From ‘ABC: Americans Before Columbus’, 1964

Past issues of ABC have related the essence of the steady attack against Indian fishing and treaty rights in Washington State.

Armed with new court decisions and laws of their own making, of the supreme court and legislature, the state had stepped up its efforts to completely abrogate Indian treaty rights.

Tribes Face Odds

The tribes have faced tremendous odds in this ceaseless battle. In addition to the machinery of state government, the news media had been attempting to write the Indians’ obituary daily.

Past years have seen the newspapers filled with the propaganda of the State’s Department of Game and Fisheries in their effort to brand the Indians as deflators of the salmon runs.

Guided by so-called sports fishermen groups — who have pressured the state, the press, and the politicians with fierce demanding — the drive to completely halt Indian fishing moved closer to success.

And the Indian people? What was our strategy? How were we meeting the threats to our families’ livelihood? Threats to our existence as Indian people?

For the most part, no strategy existed.

At best, individual tribes established their own lines of defense for their own tribe only.

Usually, however, a defense was made only by individual Indians who had been challenged directly by arrest or general harassment.

No Defense Made

Frequently, unfortunately, no defense was made — the consequence being that entire rivers were surrendered, in some cases, and entire tribes withdrew from their aboriginally-derived and treaty-protected fishing grounds.

In some sense, the lack of Indian action was understandable.

Many of the smaller tribes derive their only income from taxes on the fishery resource. And the livelihood of many Indian families are wholly dependent upon fishing income.

Therefore, a number of small tribes just could not afford to defend their rights or uncertain of their rights, not sure that it would be worth it — neither could they secure the aid of other larger tribes, nor adequate voluntary legal aid.

But the saddest situation involved those tribes who thought, and think they would not be seen, that their lands and fisheries would be overlooked, if they jumped on the state-sports-fishermen bandwagon.

Actually, these tribes practiced concession for themselves and betrayal of other tribes — actually supporting nothing or no one.

Makah Are Exception

The Makah Tribe, plus a few others, stood as an exception to these general descriptions. This tribe was concerned with every threat, every infringement upon Indian rights, regardless of the tribes directly involved.

It was their victory in reasserting their rights on the Hoko River — in a court case spanning the 1930’s [to ’50s] — that had again asserted all tribes’ rights for full utilization of their off-reservation usual-and-accustomed fisheries. For many tribes, these are the most important fisheries; for some tribes, the only fisheries.

Therefore, every state success was erasing the earlier court victories of the Makahs and other tribes.

Years-decades-centuries of ceaseless battle and protection of their rights — their way of life and living — has not lessened the Makah’s determination to continue fighting as long as necessary.

In January, their tribal council committed themselves to renewed action.

Their tribal chairman, Quentin Markishtum, realizing the magnitude of the battle, depicted the spirit of his tribe and the coming campaign in his statement, “We are going to fight this to the end! If we can’t get the support of the other tribes — then, we’ll fight it alone!”

The Makah Tribe, then requested the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC), as represented by Executive Secretary Bruce Wilkie and Hank Adams, to lend whatever assistance possible to further the Indian cause, and to protect the Indian rights.

Immediately, NIYC and the Makahs began mapping plans and strategy for the campaign.

Every tribal council in the state was contacted, and a meeting scheduled for February 15, in Seattle, Washington.

The response was overwhelming — the results historic! From more than fifty tribes in the state, representatives from forty-seven attended the meeting Marceline Kevis, NCAI Area Vice President represented the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI).

Also represented were the Washington State Indian Council Inc., the Northwest Affiliated Tribes, the Inter-Tribal Council of Western Washington, and the National Indian Youth Council.

Each tribe gave general and detailed accounts of the attacks and encroachments upon their rights and lives.

A press conference was arranged — the first one conducted at a meeting of Washington State Tribes.

Covered by three network stations, and major newspapers, a large portion of the public began hearing the Indian viewpoints and arguments for the first time.

Council Gives Aid

The results of the meeting were heartening to the Indian people throughout the state. Forty-seven tribes had pledged themselves to a unified fight against loss of rights retained by them in treaties with the United States.

As a part of the joint effort, it was decided that a “Campaign of Public Awareness” would be undertaken. The mechanics of this campaign were delegated to the Makah Tribe and the NIYC to determine.

The NIYC agreed to handle public relations and publicity, and to help coordinate activities and arrangements of the campaign. Various details, information, and facts were released at a press conference on February 24, 1964. The following position statement was included:

“At 11 A.M., March 3rd, delegates from Indian tribes throughout the state will meet with Governor Rosellini in Olympia.

We will present him with a proclamation of protest regarding the violations of our treaties and other agreements with the United States.

Indians from throughout the state shall attend the presentation.

The presentation will be conducted in such a manner as to insure that the great pride and dignity of the Indian people shall be upheld.

Indians throughout the nation will conduct activities on their support for our endeavor.

A number of national Indian leaders shall be present in Olympia, as will a number of internationally known personalities who have become aware of the Indians’ situation in the State of Washington.

It is for the purpose of making our position known, and for dispelling widely-spread misinformation and prevalent misconceptions about our tribes and people that we have arranged this meeting with the Governor.

It is the fist major step in our ‘Campaign of Awareness.’ This program was initiated by the Indian Tribes of this state, and will be carried out by us in an united effort.

It will be conducted under the banner of truth.

We consider it highly unjust that our country’s duty and consequent power, to protect Indian treaty rights is too often measured only by our own expenses with complacency and indifference as a measure of the part played by our nation.

We have tried to resolve these differences through proper channels — winning cases in the higher courts, but losing in the lower ones.

We have depended heavily upon the ‘Good Faith’ of our nation, only to experience favorable federal court decisions falling upon deaf ears in state courts, when Indian treaties are at issue.

We can no longer bear the strain and burden imposed upon us by Broken Promises. We are keeping our part of the bargain. Now it is time for our country to uphold its end!

Our treaties with the United States were made in 1854, 1855, and 1856. No question about antiquity for them exists in the minds of the Indian people. These treaties were made with a view toward the future, and the spirit of the treaties is alive on the reservations today.

We must protest the utter disregard and unjust denial of rights retained in our treaties! These rights, that were exercised freely by our ancestors, are the mainstay of our livelihood today. They have been the essence of our survival since time immemorial.

However, it is with regard to the future that we believe it necessary to protect our treaties and preserve our rights.

As an investment in the future, Indian tribes have always been advocates and employers of conservation practices. To conserve our fish, we believe that we must first protect our streams and waterways.

We deplore the laxity of state agencies in not taking effective measure to control destructive, yet unnecessary pollution: to control improper logging and other commercial operations that clog or severely damage river beds; to protect the watersheds; to provide adequate passageways past dams; nor to regulate modern fishing equipment, such as electronic devices, which virtually allow entire schools of salmon to be caught.

In the pretense of conservation, however, the state is trampling on sovereign treaties!

It is ironic that the ‘original conservationists’ — who practiced conservation as a way of life, long before there existed a State of Washington, or its Dept. of Fisheries, or Dept. of Game — should be made the scapegoat of a few militant non-Indian citizens who misinform the public and, as a result, deprive a people of a livelihood!

We have no other choice now, but to take our problem directly to the Governor of the State of Washington, the citizens, and the nation!

We are confident that we have the best wishes of all citizens who believe in the ‘Good Faith’ of our nation, and will be joined by those who are able to do so, as we congregate at the State Capitol in protest of the violations of the Supreme Law of the Land.”

Meet with Governor

The initial arrangement for the meeting with the Governor had already been made, and his office has a clear understanding of its nature.

The tribal officials were meeting with Governor Rosellini as representatives of sovereign nations, no less than his equal.

It was the first time since the negotiation of the treaties with the United States that the tribes stood with such stature.

Although a protest meeting, it was also designed to be a major step in the Indians’ “Campaign of Awareness.” Therefore, a highly formalized and programmed schedule of Indian and non-Indian speakers was devised.

All Indian people in the state were invited for the purpose of showing a personalized vote of confidence in their leaders and support for the Indian position.

Realizing that a campaign of awareness can be successful only if conducted before the public eye, the public was invited also. These arrangements having been made, other plans for the “awareness campaign” were made.

NIYC President Mel Thom; Executive Board of Directors Clyde Warrior, Karen Rickard, Gerald Brown, John R. Winchester, and Shirley Witt; plus NIYC Executive Director Herb Blatchford arrived in Olympia to aid in the effort.

Marlon Brando was invited for the purpose of drawing national attention to the campaign, and for attracting closer coverage by the news media.

Other prominent Indians and non-Indians came from out-of-state to witness the event and to become informed about the issues.

In order to assert Indian fishing rights and to dramatize and draw national attention to the fishing issues, a series of fish-ins (as they were termed by the press) were conducted at the request of several Tribes.

On March 2, Marlon Brando, Bob Satiacum (Puyallup), and Canon John Yaryan of the Grace Cathedral Episcopal Church in San Francisco drifted the Puyallup River and caught two Steelhead — as scores of Indians cheered them from the bank, and many non-Indians looked on. Brando and Canon Yaryan were promptly arrested by the state, but later released without charge — in an obvious attempt to minimize national coverage and attention.

Another fish-in was conducted on Wednesday, March 4th, by members of the Quileute Tribe, Brando, and members of NIYC. No arrests were made on this occasion. However, at the same time on the Nisqually River, six Indian fishermen were arrested for fishing and sent to jail for thirty days for fishing in violation of a restricting order, and violating the terms of a suspension of sentence on contempt charges.

Present Issues

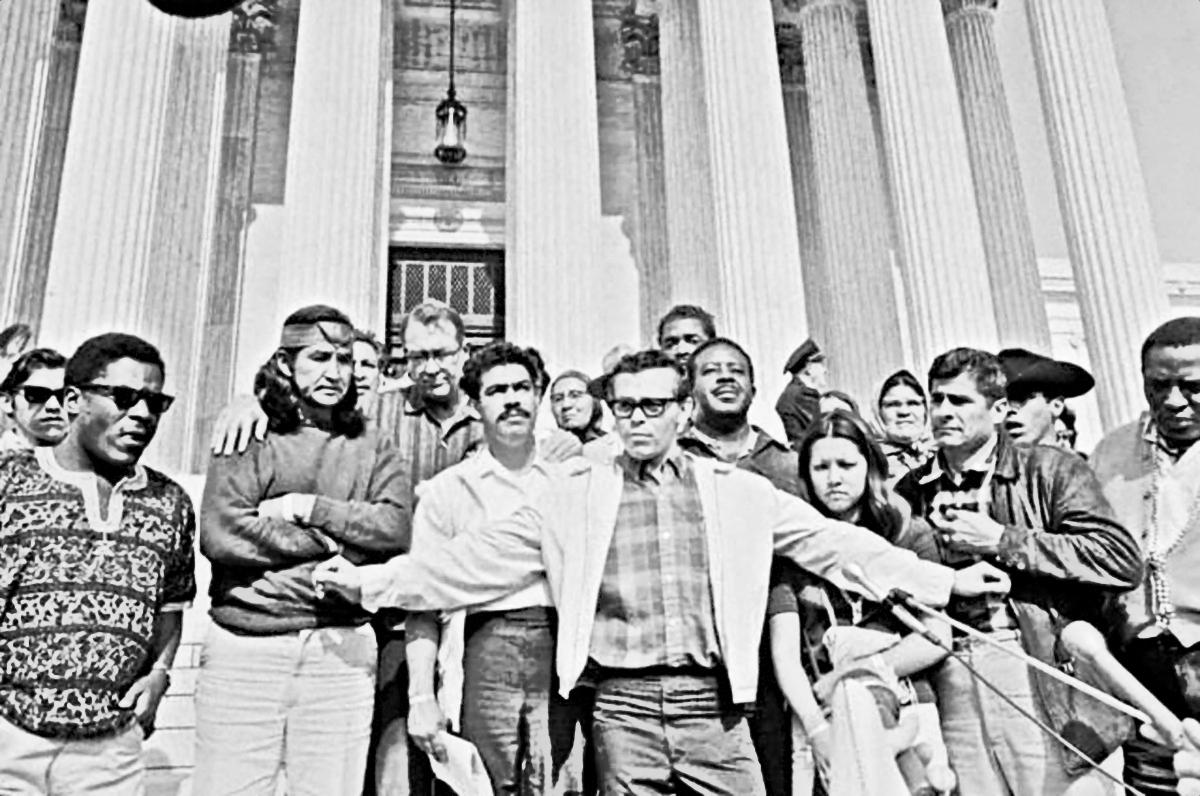

The mass protest meeting in Olympia was the major activity, however. With more than a thousand Indian people looking on and as many non-Indians, Indian spokesmen and our guests made a clear and impelling presentation of the Indian cause and issues.

Dancers and singers from the Makah and other tribes initiated the occasions with dances and songs emphasizing the Indians’ attachment and closeness to nature.

Prior to the meeting and afterwards, Governor Rosellini invited members of the NIYC, and the representatives of tribes to engage in discussion and consultation on the issues involved and other problems. Whereas, we had originally been allocated an hour in the Governor’s schedule because of his other commitments, we resulted in utilizing more than four and one-half hours to present our viewpoints.

What is significant is that we proposed a very positive and constructive approach to the solution of the various problems and issues with which we were involved.

Our proposals included a demand for a moratorium on the arrests of Indians fishing in their usual and accustomed fishing grounds; the initiation of a joint federal, state and Indian study of Washington rivers to determine actual causes of depletion, and for establishing a realistic program of salmon resource rejuvenation; the setting up of an Indian advisory board to the Governor; a program of public information on Indian problems; and the repeal of a 1953 legislative law which extended partial state jurisdiction over Indian reservations.

Governor Rosellini agreed to establish the advisory board, and promised that the sovereignty of tribes would be protected as long as he is in office — but for the most part, the demands were not met.

Also

Treaties with the Tribes of Washington State (1854-55), from UW Law

Decision, Tulee v. Washington (1942)

“Since about 1933 the defendant and his predecessors [the State of Washington] have, by arresting or threatening to arrest and by confiscating or threatening to confiscate fishing gear, prevented the Makahs from taking fish from the Hoko river.”

Makah Indian Tribe appellants’ opening brief (1951)

Decision, Makah Indian Tribe v. Schoettler, Director of the Department of Fisheries (1951)

Nisqually Proclamation or “Statement of Facts” (1965)

The Last Indian War, by Janet McCloud (1966)

We Are Not Free, by Clyde Warrior (1967)

I am a Yakima and Cherokee Indian, and a man, by Sid Mills (1968)

Is the Trend Changing?, by Laura McCloud (1969)

Viewpoint of People Living on Puyallup River, by Ramona Bennett (1970)

Richard Oakes, Alcatraz and More, by Hank Adams (1972)

Trail of Broken Treaties 20-Point Position Paper (1972)

United States v. Washington, Boldt Decision (1975), from Wikipedia

Proclamation of the Puyallup Tribe on the Repossession of the Cushman Indian Hospital Lands (1976)

The Brave-Hearted Women: The Struggle at Wounded Knee, by Shirley Hill Witt (1976)

Taking Back Fort Lawton, by Bernie Whitebear (1994)

Sovereignty, by Monica Charles (2005)

The Fish-in Protests at Franks Landing, by Gabriel Chrisman (2008)

The Carver’s [John T. Williams’] Life, by Neal Thompson (2011)

Ramona Bennett Receives 2018 Bernie Whitebear Award, by Frank Hopper (2018)

Leonard Peltier’s Statement for Ramona Bennett (2018)

Henry “Hank” Lyle Adams Obituary, by Northwest Treaty Tribes (2020)

The Day the Indians Took Over Seattle’s Fort Lawton—and Won Land Back, by Frank Hopper (2023)

Fighting for the Puyallup Tribe: A Memoir, by Ramona Bennett Bill (2025)

ICE looks to WA tribes to house detained immigrant, by Nina Shapiro (2025)