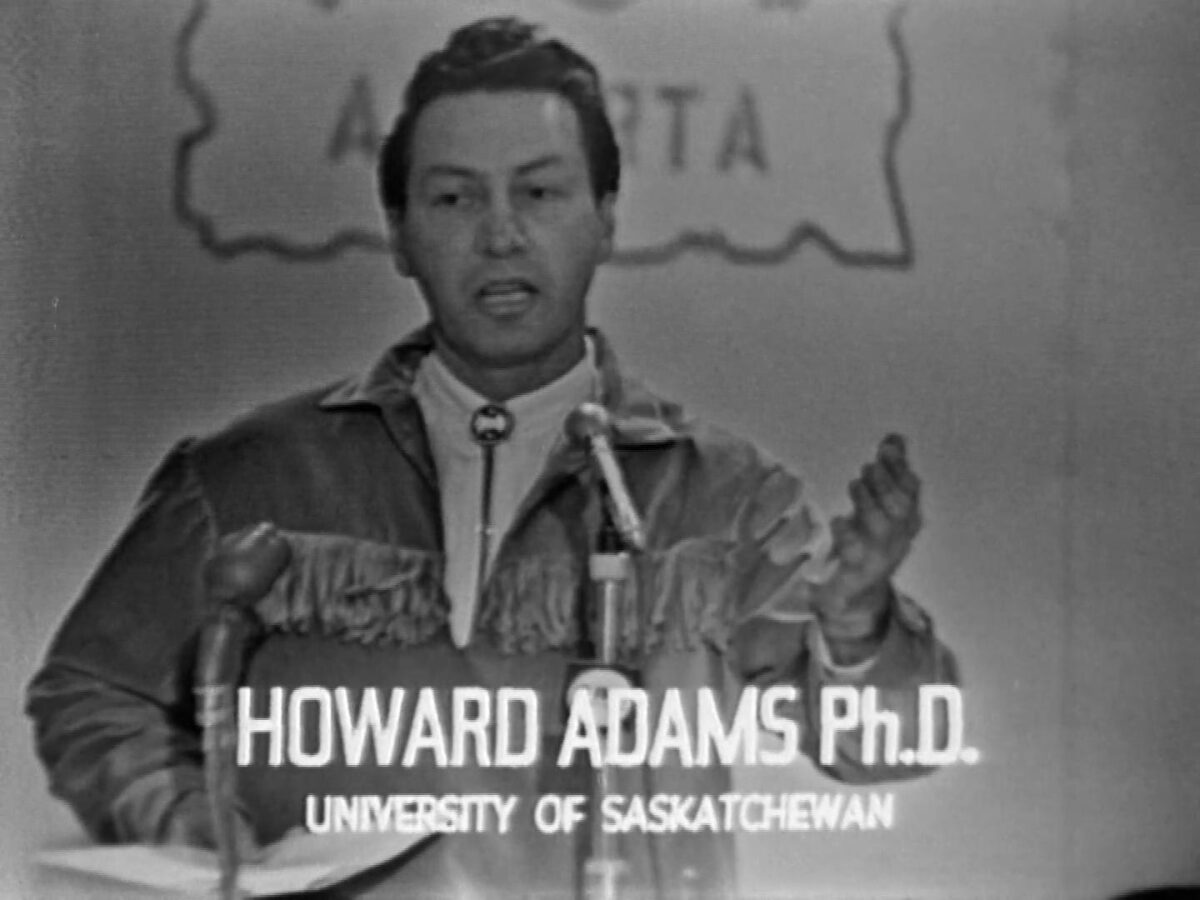

From ‘Native Movement’, 1970, xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) territory, Vancouver, BC

The following article was submitted by Brother Howard Adams, former president of the Metis Association of Saskatchewan. It was edited by the Native Movement editorial committee.

A new breed of native organizations have sprung up across Canada in the last few years. They have become active, and politically powerful in the native world. They are financed entirely by the provincial and federal governments with grants in some cases exceeding half a million dollars. Consequently, they are tied closely to the governments: because, where money goes — goes control. In actuality, some of these organizations have become extensions of the government, or a new Native Department, with Native officials administering the programs. Many programs are the same earlier ones, but with a new Indian emphasis.

One of their major contributions is in public relations; they have brought to the attention of the Canadian public, the serious plight of our brothers and sisters. In turn, this created a national concern. However, their activities are restricted to the government’s decisions and approval.

These organizations are the outgrowth of the recent native awakening in Canada. As we began to raise our voices in discontent, and attract the attention of the news media, the government began to worry. They did not want a situation in Canada similar to that of the Black Power movement in the United States. The government looked around for organizations and leaders to serve as a new type of native administration. They wanted to give the natives a voice in running their affairs, without giving power to the masses. By putting native persons in charge of the organizations and programs, it would look like a step forward, and an effort to answer the demands of the Indians.

We can be sure governments did not suddenly become interested in the welfare of the natives. They were interested in saving their political positions and their social order. Some of our brothers and sisters have become critical of these organizations, and have labelled them as the new colonial regime, or the new Indian Affairs Branch. There could be some truth in this statement. If the organizations are allowed to operate unchecked, without being responsible and responsive to the people, then the criticism is justified. At the present time they are responsible to the governments.

They cannot do anything that would embarrass or endanger the governments. Also, they are organized exactly along the lines of Whiteman’s organizations. The leader is usually a chief or a president, with lesser officials below, and a crew of bureaucrats. Presently, their main function is to administer programs that are decided upon by the organization officials and government authorities.

These programs are not coming from the grass-roots people. We should be suspicious when governments start putting large sums of money into native organizations. Governments of the past have not always been honest with our people, and they are not likely to suddenly change now. There is an old story that says, “Nobody can handle slaves better, and make them work better than another slave.” We must watch the whiteman and see that he does not develop a “house Indian” for handling the “field Indians”.

Institutional Racism – Howard Adams (1988)

Howard Adams at Indian Culture Days at the University of California-Davis, 1980 (Photo: Hartmut Lutz)

An excerpt from Howard Adams’ article in the book of collected texts, ‘Racial Oppression in Canada’, 1988

The study of institutional racism is a relatively new approach to the analysis of colonization in western societies. The emphasis of racial studies by social scientists has focused on the pathologies of Indigenous minorities, and possible solutions for their adjustment to the white middle-class society. However, from another perspective, it is possible to analyze institutional racism of white supremacy societies.

Institutional racism includes an ideology of one group proclaiming racial superiority over another group that is subordinated in the society. The differential access to power, privilege, and prestige by the dominant group, as well as the structure of economic, political, and educational inequality, are basic features of institutional racism. It is laws, customs, regulations, and practices that are racist, regardless of the personalities in power. Individuals living in a white supremacy society are often unaware of their discrimination. This lack of awareness makes their prejudiced behaviour less amenable to reform.

Institutional racism is a subtle and disguised process operating in established and respected bureaucracies of the society. These common offices, i.e. manpower, immigration, etc., contain structural factors of racism which are largely invisible and oblique, but nevertheless result in unjust treatment of Native people. The essence and ethos of bureaucratic organization in western societies is white superiority. Since racism pervades the policies and regulations of some institutions at the time of their creation, they will persist throughout the lifetime of such institutions.

The Indian Affairs Bureau exemplifies an institution that prestructures and predetermines Native people’s participatory relationship. Racial minority members who are powerless and outsiders have no alternative but conformity and submission to the operating norms of the institution. Even if certain discriminatory policies are modified, i.e. changing college admission criteria for minorities, inequalities in other parts of the institution will sustain racism, i.e. low quality of ghetto schools. Once racialist policies have been institutionalized, the role of the prejudiced person is either of little importance or plays a minor role because the operating bureaucratic policies and regulations function naturally in discriminating against Native persons. In other words, a white person acting in his/her official capacity is also victimized by the racism of the institution.

Institutional racism is a system of policies and regulations that perpetuates inequality by the state. It is interrelated and reinforced across organizational and bureaucratic sectors. The consequences are the primary indicators of institutional racism. For instance, in Saskatchewan the prison population is comprised of approximately 50% Native males and nearly 90% Native females. Yet, Indians and Halfbreeds constitute only 8% of the total population.

A white supremacy society is not maintained exclusively by prejudicial attitudes of individuals, such as judges, policemen, and teachers, but by the institutionalization of inequality. It can operate independently of individual prejudice. On the other hand, it is possible for institutional racism to be reduced to personal attitudes because white officials eventually surrender to the doctrine of the institution, thus responding to coloured persons in a prejudicial manner.

Yet there remains an ambiguity between personal and institutional racism because of the uncertainty of the boundaries. It is not always easy to state whether discrimination is strictly personal bigotry or the consequences of institutional racism. Prejudice may be both subjective and objective at the same time. It is subjective when a response demonstrates the personal prejudices of an individual and objective when the response shows the institutionalized acts of inequality located in the hierarchies of bureaucracy.

The manifestations of inequality will vary along such lines as the degree of emotional intensity, extent of effect on the minority groups and the degree of visibility of the discriminatory act at the time. Institutional racism is less difficult to prove than personal prejudice, because the former can be measured in objective terms, such as ghetto schools, minority slums, infant mortality rates, school drop-outs of minorities, etc. Another instrument of measurement of institutional racism is “credentialism,” meaning degrees in medicine, law, teaching, etc.

One of the early establishments of institutional racism in Canada was the church, particularly the Roman Catholic church which initiated vigorous efforts to “civilize the heathen savages”. This was the forerunner to a succession of similar state institutions that served the interests of a white supremacy society. These racial institutions continued to develop over a period of many decades.

Canadian society specifically had never been put to a serious test regarding its institutional racism until 1969 when the Black students at Sir George Williams University occupied the computer centre. Analyzing the situation two years later, one of the students concluded that the problem “…is to be found in the racist nature of the country and all its institutions” (Forsythe, 1971: 114). Since almost all the students involved in this experience were Blacks from the West Indies, it became a racist confrontation. In their struggle with Canadian law, the Black students soon realized that they were dealing with a racist court in its judicial capacity as an oppressive mechanism.

In referring to the Canadian government and political figures, Forsythe states that “the same racist tendency to prejudge on the basis of colour was evident here…” (Forsythe: 132). Forsythe further claimed that “it should be stated… that this type of reaction is hardly sufficient to offset the stark realization by the minority of black people that Canada is indeed racist” (Forsythe: 139).

Excerpt from Howard Adams’ speech at a sociology and anthropology conference in Banff in 1969

…Just one word about the business of racism in Canada, I have said this many times before, and I think it is because I see the institutions of Canada so deeply entrenched and so effective in the socialization process of the Canadians.

The Canadians are the most arrogant and the most self-righteous people in the world. They are the people who are always so willing to offer their services to the United Nations for the troubled spots of the world, to go and solve the racial conflict or any kind or turmoil between groups of people – not recognizing that they themselves are the most racist-minded people in the whole world.

And I might say that in the parts of the world that I have traveled in – they have not been that extensive but have been reasonably extensive – I have found that the people know Canadians are racists. We are the only people who really don’t know. We are fooling ourselves into believing this. No, we are just kidding ourselves, wanting to give ourselves a very nice feeling about the fact that all the racism is in the terrible part of the United States, in the southern part, and in Africa…

Also

Native Alliance for Red Power – Eight Point Program (1969)

Capitalism, the Final Stage of Exploitation, by Lee Carter (1970)

The Need for a Revolutionary Struggle, by Howard Adams (1972)

The Other Side of the Ledger: An Indian View of the Hudson’s Bay Company (1972)

The Form of the Struggle For Liberation, by Howard Adams (1975)

‘Marxism and Native Americans’, reviewed by Howard Adams (1984)

No Surrender – Howard Adams on the Oka Crisis (1990)

Thoughts on the Constitution and Aboriginal Self-Government, by Howard Adams (1992)

Overshadowed National Liberation Wars, by Howard Adams (1992)

The Lost Days of Columbus, by Lee Maracle (1992)

Challenge to Colonized Culture, by Howard Adams (1995)

“70: Remembering a Revolution” in Trinidad and Tobago, by Paul Hébert (2016)

Regina’s radical university students hosted the Black Panthers in 1969, by Ashley Martin (2016)

Selling the Sixties Scoop: Saskatchewan’s Adopt Indian and Métis Project, by Allyson Stevenson (2017)