

The Carnation Revolution of 1974, from Wikipedia

The Palestinian Struggle Continues, from Insurrection (1988)

The Right of Peoples to Determine Themselves, by Solidaridad Obrera (1936)

Anti-Semitism and the Beirut Pogrom, by Fredy Perlman (1983)

Three Genocides, by Eyal Weizman (2024)

The Class Nature of Israeli Society, by Haim Hanegbi, Moshé Machover and Akiva Orr (1971)

Anarchism and the First World War, by Matthew S. Adams (2019)

Anarchist Opposition to Japanese Militarism: 1926-1937, by John Crump (1991)

Also

Anarchists & Fellow Travellers on Palestine

Anarchists on National Liberation